полная версия

полная версияHistorical Record of the Fourth, or Royal Irish Regiment of Dragoon Guards

Richard Cannon

Historical Record of the Fourth, or Royal Irish Regiment of Dragoon Guards

PREFACE

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour, by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object, than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honourable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the 'London Gazette,' from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery, and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign's Approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command, that every Regiment shall in future keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service, and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor, – on their sufferings, – and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services, and of acts of individual bravery, can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty's special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant-General's Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps– an attachment to every thing belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, – the valiant, – the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilised people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood, "firm as the rocks of their native shore;" and when half the World has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war, – victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, – our brothers – our fellow-citizens in arms, – a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us, will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers, will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed, the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

INTRODUCTION

The ancient Armies of England were composed of Horse and Foot; but the feudal troops established by William the Conqueror in 1086, consisted almost entirely of Horse. Under the feudal system, every holder of land amounting to what was termed a "knight's fee," was required to provide a charger, a coat of mail, a helmet, a shield, and a lance, and to serve the Crown a period of forty days in each year at his own expense; and the great landholders had to provide armed men in proportion to the extent of their estates; consequently the ranks of the feudal Cavalry were completed with men of property, and the vassals and tenants of the great barons, who led their dependents to the field in person.

In the succeeding reigns the Cavalry of the Army was composed of Knights (or men at arms) and Hobiliers (or horsemen of inferior degree); and the Infantry of spear and battle-axe men, cross-bowmen, and archers. The Knights wore armour on every part of the body, and their weapons were a lance, a sword, and a small dagger. The Hobiliers were accoutred and armed for the light and less important services of war, and were not considered qualified for a charge in line. Mounted Archers1 were also introduced, and the English nation eventually became pre-eminent in the use of the bow.

About the time of Queen Mary the appellation of "Men at Arms" was changed to that of "Spears and Launces." The introduction of fire-arms ultimately occasioned the lance to fall into disuse, and the title of the Horsemen of the first degree was changed to "Cuirassiers." The Cuirassiers were armed cap-à-pié, and their weapons were a sword with a straight narrow blade and sharp point, and a pair of large pistols, called petrenels; and the Hobiliers carried carbines. The Infantry carried pikes, matchlocks, and swords. The introduction of fire-arms occasioned the formation of regiments armed and equipped as infantry, but mounted on small horses for the sake of expedition of movement, and these were styled "Dragoons;" a small portion of the military force of the kingdom, however, consisted of this description of troops.

The formation of the present Army commenced after the Restoration in 1660, with the establishment of regular corps of Horse and Foot; the Horsemen were cuirassiers, but only wore armour on the head and body; and the Foot were pikemen and musketeers. The arms which each description of force carried, are described in the following extract from the "Regulations of King Charles II.," dated 5th May, 1663: —

"Each Horseman to have for his defensive armes, back, breast, and pot; and for his offensive armes, a sword, and a case of pistolls, the barrels whereof are not to be undr. foorteen inches in length; and each Trooper of Our Guards to have a carbine, besides the aforesaid armes. And the Foote to have each souldier a sword, and each pikeman a pike of 16 foote long and not undr.; and each musqueteer a musquet, with a collar of bandaliers, the barrels of which musquet to be about foor foote long, and to conteine a bullet, foorteen of which shall weigh a pound weight2."

The ranks of the Troops of Horse were at this period composed of men of some property – generally the sons of substantial yeomen: the young men received as recruits provided their own horses, and they were placed on a rate of pay sufficient to give them a respectable station in society.

On the breaking out of the war with Holland, in the spring of 1672, a Regiment of Dragoons was raised3; the Dragoons were placed on a lower rate of pay than the Horse; and the Regiment was armed similar to the Infantry, excepting that a limited number of the men carried halberds instead of pikes, and the others muskets and bayonets; and a few men in each Troop had pistols; as appears by a warrant dated the 2nd of April, 1672, of which the following is an extract: —

"Charles R."Our will and pleasure is, that a Regiment of Dragoones which we have established and ordered to be raised, in twelve Troopes of fourscore in each beside officers, who are to be under the command of Our most deare and most intirely beloved Cousin Prince Rupert, shall be armed out of Our stoares remaining within Our office of the Ordinance, as followeth; that is to say, three corporalls, two serjeants, the gentlemen at armes, and twelve souldiers of each of the said twelve Troopes, are to have and carry each of them one halbard, and one case of pistolls with holsters; and the rest of the souldiers of the several Troopes aforesaid, are to have and to carry each of them one matchlocke musquet, with a collar of bandaliers, and also to have and to carry one bayonet4, or great knife. That each lieutenant have and carry one partizan; and that two drums be delivered out for each Troope of the said Regiment5."

