полная версия

полная версияNotes of a naturalist in South America

Having learned that the steamer had been detained by very heavy weather in the South Pacific, and had had great difficulty in making Cape Pillar, the western landmark of the Straits, I bade farewell to my kind host, and sought for quarters in the great floating hotel. There is something depressing in arriving in a place of entertainment on a cold night, when it is obvious that one’s appearance is neither expected nor desired. After a while a steward, scarcely half awake, made his appearance, and arranged my berth. I soon turned in, and slept until near nine o’clock, when we were already well on our way towards the Atlantic opening of the Straits. The morning was bright and not very cold, and for the first time since I entered this region the weather remained unchanged during the day, and the sky clear, with the exception of heavy banks of cloud which showed in the afternoon above the southern and western horizon.

In the morning, when about twenty miles north of Sandy Point, and nearly abreast of Peckett Harbour, the unmistakable peak of Mount Sarmiento was for a short time distinctly seen. It is needless to say that this was due to atmospheric refraction, for the distance was rather over a hundred English miles, and in a non-refracting atmosphere a mountain seven thousand feet high would be below the visible horizon at a distance of about eighty-five miles. Of Mount Darwin, which is believed to be the highest summit of the Fuegian Archipelago, I was not destined to see anything; it is probably completely concealed by the range which runs across the main island of Tierra del Fuego.

RE-ENTERING THE ATLANTIC.

The scenery of the eastern side of the Straits of Magellan offers little to attract the eye, the shores on both sides being low and little varied. From Cape Froward to Peckett Harbour the Patagonian coast runs nearly due north, and then trends east-north-east for about seventy miles, where the channel is contracted between the northern shore and Elizabeth Island. After passing the island, we entered the part called “The Narrows,” where the Fuegian coast approaches very near to the mainland of the continent. As the day was declining, we issued from this channel into a bay fully thirty miles wide, partly closed by two headlands, which are the landmarks for seamen entering the Straits from the Atlantic. That on the Fuegian side is Cape Espiritu Santo, and the bolder promontory on the northern side is the Cape Virgenes. To a detached rock below the headland English seamen have given the name Dungeness. In the failing light, I could see that the coast westward from Cape Virgenes rises into hills, which appeared to be bare of forest. I should guess their height not to exceed two thousand feet, if it even reaches that limit.

It was almost quite dark when we finally re-entered the Atlantic, and found its waters in a very gentle mood. In these latitudes the name Pacific is not well applied to any part of that which the older navigators more fittingly designated the Southern Ocean.

It was impossible to live for more than a week in winter, at the southern extremity of the American continent, without having one’s attention engaged by the singular features of the climate of this region, and especially by their bearing on wider questions which have of late years assumed fresh importance. Mainly through the writings of Dr. James Croll, and the remarkable ability and perseverance with which he has sustained his views, geologists and students of every other branch of natural science have learned to estimate the influence which the secular changes in the eccentricity of the earth’s orbit may have exercised on the physical condition of our planet. I have ventured, in the Appendix, to discuss some portions of the vast range of subjects treated of by Dr. Croll,35 and to state the reasons which force me to dissent from some of his conclusions; but I shall here merely say that the impressions derived from my own short experience have been confirmed by subsequent diligent inquiry, and especially by the writings of Dr. Julius Hann, most of which have been published since my return to England.

The belief that the mean temperature of the southern is considerably lower than that of the northern hemisphere was, until recently, prevalent among physical geographers, and has been assumed as an undoubted fact by Dr. Croll. He accounts for it by the predominance of warm ocean-currents that pass from the southern to the northern hemisphere within the tropics, and which, as he maintains, ultimately carry a great portion of the heat of the equatorial regions to the north Temperate and Frigid Zones. I think that this belief, as well as many others regarding physical geography, originated in the fact that physical science in its more exact form, had its birth in Western Europe, a region which, especially as to climate, is altogether exceptional in its character. The further our knowledge, yet too limited, has extended in the southern hemisphere the less ground we find for a belief in the supposed inferiority of its mean temperature. What we do find, in exact conformity with obvious physical principles, is that in the hemisphere where the water surface largely predominates over that of land, the temperature is much more uniform than where the land occupies the larger portion of the surface. In the former, the heat of summer is mainly expended in the work of converting water into vapour, and partially restored in winter in the conversion of vapour into water or ice.

