полная версия

полная версияIreland under the Tudors. Volume 3 (of 3)

London: Longmans & Co.

Edwd. Weller, lith.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

THE DESMOND REBELLION, 1579-1580

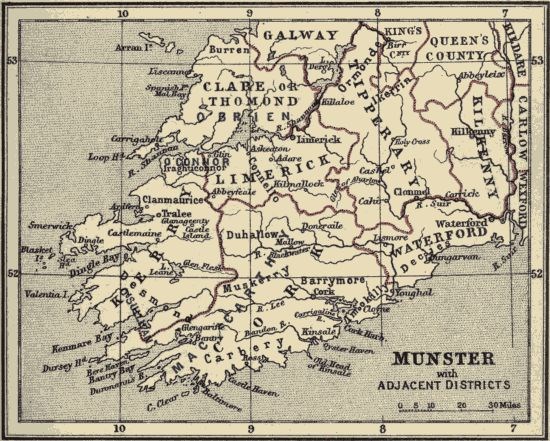

Vacillating policy of EnglandSir John of Desmond at once assumed the vacant command, and Drury warned the English Government that he was no contemptible enemy, though he had not Fitzmaurice’s power of exciting religious enthusiasm, and had yet to show that he had like skill in protracting a war. The Munster Lords were generally unsound, the means were wanting to withstand any fresh supply of foreigners, and there could be no safety till every spark of rebellion was extinguished. The changes of purpose at Court were indeed more than usually frequent and capricious. English statesmen, who were well informed about foreign intrigues, were always inclined to despise the diversion which Pope or Spaniard might attempt in Ireland; and the Netherlands were very expensive. Moreover, the Queen was amusing herself with Monsieur Simier. Walsingham, however, got leave to send some soldiers to Ireland, and provisions were ordered to be collected at Bristol and Barnstaple. Then came the news that Fitzmaurice had not above 200 or 300 men, and the shipping of stores was countermanded. On the arrival of letters from Ireland, the danger was seen to be greater, and Walsingham was constrained to acknowledge that foreign potentates were concerned, ‘notwithstanding our entertainment of marriage.’ One thousand men were ordered to be instantly raised in Wales, 300 to be got ready at Berwick, extraordinary posts were laid to Holyhead, Tavistock, and Bristol. Money and provisions were promised. Sir John Perrott received a commission, as admiral, to cruise off Ireland with five ships and 1,950 men, and to go against the Scilly pirates when he had nothing better to do. Then Fitzmaurice’s death was announced, and again the spirit of parsimony prevailed. The soldiers, who were actually on board, were ordered to disembark. These poor wretches, the paupers and vagrants of Somersetshire, and as such selected by the justices, had been more than a fortnight at Bristol, living on bare rations at sixpence a day, and Wallop with great difficulty procured an allowance of a halfpenny a mile to get them home. The troops despatched from Barnstaple were intercepted at Ilfracombe, and all the provisions collected were ordered to be dispersed. Then again the mood changed, and the Devonshire men were allowed to go.22

