полная версия

полная версияNotes of a naturalist in South America

In the Pacific region we have direct evidence to this effect, in the fact that in Hawaii, and elsewhere, the side of the islands exposed to the trade-winds is that of heavy rainfall, and is generally covered with forest. No sufficient data exist for estimating the amount of vapour thus carried back to the tropics from high latitudes on both sides of the equator, nor the amount of heat set free by its condensation; but we may form some conception of its probable amount by considering that at the moderate estimate of a mean annual rainfall of seventy-two inches for the portion of the globe between the tropics, this amounts to a yearly fall of 88,737 cubic miles, and that we can scarcely reckon the share of this great volume of water supplied by evaporation from the same part of the globe at more than one-half. Still less is it possible to calculate the amount of vapour annually transferred from the northern to the southern hemisphere, which goes to neutralize the apparent effect of the diversion of portions of the equatorial waters to the north side of the line. In the Atlantic basin it is probable that the larger part of the rainfall in the region including and surrounding the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea is supplied by vapour carried from the temperate zone by the north-east trade-winds. There is some reason to believe that a portion of the rainfall of the great basin of the Amazons, south of the line, is also supplied from the same source. Several travellers report that during the rainy season the prevailing winds are from the west and north-west, the latter being especially predominant at Iquitos, about 4° S. latitude, and 1600 miles from the mouth of the river.

In tropical Australia the rainy season falls during the prevalence of the north-west monsoon, and we cannot doubt that this is mainly supplied by vapour carried from the northern hemisphere. Another region wherein the same phenomenon is exhibited on a large scale is the central portion of Polynesia, extending from the Feejee to the Society Islands over a space of at least twenty degrees of longitude. Over that wide area, as far as about twenty degrees south of the line, the regular south-east trade-wind prevails only in the winter of the southern hemisphere, while during the rest of the year, especially in summer, north and north-east winds have the predominance. Taking the mean of three stations in the Feejee Islands, of which the returns are given by Dr. Hann, I find in round numbers the very large amount of 150 inches for the mean annual rainfall, of which 105 fall during the seven months from October to April, while the five colder months from May to September supply only forty-five inches of rain. There can be little doubt that the larger part of the 105 inches falling during the warm season is derived from the northern hemisphere.

I by no means seek to account fully for the apparent contradiction between the results of theory, as developed by Dr. Croll, and the actual distribution of heat over the earth as proved by observation; but I venture to think that I have shown reason to doubt the possibility of drawing absolute conclusions as to the results of astronomical changes until we shall have fuller knowledge than we now possess of all the agencies that regulate climates.

Before concluding these remarks, I will notice one other branch of the argument in regard to which I am unable to concur with Mr. Croll. As we have seen, the essential point in his theory as to the modus operandi of changes of eccentricity, and the relative position of the poles, on the distribution of temperature, is that the currents of the equatorial zone are driven towards the pole which has the summer in aphelion, and that the cause of this shifting of the currents depends on the greater strength of the trade-winds in the hemisphere which has the winter in aphelion; the strength of the trade-winds in turn depending on the amount of difference of temperature between the equatorial and the colder zones. Taking the surface of the earth generally, the trade-winds of the southern are probably stronger than those of the northern hemisphere, and, if it were true that the south temperate and frigid zones were colder than those of the other hemisphere, it would be allowable to argue that the greater difference of temperature as compared with the equatorial zone was the cause of the greater strength of the trade-winds. But we now certainly know that the southern hemisphere between latitudes 45° and 55° is considerably warmer than the corresponding zone of the northern hemisphere, and we have good grounds for believing that the mean temperature of the whole hemisphere south of latitude 45° is higher, and certainly not lower, than that of the same portion of the northern hemisphere. We are therefore not justified in explaining the greater strength of the southern trade-winds by a greater inequality of temperature between the equator and the pole.