TEMPERATURE OF SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE.

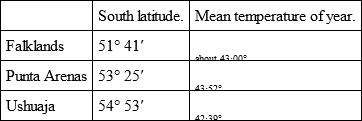

We unfortunately possess but three stations in the southern hemisphere, south of the fiftieth degree of latitude, from which meteorological observations are available, and these are all in the same vicinity – the Falkland Islands, Punta Arenas, and Ushuaja, the mission station in the Beagle Channel at the south side of the main island of Tierra del Fuego. The following table shows the mean temperature of the year at these stations in degrees of Fahrenheit’s scale.

If we compare these with the results of observations at places on the east side of continents in the northern hemisphere, we find the latter to show a very much more rigorous climate. Nikolaiewsk, near the mouth of the Amur, in lat. 52° 8′ north, has a mean annual temperature of 32·4° Fahr.; and at Hopedale, in Labrador, lat. 55° 35′, the mean is certainly not higher than 26° Fahr. Even in the island of Anticosti, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, lat. 49° 24′ north, the main yearly temperature is only 35·8°, or more than 70 below that of the Falkland Islands. But it may be truly said that, although the stations now under discussion are on the eastern side of the South American continent, they virtually enjoy an insular climate, and that there is probably little difference between their temperature and that of places on the west side of the Straits of Magellan.

On comparing the few places out of Europe from which we possess observations in high northern latitudes, I think that the station which admits of the fairest comparison is that of Unalaschka in the North Pacific. The observations at Illiluk in that island, in lat. 53° 53′ north, show a mean annual temperature of only 38·2° Fahr., while at Ushuaja, 1° farther from the equator, the mean temperature is higher by more that 4°. It is true that at Sitka, in lat. 57° north, we find a mean temperature of 43·28° Fahr., or about the same as that of the Falklands. But the position of Sitka is quite exceptional. It is completely removed from the influence of the cold currents that descend through Behring’s Straits, and a great mountain range protects it from northerly winds; south-westerly winds prevail throughout the year, and a very heavy rainfall, averaging annually eighty-one inches, imports to the air a large portion of heat derived from equatorial regions. On the coast of Western Patagonia and Southern Chili, this source of heat is partly counteracted by the cold antarctic current that sets along the western coast of South America.

VOYAGE TO MONTE VIDEO.

The general conclusion, which seems to be fully established, is that the southern hemisphere is not colder than the northern, and that all arguments based upon an opposite assumption must be set aside.

Among the passengers on board the Iberia were a large proportion of ladies and children, the families of English merchants settled in Chili. They had been miserable enough during the three or four days before entering the Straits. The weather had been very severe, and, large as is the vessel, heavy seas constantly broke over her upper deck, so that even the most adventurous were confined to the cabins, very many to their berths. The change to quiet waters and brighter skies acted like a charm, and the spirits of the passengers rose even more than the barometer. The children naturally became irrepressible, and left not a quiet corner in the whole ship. Having first invaded the smoking-cabin and made it the chief depôt for their toys and games, they next took possession of a small tent rigged up on the upper deck, to which the ejected smokers had retired. There are moments in such a voyage when one thinks that half a gale of wind with a cross sea would not be altogether unwelcome.

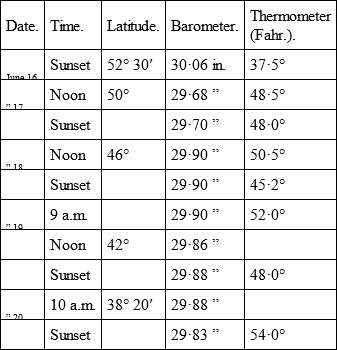

If such a perverse wish did arise in any breast, it was certainly disappointed. The voyage to Monte Video was uneventful, and offered little of special interest, but the weather was throughout fine. On the second day we met a slight breeze from the north, causing a decided rise of temperature and a fall of the barometer, but only a few drops of rain fell; and then, after returning to the normal temperature, the thermometer rose steadily as we advanced daily about four degrees of latitude. It may be worth while to give the following extract from my notes, observing that on board ship temperature observations are merely rough approximations. Those best admitting comparison are made about a quarter of an hour after sunset, the precise hour, of course, varying with the latitude, of which I give only a rough estimate.