The Munster people sympathise with the rebellionDeath of Drury, who is succeeded by Sir William PelhamThe Earl of Kildare, who was probably anxious to avoid fresh suspicion, gave active help to the Irish government, ‘making,’ as Waterhouse testified, ‘no shew to pity names or kindred.’ He exerted his influence with the gentry of the Pale to provide for victualling the army, and he accompanied the Lord Justice in person on his journey to Munster. The Queen wrote him a special letter of thanks, and Drury declared that he found him constant and resolute to spend his life in the quarrel. The means at the Lord Justice’s disposal were scanty enough: – 400 foot, of which some were in garrison, and 200 horse. He himself was extremely ill, but struggled on from Limerick to Cork, and from Cork to Kilmallock, finding little help and much sullen opposition; but the arrival of Perrott, with four ships, at Baltimore seemed security enough against foreign reinforcements to the rebels, and Maltby prevented John of Desmond from communicating with Connaught. Sanders contrived to send letters, but one received by Ulick Burke was forwarded, after some delay, to the government, and Desmond still wavered, though the Doctor tried to persuade him that Fitzmaurice’s death was a provision of God for his fame. ‘That devilish traitor Sanders,’ wrote Chancellor Gerrard, ‘I hear – by examination of some persons who were in the forts with him and heard his four or five masses a day – that he persuaded all men that it is lawful to kill any English Protestants, and that he hath authority to warrant all such from the Pope, and absolution to all who can so draw blood; and how deeply this is rooted in the traitors’ hearts may appear by John of Desmond’s cruelty, hanging poor men of Chester, the best pilots in these parts, taken by James, and in hold with John, whom he so executed maintenant upon the understanding of James his death.’ No one, for love or money, would arrest Sanders, and Drury could only hope that the soldiers might take him by chance, or that ‘some false brother’ might betray him. Desmond came to the camp at Kilmallock, but would not, or could not, do any service. Drury had him arrested on suspicion, and, according to English accounts, he made great professions of loyalty before he was liberated. The Irish annalists say his professions were voluntary, that he was promised immunity for his territory in return, and that the bargain was broken by the English. Between the two versions it is impossible to decide. The Earl did accompany Drury on an expedition intended to drive John of Desmond out of the great wood on the borders of Cork and Limerick. At the place now called Springfield, the English were worsted in a chance encounter, their Connaught allies running away rather than fight against the Geraldines. In this inglorious fray fell two tried old captains and a lieutenant, who had fought in the Netherlands, and the total loss was considerable. Drury’s health broke down after this, and instead of scouring Aherlow Woods the stout old soldier was carried in a litter to his deathbed at Waterford. As he passed through Tipperary, Lady Desmond came to him and gave up her only son as a hostage – an unfortunate child who was destined to be the victim of state policy.

Sir William Pelham, another Suffolk man, had just arrived in Dublin, and was busy organising the defence of the Pale against possible inroads by the O’Neills. He was at once chosen Lord Justice of the Council, and the Queen confirmed their choice.

Drury was an able and honest, though severe governor, and deserves well of posterity for taking steps to preserve the records in Birmingham Tower. Sanders gave out that his death was a judgment for fighting against the Pope, forgetting that Protestants might use like reasoning about Fitzmaurice.23

Desmond still hesitatesMaltby was temporary Governor of Munster by virtue of Drury’s commission, and had about 150 horse and 900 foot, the latter consisting, in great measure, of recruits from Devonshire. He summoned Desmond to meet him at Limerick, and sent him a proclamation to publish against the rebels. The Earl would not come, and desired that freeholders and others attending him might be excepted from the proclamation. Maltby, who had won a battle in the meantime, then required him to give up Sanders, ‘that papistical arrogant traitor, that deceiveth the people with false lies,’ or to lodge him so that he might be surprised. Upon this the Earl merely marvelled that Maltby should spoil his poor tenants. ‘I wish to your lordship as well as you wish to me,’ was the Englishman’s retort, ’and for my being here, if it please your Lordship to come to me you shall know the cause.’ It did not please him, and the governor made no further attempt at conciliation.24

Maltby defeats the rebelsThe encounter which gave Maltby such confidence in negotiation took place on October 3 at Monasternenagh, an ancient Cistercian abbey on the Maigue. The ground was flat, and Sir William Stanley, the future traitor of Deventer, said the rebels came on as resolutely as the best soldiers in Europe. Sir John and Sir James of Desmond had over 2,000 men, of which 1,200 were choice gallowglasses, and Maltby had about 1,000. Desmond visited his brothers in the early morning, gave them his blessing, and then withdrew to Askeaton, leaving his men behind.

