полная версия

полная версияA Book of North Wales

In 1818, at the Flintshire Great Sessions, the “priest” of the well was sent to gaol for twelve months for obtaining money under false pretences, by pretending to put some into the well, and to fetch some out whom others had put in.

The last “priest” of the well was John Evans, who died in 1858. Doctor Bennion, of Oswestry, once said to him, “Publish it abroad that you can raise the devil, and the country will believe you.” Evans took the advice offered in jest, and confessed afterwards, “The people in a very short time spoke much about me; their conduct when they thought I held converse with the devil fairly frightened me.”

In Ireland there are several cursing wells. There boulders are placed on the low wall that surrounds the well, and he who wishes to call down a curse upon another turns the stone against the sun thrice whilst repeating the curse and the name of the person on whom he desires it to fall.

Penmaenmawr, to the west of Conway, is a favourite watering-place, and takes its name from the hill, 1,180 feet high, that rises steeply from the sea and commands a tract like Cantref y Gwaelod, that was about the same time overflowed by the sea. The story told of this sunken land is that King Helig was feasting with his lords and ladies where now lies the sandbank bearing his name, when the cellarer, having gone down to broach another cask, rushed up the steps in terror at finding the cellar under water, and he shouted, “The sea! the sea is on us!” The panic-stricken revellers fled for their lives, and as they issued from the palace heard the roar of the waves and could see the gleam of the manes of the white horses as they overleaped the sea wall.

Half a mile from Penmaenmawr is Trwyn-y-wylfa, the Headland of Wailing, for there the survivors congregated and looked over a tumbling sea that covered what had once been fair pastures and quiet homesteads. Tyno Helig, the lost land of Helig, stretched between Puffin Island and Penmaenmawr; and the Lavan sandbank covers a portion of it. The story reappears in many places with variations. In Brittany the same is told of King Grallo. He was warned to fly from his palace by S. Winwaloe, as the vengeance of Heaven would fall on it on account of the disorderly life of his daughter Ahes, and there the sea encroached and overwhelmed the palace and town.

But the most curious instance of the reduplication of the story is found in the marshes of Dol, in Brittany, where is a little lake which, in popular belief, covers a great city, and it is called la Crevée de Saint Guinou. Here we have actually the name of Gwyddno transferred to Lesser Britain. The colonists must have carried the story with them to their new home, and located it there. The morass was not formed till an inundation that took place in 709. The whole of Mount’s Bay, in Cornwall, was also at one time land, and William of Worcester, in his Itinerary, wrote: “All this region was once covered with dense forest, and extended six miles from the sea, a suitable place for wild beasts, and in which at one time lived monks serving God.”

The existence of submarine forests along this north coast of Wales and in Cardigan Bay, as well as off the south coast of Cornwall, may have originated the legend of the sunken land. In 1893, for instance, after a gale, a submerged forest was disclosed at Rhyl, nearly a mile east of the pier. But it is also quite possible that the tradition preserves the memory of a real subsidence.

In Brittany the sinking of the land is still going on. In an island of the Morbihan are two circles of standing stones. One is already half under water, and the other is completely submerged. At Locmariaquer a Roman camp is almost wholly engulfed, and Roman constructions of a villa that were observed and described in 1727 are now permanently under water.

But the submerged forests belong to a much earlier period than the sixth century, though to a time when man lived on the land and hunted in these forests. Gerald of Windsor, in the twelfth century, was puzzled at the revelation of trees beneath the waters of S. Bride’s Bay. He says: —

“The sandy shores of South Wales being laid bare by the extraordinary violence of a storm, the surface of the earth which had been covered for many ages reappeared, and discovered the trunks of trees cut off, standing in the sea itself, the strokes of the hatchet appearing as if only made yesterday; the soil was very black and the wood like ebony.”

Among the bones found in these underwater forests are those of the brown bear and the stag; the trees were Scotch firs, oaks, yews, willows, and birches, and they show by the way they have fallen, with their heads pointing to the east, that the prevailing wind, then as now, was from the west. The size of the trees proves that they must have grown at some considerable distance from the sea-board. Indeed, the forest land can be pretty well made out. The whole of Cardigan Bay was above the sea, and the promontory of Lleyn and Bardsey were heights rising out of the woodland. The stretch of forest extended a long way to the north of Wales, and the coasts of Lancashire and Cheshire were many miles further out to sea than they are now. The men who chased in this primeval forest used flint weapons; the age of metal had not then dawned.

