полная версия

полная версияThe Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Sir Francis replied that he should not have allowed him to have remained, and that he would not yield a voluntary assent to the warrant, but would only give in, in presence of an overwhelming force. The Serjeant-at-Arms then withdrew, having refused to be the bearer of a letter to the Speaker, which was afterwards conveyed to that dignitary by private hands. In this letter he asserted he would only submit to superior force, and insultingly said, “Your warrant, sir, I believe you know to be illegal. I know it to be so.”

On the morning of the 7th of April another attempt was made by a messenger of the House to serve him with the warrant and arrest him; but, although Sir Francis read it and put it in his pocket, he told the messenger that he might return and inform the Speaker that he would not obey it. The poor man said his orders were to remain there; but he was commanded to retire, and had to go.

Later in the day, between twelve and one, came a troop of Life Guards, who pranced up and down the road and pavement and dispersed the people, who heartily hissed them. A magistrate read the Riot Act; the troops cleared the road, and formed two lines across Piccadilly, where Sir Francis lived; and so strictly was this cordon kept, that they refused to allow his brother to pass to his dinner, until he was accompanied by a constable. Sir Francis wrote to the Sheriffs complaining of his house being beset by a military force.

No further attempt to execute the warrant was made that day, nor on the following day, which was Sunday.

But the majesty of Parliament would brook no further trifling, and on the Monday morning (April 9th), after breakfast, when “Sir Francis was employed in hearing his son (who had just come from Eton school) read and translate Magna Charta,” a man’s head was observed looking in at the window, the same man advertising his advent by smashing a pane or two of glass. Great credit was taken that no one threw this man off his ladder, but, probably, the sight of the troops in front of the house, acted as a deterrent. The civil authorities, however, had effected an entrance by the basement, and entered the drawing-room, where a pretty little farce was acted.

“The Serjeant-at-Arms said: ‘Sir Francis, you are my prisoner.’

“Sir Francis. By what authority do you act, Mr. Serjeant? By what power, sir, have you broken into my house, in violation of the laws of the land?

“Serjeant. Sir Francis, I am authorized by the warrant of the Speaker of the House of Commons.

“Sir Francis. I contest the authority of such a warrant. Exhibit to me the legal warrant by which you have dared to violate my house. Where is the Sheriff? Where is the Magistrate?

“At this time there was no magistrate, but he soon afterwards appeared.

“Serjeant. Sir Francis, my authority is in my hand: I will read it to you: it is the warrant of the Right Honourable the Speaker of the House of Commons.

“And here Mr. Colman attempted to read the warrant, but which he did with great trepidation.

“Sir Francis. I repeat to you, that it is no sufficient warrant. No – not to arrest my person in the open street, much less to break open my house in violation of all law. If you have a warrant from His Majesty, or from a proper officer of the King, I will pay instant obedience to it; but I will not yield to an illegal order.

“Serjeant. Sir Francis, I demand you to yield in the name of the Commons House of Parliament, and I trust you will not compel me to use force. I entreat you to believe that I wish to show you every respect.

“Sir Francis. I tell you distinctly that I will not voluntarily submit to an unlawful order; and I demand, in the King’s name, and in the name of the law, that you forthwith retire from my house.

“Serjeant. Then, sir, I must call in assistance, and force you to yield.

“Upon which the constables laid hold of Sir Francis. Mr. Jones Burdett and Mr. O’Connor immediately stepped up, and each took him under an arm. The constables closed in on all three, and drew them downstairs.

“Sir Francis then said: ‘I protest in the King’s name against this violation of my person and my house. It is superior force only that hurries me out of it, and you do it at your peril.’”

A coach was ready, surrounded by Cavalry, and Sir Francis and his friends entered it. The possibility of a popular demonstration, or attempt at rescue, was evidently feared, for the escort consisted of two squadrons of the 15th Light Dragoons, two troops of Life Guards, with a magistrate at their head; then came the coach, followed by two more troops of Life Guards, another troop of the 15th Light Dragoons, two battalions of Foot Guards, the rear being formed by another party of the 15th Light Dragoons. After escorting through Piccadilly, the Foot Guards left, and marched straight through the City, to await the prisoner at the Tower.