In my opinion the cause of this predominance of the southern trade-winds is to be sought in the fact that the southern is mainly a water hemisphere, while the northern is in great part a land hemisphere. In the south, the great currents of the atmosphere flow with scarcely any interruption, except that caused by Australia, where, in fact, the trade-winds are irregular, and lose their force. In the northern hemisphere the various winds originating in the unequal heating of the land surface interfere with the normal force of the trade-winds, and weaken their effect.

In connection with this branch of the subject, I may remark that the belief in the greater cold of the southern hemisphere mainly rests on the fact that all the land hitherto seen in high latitudes has been mountainous, and is covered by great accumulations of snow and ice. But this does not in itself justify the conclusion that the mean temperature is extremely low. It is true that the fogs which ordinarily rest on a snow-covered surface much diminish the effect of solar radiation during the summer in high latitudes, but this is compensated by the great amount of heat liberated in the condensation of vapour. The only part of the earth which is now believed to be covered with an ice-sheet is Greenland, but the mean of the observations in that country shows a temperature higher by at least 10° Fahr. than that of Northern Asia, where the amount of snowfall is very slight, and rapidly disappears during the short arctic summer. If there be, as some persons believe, a large tract of continental land surrounding the south pole, I should expect to find that the great accumulations of snow and ice are confined to the coast regions. In that case the mean temperature of the region within the antarctic circle would probably be lower than it would be in the supposition, which appears to me more probable, that the lands hitherto seen belong to scattered mountainous islands. If, from any combination of causes, one pole of the earth has ever been brought to a mean temperature much lower than that now experienced, I should expect to find that the phenomena of glaciation would be exhibited towards the equatorial limit of the cold zone, rather than in the portions near the pole. The formation of land-ice depends on the condensation of vapour, and before air-currents could reach the centre of an area of extreme cold the contained vapour would have been condensed. This consideration alone suffices, to my mind, to make the supposition of a polar ice-cap in the highest degree improbable.

Mr. Wallace (“Island Life,” p. 142) cites, as conclusive evidence of the effect of winter in aphelion in producing glaciation, the facts, to which attention was first directed by Darwin, as to the depression of the line of perpetual snow, and the consequent extension of great glaciers, on the west coast of Southern Chili. I have adverted to this subject in the text (p. 229), and I may further remark that if winter in aphelion be the cause of the depression of the snow-line in latitude 41° S., it can scarcely fail to produce some similar effect in latitude 34° S. Yet we find on the southern limit the snow-line much lower, and at the northern much higher, than it has ever been observed in corresponding latitudes in the northern hemisphere, the line being depressed by more than 8000 feet within a distance of only seven degrees of latitude. The explanation, as I have ventured to maintain, is altogether to be found in the extraordinary rainfall of Southern Chili; and to the same cause we must attribute the fact that, in spite of the greater distance of the sun, the winter temperature is higher than in most places in corresponding latitudes in the northern hemisphere. At Ancud in Chiloe, in latitude 41° 46′, the temperature of the coldest month is lower by less than three and a half degrees of Fahrenheit than it is at Coimbra in Portugal, one and a half degree nearer the equator, in the region which receives the full warming effect of the Gulf-stream.

I should have expressed myself ill in the preceding pages if I should be supposed to deny that, in his writings on this subject, Mr. Croll has made an important contribution to the physics of geology. He has, in my humble opinion, been the first to recognize the full importance of one of the agencies which, under possible conditions, may have profoundly affected the climate of the globe during past epochs, although I do not believe that, in the present state of our knowledge, we can safely draw those positive inferences at which he has arrived. Even those who are unable to accept any portion of his theory as to the causes of past changes of climate must feel indebted to his writings for numerous valuable suggestions, and for the removal of many popular opinions which his acute criticism has shown to be untenable.

FOOTNOTES

There is reason to think that the temperature for July, 1869, given above was exceptionally low, and although the months during which fogs prevail are abnormally cool for a place within 13° of the equator, I believe that the thermometer rarely falls below 60° Fahr.