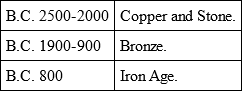

According to Montelius of Stockholm an absolute chronology can now be given for periods of prehistoric civilisation in Europe, because Copper, Bronze, and Iron Ages are contemporaneous with an historic period in Egypt and Western Asia, and also because numerous points of connection are known between the different parts of Europe and the East from the beginning of the Copper Age onwards.

He fixes the periods as follows: —

Now the Stone Age preceded that of Copper. So we must throw back the period of this vast forest to something like three thousand years before the Christian era.

Those who are satiated with the study of the tripper and the holiday-takers, and can wrench themselves from the contemplation of their sportive gambols, will take the train to Tal-y-cafn and walk thence to Caerhun, that occupies the site of the Roman town Conovium. This town did not give its name to the Conway, but took its title from it.

The Dulyn is a tributary of the Conway at Tal-y-bont (the Head of the Bridge), and it flows from the little lakes Llyn Dulyn (the Black Pool) and Melynllyn (the Yellow Pool), the former under fine crags, and forms a beautiful fall on its way.

Another stream, Afon Porthlwyd, issues from a much larger lake, the Llyn Eigiau, lying 1,220 feet above the sea under precipices of rock; and another again, the Afon Ddu, or Black River, rises in a still larger lake, the Llyn Cowlyd.

At Pen-y-Gaer, above Afon Dulyn and the little church of Llanbedr-y-Cennin, is a prehistoric camp of stone, with obstacles set in the soil, stones planted on end on the glacis, so as to break up an onrush of the enemy, in a manner seen in the Aran Isles off Ireland, some castles in Scotland, and one in Brittany. Where upright stones were not erected, sometimes the slope before the walls was purposely strewn with rubble or slates, and the assailants had to stumble over these slowly and with difficulty, exposed to volleys of arrows or stones, before they could come to close quarters. In some of the camps are great cairns of stones of a handy size piled up to serve as a store of missiles for the besieged.

It has often been remarked that these camps are away from springs and watercourses; and one wonders how those who held them managed for drink. But almost certainly they never were intended to stand long sieges. They were places of refuge. When an enemy appeared or was signalled by beacons, the inhabitants of the valleys and plains fled to them, driving their cattle before them and carrying their poor possessions on their backs. The foe came on and endeavoured to storm the stronghold; if he failed to do this at once, he abandoned the attempt, and did not sit down before it to reduce it by starvation. In some camps there are underground storehouses rudely constructed of stones set on end and roofed over, where the treasures of the tribe were concealed.

There is a story in the Norse Saga of Örvar Odd, of how he and other northern Vikings came on just such a subterranean passage. A great flat stone lay over it, but he chanced to pull it up, and found the entrance. He went in, and found it full of women in hiding. One was so pretty that he took hold of her and tried to drag her out, but the other women, screaming, held her back.

“You shall come with me,” said Odd.

“Let me buy my freedom,” she pleaded. “I have gold and silver to pay for it.”

“I have plenty of that,” answered the Northman.

“Then I have gay clothing I will give,” she said.

“And of that I have abundance,” he replied.

“Then,” said she, “I promise to embroider for you a beautiful kirtle with gold thread in it, and so thick with the precious wire that no sword will cut through it.”

“That is something,” he said. “But when may I have it?”

“Come next year, and the kirtle shall be done,” she answered. And he agreed, and allowed the women to remain without further molestation.