Several regiments of Horse and Dragoons were raised in the first year of the reign of King James II.; and the horsemen carried a short carbine6 in addition to the sword and pair of pistols: and in a Regulation dated the 21st of February, 1687, the arms of the Dragoons at that period are commanded to be as follow: —

"The Dragoons to have snaphanse musquets, strapt, with bright barrels of three foote eight inches long, cartouch-boxes, bayonetts, granado pouches, bucketts, and hammer-hatchetts."

After several years' experience, little advantage was found to accrue from having Cavalry Regiments formed almost exclusively for engaging the enemy on foot; and, the Horse having laid aside their armour, the arms and equipment of Horse and Dragoons were so nearly assimilated, that there remained little distinction besides the name and rate of pay. The introduction of improvements into the mounting, arming, and equipment of Dragoons rendered them competent to the performance of every description of service required of Cavalry; and, while the long musket and bayonet were retained, to enable them to act as Infantry, if necessary, they were found to be equally efficient, and of equal value to the nation, as Cavalry, with the Regiments of Horse.

In the several augmentations made to the regular Army after the early part of the reign of Queen Anne, no new Regiments of Horse were raised for permanent service; and in 1746 King George II. reduced three of the old Regiments of Horse to the quality and pay of Dragoons; at the same time, His Majesty gave them the title of First, Second, and Third Regiments of Dragoon Guards: and in 1788 the same alteration was made in the remaining four Regiments of Horse, which then became the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Regiments of Dragoon Guards.

At present there are only three Regiments which are styled Horse in the British Army, namely, the two Regiments of Life Guards, and the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards, to whom cuirasses have recently been restored. The other Cavalry Regiments consist of Dragoon Guards, Heavy and Light Dragoons, Hussars, and Lancers; and although the long musket and bayonet have been laid aside by the whole of the Cavalry, and the Regiments are armed and equipped on the principle of the old Horse (excepting the cuirass), they continue to be styled Dragoons.

The old Regiments of Horse formed a highly respectable and efficient portion of the Army, and it is found, on perusing the histories of the various campaigns in which they have been engaged, that they have, on all occasions, maintained a high character for steadiness and discipline, as well as for bravery in action. They were formerly mounted on horses of superior weight and physical power, and few troops could withstand a well-directed charge of the celebrated British Horse. The records of these corps embrace a period of 150 years – a period eventful in history, and abounding in instances of heroism displayed by the British troops when danger has threatened the nation, – a period in which these Regiments have numbered in their ranks men of loyalty, valour, and good conduct, worthy of imitation.

Since the Regiments of Horse were formed into Dragoon Guards, additional improvements have been introduced into the constitution of the several corps; and the superior description of horses now bred in the United Kingdom enables the commanding officers to remount their regiments with such excellent horses, that, whilst sufficient weight has been retained for a powerful charge in line, a lightness has been acquired which renders them available for every description of service incident to modern warfare.

The orderly conduct of these Regiments in quarters has gained the confidence and esteem of the respectable inhabitants of the various parts of the United Kingdom in which they have been stationed; their promptitude and alacrity in attending to the requisitions of the magistrates in periods of excitement, and the temper, patience, and forbearance which they have evinced when subjected to great provocation, insult, and violence from the misguided populace, prove the value of these troops to the Crown, and to the Government of the country, and justify the reliance which is reposed on them.

HISTORICAL RECORD OF THE FOURTH, OR ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT OF DRAGOON GUARDS

1685The Regiment, which forms the subject of the following memoir, is one of the seventeen corps, now in the British army, which derive their origin from the commotions in England during the first year of the reign of King James II.

The origin of these commotions may be traced to the pernicious councils adopted by King Charles I., which were followed by a flame of puritanical zeal and of democratical fury and outrage in the country, which deprived the monarch of life, and forced the royal family to reside for several years in exile on the continent, where King Charles II. and his brother, James Duke of York, imbibed the doctrines of the Church of Rome. After the Restoration, in 1660, the King concealed his religion from his Protestant subjects; but the Duke of York openly avowed the tenets of the Roman Catholic Church, which rendered him exceedingly unpopular. King Charles II. having no legitimate issue, his eldest illegitimate son, James Duke of Monmouth, an officer of some merit, who had espoused the Protestant cause with great warmth, and had become very popular, aspired to the throne. In a few months after the accession of James II., this nobleman arrived from Holland (11th June, 1685) with a band of armed followers, and erecting his standard in the west of England, called upon the people to aid him in gaining the sovereign power.

