полная версия

полная версияThe Cook and Housekeeper's Complete and Universal Dictionary; Including a System of Modern Cookery, in all Its Various Branches, Adapted to the Use of Private Families

CALF'S HEART. Chop fine some suet, parsley, sweet marjoram and a boiled egg. Add some grated bread, lemon peel, pepper, salt and mustard. Mix them together in a paste, and stuff the heart with it, after it has been well washed and cleaned. If done carefully, it is better baked than roasted. Serve it up quite hot, with gravy and melted butter.

CALF'S KIDNEY. Chop veal kidney, and some of the fat; likewise a little leek or onion, pepper, and salt. Roll the kidney up with an egg into balls, and fry it. – A calf's heart should be stuffed and roasted as a beef's heart; or sliced and made into a pudding, the same as for a steak or kidney pudding.

CALF'S LIVER. There are several ways of making this into a good dish. One is to broil it, after it has been seasoned with pepper and salt. Then rub a bit of cold butter over, and serve it up hot and hot. – If the liver is to be roasted, first wash and wipe it, then cut a long hole in it, and stuff it with crumbs of bread, chopped anchovy, herbs, fat bacon, onion, salt, pepper, a bit of butter, and an egg. Sew up the liver, lard or wrap it in a veal caul, and put it to the fire. Serve it with good brown gravy, and currant jelly. – If the liver and lights are to be dressed together, half boil an equal quantity of each; then cut them in a middling-sized mince, add a spoonful or two of the water that boiled it, a bit of butter, flour, salt and pepper. Simmer them together ten minutes, and serve the dish up hot.

CALF'S SWEETBREADS. These should be half boiled, and then stewed in white gravy. Add cream, flour, butter, nutmeg, salt, and white pepper. Or do them in brown sauce seasoned. Or parboil, and then cover them with crumbs, herbs, and seasoning, and brown them in a Dutch oven. Serve with butter, and mushroom ketchup, or gravy.

CALVES. The general method of rearing calves consumes so much of the milk of the dairy, that it is highly necessary to adopt other means, or the calves must be sold to the butcher while they are young. A composition called linseed milk, made of linseed oil-cake powdered, and gradually mixed with skim-milk sweetened with treacle, has been tried with considerable effect. It must be made nearly as warm as new milk when taken from the cow. Hay tea mixed with linseed and boiled to a jelly, has likewise been tried with success. A species of water gruel, made in the following manner, is strongly recommended. Put a handful or two of oatmeal into some boiling water, and after it has thickened a little, leave it to cool till it is lukewarm; mix with it two or three pints of skim-milk, and give it to the calf to drink. At first it may be necessary to make the calf drink by presenting the fingers to it; but it will soon learn to drink of itself, and will grow much faster than by any other method. According to the old custom, a calf intended to be reared is allowed to suck for six or eight weeks; and if the cow give only a moderate quantity of milk, the value of it will amount to the price of the calf in half that time. By the method now recommended, only a little oatmeal or ground barley is consumed, and a small quantity of skim-milk. The calf is also more healthy and strong, and less subject to disease. Small whisps of hay should be placed round them on cleft sticks, to induce the calves to eat; and when they are weaned, they should be turned into short sweet grass; for if hay and water only are used, they are liable to swellings and the rot. The fatting of calves being an object of great importance, a greater variety of food is now provided for this purpose than formerly, and great improvements have been made in this part of rural economy. Grains, potatoes, malt dust, pollard, and turnips now constitute their common aliment. But in order to make them fine and fat, they must be kept as clean as possible, with fresh litter every day. Bleeding them twice before they are slaughtered, improves the beauty and whiteness of the flesh, but it may be doubted whether the meat is equally good and nutricious. If calves be taken with the scouring, which often happens in a few days after being cast, make a medicine of powdered chalk and wheat meal, wrought into a ball with some gin; and it will afford relief. The shoote is another distemper to which they are liable, and is attended with a violent cholic and the loathing of food. The general remedy in this case is milk, well mulled with eggs; or eggs and flour mixed with oil, melted butter, linseed or anniseed. To prevent the sickness which commonly attends calves about Michaelmas time, take newly-churned butter, without salt, and form it into a cup the size of an egg; into this cup put three or four cloves of bruised garlic, and fill it up with tar. Having put the cup down the calf's throat, pour into its nostrils half a spoonful of the spirit of turpentine, rub a little tar upon its nose, and keep it within doors for an hour. Calves ought to be housed a night before this medicine is given.