In the River Conway at Gored Wyddno was the salmon weir of Gwyddno, who had lost his land through the inundation of the sea in Cardigan Bay. He had a son called Elphin, who had so wasted his substance that he was obliged to fall back on his father for help, and Gwyddno consented to allow him for a while the profit of his salmon weir. Coming one morning to it he found there a babe in a leather bag, apparently a leather-covered coracle that had drifted down-stream. “What a bright-browed little chap!” exclaimed Elphin, so Taliessin, or Bright-brow, became his name, and he grew up to be a famous bard. At Christmas, long after this, Elphin was at the court of Maelgwn at Deganwy, and the bards then vied with one another in flattering the king and his queen. He was the handsomest, the wisest, the mightiest of monarchs, and she was the loveliest and most virtuous woman in the world. Elphin had the indiscretion to demur to this, and say that his wife was the chastest on earth. The story runs something like that of Posthumus and Imogen, but there are differences. Maelgwn, highly incensed, ordered Elphin to be cast into prison, and sent his son Rhun to test the lady. But Elphin had time to forewarn her, and she dressed her maid in her clothes, and put his ring on her finger. Rhun was completely deceived; he returned to Deganwy, and cast a finger with a ring on it upon the table, and declared that he had cut it off from the false wife’s hand. Elphin was brought from prison, and was shown the finger. “It is not that of my wife,” said he, “for the finger is larger than hers, and the ring has not been put on it further than the middle joint. The nail has not been cut for a month, whereas my lady trims her nails every Saturday. She from whom this finger has been cut has been recently baking rye bread – you may see the dough under the nail. That is what my wife never does.” So the laugh was turned against Rhun.

CHAPTER IX

S. ASAPH

Situation of the city – The cathedral – Tomb of Bishop Barrow – Epitaph of Dean Lloyd – The Red Book of S. Asaph– Dick of Aberdaron – Parish church – Catherine of Berain – Meiriadog – The legend of Cynan, and of the Eleven Thousand Virgins – Ffynnon Fair – Cefn caves – Plas Newydd – Cawr Rhufoniog – Covered avenue – Rhuddlan – The air “Morfa Rhuddlan” – Welsh airs – Need for careful examination and discrimination – Stories connected with certain tunes – Welsh hymn tunes – Gruffydd ab Llewelyn – Constitution of Rhuddlan – Edward “Prince of Wales.”THE city of S. Asaph is pleasantly planted, for the most part, on rising ground above the River Elwy, in the vale of the Clwyd, which unites with the Elwy below this miniature city.

The cathedral is small and not particularly interesting, and the interior effect is spoiled by the choir being moved under the central tower, and the transepts being closed in to form vestries, chapter house, consistory court, and library. The structural choir is a mere chancel without aisles, and possibly the dean, canons, and choristers may have felt cramped in it; but the alteration has robbed the interior effect of its dignity. The clerestory windows are square-headed, and the arches of the nave rise from pillars without capitals. The chancel was restored by Sir Gilbert Scott in the Early English style, and contains some good modern glass, and some that is execrable.

Outside the cathedral, at the west end, is the tomb of Bishop Isaac Barrow, who died in 1680, with the epitaph: “O vos transeuntes in Domum Domini, domum orationis, orate pro conservo vestro ut inveniam misericordiam in Die Domini.”

In the cathedral yard is a cross, with eight figures about it, of those who assisted in the translation of the Bible into Welsh, but it commemorates especially the tercentenary of Bishop Morgan’s first complete translation, published in 1588.

One of the deans of S. Asaph, Dr. David Lloyd, who died in 1663, is said to have made for himself the following epitaph: —

“This is the epitaphOf the Dean of S. Asaph,Who, by keeping a tableBetter than he was able,Ran much into debtWhich is not paid yet.”He was buried at Ruthin, of which he was once warden, but there is no monument there to his memory.

In the episcopal library is preserved the Red Book of S. Asaph, originally compiled in the fourteenth century, containing a fragmentary life of the saint who gives his name to the church and diocese, and early charters and other documents connected with it.

The site was granted to S. Kentigern, of Glasgow, when driven away by the king of Strathclyde, Morcant, and he only returned after the defeat, in 573, of Morcant by Rhydderch Hael. Then he left his favourite disciple Asaph to take charge of the foundation he had made on the banks of the Elwy.

In the cathedral library is preserved the polyglot dictionary of Dick of Aberdaron, a literary vagabond. He is reported to have acquired thirty-four languages. He was a dirty, unkempt creature, who wandered about the country, his pockets stuffed with books. His predominant passion was the acquisition of languages. A dictionary or a grammar was to him a more acceptable present than a meal or a suit of clothes. He had no home, and was sometimes obliged to sleep in outhouses.

Bishop Carey did what he was able for him, but his personal habits made him unsuitable to have in a decent house, and he was impatient of every restraint. He died in 1843, and was buried at S. Asaph.

The little parish church consists of nave and aisle of equal length – one dedicated to S. Kentigern and the other to S. Asaph. It lies at the bottom of the hill, and has a somewhat original Perpendicular east window.

