полная версия

полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Times, May 9, 1803: “On Sunday afternoon two gallies, each having an officer and press-gang in it, in endeavouring to impress some persons at Hungerford Stairs, were resisted by a party of coal-heavers belonging to a wharf adjoining, who assailed them with coals and glass-bottles; several of the gang were cut in a most shocking manner, on their heads and legs, and a woman who happened to be in a wherry, was wounded in so dreadful a manner, that it is feared she will not survive… The impress on Saturday, both above and below Bridge, was the hottest that has been for some time; the boats belonging to the ships at Deptford were particularly active, and it is supposed they obtained upwards of two hundred men, who were regulated (sic) on board the Enterprize till late at night, and sent in the different tenders to the Nore, to be put on board such ships whose crews are not completed… The impressed men, for whom there was not room on board the Enterprize, on Saturday were put into the Tower, and the gates shut, to prevent any of them effecting their escape.”

Morning Herald, December 11, 1804: “A very smart press took place yesterday morning upon the river, and the west part of the town. A great many useful hands were picked up.”

Morning Post, May 8, 1805: “The embargo to which we alluded in our Paper of Monday has taken place. At two o’clock yesterday afternoon, orders for that purpose were issued at the Custom House, and upwards of a thousand able seamen are said to have been already procured for the Navy, from on board the ships in the river.”

Morning Post, April 11, 1808: “On Saturday the hottest press ever known took place on the Thames, when an unprecedented number of able seamen were procured for His Majesty’s service. A flotilla of small smacks was surrounded by one of the gangs, and the whole of the hands, amounting to upwards of a hundred, were carried off.”

These raids on seamen were not always conducted on “rose-water” principles, and the slightest resistance met with a cracked crown, or worse. Witness a case tried at the Kingston Assizes, March 22, 1800, where John Salmon, a midshipman in His Majesty’s navy, was indicted for the wilful murder of William Jones. The facts of the case were as follow. The prisoner was an officer on board His Majesty’s ship Dromedary, lying in the Thames off Deptford. He and his lieutenant, William Wright (who was charged with being present, and assisting), went on shore on the night of the 19th of February, with nine of the crew, on the impress service; Wright had a pistol, Salmon a dirk, one of the sailors a hanger, and the rest were unarmed. After waiting some time in search of prey, the deceased, and one Brown, accompanied by two women, passed by; they were instantly seized upon, and carried to a public-house, from whence they endeavoured to effect their escape; a scuffle ensued, in the course of which the deceased called out he had been pricked. At this time three men had hold of him – a sufficient proof that he was overpowered – and whoever wounded him, most probably did so with malice prepense. The poor fellow was taken, in this state, to a boat, and thence on board a ship, where, for a considerable time, he received no medical assistance. The women, who were with him, accompanied him to the boat, and he told them that the midshipman had wounded him, and that he was bleeding to death; that every time he fetched his breath, he felt the air rushing in at the wound. He was afterwards taken to the hospital, and there, in the face of death, declared he had been murdered by the midshipman. The case was thoroughly proved as to the facts, but the prisoner was acquitted of the capital charge of murder, and I do not know whether he was ever prosecuted for manslaughter.

Men thus obtained, could scarcely be expected to be contented with their lot, and, therefore, we are not surprised to hear of more than one mutiny – the marvel is there were so few. Of course, they are not pleasant episodes in history, but they have to be written about.

The first in this decade (for the famous mutiny at the Nore occurred in the previous century), was that on board the Danäe, 20 guns, Captain Lord Proby. It is difficult to accurately ascertain the date, for it is variously given in different accounts, as March 16th, 17th, and 27th, 1800; but, at all events, in that month the Danäe was cruising off the coast of France, with some thirty of her crew, and officers, absent in prizes, and having on board some Frenchmen who had been captured on board the privateer Bordelais, and had subsequently entered the English service. On board was one Jackson (who had been secretary to Parker, the ringleader of the Nore Mutiny in 1798), who had been tried for participation in that mutiny and acquitted, since when, he had borne a good character, refusing the rank of petty officer which had been offered to him, giving as a reason, that being an impressed man, he held himself at liberty to make his escape whenever he had a chance, whereas, if he took rank, he should consider himself a volunteer.