‘He is now,’ said Maltby, ‘so far in, that if her Majesty will take advantage of his doings his forfeited living will countervail her Highness’s charges; and Stanley remarked that the Queen might make instead of losing money by the rebellion. After a sharp fight, the Geraldines were worsted, and the Sheehy gallowglasses, which were Desmond’s chief strength, lost very heavily. The two brothers escaped by the speed of their horses and bore off the consecrated banner, ‘which I believe,’ said Maltby, ‘was anew scratched about the face, for they carried it through the woods and thorns in post haste.’ Sanders, if he was present, escaped, but his fellow-Jesuit, Allen, was killed. In a highly rhetorical passage Hooker describes this enthusiast’s proceedings, and likens his fall to that of the prophets of Baal. Maltby’s commission died with Drury, and he stood on the defensive as soon as he heard of the event.25

Desmond and OrmondeOrmonde had been about three years in England, looking after his own interests, and binding himself more closely to the party of whom Sussex was the head. Disturbance in Munster of course demanded his presence, and he prepared to start soon after the landing of James Fitzmaurice. ‘I pray you,’ he wrote to Walsingham, ‘do more in this my cause than you do for yourself, or else the world will go hard.’

Desmond is forced to say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’In thanking the Secretary for his good offices he said, ‘I am ready to serve the Queen with my wonted good-will. I hope she will not forget my honour in place of service, though she be careless of my commodity.’ A month later he was in Ireland, and after spending some days at Kilkenny, was present at the delivery of the sword to Pelham, whom he prepared to accompany to the south. He had the Queen’s commission as general in Munster, and Kildare was left to guard the Ulster border. Little knowing the man he had to deal with, Desmond wrote to bid him weigh his cause as his own. ‘Maltby,’ he said, ‘is a knave that hath no authority, who has been always an enemy to mine house.’ To some person at Court, perhaps to Sidney, he recounted his services. Before the landing of Fitzmaurice he had executed three scholars, of which one was known to be a bishop. He had at once given notice of the landing, had blockaded Smerwick, and had helped to drive off the O’Flaherties, so that the traitors had like to starve. After Fitzmaurice’s death he had broken down the fort and had been ready to victual Drury’s army, had not the latter prepared to support his men by spoiling the Desmond tenants. Finally, he had delivered his son, and would have done more, but that many of his men had deserted while he was under arrest. All along he had feared the fate of Davells for his wife and son, knowing that his brother John hated them mortally. Maltby had none the less treated him as an enemy, and had in particular ‘most maliciously defaced the old monument of my ancestors, fired both the abbey, the whole town, and all the corn thereabouts, and ceased not to shoot at my men within Askeaton Castle.’ The letters which Ormonde received from Desmond – for there seem to have been more than one – were handed over to Pelham, who directed the writer to meet him between Cashel and Limerick, or at least at the latter place. He was to lose no time, for the Lord Justice was determined not to lie idle. Desmond did not come, but he had an interview with Ormonde for the discussion of certain articles dictated by Pelham. The principal were that Desmond should surrender Sanders and other strangers, give up Carrigafoyle or Askeaton, repair to the Lord Justice, and prosecute his rebellious brother to the uttermost. The penalty for refusing these terms was that he should be proclaimed traitor. After conferring with Ormonde, he wrote to say that he had been arrested when he went to the late Lord Justice. He refused to give up Askeaton, perhaps thinking it impregnable, but was ready to do his best against Sanders and his unnatural brethren if his other castles were restored to him. Pelham answered that the proclamation was ready and should be published in three days, unless Desmond came sooner to his senses. Still protesting his loyalty, he refused to make any further concession. A last chance was given him; if he would repair to Pelham’s presence by eight next morning he should have licence to go to England. No answer was returned, and the proclamation was published as Pelham had promised. By a singular coincidence, and as if to presage the ruin of the house of Desmond, a great piece of the wall of Youghal fell of itself upon the same day. The die was cast, and the fate of the Geraldine power was sealed.26