Favoured by clear weather, we occasionally had glimpses of projecting headlands on the Patagonian coast, and especially on the 19th, when we made out the promontory of San José on the south side of the wide and deep Bay of San Matias, and later in the same day sighted some hills on the north side of the same gulf near the mouth of the Rio Colorado, the chief of Patagonian rivers.36 As far as I could discern, the sea-birds that approached the ship were the same species which had visited us on the Pacific coast, cape pigeons being as before the most numerous and persevering.

ESTUARY OF LA PLATA.

At sunrise on the shortest day we were approaching the city of Monte Video. Covering a hill some three hundred feet in height, and spreading along the shore at its base, the town presents a rather imposing aspect. It looks over the opening of the vast estuary of La Plata, fully sixty miles wide, into which the great rivers of the southern half of the continent discharge themselves. From the detritus borne down by these streams the vast plains that occupy the larger part of the Argentine territory have been formed in recent geological times, but the alluvial deposits have not yet filled up the gulf that receives the two great streams of the Paranà and the Uruguay. It would seem, however, that that consummation is rapidly approaching. Extensive banks, reaching nearly to the surface at low water, occupy large portions of the great estuary, and the navigable channel is so shallow that large ships are forced to anchor twelve or fourteen miles below Buenos Ayres, and even at Monte Video cannot approach nearer than two miles from the landing-place.

A small steam-tender came off to convey passengers to the city, and, with very little delay at the custom-house, I proceeded to the Hotel de la Paix, a French house, to which I was recommended. In spite of the irregularity of the ground, the city is laid out on the favourite Spanish chess-board plan, in quadras of nearly equal size. The main streets run parallel to the shore, and, being nearly level, are well supplied with tramcars; but the cross streets are mostly steep and badly paved. The flat roofs of the houses, enjoying a wide sea-view, are the favourite resort of the inmates in fine weather, and many of them have a mirador, roofed in and windowed on all sides, whence idle people may enjoy the view sheltered from sun or rain. A stranger is at once struck by one marked difference between the towns on the Atlantic coast and those on the western side of South America. Here people live free from the constant dread of earthquakes, and do not shrink from making their town houses as high as may be convenient; but the towns become more crowded, and one misses the charming patios of the better houses of Santiago and Lima.

To a traveller fresh from Peru and Chili and Western Patagonia, the region which I now entered, with its boundless spaces of plain and its huge rivers, appears by comparison tame and unattractive to the lover of nature. It is true that the industrial development of the last quarter of a century has been almost as rapid here as in the great republic of North America. The great plains are now traversed by numerous lines of railway, and steamers ply on the greater rivers and several of their tributaries. A naturalist may now accomplish in a few weeks, and at a trifling cost, expeditions that formerly demanded years of laborious travel. The southern slopes of the Bolivian Andes, stretching into the Argentine States of Salta, Oran, and Jujuy, are easily reached by the railway to Tucuman; and yet easier is the journey by the Paraguay river steamers that carry him over seventeen hundred miles of waterway to Cuyabà, in Central Brazil, the chief town of the great province of Matto Grosso. But the time at my disposal was strictly limited, and the coming glories of Brazil haunted my imagination, so that I had no difficulty in deciding to make but a brief halt in this part of the continent, limiting myself to a short excursion on the river Uruguay and a glimpse of Buenos Ayres.

CLIMATE OF URUGUAY.

