полная версия

полная версияSkinner's Dress Suit

Skinner knew enough about women not to warn Honey against talking confidentially with Mrs. McLaughlin, since this would excite her suspicions and recoil upon him, Skinner, with a shower of inconvenient questions. The only thing he could do, then, was to see to it that he and Honey should avoid places where the McLaughlins were liable to be. Skinner had been put to all sorts of devices to find out if the McLaughlins were going to certain parties to which he and Honey had been invited. He could n't do this very well by discussing the thing with the boss. So he had endeavored to determine the exact social status of the McLaughlins in that community and avoid the stratum in which they might circulate.

But this rule had failed him once or twice, for in communities of the description of Meadeville social life was more or less democratic and nondescript. When he had thought himself secure on certain occasions, he had bumped right into the McLaughlins and then it behooved him to stick pretty close to Honey all the evening.

This was not what he counted on, for Skinner was beginning to enjoy the sweets of broader social intercourse. He was beginning to like to talk with and dance with other women.

At times, when Skinner had received information at the last moment that the McLaughlins were to be at a party, he had affected a headache. On one of these occasions, Honey had set her heart on going and told Skinner that the Lewises had offered to take her along with them in case he should be delayed at the office – for Skinner had even pretended once or twice to be thus delayed. Presto! at Honey's words about the Lewises, Dearie's headache had disappeared.

Skinner thought with a humorous chuckle how Honey had said, "Dearie, I believe you're jealous of Tom Lewis."

"Perhaps I am," the miserable Skinner had admitted.

Skinner pictured the effect of exposure in all sorts of dramatic ways. But not once did he see himself suffering – only Honey. That's what worried him. He could bear pain without flinching, but he could not bear seeing other persons bear pain – particularly Honey. He knew he could throw himself on her mercy and confess and that she would forgive him because she'd know he did it on her account. But the hurt, the real hurt, would be hers to bear – and Skinner loved Honey.

Whenever Skinner had felt apprehensive or blue because of his self-promotion and the consequent difficulties he found himself plunged into, he had looked at his little book, and the credit side of the dress-suit account had always cheered him. But this infallible method was not infallible to-night. Going out on the train Skinner had the "blues" and "had them good." Gloom was closing in on all sides; he could n't tell why, unless the growing fear of exposure to Honey was taking hold on his subconsciousness and manifesting itself in chronic, indefinite apprehension.

At Meadeville, he purposely avoided Black, his next-door neighbor, with whom he customarily walked home from the depot – for Skinner was not the man to inflict an uncordial condition upon an innocent person.

When Skinner reached home, Honey drew him gently into the dining-room and pointed to the table. As she began, "Look, Dearie, oysters, and later – beefsteak! Think of it! Beefsteak!" – the now familiar formula that had come to portend some new extravagance, – Dearie stopped her.

"Don't, Honey, don't tell me what you've got for dinner, course by course. Give me the whole thing at once, or give me a series of surprises as dinner develops."

"I think you're horrid to stop me," Honey pouted reproachfully. "If I tell you what I 've got, you'll enjoy it twice as much – once in anticipation, once in realization."

"But what does this wonderful layout portend or promise?"

"To do good is a privilege, is n't it?"

"Granted."

"Then it's a promise," was Honey's cryptic answer.

Honey had certain little obstinacies, one of which was a way of teasing Dearie by making him wait when he wanted to know a thing. It was no use – Skinner could n't budge her.

"I'll wait," said he.

But all the circumstances pointed to the probability of a new "touch," which did not add greatly to his appetite.

After his demi-tasse, Skinner said to Honey, "Come, Honey, spring it."

"Not till you 've got your cigar. I want you to be perfectly comfortable."

Skinner lighted up, leaned back in his chair, and affected – so far as he was able – the appearance of indulgent nonchalance.

"Shoot."

Honey leaned her elbows on the table, rested her chin in the little basket formed by her interlacing fingers, and looked at Dearie in a way that she knew to be particularly engaging and effective.

"I 've always wanted to do a certain thing," she began. "You have always been my first concern, but now – I want to do something very personal – very much for my own pleasure. Will you promise to let me do it?"

"You bet I will," said Skinner; "nothing's too good for you!"

Skinner was genuinely and enthusiastically generous. Also, it would be a good scheme to indulge Honey, since he might have to ask her indulgence later on.

"I had a letter from mother this morning."