Desmond is proclaimed traitor. November, 1579The proclamation asserted that Desmond had practised with foreign princes, that he had suffered Fitzmaurice and his Spaniards to lurk in his country, and that he had been privy to the murder of Davells and others. He was accused of feigning loyalty and of purposely allowing the garrison to escape from their untenable post at Smerwick. It was said that he had gone from the Lord Justice into Kerry against express orders, had seen that the strangers were well treated – being, in fact, in his pay – and had even placed some of them in charge of castles. He had joined himself openly with the proclaimed traitors his brothers, and with Dr. Sanders, that odious, unnatural, and pestiferous traitor; and quite lately his household servants had been engaged with the Queen’s troops at Rathkeale. Perhaps the strongest piece of evidence was a paper found in a portmanteau belonging to Dr. Allen, ‘one of the traitors lately slain,’ which showed how the artillery found at Smerwick had been distributed by Desmond among the rebels. To detach waverers it was announced that all who appeared unconditionally before the Lord Justice or the Earl of Ormonde should be received as liege subjects. Besides Pelham, Waterhouse, Maltby, and Patrick Dobbyn, Mayor of Waterford, the subscribers to the proclamation were all Butlers; Ormonde and his three brothers, Lords Mountgarret and Dunboyne, and Sir Theobald Butler of Cahir. Some of these had been rebels, but all were now united to overwhelm the Geraldines and possibly to win their lands. ‘There was,’ said Waterhouse, ‘great practice that the Earl of Ormonde should have dealt for a pacification, but when it came to the touch he dealt soundly – and will, I think, follow the prosecution with as much earnestness as any to whom it might have been committed.’ He was, in fact, enough of an Irishman to wish that even Desmond might have a last chance; but when it came to choosing between loyalty and rebellion his choice was as quickly made as his father’s had been when he resisted the blandishments of Silken Thomas.27

Weakness of the GovernmentThe Queen grumblesFinding himself in no condition to attack so strong a place as Askeaton, Pelham returned to Dublin, and Ormonde went to Waterford to prepare for a western campaign. He wrote to tell Walsingham of his vast expenses. His own company of 100 men was so well horsed and armed that none could gainsay it; but the ships were unvictualled, and Youghal and Kinsale were doubtfully loyal. ‘I have the name of 800 footmen left in all my charge, and they be not 600 able men, as Mr. Fenton can tell, for I caused my Lord Justice to take view of them. They be sickly, unapparelled, and almost utterly unvictualled. There are 150 horsemen with me that be not 100… My allowance is such as I am ashamed to write of… I long to be in service among the traitors, who hope for foreign power.’ But the Queen was very loth to spend money, and very angry at the imperfect intelligence from Ireland. The number of Spaniards who landed was never known. There were certainly more in the country than Fitzmaurice had at Smerwick; and the number of harbours between Kinsale and Tralee was most convenient for contraband cargoes. Her Majesty also grumbled about Pelham’s new knights, lest they should be emboldened to ‘crave support to maintain their degree.’ There were but two, Gerrard the Chancellor, and Vice-Treasurer Fitton; both had served long and well, and it was customary for every new governor to confer some honours. Peremptory orders were sent that the pension list should be cut down, and the Queen even talked of reducing the scanty garrison. She was offended at the proclamation of Desmond, as she had been five years before, and found fault with everything and everybody. Pelham said the proclamation was an absolute necessity, since no person of any consideration in Munster would stir a finger until ‘assured by this public act that your Majesty will deal thoroughly for his extirpation.’ Before the proclamation, at the time of the fight with Maltby, Desmond had guarded the Pope’s ensign with all his own servants, and ‘in all his skirmishes and outrages since the proclamation crieth Papa Aboo, which is the Pope above, even above you and your imperial crown.’ In despair the Lord Justice begged to be recalled, but Ormonde, who knew Elizabeth’s humour, made up his mind to do what he could with small means. At this juncture, and as if to show that he had not been proclaimed for nothing, Desmond committed an outrage which for ever deprived him of all hope of pardon.28