With him as a ringleader, and a crew probably containing some fellow sufferers, and the Frenchmen, who would certainly join, on board, things were ripe for what followed. The ship was suddenly seized, and the officers overpowered, Lord Proby and the master being seriously wounded. The mutineers then set all sail, and steered for Brest Harbour, and on reaching Camaret Bay, they were boarded by a lieutenant of La Colombe, who asked Lord Proby to whom he surrendered. He replied, to the French nation, but not to the mutineers. La Colombe and the Danäe then sailed for Brest, being chased by the Anson and Boadicæa, and would, in all probability, have been captured, had not false signals been made by the Danäe that she was in chase. Lord Proby had previously thrown the private code of signals out of his cabin window. They were all confined in Dinan prison.

The Hermione, also, was carried over to the enemy by a mutinous crew; but in October, 1800, was cut out of Porto Cavello, after a gallant resistance, by the boat’s crew of the Surprise, Captain Hamilton, and brought in triumph to Port Royal, Jamaica. On this occasion justice overtook two of the mutineers, who were hanged on the 14th of August – one in Portsmouth Harbour, the other at Spithead. Another of the mutineers, one David Forester, was afterwards caught and executed, and, before he died, he confessed (Annual Register, April 19, 1802), “That he went into the cabin, and forced Captain Pigot overboard, through the port, while he was alive. He then got on the quarter deck, and found the first lieutenant begging for his life, saying he had a wife and three children depending on him for support; he took hold of him, and assisted in heaving him overboard alive, and declared he did not think he would have taken his life had he not first took hold of him. A cry was then heard through the ship that Lieutenant Douglas could not be found: he took a lantern and candle, and went into the gun-room, and found the Lieutenant under the marine officer’s cabin. He called in the rest of the people, when they dragged him on deck, and threw him overboard. He next caught hold of Mr. Smith, a midshipman; a scuffle ensued, and, finding him likely to get away, he struck him with his tomahawk, and threw him overboard. The next cry was for putting all the officers to death, that they might not appear as evidence against them, and he seized on the Captain’s Clerk, who was immediately put to death.”

I have to chronicle yet one more mutiny, happily not so tragical as the last, but ending in fearful punishment to the mutineers. It occurred principally on board the Temeraire then in Bantry Bay, but pervaded the squadron; and the culprits were tried early in January, 1802, by a court martial at Portsmouth, for “using mutinous and seditious words, and taking an active part in mutinous and seditious assemblies.” Nineteen were found guilty, twelve sentenced to death, and ten, certainly, hanged.

There seems to have been no grumble about their pay, or food, or accommodation – a sea life was looked upon as a hard one, and accepted as such. The officers, at all events, did not get paid too well, for we read in the Morning Post, October 19, 1801: “We understand the Post Captains in the Navy are to have eight shillings a day instead of six. And it is supposed that Lieutenants will be advanced to four shillings instead of three.” They occasionally got a haul in prize money – like the Lively, which in August, 1805, was awarded the sum of £200,000 for the capture of some Spanish frigates.71

Spite of everything, the naval power of England reached the highest point it has ever attained, and no matter whatever grievances they may have been suffering from, the sailors, from the admiral to the powder monkey, behaved nobly in action, and, between the Navy and Army, we had rather more prisoners of war to take care of than was agreeable. Speaking of an exchange of prisoners, the Morning Post, October 15, 1810, says: “There are in France, of all kinds of prisoners and detained persons, about 12,000; in England there are about 50,000 prisoners,” and the disproportion was so great that terms could not be come to.

CHAPTER XLVIII

The Army – Number of men – Dress – Hair-powder – Militia – Commissions easily obtained – Price of substitutes – The Volunteers – Dress of the Honourable and Ancient Artillery Company – Bloomsbury Volunteers, and Rifle Volunteers – Review at Hatfield – Grand rising of Volunteers in 1803.

IN THE year 1800, our Army consisted of between 80,000 and 90,000 men, besides the foreign legions, such as the Bavarians, in our pay. In 1810, there were 105,000, foreigners not included.

The British soldier of that day was, outwardly, largely compounded of a tight coat and gaiters, many buttons and straps, finished off with hog’s lard and flour; and an excellent representation of him, in the midst of the decade, is taken from a memorial picture of the death of Nelson, and also from his funeral; but these latter may have been volunteers, as they were much utilized on that occasion. Be they what they may, both had one thing in common – the pig-tail – which was duly soaped, or larded and floured, until flour became so scarce that its use was first modified, and then discontinued, about 1808. Otherwise the variety of uniforms was infinite, as now.