"Indeed?" There was little warmth in Skinner's tone. "I suppose she spoke pleasantly, not to say flatteringly, of me."

"Now, Dearie, don't talk that way. I know mother is perfectly unreasonable about you."

"She came darned near making me lose you. That's the only thing I've got against her."

"She has n't really anything against you – she only thinks she has," observed Honey.

"The only thing she's got against me is that she acted contrary to my advice and lost her money. She's hated me ever since!"

"It is wrong of her, but we 're not any of us infallible. Besides, she's my mother – and I can't help worrying about her."

"Why worry?"

"The interest on her mortgage comes due and she can't pay it."

"If she'd only listened to me and not taken the advice of that scalawag brother-in-law of yours, she would n't have any mortgage to pay interest on."

"She only got a thousand dollars. At five per cent, that's fifty dollars a year."

Skinner swallowed hard to keep down the savage impulse that threatened to manifest itself in profanity whenever he thought of Honey's mother and his weakling brother-in-law.

"Honey," he said grimly, "does your mother in that letter ask you to help her out with that interest?"

Honey lifted her head proudly. "She does n't ask me anything. She does n't have to. She only tells me about it."

"Yes, she does n't have to."

"You know I 've always wanted to do something for her, and I've never been able to. I'm ashamed to neglect her now, when we're living so well and dressing so well – and you have your raise. It's only a dollar a week."

"Have you any more relatives who have a speculative tendency?" Skinner began with chill dignity.

"Now, Dearie!" Honey began to cry and Skinner got up from the table and went over and kissed her.

She had married him against mother's advice and had stood by him like a brick, and he'd do anything for her. He stroked her glossy hair. "You have always wanted to do something for her, have n't you? You're a good girl! Do it! Send her a dollar a week!"

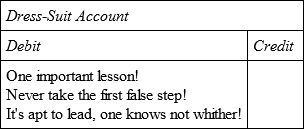

Skinner resumed his place at the table. This was the climax, he thought, the ne plus ultra of it all! He was to contribute a dollar a week to his mother-in-law to make up a loss caused by the advice of a detested, silly-ass brother-in-law, who had always hated him, Skinner. Surely, the dress-suit account had reached the debt limit! He took out his little book and jotted down: —

"You don't know how happy you've made me," said Honey, "and I 'm so proud of you – such strength of character – just like old Solon Wright, you're doing this for one you positively dislike, Dearie! – moral discipline!"

"Moral discipline, your grandmother!" snapped Skinner; then softly, "I'm doing it for one I love."

"I would n't have mentioned it if you hadn't got your raise. You know that!"

His raise! Skinner thought much about "his" raise as he lay in bed that night. Had he gone too far to back out, he wondered? By Jove, if he did n't back out, his fast-diminishing bank account would back him out! The thing would work automatically. Probably in his whole life Skinner had never suffered so much disgust. Think of it! He must go on paying mother-in-law a dollar a week forever and ever, amen! No, he'd be hanged if he'd do it! He'd tell Honey the whole thing in the morning and throw himself on her mercy. The resolution gave him relief and he went to asleep.

But he did n't tell Honey in the morning. He was afraid to hurt her. He thought of his resolution of the night. It's so easy to make conscience-mollifying resolves in the night when darkness and silence make cowards of us. No, he could n't tell her now. He'd tell her when he got home to dinner.

Meantime, things were doing in the private office of McLaughlin & Perkins, Inc.

"I've thought it over this far, Perk," said McLaughlin.

"Well?"

"Understand, I believe in Skinner absolutely – but – "

"Even your judgment is not infallible, you mean?"

"Exactly."

"So do I believe in him," Perkins said.

"I couldn't offend him for the world," McLaughlin went on. "He's as sensitive as a cat's tail. I would n't even dare to go into that cage of his." McLaughlin paused, "Yet we've got to do something. We can't wait till summer when he goes on his vacation. All kinds of things might happen before then. Time and Wall Street don't wait for anybody – except magnates!"

"You mean, have an expert accountant go over his books?" said Perkins.

"Certainly, that's what I mean – that's what you mean – that's what's been in both our minds from the time he began to travel with that Pullman crowd."

"It ought to be done at once," said Perkins. "If things are not regular – well, we must protect ourselves. I'm puzzled how to get rid of him while we're doing it. It's a delicate business," Perkins urged.