CALICO FURNITURE. When curtains or bed furniture of this description are to be taken down for the summer, shake off the loose dust, and lightly brush them with a small long-haired furniture brush. Wipe them afterwards very closely with clean flannels, and rub them with dry bread. If properly done, the curtains will look nearly as well as at first, and if the colour be not very light, they will not require washing for years. Fold them up in large parcels, and put them by carefully. While the furniture remains up, it should be preserved as much as possible from the sun and air, which injure delicate colours; and the dust may be blown off with bellows. Curtains may thus be kept clean, even to use with the linings after they have been washed or newly dipped.

CAMP VINEGAR. Slice a large head of garlic, and put it into a wide-mouthed bottle, with half an ounce of cayenne, two tea-spoonfuls of soy, two of walnut ketchup, four anchovies chopped, a pint of vinegar, and enough cochineal to give it the colour of lavender drops. Let it stand six weeks; then strain it off quite clear, and keep it in small bottles sealed up.

CAMPHOR JULEP. Dissolve a quarter of an ounce of camphor in half a pint of brandy. It may thus be kept fit for use; and a tea-spoonful taken in a wine glass of cold water will be found an agreeable dose. – Another way. To a quarter of an ounce of camphor, add a quart of boiling water, and a quart of cold. Let it stand six hours, and strain it off for use.

CAMPHOR OINTMENT. Put half an ounce of camphor into an ounce of the oil of almonds, mixed with an ounce of spermaceti. Scrape fine into it half an ounce of white wax, and melt it over some hot water.

CAMPHORATED OIL. Beat an ounce of camphor in a mortar, with two ounces of Florence oil, till the camphor is entirely dissolved. This liniment is highly useful in rheumatism, spasms, and other cases of extreme pain.

CANARIES. Those who wish to breed this species of birds, should provide them a large cage, with two boxes to build in. Early in April put a cock and hen together; and whilst they are pairing, feed them with soft meat, or a little grated bread, scalded rapeseed and an egg mixed together. At the same time a small net of fine hay, wool, cotton, and hair should be suspended in one corner of the cage, so that the birds may pull it out as they want it to build with. Tame canaries will sometimes breed three or four times in a year, and produce their young about a fortnight after they begin to sit. When hatched, they should be left to the care of the old ones, to nurse them up till they can fly and feed themselves; during which time they should be supplied with fresh victuals every day, accompanied now and then with cabbage, lettuce, and chick-weed with seeds upon it. When the young canaries can feed themselves, they should be taken from the old ones, and put into another cage. Boil a little rapeseed, bruise and mix it with as much grated bread, mace seed, and the yolk of an egg boiled hard; and supply them with a small quantity every day, that it may not become stale or sour. Besides this, give them a little scalded rapeseed, and a little rape and canary seed by itself. This diet may be continued till they have done moulting, or renewed at any time when they appear unhealthy, and afterwards they may be fed in the usual manner.

CANCER. It is asserted by a French practitioner, that this cruel disorder may be cured in three days, by the following simple application, without any surgical operation whatever. Knead a piece of dough about the size of a pullet's egg, with the same quantity of hog's lard, the older the better; and when they are thoroughly blended, so as to form a kind of salve, spread it on a piece of white leather, and apply it to the part affected. This, if it do no good, is perfectly harmless. – A plaster for an eating cancer may be made as follows. File up some old brass, and mix a spoonful of it with mutton suet. Lay the plaster on the cancer, and let it remain till the cure is effected. Several persons have derived great benefit from this application, and it has seldom been known to fail.

CANDIED ANGELICA. Cut angelica into pieces three inches long, boil it tender, peel and boil it again till it is green; dry it in a cloth, and add its weight in sugar. Sift some fine sugar over, and let them remain in a pan two days; then boil the stalks clear and green, and let them drain in a cullender. Beat another pound of sugar and strew over them, lay them on plates, and dry them well in an oven.