1

For a list of the plants collected here, see a paper in the Journal of the Linnæan Society, vol. xxii.

2

Much cinchona bark, coming from the interior, was formerly shipped at Tumaco; but between horrible roads and the reckless waste of the forests through mismanagement, but little is now conveyed by this way.

3

For a list of the species collected, see the Journal of Linnæan Society, vol. xxii.

4

The abrupt change in the vegetation on this part of the American coast has been noticed by Humboldt, Weddell, and other scientific travellers. In a note to the French edition of Grisebach (“Vegetation du Globe,” traduit par P. de Tchihatcheff, ii. p. 615), M. André expresses the opinion that this, as well as some other cases of abrupt change in the vegetation observed by him in Colombia, are to be explained by the nature of the soil, which in the arid tracts is sandy or stony, and fails to retain moisture. Admitting that in certain cases this may afford a partial explanation of the facts, it is scarcely conceivable that the limit of the zone wherein little or no rain falls should exactly coincide with a change in the constitution of the soil, and I should be more disposed to admit a reversed order of causation, the porous and mobile superficial crust remaining in those tracts where, owing to deficient rainfall, there is no formation of vegetable mould, and no accumulation of the finer sediment forming a retentive clay.

5

The only detailed account of the operations that I have seen is in a work entitled, “Histoire de la Guerre du Pacifique,” by Don Diego Barros Arana. Paris: 1881. It appears to be fairly accurate as to facts, but coloured by very decided Chilian sympathies.

6

The heights given in the text are those of the railway stations.

7

Of 138 genera of Helianthoïdeæ 107 are exclusively confined to the American continent, 18 more are common to America and distant regions of the earth, one only is limited to tropical Asia, and two to tropical Africa, the remainder being scattered among remote islands – the Sandwich group, the Galapagos, Madagascar, and St. Helena.

8

In Nature for September 14, 1882.

9

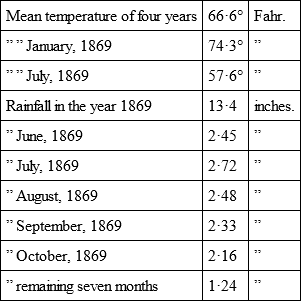

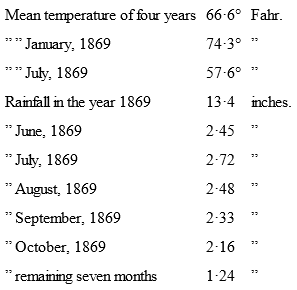

The only accurate information that I have found respecting the climate of Lima is contained in a paper by Rouand y Paz Soldan, “Resumen de las Observaciones Meteorologicas hechas en Lima durante 1869,” quoted in the French translation of Grisebach’s “Vegetation du Globe.” Reduced to English measures, they give the following results: —

There is reason to think that the temperature for July, 1869, given above was exceptionally low, and although the months during which fogs prevail are abnormally cool for a place within 13° of the equator, I believe that the thermometer rarely falls below 60° Fahr.

10

See Appendix A, On the Fall of Temperature in ascending to Heights above the Sea-level.

11

It is a curious illustration of the utterly untrustworthy character of statements made by unscientific travellers to read the following passage in a book published by a recent traveller in South America, who visited Chicla in November, the beginning of summer. He declares that the fringe of green vegetation “dwindles and withers at a height of nine or ten thousand feet;… while on the upper grounds, where sometimes rain is plentiful, the air is too keen and cold for even the most dwarfish and stunted vegetation to thrive.”

12

“Versuch einer Entwicklungsgeschichte der Pflanzenwelt.”

13

The heights are certainly incorrect. The base of the hill of Amancaes is nearly seven hundred feet above sea-level, and Mr. Nation states that the two localities mentioned by Mr. Cruikshank are at about the same elevation.