Of the threatened Invasion I have already treated. Of the glorious campaigns abroad I have nothing to say, except that all did their duty, or more, with very few blunders, if we except the Expedition to the Scheldt. From the highest to the lowest, there was a wish to be with the colours. Fain would the Prince of Wales have joined any regiment of which he was colonel, on active service, and, in fact, he made application to be allowed to do so, but met with a refusal, at which he chafed greatly. Should any one be curious to read the “Correspondence between His Majesty, The Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, and Mr. Addington, respecting the Offer of Military Service made by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales,” it can be found in the appendix to the chronicle of the Annual Register for 1803, pp. 564, &c.

The Army was fighting our battles abroad, so that for the purposes of this book, we are left only to deal with the Militia and Volunteers. The Militia were in a state of almost permanent embodiment, except during the lull about 1802. March, 1803, saw them once more under arms; the Yeomanry had not been disembodied. Commissions in the Militia seem to have been easily procurable. Morning Post, December 3, 1800: “Militia Ensigncy. A young Gentleman of respectability can be introduced to an Ensigncy in the Militia, direct,” &c. Times, July 2, 1803: “An Adjutancy of English Militia to be sold,” &c. Substitutes could be bought, but at fluctuating prices, according to the chance of active service being required. When first called out in 1803, one could be got for £10; but the Times, September 15, 1803, in its Brighton news, says: “The price of substitutes now is as high as forty guineas, and this tempting boon, added to the stimulus of patriotism, has changed the occupation of many a Sussex swain.” The Annual Register, October 15, 1803, says: “Sixty pounds was last week paid at Plymouth for a substitute for the Militia. One man went, on condition of receiving 1s. per day during the war, and another sold himself for 7s. 3d. per lb.”

The Volunteer movement has been glanced at when treating of the threatened Invasion of 1803. There had, in the previous century, been a grand Volunteer force called into existence, but nothing like the magnificent general uprising that took place in 1803. Their uniforms, and accoutrements, nearly approached the regulars, as ours do now; but there was much more scope for individual fancy. The Honourable and Ancient Artillery Company wore a blue uniform, with scarlet and gold facings, pipe-clayed belts, and black gaiters. The Bloomsbury, and Inns of Court Volunteers dressed in scarlet, with yellow facings, white waistcoat and breeches, and black gaiters, whilst the Rifles were wholly clad in dark green.

The whole of the old Volunteers of 1798 did not disband; some old corps still kept on. On June 18, 1800, the King, accompanied by his family, the Ministers, &c., went to Hatfield, the seat of the Marquis of Salisbury, and there reviewed the Volunteers and Militia, to the number of 1,500, all of whom the Marquis most hospitably dined. Of this dinner I give a contemporary account, as it gives us a good insight into the fare of a public entertainment, especially one given by a nobleman, in honour of his sovereign and country: “80 hams, and as many rounds of beef; 100 joints of veal; 100 legs of lamb; 100 tongues; 100 meat pies; 25 rumps of beef roasted; 100 joints of mutton; 25 briskets; 25 edge bones of beef; 71 dishes of other roast beef; 100 gooseberry pies: besides very sumptuous covers at the tables of the King, the Cabinet Ministers, &c. For the country people, there were killed at the Salisbury Arms, 3 bullocks, 16 sheep, and 25 lambs. The expense is estimated at £3,000.”

There was a grand Volunteer Review on July 22, 1801, of nearly 5,000 men, by the Prince of Wales, supported by his two brothers, the Dukes of York and Kent, some 30,000 people being present.

But the moment invasion was threatened, there sprang, from the ground, armed men. A new levy of 50,000 regulars was raised, and the Volunteers responded to the call for men in larger numbers than they did in 1859-60. In 1804, the “List of such Yeomanry and Volunteer Corps as have been accepted and placed on the Establishment in Great Britain,” gives a total of 379,943 officers and men (effective rank and file 341,687), whilst Ireland furnished, besides 82,241 officers and men, a grand total of 462,184, against which we can but show some 214,000, less about 5,000 non-efficients, with a much larger population.

CHAPTER XLIX

Volunteer Regulations – The Brunswick Rifle – “Brown Bess” – Volunteer shooting – Amount subscribed to Patriotic Fund – Mr. Miller’s patriotic offer.

THE VOLUNTEERS were a useful body. They served as police, and were duly drummed to church on the National Fast and Thanksgiving days, to represent the national party; and, as I do not know whether the terms under which they were called into being, are generally known, I venture to transcribe them, even though they be at some length. Times, September 30, 1803:

“Regulationsfor theEstablishments, Allowances, &cofCorps and Companies of Volunteer Infantry,accepted subsequently to August 3, 1803 War Office, September 3, 1803.“A Regiment to consist of not more than 12 Companies, nor less than 8 Companies.