"I've got that all figured out, Perk." McLaughlin paused to register the comedy line that was to follow. "I'm going to send Skinner to St. Paul – after Willard Jackson!"

The partners were silent for a few moments; then Perkins said, "You can't, Mac."

"Why not?"

"It's a joke!"

"Of course it's a joke! But it's a harmless joke. You and I are the only ones that are 'on.' Skinner won't suspect. We'll put it up to him in dead earnest."

"The worst Jackson can do is to insult him the way he did you," said Perkins.

"The old dog!" said McLaughlin. He paused. "We'll get Skinner out of his cage for a while. It'll cost us so much money – we'll add that on to the expert accountant's bill. Can you think of a better way, Perk?"

"Mac, you're a genius!"

McLaughlin pressed the button marked "cashier."

Perkins put out his hand. "Don't call him yet, Mac. Wait till I get through laughing."

McLaughlin turned as the "cage man" entered.

"Hello, Skinner. Sit down." He paused a moment to register his next words. "Skinner, Mr. Perkins and I want you to do something for us."

Skinner looked from one partner to the other. "Yes," he said quietly.

"Two years ago we lost the biggest customer we ever had," McLaughlin proceeded.

"I know. Willard Jackson – St. Paul."

"Lost him through the stupidity of Briggs," snapped McLaughlin.

Skinner nodded.

"We've been trying to get him back ever since, as you know. We sent our silver-tongued Browning out there. No good! Then Mr. Perkins went out. Then I went out. All this you know."

The "cage man" nodded.

McLaughlin paused. "Skinner, we want you to go out to St. Paul and get him back."

Skinner looked curiously from one partner to the other, but both seemed to be dead serious.

"But – I'm – I'm not a salesman," the "cage man" stammered.

"That's just it," said McLaughlin earnestly. "There must be something wrong with the policy or the method or the manners of our salesmen, and Mr. Perkins and I have thought about it till we're stale. We want to put a fresh mind on the job."

"Jackson's gone over to the Starr-Bacon folks. They do well by him. How am I going to pry him loose?" said Skinner.

"We'll do even better by him," said McLaughlin. "You know this business as well as I do, Skinner. I 'm darned if I don't think you know it better. You know how closely we can shave figures with our competitors, I don't care who they are. I 'm going to make you our minister plenipotentiary. Do as you please, only get Jackson. I don't care if you take a small loss. We can make it up later. But we want his business."

Skinner pondered a moment. "Really, Mr. McLaughlin, I don't know what to say. I'm very grateful to you for such confidence. I 'll do my best, sir."

"It'll take rare diplomacy, rare diplomacy, Skinner," McLaughlin warned.

"What kind of a man is Mr. Jackson?" Skinner asked presently. "I know him by his letters, but what kind of man is he to meet?"

"The worst curmudgeon west of Pittsburg," said McLaughlin. "He'll insult you, he'll abuse you, he might even threaten to assault you like he did me. But he's got a bank roll as big as Vesuvius – and you know what his business means to us. Take as much time as you like, spend as much money as you like, Skinner, – don't stint yourself, – but get Jackson!"

"Have you any suggestions?" said Skinner.

"Not one – and if I had, I would n't offer it. I want you to use your wits in your own way, unhampered, unencumbered. It's up to you."

"When do you want me to go?"

"Business is business – the sooner the quicker!"

Skinner thought a moment. "Let's see – to-morrow's Sunday. I'll start Monday morning, if that is satisfactory."

"Fine!" said McLaughlin, rising and shaking hands with his cashier.

Skinner walked to the door, paused, then came halfway back. "What kind of a woman is Mrs. Jackson, Mr. McLaughlin?"

"Well," said McLaughlin, staggered by the question, "she don't handsome much and she ain't very young, if that's what you mean."

Skinner blushed. "I didn't mean it that way."

"The only thing I've got against Mrs. Jackson is she's a social climber," Perkins broke in.

"The only thing I 've got against her," said McLaughlin, "is – she don't climb. She wants to, but she don't."

"Is there any particular reason why she does n't climb?" said Skinner.

"Vulgar – ostentatiously vulgar," said McLaughlin.

Skinner smiled. He pondered a moment, then ventured, "Say, Mr. McLaughlin, it'd be a big feather in my cap if I landed Jackson, wouldn't it?"

"One of the ostrich variety, my son, – seeing that the great auk is dead," said McLaughlin solemnly.