Desmond threatens YoughalSack of YoughalThe town of Youghal, which had always been under the influence of his family, was at this time fervently Catholic. The Jesuits kept a school there, and the townsmen had been ‘daily instructed in Christian doctrine, in the celebration of the Sacrament, and in good morals, as far as the time permitted, but not without hindrance.’ The corporation were uneasy, and sent two messengers, of which one was a priest, to fetch powder from Cork. Sir Warham St. Leger, who had been acting as Provost Marshal of Munster since Carter’s death, gave the powder or sent it, and offered to send one of Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s well-armed ships to protect the town, which the fallen wall laid open to attack. But the corporation refused to incur the expense of supporting Gilbert’s sailors or Ormonde’s soldiers, and made little or no preparation for their own defence. On Friday, November 13, Desmond, accompanied by the Seneschal of Imokilly, encamped on the south side of Youghal, near the Franciscan priory, which his own ancestors had founded. He gave out that his intentions were harmless, and that he had come only to send messengers to Ormonde, who could prove that he had been wrongfully proclaimed traitor. Meanwhile, he demanded wine for his men, and the mayor, who was either a fool or a traitor, let him take the ferry-boat, which was the only means by which the town might be relieved from the Waterford side. The Geraldines were to take two tuns of wine, and then depart; but during Saturday and Sunday morning they had frequent conversations with their friends on the walls. The result was that they mustered with evidently hostile intentions, and that the mayor ordered the gunners in the round tower, which commanded the landing-place, not to fire first, although they had a ‘saker charged with a round shot, a square shot, and a handspike of an ell long, wherewith they were like to have spoiled many of them. One elderly man of the town commanded not to shoot off lest the rebels would be angry therewith, and threatened to kill the gunner if he would give fire.’ Other sympathisers had already carried out ladders and hung ropes over the walls. With such help the rebels easily entered the breach, and in an hour all was over. Wives and maidens were ravished, and the town was ruthlessly sacked. Many of the inhabitants helped the work, ‘notwithstanding that they saw the ravishing of their women, the spoiling of their goods and burning of their houses, and that (which is most detestable treason), notwithstanding that they saw the Earl and Sir John, the Seneschal of Imokilly, and divers others draw down in the court-house of the town her Majesty’s arms, and most despitefully with their daggers to cut it and thrust it through.’ ‘This they did,’ Ormonde added, ‘as an argument of their cankered and alienated hearts.’ The plunder was considerable, and the Four Masters sympathetically record that many a poor indigent person became rich and affluent by the spoils of this town. Some of Lord Barry’s men were present, and most of the plunder was carried into his country and sold there. As one of Desmond’s followers filled his pouch with gold and silver from a broken chest, he said to his master that the thing was very pleasant if not a dream. Dermot O’Sullivan, the historian’s father, stood by and warned the Earl that the sweetest dreams might be but a mockery. The houses and gates were burned, and when Ormonde came a few weeks later he found the ruins in sole possession of a friar, who was spared for his humanity in securing Christian burial to Henry Davells. The mayor was caught and hanged at his own door, and it is hard to say that he did not deserve it.29