14

Two small Chilian wooden ships, the Esmeralda, of 850 tons, mounting eight guns, commanded by Arturo Prat, and the Covadonga, of 412 tons, with two guns, commanded by Condell, were engaged in the blockade of Iquique, when, on the 21st of May, 1879, they were attacked by the Peruvian ironclad Independencia, of 2004 tons, mounting 18 (chiefly heavy Armstrong) guns, commanded by J. G. Moore, and the monitor Huascar, of 1130 tons, mounting two 300-pounder Armstrong turret guns, besides two deck guns, under Miguel Grau, the most skilful and enterprising of the Peruvian commanders. The Chilian captains resolved on a desperate defence. After maintaining for two hours the fight against the Huascar, Arturo Prat resolved on the attempt to board his adversary. Bringing his ship alongside, he sprang on the deck of the Huascar; but the ships were separated at once, and two men only fell along with him, while the Esmeralda went to the bottom with her crew of 180 men, of whom several were picked up by the boats of the Huascar. The Independencia, following the little Covadonga, ran on the rocks in the shallows south of Iquique, and became a total wreck; while the Covadonga, though shattered by her enemy’s guns, was able to reach Autofogasta. The heroism of the Chilian commanders saved their country, and at the critical moment changed the fortune of the war.

15

In the preface to his “Florula Atacamensis,” Dr. Philippi, who has explored this region more thoroughly than any other traveller, states that on the range of coast hills between the Pan de Azucar (lat. 26° 8′ south) and Miguel Diaz (lat. 24° 36′) the fogs, called in Peru garua, or garruga, deposit during a great part of the year some moisture which occasionally takes the form of fine rain, such as is familiarly known to occur on the hills near Lima. He remarks as singular the fact that the same phenomenon is not observed on the coast north or south of those limits. From more recent observations, it would appear that this is not strictly true as regards the higher coast hills near Coquimbo, but it seems to hold as regards the tract of coast to the northward, between the neighbourhood of Taltal and that of Iquique, a distance of about four degrees of latitude. It may be that the coast hills are lower here than further south, and that as the desert region inland rises very gradually, and has a higher temperature inland than near the coast, the formation of fog is prevented. Whatever be the cause, the absence of fog would go far to account for the utter sterility of this region.

16

The four species of Encelia described in De Candolle’s “Prodromus” appear to me to be but slightly modified forms of a single species. Since the publication of that work, several other and quite distinct species have been ranked under the same generic name.

17

While botanizing in the Tajo de Ronda, the singular cleft which cuts through the rocky hill on which the town is built, I was once for some time in positive danger. The boys, having espied me, assembled on the bridge that crosses the cleft, some three hundred feet above my head, and commenced a regular fire of stones, that drove me to take shelter under an overhanging rock until, being tired of the sport, they turned their attentions elsewhere.

18

One of the difficulties felt by all students of geographical distribution arises from the imperfect or careless indications given both in books and in herbaria, and this is more felt in regard to South America than as to any other part of the world. A very large proportion of the earlier collections bear simply the label “Brazil,” forgetting that the area is as great as that of Europe. In other cases local names of places, not to be found on maps or in gazetteers, embarrass the student and weary his patience. It is mainly from Darwin that naturalists have learned that geographical distribution is the chief key to the past history of the earth.

19

The last season of excessive rainfall was that of 1877. I have seen no complete returns, but it appears that the rain of that year commenced in Central Chili in February, a very rare phenomenon; that more than six inches of rain fell in April, of which, at Santiago, four inches fell in twenty-four hours. More heavy rain fell in May, and finally in July a succession of storms flooded large districts, destroying property and life, the fall for the month being more than fourteen inches at Valparaiso. Much interesting information respecting the climate of Chili will be found in a work by Don B. Vicuña Mackenna, “Ensayo Historico sobre el Clima de Chile” (Valparaiso: 1877), from which I have borrowed the above-mentioned particulars.