Skinner's voice faltered a bit. "You don't know, Mr. McLaughlin, and you, Mr. Perkins, how grateful I am for this opportunity. I – I – " He turned and left the room.

"It's pathetic, ain't it? I feel like a sneak, Perk," said McLaughlin.

"Pathetic, yes," said Perkins. "But it's for his good. If he's all right, we're vindicating him – if he is n't all right, we want to know it."

The "cage man" whistled softly to himself as he reflected that the awful day of confessing to Honey was deferred for an indefinite period. It was a respite. But what gave him profound satisfaction was the fact that McLaughlin and Perkins were beginning to realize that he could do something besides stand in a cage and count money. They had made him their plenipotentiary, McLaughlin said. Gad! That meant full power! By jingo! He kept on whistling, which was significant, for Skinner rarely whistled.

And for the first time in his career, when he smelt burning wood pulp and looked down at the line of messenger boys with a ready-made frown and caught the eyes of Mickey, the "littlest," smiling impudently at him, Skinner smiled back.

For the rest of the day, as Skinner sat in his cage, three things kept running through his head: he's a curmudgeon; she's a climber; and she doesn't climb. From these three things the "cage man" subconsciously evolved a proposition: —

Three persons would go to St. Paul, named in order of their importance: First, Skinner's dress suit; second, Honey; and third, Skinner.

CHAPTER IX

SKINNER FISHES WITH A DIPLOMATIC HOOK

The first step in the scheme which Skinner had evolved for the reclamation of Willard Jackson, of St. Paul, Minnesota, was to be taken Sunday morning, after services, at the First Presbyterian Church of Meadeville, New Jersey.

Skinner had not told Honey he was going to take her on his trip West. He would do that after church, if a certain important detail of his plan did not miscarry. Although he paid respectful attention to the sermon, Skinner's thoughts were at work on something not religious, and he was relieved when the doxology was finished and the blessing asked. Unlike most of the others present, Skinner was in no hurry to leave. Instead, he loitered in the aisle until Mrs. Stephen Colby overtook him on her way down from one of the front pews.

"Why, Mr. Skinner, this is a surprise," exclaimed the social arbiter. Then slyly, "There's some hope for you yet."

"I thought I'd come in and make my peace before embarking on a railroad journey," Skinner observed.

"Going away? Not for long, I hope."

"St. Paul. I'm not carrying a message from the Ephesians – just a business trip."

"St. Paul's very interesting."

"I'm glad to hear it."

"You've never been there?"

"No."

"Goodness – I know it well."

"What bothers me is, I'm afraid Mrs. Skinner 'll find it dull. I'm taking her along. You see, I 'll have lots to do, but she does n't know anybody out there."

The social arbiter pondered a moment. "But she should know somebody. Would you mind if I gave her a letter to Mrs. J. Matthews Wilkinson? Very old friend of mine and very dear. You'll find her charming. Something of a bore on family. Her great-grandfather was a kind of land baron out that way."

"It's mighty good of you to do that for Mrs. Skinner."

"Bless you, I'm doing it for you, too. You have n't forgotten that you're a devilish good dancer and you don't chatter all the time?" Then, after a pause, "I'm wishing a good thing on the Wilkinsons, too," – confidentially, – "for I don't mind telling you I've found Mrs. Skinner perfectly delightful. She's a positive joy to me."

"You're all right, Mrs. Colby."

"That's the talk. Yes, I'm coming along." She waved her hand to Stephen Colby. "When do you go?"

"To-morrow morning."

"I'll send the letter over this afternoon – and if you don't mind, I 'll wire the Wilkinsons that you're coming on."

Skinner impulsively caught her hand. "Mrs. Colby, you're the best fellow I ever met!"

When the letter arrived at the Skinner's house that afternoon, Honey knitted her brows.

"I don't understand it."

"You ought to. It's for you."

"Dearie," said Honey, rising, her eyes brimming, "you mean to say that I'm going to St. Paul with you?"

"Don't have to say it. Is n't that letter enough?"

"Dearie, you're the most wonderful man I ever saw. Think of it! – a letter from Mrs. Colby! I'll bet those Wilkinsons are swells!"

"They breathe the Colby stratum of the atmosphere. It's a special stratum, designed and created for that select class."

"It's quite intoxicating."

"Special brands usually are."

"I thought those Western cities did n't have classes."