Although a deep feeling of anxiety was general in the kingdom at this period, yet the King had declared his determination to support the Protestant religion, as by law established, and his designs against the constitution had not been manifested; hence loyalty to the sovereign, a principle so genial to the innate feelings of the British people, prevailed over every other consideration. A number of Mendip miners and other disaffected persons joined the Duke of Monmouth; but men of all ranks arrayed themselves under the banners of royalty.

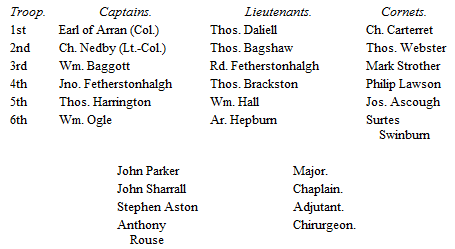

To officers and soldiers imbued with a laudable esprit de corps, the particulars relating to the origin and services of their regiment are of intense interest, and the circumstances which gave rise to the formation of their corps are of themselves an era. To encourage such feelings is one of the objects of the present undertaking, and, although the general reader may think the narrative tedious, the officers and men of the Royal Irish Dragoon Guards will feel gratified at learning by whom, and where, each troop, of which their regiment was originally composed, was raised. This information has been procured from public documents, in which it is recorded that, in the midst of the hostile preparations which the Duke of Monmouth's rebellion occasioned in every part of the kingdom, a troop of horse was raised by James Earl of Arran, eldest son of William Duke of Hamilton, a nobleman distinguished alike for loyalty and attachment to the Protestant religion; a second troop was raised, in the vicinity of London, by Captain John Parker, Lieutenant of the Horse Grenadier Guards attached to the King's Own troop of Life Guards (now First Regiment of Life Guards); a third at Lichfield, by William Baggott, Esq.; a fourth at Grantham, by Thomas Harrington, Esq.; a fifth at Durham, by John Fetherstonhalgh, Esq.; and the sixth at Morpeth, by William Ogle, Esq.; and that, after the decisive battle of Sedgemoor had destroyed the hopes of the invader, these six troops were ordered to march to the south of England, and were incorporated into a regiment of Cuirassiers, which is now the Fourth or Royal Irish Regiment of Dragoon Guards. The Colonelcy was conferred on the Earl of Arran, by commission, dated the 28th of July, 1685; the Lieutenant-Colonelcy on Captain Charles Nedby,7 from the Queen's regiment of horse; and the commission of Major on Captain John Parker.

At the formation of this regiment it ranked as Sixth Horse, but was distinguished by the name of its Colonel, the practice of using numerical titles not having been introduced into the British army until the reign of King George II. This corps being composed of the sons of substantial yeomen and tradesmen, who provided their own horses, it was held in high estimation in the country, and the men were placed on a rate of pay (2s. 6d. per day) which gave them a respectable station in society. Few nations in Europe possessed a body of troops which could vie with the English horse in all the qualities of good soldiers, and, in the reigns of King William III. and Queen Anne, this arme acquired a celebrity for gallantry and good conduct; and these qualities, whether evinced by bravery in the field, or by steadiness and temperate behaviour when their services have been required on home duties, have proved their usefulness, and have rendered them valuable corps during succeeding reigns.

The Earl of Arran's Regiment was armed and equipped, in common with the other regiments of Cuirassiers, with long swords, a pair of long pistols, and short carbines; the men wore hats, with broad brims bound with narrow lace, turned up on one side, and ornamented with ribands; large boots; and gauntlet gloves; their defensive armour was steel cuirasses, and head-pieces. This regiment was distinguished by white ribands, white linings to the coat, white waistcoats and breeches, white horse-furniture, the carbine belts covered with white cloth, and ornamented with lace, and the officers wore white silk sashes; – each regiment had a distinguishing colour, which was then called its livery, and which is now called facing, and the distinguishing colour of the Earl of Arran's Regiment was WHITE.8

On their arrival in the south of England, Arran's Cuirassiers proceeded to the vicinity of Hounslow, and on the 20th of August passed in review before King James II. and his court on the heath. In order to make a display of his power and to overawe the disaffected in the kingdom, His Majesty ordered an army of eight thousand men to encamp on Hounslow Heath, of which this regiment formed a part; and on the 22nd of August the King reviewed twenty squadrons of horse, one of horse-grenadier guards, one of dragoons, and ten battalions of foot on the heath. After the review Arran's Cuirassiers marched into quarters at Winchester and Andover, where they arrived on the 5th of September.