His escort went a very circuitous route, ending in Moorfields, the result of an arrangement between the authorities and the Lord Mayor, by which, if the one did not go through Temple Bar and the heart of the City, the Lord Mayor would exert all his authority within his bounds, as indeed he did, meeting, and heading, the cavalcade.

During his ride, Sir Francis, as might have been expected, posed, sitting well forward so that he might be well seen. It could hardly be from apathy, for the lower orders considered him as their champion; but, either from the body of accompanying troops, or the curious route taken, the journey to the Tower passed off almost without incident, except a little crying out, until the Minories was reached, when the East End – and it was a hundred times rougher than now – poured forth its lambs to welcome their shepherd. The over-awing force on Tower Hill prevented any absolute outbreak. There were shouts of “Burdett for ever!” and a few of the mob got tumbled into the shallow water of the Tower ditch, whence they emerged, probably all the better for the unwonted wash. No attempt at rescue seems to have been made, and the Tower gates were safely reached. The coach drew up; the Serjeant-at-Arms entered the little wicket to confer with the military authorities; the great gates swung open; the cannon boomed forth their welcome to the prisoner, and Sir Francis was safely caged.

Up to this time the roughs had had no fun; it had been tame work, and, if the military got away unharmed, it would have been a day lost; so brickbats, stones, and sticks were thrown at them without mercy. The soldiers’ tempers had been sorely tried; orders were given to fire, and some of the mob fell. The riot was kept up until the troops had left Fenchurch Street, and then the cost thereof was counted in the shape of one killed and eight wounded. A contemporary account says: “The confusion was dreadful, but the effect was the almost immediate dispersion of the mob in every direction. A great part of them seemed in a very advanced state of intoxication and otherwise infuriated to madness, for some time braving danger in every shape. In all the route of the military the streets were crowded beyond all possibility of description; all the shops were shut up, and the most dreadful alarm for some time prevailed.”

There were fears of another riot taking place when night fell, but preparations were made. The Coldstream Guards were under orders, and each man was furnished with thirty rounds of ball cartridge. Several military parties paraded the streets till a late hour, and the cannon in St. James’s Park were loaded with ball. Happily, however, all was quiet, and these precautions, although not unnecessary, were un-needed.

Next day the Metropolis was quiet, showing that the sympathy with the frothy hero of the hour, however loud it might be, was not deep. Even at the Tower, which contained all that there was of the origin of this mischief, the extra Guards were withdrawn, and ingress and egress to the fortress were as ordinarily – the prisoner’s friends being allowed to visit him freely. This episode may be closed with the consolatory feeling that the one man who was killed had been exceedingly active in attacking the military, and, at the moment when the shot was fired which deprived him of existence, he was in the act of throwing a brickbat at the soldiers. History does not record whether he was accompanied to his grave by weeping brother bricklayers.

We have seen that Sir Francis Burdett proffered a letter, addressed to the Speaker to the Serjeant-at-Arms, which the latter very properly refused to deliver, and, on the 9th of April, this letter formed the subject of a debate in the House of Commons. The Serjeant-at-Arms was examined by the House as to the particulars of the recalcitrant baronet’s arrest, and the Speaker added his testimony to the fact of his reproving the Serjeant for not obeying orders. The debate was adjourned until the next day, and it ended, according to Hansard, thus:

“It appearing to be the general sentiment that the Letter should not be inserted on the Journals, the Speaker said he would give directions accordingly. It being also understood that the Amendments moved should not appear on the Journals, the Speaker said he would give directions accordingly, and the question was put as an original motion, ‘That it is the opinion of this House, that the said Letter is a high and flagrant breach of the privileges of the House; but it appearing from the report of the Serjeant-at-Arms attending this House, that the warrant of the Speaker for the commitment of Sir Francis Burdett to the Tower has been executed, this House will not, at this time, proceed further on the said letter.’ Agreed nem con.”