Of three days passed at Monte Video a considerable portion was occupied by the English newspapers, full of intelligence of deep and chiefly of painful interest; but I twice had a pleasant walk in the country near the city. Some heavy rain had fallen before my arrival, and the roads, which are ill kept, were deep in mire; but the winter season in this region is very agreeable, and the favourable impression made during my short stay was confirmed by the general testimony of the residents as to the salubrity of the climate. The winter temperature is about the same as in the same latitude on the Chilian coast, but the summers are warmer by 9° or 10° Fahr., and the mean temperature of the year fully 5° higher, being here about 62° Fahr. We are, however, far removed from the great contrasts of temperature that are found on the eastern side of North America. At Monte Video the difference between the means of the hottest and coldest months is 22°, while in the same latitude on the coast of North Carolina the difference is fully 35°. On the whole, the climate most nearly resembles that of places on the coast of Algeria, especially that of Oran, save that in the latter place the winters are slightly colder and the summer months somewhat hotter.

The town is surrounded by country houses belonging to the merchants and other residents, each with a quinta (garden or pleasure-ground), in which a variety of subtropical plants seem to thrive. Comparatively few of the indigenous plants showed flower or fruit, certainly less than one is used to see in winter nearer home on the shores of the Mediterranean. But a small proportion of the ground is under tillage, and beyond the zone of houses and gardens one soon reaches the open country, which extends through nearly all the territory of the republic. The English residents have adopted the Spanish term (campo), which is universally applied in this region of America to the open country whereon cattle are pastured, and the stranger does not at first well understand the question when asked whether he is “going to the camp.”

The only fences used in a region where wood of every kind is scarce are posts about six feet high, connected by three or four strands of stout iron wire. These are set at distances of some miles apart, and serve to keep the cattle of each estancia from straying. It is said that when these fences were first introduced, many animals were killed or maimed by running at full speed against the iron wires, but that such cases have now become rare. The more intelligent or more cautious individuals avoided the danger, and have transmitted their qualities to a majority of their offspring.

At the hospitable table of the British minister, Mr. Monson, I met among other guests Mr. E – , one of the principal English merchants, whose kindness placed me under several obligations. On the following day he introduced me to an enterprising Italian, whose name deserves to be remembered in connection with modern exploration of the coasts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Signor Bartolomeo Bossi, who emigrated early in life to South America, seems to be a born explorer, and whenever he has laid by sufficient funds for the purpose he has forsaken other pursuits to start upon some expedition to new or little known parts of the continent. In a small steamer of 220 tons, fitted out at his own cost, he has in two expeditions minutely explored the intricate coasts of the Fuegian Archipelago and a great portion of the Channels of Patagonia.

SIGNOR BARTOLOMEO BOSSI.

Several of the discoveries interesting to navigators made in the course of the first of these voyages were published in the Noticias Hidrograficas of the Chilian naval department for 1876, and Signor Bossi asserts that the chief motive that determined the English admiralty in despatching the surveying expedition of the Alert was to verify the announcements first made by him. I have not seen any reference to Signor Bossi in the interesting volume, “The Cruise of the Alert,” by Dr. Coppinger; but it appears certain that many of the observations recorded in the Santiago Noticias have been accepted, and are embodied in the most recent charts.

In this part of America the Republic of Uruguay is commonly designated as the Banda Oriental, because it lies altogether on the eastern bank of that great river. It possesses great natural advantages – fine climate, sufficiently fertile soil, ready access by water to a vast region of the continent, along with a favourable position for intercourse with Europe. But these privileges are made almost valueless by human perversity. The military element, which has been allowed to dominate in the republic, is the constant source of social and political disorder. A stable administration is unknown, for each successful general who reaches the presidential chair must fail to satisfy all the greedy partisans who demand a share of the loaves and fishes. After a short time it becomes the turn of a rival, who, with loud promises of reform, and flights of patriotic rhetoric, raises the standard of revolt. If he can succeed in getting enough of the troops to join him, the revolution is made, and Uruguay has a new president, whose history will be a repetition of that of his predecessors. If the pretender should fail, he is summarily shot, unless he be fortunate enough to make his escape into the adjoining territories of Brazil or Argentaria.

On the day after my arrival the news of a rising headed by a popular colonel reached the capital, and troops were sent off in some haste to suppress the revolt. In each case the existence of the Government depends on the uncertain contingency whether the troops will remain faithful or will hearken to the fair promises of the new candidate for power.