"My dear, blood is n't a matter of geography. There's not a village in the United States that does n't have its classes. The more loudly they brag of their democracy, the greater the distance from the top to the bottom."

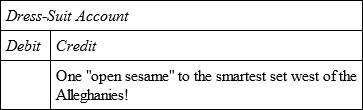

As Skinner said this, he jotted down in his little book: —

and Honey clapped her hands.

And as he put Mrs. Colby's letter in his inside pocket, Skinner muttered to himself, "A climber, but does n't climb. She'll climb for this all right!"

The Skinners reached St. Paul Tuesday night and registered at The Hotel. When he had deposited Honey in the suite which had been reserved by wire for them, Skinner proceeded to execute the next step in his scheme for the reclamation of Willard Jackson. He returned to the desk.

"I wish," he said to the chief clerk, "that you 'd see to it that a paragraph regarding my arrival is put in the morning papers, just a little more than mere mention among hotel arrivals" – he took pen and paper and wrote – "something like this: 'William Manning Skinner, of McLaughlin & Perkins, Inc., New York, reached town last evening and is stopping at The Hotel.' There's a lot of people here I want to see, but I might overlook 'em in the rush of business. If they know I'm here, they'll come to see me."

"Very good, Mr. Skinner," said the clerk. "I'll see to it."

Skinner paused a moment. "By Jove, I've almost forgotten the principal thing." He added a few words to the copy. "Put that in, too, please. Can you read it? See: 'Mrs. Skinner, daughter of the late Archibald Rutherford, of Hastings-on-the-Hudson, accompanies her husband.' That's just to please her."

"'Rutherford' – 'Hastings-on-the-Hudson' – swagger name," commented the clerk.

Skinner smiled at the clerk's comment. If it impressed this dapper, matter-of-fact, know-everybody man-of-affairs that way, how much more would it appeal to Mrs. Curmudgeon W. Jackson's social nose. Veritably, it augured well for his scheme.

But he only said, "It reads a devilish sight better than plain Skinner, does n't it?"

"Well," said the clerk, trying to be consoling and diplomatic and failing in both, "you must n't always judge a man by his name."

After breakfast next morning Skinner and Honey remained in their rooms, waiting for the message that was to come from the Wilkinsons, for Skinner had reckoned that any friend of the Colbys would receive prompt attention.

"She'll call you up, Honey, and ask us to dine to-night. There, there, don't ask any questions. I've figured it all out. But we're engaged until Saturday."

"Engaged every night? Why, Dearie, this is only Wednesday. You had n't told me anything about it."

"Quite right," said Skinner, "I had not."

"What are we going to do?"

"I have no plans. I suppose we'll sit in our rooms or go to the theater."

"Well," said Honey, "it beats me."

On reading the morning paper, Mrs. J. Matthews Wilkinson said to her husband, "They're here – the Skinners – Jennie Colby's friends, you know. We must have them to dinner."

"When?" said Wilkinson, looking up from his paper.

"I dare say they'll be here but a short time. Better make it to-night."

"You're the doctor," said Wilkinson, resuming his paper.

"We'll send out a hurry call for the Armitages and the Bairds and the Wendells," said Mrs. Wilkinson, mentally running over her list of the most select of St. Paul's inner circle. "We'll show these people that we're not barbarians out here."

"Can you corral all those folks for to-night? Is n't it rather sudden, my dear?"

"I've dined with them on shorter notice than that, just to accommodate them. I 'll call up the Skinners right away."

Honey answered the 'phone. Of course they'd be delighted to dine at the Wilkinsons, but every night was filled up to Saturday. A pause. Hold Saturday for them? She should say they would.

There was another pause. Then Honey clapped her hand over the receiver and turned to Skinner.

"Can we take a spin with them this afternoon, Dearie?"

"You bet. We've nothing else to do."

"You fraud," said Honey, when she had hung up the receiver, "you said you had engagements."

"I tried to convey to you," observed Skinner, somewhat loftily, "that we couldn't dine at the Wilkinsons' before Saturday. That covers it, I think."

According to Skinner's plans, the dinner at the Wilkinsons' was to be the big, climactic drive at the fortress of Willard Jackson's stubbornness.

As Skinner had reckoned, Mrs. Curmudgeon W. Jackson nosed out the paragraph in the morning paper, first thing.

"Who is this Mr. Skinner, Willard? Do you know him?"