Then followed a scene that has its parallel in our days, with another demagogue. Sir Francis Burdett commenced actions against the Speaker, the Serjeant-at-Arms, and the Earl of Moira, who was then Governor of the Tower. We know how easily petitions are got up, and this case was no exception; but Sir Francis was kept in well-merited incarceration, until the Prorogation of Parliament on the 21st of June, which set him free. The scene on his liberation is very graphically described by a contemporary:

“The crowd for some time continued but slowly to increase, but towards three o’clock, their numbers were rapidly augmented; and, shortly after three, as fitting a rabble as ever were ‘raked together’ appeared on Tower Hill. The bands in the neighbourhood frequently struck up a tune; and the assembled rabble as frequently huzzaed (they knew not why), and thus between them, for an hour or two, they kept up a scene of continual jollity and uproar.

“The Moorfields Cavalry35 had by this time arrived at the scene of action. Everything was prepared to carry Sir Francis (like the effigy of Guy Fawkes on the 5th of November) through the City. The air was rent by repeated shouts of ‘Burdett for ever!’ ‘Magna Charta!’ and ‘Trial by Jury!’ The blessings of the last, many of these patriots had doubtless experienced, and were, therefore, justified in expressing themselves with warmth. While these shouts burst spontaneously from the elated rabble, and every eye was turned towards the Tower, with the eagerness of hope, and the anxiety of expectation – on a sudden, intelligence was received that they had all been made fools of by Sir Francis, who, ashamed, probably, of being escorted through the City by such a band of ‘ragged rumped’ vagabonds, had left the Tower, crossed the water, and proceeded to Wimbledon.

“To describe the scene which followed – the vexation of the Westminster electors, the mortification of the Moorfields Cavalry, and the despair of ‘The Hope,’ in adequate colours, is impossible. Petrified by the news, for some time they remained on the spot undetermined how to act, and affecting to disbelieve the report. Unwilling, however, to be disappointed of their fondest hope – that of showing themselves– they determined on going through the streets in procession, though they could not accompany Sir Francis. The pageant accordingly commenced, the empty vehicle intended for Sir Francis took that part in the procession which he was to have taken, and the rational part of the mob consoled themselves by reflecting that, as they had originally set out to accompany emptiness they were not altogether disappointed.

“It was now proposed by some of the mob, that as they could not have the honour of escorting Sir Francis Burdett from the Tower, they should conclude the day by conducting Mr. Gale Jones from Newgate, and he, shortly after, fell into the procession in a hackney coach.

“On the arrival of the procession in Piccadilly, it went off to the northward, and the vehicles returned by a different route from that which they went. The whole of the streets and windows were crowded, from Tower Hill, to Piccadilly.

“About one o’clock a party of Burdettites from Soho, with blue cockades and colours flying, proceeded down Catherine Street, and the Strand, for the City. They marched two and two. At Catherine Street they were met by the 12th Light Dragoons on their way to Hyde Park Corner. The music of the former was playing St. Patrick’s Day. The Band of the Dragoons immediately struck up God save the King. The 14th Light Dragoons followed the 12th; both regiments mustering very strong. All the Volunteers were under orders; and the Firemen belonging to the several Insurance Offices paraded the streets, with music, acting as constables.”

CHAPTER XX

Good harvest – Thanksgiving for same – List of poor Livings – Another Jubilee – Illness and death of the Princess Amelia – Effect on the King – Prayers for his restoration to health – Funeral of the Princess – Curious position of the Houses of Parliament – Proposition for a Regency – Close of the first decade of the XIXth Century.

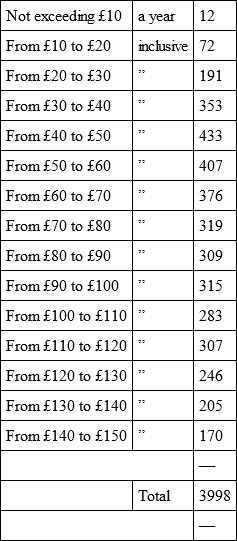

IT GIVES great pleasure to record that the Harvest this year was plentiful, so bountiful, indeed, as to stir up feelings of gratitude in the national breast, and induce the manufacture of a “Form of prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God, for His mercy in having vouchsafed to bestow on this Nation an abundant crop, and favourable harvest.” The farmers and laics benefited thereby, but the position of the Clergy at that time was far from being very high, at least with regard to worldly remuneration —vide the following:

Account of Livings in England and Wales under £150 a year

“Of these very small livings three are in the diocese of Lichfield and Coventry, three in that of Norwich, two in that of St. David’s, one in that of Llandaff, one in that of London, one in that of Peterborough, and one in that of Winchester.”