“A Battallion to consist of not more than 7 Companies, nor less than 4 Companies.

“A Corps to consist of not less than 3 Companies.

“Companies to consist of not less than 60, nor more than 120 Privates.

“To each Company 1 Captain, 1 Lieutenant, 1 Second Lieutenant or Ensign.

“It is, however, to be understood that where the establishment of any Companies has already been fixed at a lower number by Government, it is to remain unaltered by the Regulation.

“Companies of 90 Privates and upwards to have 2 Lieutenants and 1 Second Lieutenant or Ensign; or 3 Lieutenants, if a Grenadier or Light Infantry Company.

“Regiments consisting of 1,000 Privates to have 1 Lieut. – Col. Commandant, 2 Lieut. – Colonels, and 2 Majors.

“No higher rank than that of Lieut. – Col. Commandant to be given, unless where persons have, already, borne high rank in His Majesty’s forces.

“Regiments of not less than 800 Privates, to have 1 Lieut. – Col. Commandant, 1 Lieut. – Colonel, and 2 Majors.

“Regiments of not more than 480 Privates to have 1 Lieut. – Col. Commandant, 1 Lieut. – Colonel, and 1 Major.

“Battalions of less than 480 Privates to have 1 Lieut. – Colonel, and 1 Major.

“Corps consisting of 3 Companies, to have 1 Major Commandant, and no other Field Officer.

“Every Regiment of 8 Companies, or more, may have 1 Company of Grenadiers, and 1 Company of Light Infantry, each of which to have 2 Lieutenants instead of 1 Lieutenant, and 1 Second Lieutenant or Ensign.

“Every Battalion of 7 Companies, and not less than 4, may have 1 Company of Grenadiers, or 1 Company of Light Infantry, which Company may have 2 Lieutenants instead of 1, and 1 Second Lieutenant or Ensign.

“One Serjeant and 1 Corporal to every 20 Privates.

“One Drummer to every Company, when not called out into actual service.

“Two Drummers when called out.

“Staff.

“An Adjutant, Surgeon, Quarter-Master, and Serjeant-Major, may be allowed on the establishment of Corps of sufficient strength, as directed by the Militia Laws; but neither the said Staff Officers, nor any other Commissioned Officer, will have any pay or allowance whatever, except in the following cases, viz.:

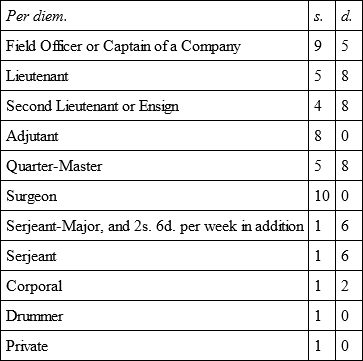

“If a Corps, or any part thereof, shall be called upon to act in cases of riot or disturbance, the charge of constant pay may be made for such services, for all the effective Officers and Men employed on such duty, at the following rates, the same being supported by a Certificate from His Majesty’s Lieutenant, or the Sheriff of the County; but, if called out in case of actual invasion, the corps is to be paid and disciplined in all respects, as the regular Infantry; the Artillery Companies excepted, which are then to be paid as the Royal Artillery.

“The only instances in which pay will be allowed, by Government, for any individual of the Corps when not so called out, are those of an Adjutant and Serjeant-Major, for whom pay will be granted at the rates following: Adjutant 6s. a day, Serjeant-Major 1s. 6d. per diem, and 2s. 6d. per week – in addition, if authorized by His Majesty’s Secretary of State, in consequence of a particular application from the Lord Lieutenant of the County, founded upon the necessity of the case; but this indulgence cannot be allowed under any circumstances unless the Corps to which the Adjutant may belong, shall consist of not less than 500 effective rank and file, and he shall have served at least five years as a Commissioned Officer in the Regulars, embodied Militia, Fencibles, or East India Company’s Service; and, unless the Corps to which the Serjeant-Major may belong, shall consist of not less than 200 effective rank and file, and he shall have served at least three years in some of His Majesty’s forces.

“Drill Serjeants of Companies are to be paid by the Parishes to which their respective Companies belong, as is provided in the 43rd Geo. III. cap. 120. sec. 11, and no charge to be made for them in the accounts to be transmitted to the War Office.