It is obvious that a country in a chronic condition of disorder is a very inconvenient neighbour, and Uruguay would long have ceased to exist as a separate government, if it were not for the jealousy of the two powerful adjoining states. Brazil and Argentaria37 are each ready and willing to put down the enfant terrible, but neither would tolerate the annexation by its rival of such a desirable piece of territory. The prospect of a long and sanguinary war has hitherto withheld the Governments of Rio and Buenos Ayres, and secured, for a time, immunity to Uruguayan disorder.

NIGHT IN THE ESTUARY.

I had arranged to start on the 24th of June, in the steamer which plies between Monte Video and the Lower Uruguay. That day being one of the many festas that protect men of business in South America from the risk of overwork, banks and offices were closed, and but for the kindness of Mr. E – I should have found it difficult to carry out my plan. I went on board in the afternoon, and found a small crowded vessel, not promising much comfort to the passengers, but offering the additional prospect of safe guidance which every Briton finds on board a ship commanded by a fellow-countryman.

The sun set in a misty sky as we left our moorings and began to advance at half speed into the wide estuary of La Plata. As night fell the mist grew denser, and during the night and following morning we were immersed in a thick white fog. It was in reality a feat of seamanship that was accomplished by our captain. The great estuary of La Plata, gradually narrowing from about sixty miles opposite Monte Video to about sixteen at Buenos Ayres, is almost everywhere shallow and beset by sand or mudbanks, between which run the navigable channels. According to their draught, the ships that conduct the extensive trade between Buenos Ayres and Europe are spread over the space below the city, the larger being forced to anchor at a distance of fourteen miles. To avoid the banks, and to escape collision with the ships in the water-way, in the midst of a fog so dense was no easy matter. It is needless to say the utmost caution was observed. We crept on gently through the night, and at daybreak approached the anchorage of the large ships. Our captain seemed to be perfectly acquainted with the exact position of every one of them, and, as with increasing light he was able to recognize near objects, each in turn served as a buoy to mark out the true channel. Soon after sunrise we reached the moorings, about two miles from the landing-place, and lay there for a couple of hours, while the Buenos Ayres passengers and goods were conveyed to us in a steam-tender. It was a new experience to know one’s self so close to a great and famous city without the possibility of distinguishing any object.

At about ten a.m. we were again under steam and making for the mouth of the Uruguay on the northern side of the great estuary. The fog began to clear, and finally disappeared when, a little before noon, we were about to enter the waters of the mighty stream, which is, after all, no more than a tributary of the still mightier Paranà.38 Just at this point, signals and shouts from a very small steamer induced our captain to slacken speed. The strangers urgently appealed to him to take on board some cargo for a place on the river, the name of which escaped me. To this request a polite but very decided refusal was returned, the prudence of which we afterwards appreciated. The cargo in question doubtless consisted of arms, ammunition, or other stores for the use of the revolutionary force supposed to be gathered at Mercedes, not far from the junction of the Rio Negro with the Uruguay, and it clearly behoved the steamboat company to avoid being involved in such enterprises.

THE URUGUAY RIVER.

At its mouth the Uruguay has a width of several – probably seven or eight – miles, and at the confluence of the Rio Negro, some fifty miles up stream, the breadth must be nearly half as much. The water at this time was high, as heavy rain had fallen in the interior, and the current had a velocity of about three miles an hour. I believe that it is only exceptionally, during unusually dry seasons, that tidal water enters the channels of the Paranà or the Uruguay. I was struck by the frequent passage of large green masses of foliage that floated past as we ascended the river. Some consisted of entire trees or large boughs, but several others appeared to be formed altogether of masses of herbaceous vegetation twined together or adhering by the tangled roots. It can easily be imagined that, where portions of the bank have been undermined and fall into a stream, the soil is washed away from the roots, and the whole may be floated down the stream and even carried out to sea. The efficacy of this mode of transport as one of the means for the dispersion of plants is now generally recognized, and, considering that the basin of the Paranà covers a space of over twenty-one degrees of latitude, we must admit the probability that it has had a large part in the diffusion of many tropical and subtropical species to the southern part of the continent.