20

I believe that in the column for rainfall at Punta Arenas, snow has not been taken into account.

21

The recent untimely death of this valuable official is deplored by all classes in Chili.

22

This is doubtless the summit described by Darwin under the name Campana de Quillota. He gives the height as 6400 feet above sea-level. The figures in the text are taken from the Chilian survey.

23

The mapping of the Andean chain is a task of immense difficulty, and although the Chilian survey is the best that has yet been executed, it leaves much to be desired. Even in the small district which I was able to visit, I found several grave errors in Petermann’s map, reduced from the Chilian survey, which is, nevertheless, the best that has been published in Europe. One of the most serious is the omission of the Uspallata Pass, the most frequented of those leading from Central Chili to the Argentine territory, which is neither named nor correctly indicated by the tints adopted to mark the zones of elevation.

24

“Origin of Species,” 3rd edit., p. 410.

25

Molina, one of the most pernicious blunderers who have brought confusion into natural history, grouped together under the generic name Peumus several Chilian plants having no natural connection with each other. Misled by his erroneous description, botanists have applied the name peumus to a fragrant shrub, common about Valparaiso and elsewhere, which is known in the country by the name boldu.

26

The Baths of Cauquenes are said to be 2523 feet above the sea; the Morro, by aneroid observation, is about 2000 feet higher.

27

As happens with many other plants described by early botanists, there has been much confusion in regard to the species named by Linnæus Lobelia Tupa. The plant was first made known to Europeans by the excellent traveller, Father Feuillée, whose “Journal des Observations Physiques Mathématiques et Botaniques faites sur les côtes de l’Amérique meridionale, etc.,” published in 1714, is a book which may still be consulted with advantage. His descriptions of plants are usually careful and accurate, but the accompanying plates all ill-executed and often misleading. Linnæus, followed by Willdenow, refers to Feuillée’s work, but gives a very brief descriptive phrase which suits equally well Feuillée’s plant and several others subsequently discovered. Aiton, in the “Hortus Kewensis,” gives the name Lobelia Tupa to a plant which is plentiful about Valparaiso, where I found it still in flower, the seeds of which were received at Kew about a century ago from Menzies. This is now generally known by the not very appropriate name Tupa salicifolia of Don, but was first published by Sims in the Botanical Magazine, No. 1325, as Lobelia gigantea, which name it should now bear. The plant which I found near Cauquenes appears to be the Tupa Berterii of Decaudolle, a rare species, apparently not known to the authors of the “Flora Chilena.” No doubt could have arisen as to the plant intended by Linnæus as Lobelia Tupa if writers had referred to Feuillée’s full and accurate description. His account of the poisonous effects of the plant was probably derived from the Indians, and may be exaggerated. The whole plant, he says, is most poisonous, the mere smell causing vomiting, and any one touching his eyes after handling the leaves is seized with blindness. I may remark that the latter statement, which appears highly improbable, receives some confirmation from the observations of Mr. Nation, mentioned above in page 77. The plant which I saw in Peru, but failed to collect, is much smaller than most of the Chilian species, and has purple flowers, but is nearly allied in structure. It is probably the Tupa secunda of Don. I gather from a passage in one of Mr. Philippi’s writings that the word tupa in Araucanian signifies poison. We are yet, I believe, ignorant of the chemical nature of the poisonous principle contained in the plants of this group.

28

The measurements of the height of the peak of Aconcagua vary considerably in amount, but I believe that the most reliable is that adopted by Petermann – 6834 metres, or 22,422 English feet.

29

The inconvenience of using a periphrasis for the name of so important a country may warrant my adoption of the obvious name Argentaria in place of Argentine territory, or Argentine Confederation, and I shall adhere to the shorter designation in the following pages.

30

It is quite possible that the bird which I took for the black albatross was the giant petrel, common, according to Darwin, in these waters, and closely resembling an albatross.

31

See an interesting paper in the Journal of Botany for July, 1884.