Not far from S. Asaph is Berain, the residence once of Catherine Tudor, an heiress with royal blood in her veins, for she was descended from Henry VII., who, when he was in Brittany collecting auxiliaries for his descent on England to win the crown from Richard III., had an intrigue with a Breton lady named Velville, and became the father of Sir Roland Velville. Sir Roland’s daughter and heiress, Jane, married Tudor ab Robert Vychan of Berain, and their only child was Catherine. She is commonly spoken of as Mam Cymru, the Mother of Wales, as from her so many of the Welsh families derive descent.

She was first married to John Salusbury of Lleweni, and by him became the mother of Sir John Salusbury, who was born with two thumbs on each hand, and was noted for his prodigious strength. At the funeral of her husband, Sir Richard Clough gave her his arm. Outside the churchyard stood Maurice Wynn of Gwydir, awaiting a decent opportunity for proposing to her. As she issued from the gate he did this. “Very sorry,” replied Catherine, “but I have just accepted Sir Richard Clough. Should I survive him I will remember you.”

She did outlive Clough and married Wynn. She further survived Wynn, and her fourth husband was Edward Thelwall of Plas-y-Ward. She died August 27th, and was buried at Llannefydd, September 1st, 1591, but without a monument of any kind.

Popular tradition will have it that she had six husbands in succession, and that as she tired of them she poured molten lead into their ears when they slept, and so killed them. Her last husband, seeing that her affection towards him was cooling, and fearing lest he should meet with the same fate as her former husbands, shut her up in a room that is still shown at Berain, and starved her to death. There are several supposed portraits of Catherine to be found in Wales, but not all are genuine. One by Lucas de Heere, painted in 1568, is in the possession of Mr. R. J. Ll. Price of Rhiwlas, near Bala, and shows her to have been a very beautiful woman with hard, dark eyes. Another genuine portrait is at Wygfair, in the possession of Colonel Howard, and this was taken when Catherine was an old woman. The remorseless stony eye is that of one quite capable of the trick of the molten lead.

In a lovely situation on the Elwy is Meiriadog, whence came Cynan, brother or cousin of the road-building Elen. When Maximus went to Gaul to assert his claims to the purple, Cynan accompanied him and never returned. Much fabulous matter has attached itself to this Cynan. It was supposed that after the death of Maximus he retired to Brittany, with all the gallant youths who had accompanied him to the war, and as they were forbidden to return home they appealed for a shipload of wives to be sent out to them. Accordingly Ursula, daughter of Dunawd, a Welsh king, started with eleven thousand marriageable damsels, but they were carried by adverse winds up the Rhine, and landing at Cologne were there massacred by the Huns. The walls of a church there are covered with little boxes containing their skulls.

The earliest mention of these gay young wenches starting out husband-hunting, and meeting instead with a gory death, is found in a sermon preached between 752 and 839, but in it Ursula is not named. In an addition to the chronicle of Sigebert of Gemblours, made by a later hand, is an entry under 453: —

“The most famous of wars was that waged by the white-robed army of 11,000 Holy Virgins under their leader, the holy Ursula. She was the only daughter of Nothus (Dunawd), a most noble and rich prince of the Britons.”

She was sought in marriage, the writer goes on to say, by “a certain most ferocious tyrant,” and her father wished her to marry him. But Ursula had dedicated herself to celibacy, and the father was thrown into great perplexity. Then she proposed to take with her ten virgins of piety and beauty, and that to each, with herself, should be given an escort of a thousand other girls, and that they might be suffered to cruise about for three years and see the world. To this her father consented. And the requisite number of damsels having been raked together, Ursula sailed away with them in eleven elegantly furnished galleys. For three years they went merrily cruising over the high seas, but at the end of that time, having ventured up the Rhine to Cologne, they were all put to the sword.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, who died in 1154, gives another form to the story. He relates that the Emperor Maximian (Maximus), having depopulated Northern Gaul, sent to Britain for colonists wherewith to repeople its waste places. Thus out of Armorica he made a second Britain, which he put under the rule of Conan Meriadoc, who sent to have a consignment of British girls forwarded to him. At this time there reigned in Cornwall a king, Dinothus by name, and he listened to the appeal and despatched his daughter Ursula with eleven thousand young ladies, and sixty thousand others of lower rank. Unfavourable winds drove the fleet to barbarous shores, where all were butchered.