CANDIED FRUIT. Take the preserve out of the syrup, lay it into a new sieve, and dip it suddenly into hot water, to take off the syrup that hangs about it. Put it on a napkin before the fire to drain, and then do another layer in the sieve. Sift the fruit all over with double refined sugar previously prepared, till it is quite white. Set it on the shallow end of sieves in a lightly-warm oven, and turn it two or three times: it must not be cold till dry. Watch it carefully, and it will be beautiful.

CANDIED PEEL. Take out the pulps of lemons or oranges, soak the rinds six days in salt and water, and afterwards boil them tender in spring water. Drain them on a sieve, make a thin syrup of loaf sugar and water, and boil the peels in it till the syrup begins to candy about them. Then take out the peels, grate fine sugar over them, drain them on a sieve, and dry them before the fire.

CANDLES. Those made in cold weather are best; and if put in a cool place, they will improve by keeping; but when they begin to sweat and turn rancid, the tallow loses its strength, and the candles are spoiled. A stock for winter use should be provided in autumn, and for summer, early in the spring. The best candle-wicks are made of fine cotton; the coarser yarn consumes faster, and burns less steady. Mould candles burn the clearest, but dips afford the best light, their wicks being proportionally larger.

CAPER SAUCE. Add a table-spoonful of capers to twice the quantity of vinegar, mince one third of the capers very fine, and divide the others in half. Put them into a quarter of a pint of melted butter, or good thickened gravy, and stir them the same way as the melted butter, to prevent their oiling. The juice of half a Seville orange or lemon may be added. An excellent substitute for capers may be made of pickled green peas, nastursions, or gherkins, chopped into a similar size, and boiled with melted butter. When capers are kept for use, they should be covered with fresh scalded vinegar, tied down close to exclude the air, and to make them soft.

CAPILLAIRE. Take fourteen pounds of good moist sugar, three of coarse sugar, and six eggs beaten in well with the shells, boil them together in three quarts of water, and skim it carefully. Then add a quarter of a pint of orange-flower water, strain it off, and put it into bottles. When cold, mix a spoonful or two of this syrup in a little warm or cold water.

CARACHEE. Mix with a pint of vinegar, two table-spoonfuls of Indian soy, two of walnut pickle, two cloves of garlic, one tea-spoonful of cayenne, one of lemon pickle, and two of sauce royal.

CARMEL COVER. Dissolve eight ounces of double refined sugar in three or four spoonfuls of water, and as many drops of lemon juice. Put it into a copper skillet; when it begins to thicken, dip the handle of a spoon in it, and put that into a pint bason of water. Squeeze the sugar from the spoon into it, and so on till all the sugar is extracted. Take a bit out of the water, and if it snaps and is brittle when cold, it is done enough. But let it be only three parts cold, then pour the water from the sugar, and having a copper form oiled well, run the sugar on it, in the manner of a maze, and when cold it may be put on the dish it is intended to cover. If on trial the sugar is not brittle, pour off the water, return it into the skillet, and boil it again. It should look thick like treacle, but of a light gold colour. This makes an elegant cover for sweetmeats.

CARP. This excellent fish will live some time out of water, and may therefore get wasted: it is best to kill them as soon as caught, to prevent this. Carp should either be boiled or stewed. Scale and draw it, and save the blood. Set on water in a stewpan, with a little Chili vinegar, salt, and horse-radish. When it boils, put in the carp, and boil it gently for twenty minutes, according to the thickness of the fish. Stew the blood with half a pint of port wine, some good gravy, a sliced onion, a little whole pepper, a blade of mace, and a nutmeg grated. Thicken the sauce with butter rolled in flour, season it with pepper and salt, essence of anchovy, and mushroom ketchup. Serve up the fish with the sauce poured over it, adding a little lemon juice. Carp are also very nice plain boiled, with common fish sauce.

CARPETS. In order to keep them clean, they should not frequently be swept with a whisk brush, as it wears them fast; not more than once a week, and at other times with sprinkled tea-leaves, and a hair brush. Fine carpets should be done gently on the knees, with a soft clothes' brush. When a carpet requires more cleaning, take it up and beat it well, then lay it down and brush it on both sides with a hand-brush. Turn it the right side upwards, and scour it clean with ox-gall and soap and water, and dry it with linen cloths. Lay it on the grass, or hang it up to dry thoroughly.