This does not show a very flourishing state of things, although money could be spent freely in support of foreign clergy as we see by the accounts for this year: “Emigrant clergy and laity of France, £161,542 2s.”

One would think that two Jubilees in one twelvemonth was almost too much of a good thing, but our great-grandfathers thought differently. There had already been one, to celebrate the fact of the King entering on the fiftieth year of his reign, they must now have one to chronicle its close. But, although there was somewhat of the “poor debtor” element introduced, it was by no means as enthusiastically received as it had been twelve months previously.

This time we hear more of festive meetings: a Jubilee Ball at the Argyle Rooms – then very decorous and proper – another at the New Rooms, Kennington, and a grand dinner at Montpelier House, whilst Camberwell, Vauxhall, Kennington, and Lambeth all furnished materials for festivity. Needless to say, there were new Jubilee medals.

But the poor old King was getting ill, and troubled about his daughter, the Princess Amelia, who lay a-dying. Poor girl! she knew she had not long to live, and she wished to give the King some personal souvenir. She had a very valuable and choice stone, which she wished to have made into a ring for him. As her great thought and most earnest wish was to give this to her father before her death, a jeweller was sent for express from London, and it was soon made, and she had her desire gratified. On His Majesty going to the bedside of the Princess, as was his daily wont, she put the ring upon his finger without saying a word. The ring told its own tale: it bore as an inscription her name, and “Remember me when I am gone.” A lock of her hair was also worked into the ring.

The mental anguish caused by this event, and by the knowledge that death was soon to claim the Princess, was too much for the King to bear. Almost blind, and with enfeebled intellect, he had not strength to bear up against the terrible blow.

At first the papers said he had a slight cold, but the next day it was found to be of no use concealing his illness. The Morning Post of the 31st of October says: “It is with hearfelt sorrow we announce that His Majesty’s indisposition still continues. It commenced with the effect produced upon his tender parental feelings on receiving the ring from the hand of his afflicted, beloved daughter, the affecting inscription upon which caused him, blessed and most amiable of men, to burst into tears, with the most heart-touching lamentations on the present state, and approaching dissolution, of the afflicted, and interesting Princess. His Majesty is attended by Drs. Halford, Heberden, and Baillie, who issue daily bulletins of the state of the virtuous and revered monarch, for whose speedy recovery the prayers of all good men will not fail to be offered up.” And there was public prayer made “for the restoration of His Majesty’s health.”

The Princess Amelia died on the 2nd of November, and was buried with due state. In her coffin were “8,000 nails – 6000 small and 2,000 large; eight large plates and handles resembling the Tuscan Order; a crown at the top, of the same description as issued from the Heralds’ Office; two palm branches in a cross saltier, under the crown, with P. A. (the initials of her Royal Highness). They are very massy, and have the grandest effect, being executed in the most highly-finished style, and neat manner possible. Forty-eight plates, with a crown, two palm branches in cross saltier, with the Princess Royal’s coronet at top; eight bevil double corner plates, with the same ornaments inscribed, and one at each corner of the cover.”

The King’s illness placed Parliament in a very awkward position. It stood prorogued till the 1st of November, on which day both Houses met, but sorely puzzled how to proceed, because there was no commission, nor was the King in a fit state to sign one. The Speaker took his seat, and said, “The House is now met, this being the last day to which Parliament was prorogued; but I am informed, that notwithstanding His Majesty’s proclamation upon the subject of a farther prorogation, no message is to be expected from His Majesty’s commissioners upon that subject, no commission for prorogation being made out. Under such circumstances I feel it my duty to take the chair, in order that the House may be able to adjourn itself.” And both Houses were left to their own devices. The head was there, but utterly incompetent to direct.