“Pay at the rate of one shilling per man per day for twenty days’ exercise within the year to the effective Non-commissioned Officers – (not being Drill Serjeants paid by the Parish) Drummers and Privates of the Corps, agreeably to their terms of service. No pay can be allowed for any man who shall not have attended for the complete period of twenty days.

“When a charge of constant pay is made for an Adjutant, or Serjeant-Major, his former services must be particularly stated in the pay list wherein the first charge is made.

“The allowance for clothing is twenty shillings per man, once in three years, to the effective non-commissioned officers, drummers, and privates of the Corps.

“The necessary pay lists will be sent from the War Office, addressed to the several Commandants, who will take care that the Certificates be regularly signed whenever the twenty days’ exercise shall have been completed, and the clothing actually furnished to the man. The allowance for the twenty days’ exercise may be drawn for immediately, and that for clothing, in one month from the receipt of such pay lists at the War Office, by bills, signed by the several Commandants, at thirty days’ sight, upon the general agent: unless any objection to the latter charges shall be signified officially to the said Commandant in the meantime.

“The whole to be clothed in red, with the exception of the Corps of Artillery, which may have blue clothing, and Rifle Corps, which may have green, with black belts.

“Serjeant-Major receiving constant pay and Drill Serjeants paid by the parish, to be attested, and to be subject to military law, as under 43 Geo. III. cap. 121.

“All applications for arms and accoutrements should be made through the Lord Lieutenant of the County, directly to the Board of Ordnance, and all applications for ammunition, for exercise, or practice, should be made through the inspecting Field Officers of Yeomanry and Volunteers to the Board of Ordnance annually. Ammunition for service should be drawn through the medium of the inspecting Field Officer, from the depôt under the orders of the General Officer of the District.

“The arms furnished by the Board of Ordnance to Corps of Volunteer Infantry are as follows: Musquets, complete with accoutrements; drummer’s swords; drums with sticks; spears for serjeants.

“The articles furnished to Volunteer Artillery by the Board of Ordnance, are pikes, drummer’s swords, and drums with sticks.

“Spears are allowed for Serjeants, and pikes to any extent for accepted men not otherwise armed.

“The following allowances, in lieu of accoutrements, &c., when required, may be obtained on application by the Commandant of the Corps to the Board of Ordnance: 10s. 6d. per set in lieu of accoutrements; 3s. each drummer’s sword belt; 2s. each drum carriage.

“Such Corps as have offered to serve free of expense, and have been accepted on those terms, can claim no allowance under these heads of service.

“Every Officer, Non-commissioned Officer, Corporal, Drummer, and Private Man, to take the oath of allegiance and fidelity to His Majesty, his heirs and successors.

“If the Commandant of a Corps should at any time desire an augmentation in the establishment thereof, or alteration in the title of the Corps, or the names, or dates of commissions of the officers, the same must be transmitted through the Lord Lieutenant of the County, in order to the amendment being submitted to His Majesty.

“All effective Members of Volunteer Corps and Companies accepted by His Majesty, are entitled to the exemptions from ballot allowed by 42 Geo. III. cap. 66, and Geo. III. cap. 121, provided that such persons are regularly returned in the muster rolls to be sent in to the Lord Lieutenant, or Clerk of the General Meetings of his County, at the times, in the manner, and certified upon honour by the Commandant, in the form prescribed by those Acts, and schedules thereto annexed.

“The Monthly Returns should be transmitted to the Inspecting Field Officer appointed to superintend the District in which the Corps is situated, and to the Secretary of State for the Home Department.”

Thus, we see that the regulations for the Volunteers were very similar to what they are now.

Of course the arms served out to them were, to our modern ideas, beneath contempt. There were a few Rifle Corps, who were armed with what was then called the Brunswick Rifle. It was short, because the barrel was very thick and heavy. The rifling was poly-grooved, the bullet spherical, and somewhat larger than the bore, so that when wrapped in a greased linen patch (carried in a box, or trap, in the butt of the gun) it required a mallet applied to the ramrod – to drive the bullet home – and fill up the grooves of the rifling. Of course it was a far superior weapon to the musket, or “Brown Bess”72– which was not calculated even to “hit a haystack” at thirty yards. The Morning Post, July 24, 1810, thus speaks of the shooting of a Corps: “The Hampstead Volunteers fired at a target yesterday on the Heath. Many excellent shots were fired, and some nearly entered ‘the Bull’s eye.’”