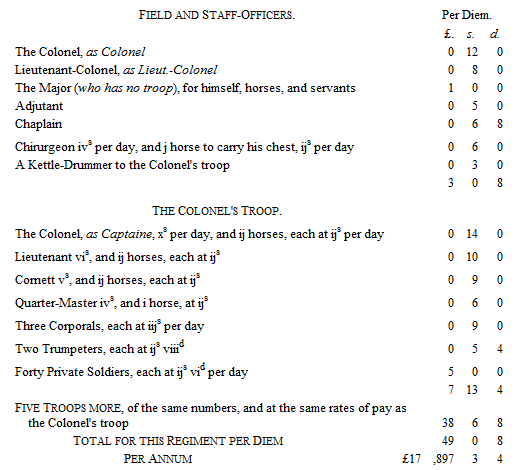

1686In these quarters the regiment passed the succeeding winter; and on the 1st of January, 1686, its establishment was fixed by a warrant under the sign manual, from which the following is an extract: —

THE EARL OF ARRAN'S REGIMENT OF HORSE

At this period the following officers were holding commissions in the regiment: —

Arran's Cuirassiers were called from their cantonments in Hampshire in June, and again pitched their tents on Hounslow Heath, where they were reviewed several times by the King; and afterwards marched into quarters at Leicester, Ashby de la Zouch, Loughborough, and Melton Mowbray; and while in these quarters their Lieutenant-Colonel retired, and was succeeded by Major John Parker.

1687In the following summer they were withdrawn from Leicestershire, and proceeding to the metropolis, occupied quarters for a short time at Chelsea and Knightsbridge, from whence they proceeded to Hounslow, and again pitched their tents on the heath. After having been reviewed by the King, they marched (9th August) to Windsor and adjacent villages, and furnished a guard for the royal family at Windsor Castle; also a guard for the Princess Anne (afterwards Queen Anne) at Hampton Court Palace, and one troop was stationed at London to assist the Life Guards in their attendance on the Court.

On the 31st of August the regiment marched to London, and was quartered in Holborn, Gray's Inn Lane, and the vicinity of Smithfield, in order to take part in the duties of the court and metropolis; and in September it furnished a detachment to protect a large sum of money from London to Portsmouth.

1688Having been relieved from the King's duty, Arran's Cuirassiers marched to Richmond and adjacent villages in May, 1688; and in July they once more encamped on Hounslow Heath. After taking part in several reviews, mock-battles, and splendid military spectacles, which were exhibited on the Heath by a numerous army, they proceeded to Cambridge, Peterborough, and St. Ives, and afterwards to Ipswich, where they were stationed a short time under Major-General Sir John Lanier, but were suddenly ordered to march to London in the beginning of November.

The circumstances in which the loyal officers and soldiers of the King's army were placed were of a most painful character. The King had been making rapid advances towards the subversion of the established religion and laws of the kingdom; and loyalty to the sovereign, – a distinguished feature in the character of the British soldier, and the love of the best interests of their native country, – which is inherent in men, were become so opposed to each other, that it appeared necessary for one to be sacrificed. Arran's Cuirassiers were, however, spared this painful ordeal by the circumstances which occurred. The King had resolved to remodel his army in England by the dismissal of Protestants and the introduction of Papists, as he had already done in Ireland; but the arrival of the Prince of Orange, with a Dutch army to aid the English nobility in opposing the proceedings of the Court, overturned the King's measures. The loyalty and attachment to the King evinced by the Earl of Arran occasioned him to be promoted to the rank of Brigadier-General, and his regiment was considered one of the corps on which dependence could be placed. It had completed an augmentation of ten men per troop ordered in September, and was selected to remain as a guard near the Queen and the infant Prince of Wales, who was afterwards known as the Pretender: but a defection appearing in the army, the infant Prince was sent to Portsmouth; and the regiment, having been released from its duty of attendance on the Queen, was ordered to march to Salisbury.