The story is, of course, devoid of a shred of historic truth, and is a mere romance, and a silly and poor one.

But there is something to be added.

Conan Meriadoc has figured largely in fabulous Breton history. At the beginning of the eighteenth century a priest of Lamballe, named Gallet, wrote a history for the glorification of the dukes of Rohan, and he spun a wonderful tale that imposed on later serious historians. According to him, Conan or Cynan Meiriadog, disappointed at not getting Ursula, married Darerca, the sister of S. Patrick, and from this union descended the kings of Brittany and the dukes of Rohan. This he achieved by identifying Cynan with Caw, the father of Gildas, entirely regardless of chronology, for Gildas, son of Caw, king in Strathclyde, died in 570, and Cynan was contemporary with Maximus, who was killed in 388, and Patrick was born about 410.

Dom Morice, whose History of Brittany was published in 1750, reproduces this absurd and impossible pedigree, and further identifies Conan with Cataw, son of Geraint, and uncle of S. Cybi, who died about 554.

There is a holy well, Ffynnon Fair, in the parish of Cefn, in a beautiful situation, once very famous, but the chapel is in ruins, though the spring flows merrily still. It was the “Gretna Green” of the district, for here clandestine marriages were wont to take place, celebrated by one of the vicars choral of the cathedral, till all such marriages were put a stop to by the Act of Lord Hardwicke in 1753. The chapel was of the fifteenth century, and is now overgrown with ivy, and in a clump of trees. Mrs. Hemans made this, “Our Lady’s Well,” the subject of one of her poems. In the unpretending-looking house just across the Elwy was written one of the earliest printed Welsh grammars (1593).

The Cefn caves are in an escarpment of mountain limestone high above the river, and have been carefully explored. They yielded bones of extinct animals – the cave bear, wolf, elephas antiquus, bos longifrons, reindeer, the hyæna, and the rhinoceros – but very scanty traces of man. The bones are preserved at Plas-yn-Cefn, the residence of Mrs. Williams-Wynn, on whose property the caves are. The caves are worth visiting more for the view from the rocks than for any intrinsic interest in themselves.

A quaint Elizabethan mansion, Plas Newydd, has in its wainscoted hall an inscription to show that it was built by one Foulk ab Robert in 1583 when he was aged forty-three. It is said to have been the first house in the neighbourhood covered with slates. A giant, Cawr Rhufoniog, used to visit there, and a crook is shown high up near the cornice, on which he was wont to suspend his hat. Giants, it would appear, were in days of yore pretty plentiful in this neighbourhood. The grave of one is pointed out close by, and another, Edward Shôn Dafydd, otherwise called Cawr y Ddôl, lived at an adjoining farm. His walking-stick was the axle-tree of a cart, with a huge crowbar driven into one end and bent for a handle. He and Sir John Salusbury (of the double thumbs) once fell to testing their strength by uprooting forest trees.

Between Plas Newydd and Plas-yn-Cefn, in a field, is a “covered avenue,” only it has lost all its coverers. It was in a mound called Carnedd Tyddyn Bleiddyn, with some trees on the top. When these were blown down in a storm, a little over thirty years ago, the cromlech within was exposed. It was found to contain several skeletons, in a crouching position, of what have been called the Platycnemic Men of Denbighshire.

Between S. Asaph and Rhyl is Rhuddlan with its castle in ruins. Formerly the tide washed its walls. The marsh, Morfa Rhuddlan, was the scene of a great battle, fought against the Saxons in 796, in which the Welsh, under their King Caradog, were defeated with great slaughter, and the prisoners taken were all put to the sword. The beautiful melody “Morfa Rhuddlan” has been supposed to pertain to a lament composed on that occasion; but the character of the melody is not earlier than the seventeenth century, and it apparently owes its name to the verses adapted to it by Iean Glan Geirionydd, who lived a thousand years after the event of this battle.

Welsh melodies require to be taken in hand by some musical antiquary and thoroughly investigated and sifted. It will be found that along with many noble airs that are genuinely Welsh, a goodly number are importations from England. This was inevitable, so mixed up were the Welsh with English families in the great houses and castles. Edward Jones published his Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards in 1784. He collected the tunes from harpers and singers, but he knew nothing of old English music, and was incapable of discriminating what was of home production from what was an importation; consequently, in his collection, a goodly percentage consist of English melodies.