So they kept on, doing no public work, but examining the King’s physicians as to his state. They held out hopes of his recovery – perhaps in five or six months, perhaps in twelve or eighteen; but, in the meantime, really energetic steps must be taken to meet the emergency. On the 20th of November the Chancellor of the Exchequer moved three resolutions embodying the facts that His Majesty was incapacitated by illness from attending to business, and that the personal exercise of the royal authority is thereby suspended, therefore Parliament must supply the defect. It was then that the Regency of the Prince of Wales was proposed, and in January, 1811, an Act was passed, entitled, “An Act to provide for the Administration of the Royal Authority, and for the Care of the Royal Person during the Continuance of His Majesty’s illness, and for the Resumption of the Exercise of the Royal Authority.” The Prince of Wales was to exercise kingly powers, which, however, were much shorn in the matters of granting peerages, and granting offices and pensions; whilst the Queen, assisted by a Council, was to have the care of His Majesty’s person, and the direction of his household.

As a proof of the sympathy evinced by the people with the King in his illness, all pageantry was omitted on the 9th of November, when the Lord Mayor went to Westminster to be sworn in.

At the close of 1810 the National Debt amounted to the grand total of £811,898,083 12s. 3¾d. Three per Cent. Consols began at 70¾, touched in July 71½, and left off in December 66¼. Wheat averaged 95s. per quarter, and the quartern loaf was, in January, 1s. 4¼d.; June, 1s. 5d.; December, 1s. 3d.

Here ends the chronicle of the First Decade of the Nineteenth Century.

CHAPTER XXI

The roads – Modern traffic compared with old – The stage coach – Stage waggons – Their speed – Price of posting – The hackney coach – Sedan chairs – Horse riding – Improvement in carriages.

PERHAPS as good a test as any, of the civilization of a nation, is its roads. From the mere foot-tracks of the savage, to the broader paths necessarily used when he had brought the horse into subjugation, mark a distinct advance. When the wheeled carriage was invented, a causeway, artificially strengthened, must be made, or the wheels would sink into the soft earth, and make ruts, which would need extra power in order to extricate the vehicle; besides the great chance there was of that vehicle coming to utter grief. Settlers in Africa and Australia can yet tell tales of the inconveniences of a land without roads.

To the Romans, as for much else of our civilization, we are indebted for our knowledge of road making – nay, even for some of our roads still existing – but these latter were the main arteries of the kingdom, the veins had yet to be developed. That roads mean civilization is apparent, because without them there could be little or no intercommunication between communities, and no opportunity for traffic and barter with each other. We, in our day, have been spoilt, by, almost suddenly, having had a road traffic thrown open to us, which renders every village in our Isles, of comparatively easy access, so that we are apt to look with disfavour on the old times. Seated, or lying, in the luxurious ease of a Pullman car – going at sixty miles an hour – it is hard to realize a tedious journey by waggon, or even an outside journey by the swifter, yet slow, mail or stage coach, with its many stoppages, and its not altogether pleasant adventures. For, considering the relative numbers of persons travelling, there were far more accidents, and of a serious kind, than in these days of railways. It was all very well, on the introduction of steam to say, “If you are upset off a coach, why there you are! but if you are in a railway accident, where are you?” The coach might break down, as it often did, a wheel come off, or an axle, or a pole break – or the coach might be, as it ofttimes was, overloaded, and then in a rut – why, over all went. The horses, too, were apt to cast shoes, slip down, get their legs over the traces, or take to kicking, besides which the harness would snap, either the traces, or the breeching, or the reins, and these terrors were amplified by the probability of encountering highwaymen, who were naturally attracted to attack the stage coaches, not only on account of the money and valuables which the passengers carried with them, but because parcels of great price were entrusted to the coachman, such as gold, or notes and securities, for country banks, remittances between commercial firms, &c.

In the illustration showing a stage coach, it will be seen that there is a supplementary portion attached, made of wicker-work, and called “the basket.” This was for the reception of parcels. The mail coaches, which took long, direct routes, will be spoken of under the heading of Post Office.

Inconvenient to a degree, as were these stage coaches, with exposure to all changes of weather, if outside – or else cooped up in a very stuffy inside, with possibly disagreeable, or invalid, companions – they were the only means of communication between those places unvisited by the mail coach, and also for those which required a more frequent service. They were very numerous, so much so that, although I began to count them, I gave up the task, as not being “worth the candle.”