Ormonde’s revengeThe garrisonsA fortnight after the sack of Youghal, Ormonde was in the field, and thus describes the nature of his three weeks’ campaign: ‘I was in Connello the 6th of this month, between Askeaton and Newcastle, two of the Earl’s chief houses, and preyed, spoiled, and burned the country, even to the mountain of Slieve Logher, and returned to Adare without sight of the rebels. In the county of Cork I burned John of Desmond’s town and castle called Lisfinnen, with all his land in Coshbride.’ He then returned to Tipperary, and let his officers go to Dublin for a holiday. The soldiers had had bread only for one day out of four, and neither wine, beer, nor spirits. Beef and forage were scarce, and they had passed rivers, wading to the stomach, often seven times a day, and never less than three. They had to bivouack in the open, and camp-fires were hard to light in December. ‘It is easier,’ said Wallop, ‘to talk at home of Irish wars than to be in them.’ The garrisons had not a very pleasant time of it either. Sir George Bourchier was at Kilmallock with 200 men whose pay was two months in arrear. He had but fifty pounds of powder, and was unable to join Ormonde, for the chief magistrate locked the gates, and the inhabitants declared that they would vacate the town if he deserted them. Desmond was expected daily, and the fate of Youghal was before their eyes. Sir William Stanley and George Carew had been left by Maltby at Adare. Between them and Askeaton lay Kerry, which Sanders, in the Pope’s name, had granted to Sir James of Desmond. One morning early Stanley and Carew passed 120 of their men over the Maigue in one of the small boats, then and now called cots, which scarcely held ten at a time. After spoiling the country and putting to the sword whomsoever they thought good, they were attacked by Sir James, the knight of Glin, and the Spaniards who garrisoned Balliloghan Castle. Though the enemy were nearly four to one, Stanley and Carew managed to keep them in check till they reached the river, and then passed all their men over without loss, they themselves being the last to cross. It may be supposed, though Hooker does not say so, that they were in some measure covered by the guns of the castle. A little later Desmond tried to lure the garrison out by driving cattle under their walls, failing which ‘he sent a fair young harlot as a present to the constable, by whose means he hoped to get the house; but the constable, learning from whence she came, threw her (as is reported to me), with a stone about her neck, into the river.’30

Rumours from abroadOrmonde’s troublesThe English Government urged Pelham to go to Munster himself, and he waited for provisions at Waterford. Reports of the rebels’ successes came to England constantly from Paris, for the war had become a religious one. By every ship sailing to France or Spain, ‘Sanders,’ said Burghley, ‘sent false libels of the strength of his partners, and of the weakness of the Queen’s part.’ He spread rumours through Ireland that a great fleet was coming from Spain and Italy, bringing infinite stores of wine, corn, rice, and oil from the Pope and King Philip. Munster was to be Desmond’s; Ulster Tirlogh Luineach’s, and a nuncio was soon to come with full powers. It was reported that Desmond and Sanders distrusted each other, and that the latter was watched lest he should try to escape. His credit was probably restored by the arrival of two Spanish frigates at Dingle. It had been reported in Spain that both Desmond and Sanders were killed, but after conferring with the doctor, and learning that the rebellion was not yet crushed, the strangers promised help before the end of May. Sanders pleaded hard for St. Patrick’s day, lamenting that he had been made ‘an instrument to promise to perfect Christians what should not be performed.’ Still, through the spring and summer he confidently declared that help was coming, and in the meantime both he and Desmond were hunted like partridges upon the mountains. Pelham begged the Queen to consider what her position would have been had a stronger force landed with James Fitzmaurice, and to harden her heart to spend the necessary money. Ormonde was still more outspoken, and we know from others that his complaints were well founded. ‘I required,’ he said, ‘to be victualled, that I might bestow the captains and soldiers under my leading in such places as I knew to be fitted for the service, and most among the rebels. I was answered there was none. I required the ordnance for batteries many times and could have none, nor cannot as yet, for my Lord Justice sayeth to me, it is not in the land. Money I required for the army to supply necessary wants, and could have but 200l., a bare proportion for to leave with an army. Now what any man can do with these wants I leave to your judgment. I hear the Queen mislikes that her service has gone no faster forward, but she suffereth all things needful to be supplied, to want. I would to God I could feed soldiers with the air, and throw down castles with my breath, and furnish naked men with a wish, and if these things might be done the service should on as fast as her Highness would have it. This is the second time that I have been suffered to want all these things, having the like charge that now I have, but there shall not be a third; for I protest I will sooner be committed as a prisoner by the heels than to be thus dealt with again; taking charge of service upon me. I am also beholding to some small friends that make (as I understand) the Queen mislike of me for the spoil of Youghal, who most traitorously have played the villains, as by their own examination appeareth, an abstract of which I send to the Council, with letters written by the Earl of Desmond and his brethren to procure rebellion. There be here can write lies, as in writing Kilkenny was burned, before which, though it be a poor weak town, the rebels never came. They bragged they would spoil my country, but I hope if they do they will pay better for it than I did at the burning of theirs.’31