CARRAWAY CAKE. Dry two pounds of good flour, add ten spoonfuls of yeast, and twelve of cream. Wash the salt out of a pound of butter, and rub it into the flour; beat up eight eggs with half the whites, and mix it with the composition already prepared. Work it into a light paste, set it before the fire to rise, incorporate a pound of carraway comfits, and an hour will bake it.

CARRIER SAUCE. Chop six shalots fine, and boil them up with a gill of gravy, a spoonful of vinegar, some pepper and salt. This is used for mutton, and served in a boat.

CARROLE OF RICE. Wash and pick some rice quite clean, boil it five minutes in water, strain and put it into a stewpan, with a bit of butter, a good slice of ham, and an onion. Stew it over a very gentle fire till tender; have ready a mould lined with very thin slices of bacon, mix the yolks of two or three eggs with the rice, and then line the bacon with it about half an inch thick. Put into it a ragout of chicken, rabbit, veal, or of any thing else. Fill up the mould, and cover it close with rice. Bake it in a quick oven an hour, turn it over, and send it to table in a good gravy, or curry sauce.

CARROTS. This root requires a good deal of boiling. When young, wipe off the skin after they are boiled; when old, scrape them first, and boil them with salt meat. Carrots and parsnips should be kept in layers of dry sand for winter use, and not be wholly cleared from the earth. They should be placed separately, with their necks upward, and be drawn out regularly as they stand, without disturbing the middle or the sides.

CARROT PUDDING. Boil a large carrot tender; then bruise it in a marble mortar, and mix with it a spoonful of biscuit powder, or three or four little sweet biscuits without seeds, four yolks and two whites of eggs, a pint of cream either raw or scalded, a little ratifia, a large spoonful of orange or rose-water, a quarter of a nutmeg, and two ounces of sugar. Bake it in a shallow dish lined with paste; turn it out, and dust a little fine sugar over it.

CARROT SOUP. Put some beef bones into a saucepan, with four quarts of the liquor in which a leg of mutton or beef has been boiled, two large onions, a turnip, pepper and salt, and boil them together for three hours. Have ready six large carrots scraped and sliced; strain the soup on them, and stew them till soft enough to pulp through a hair sieve or coarse cloth, with a wooden spoon; but pulp only the red part of the carrot, and not the yellow. The soup should be made the day before, and afterwards boiled with the pulp, to the thickness of peas-soup, with the addition of a little cayenne.

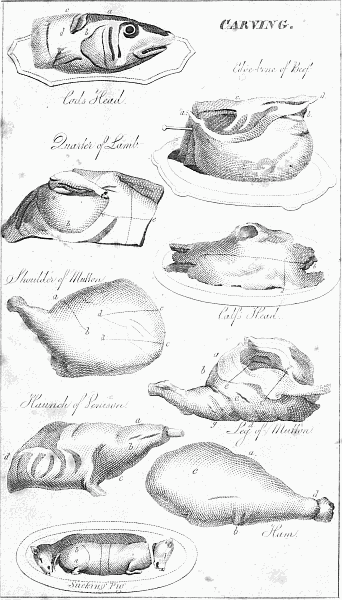

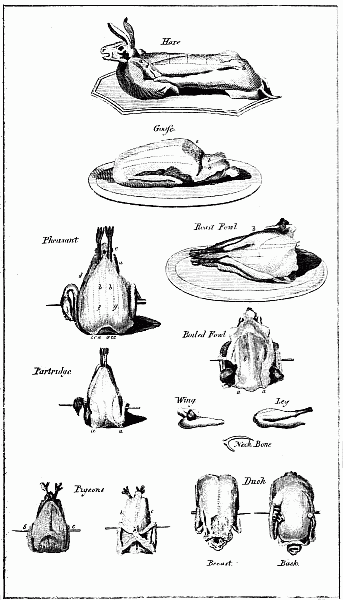

CARVING. In nothing does ceremony more frequently triumph over comfort, than in the administration of 'the honours of the table.' Every one is sufficiently aware that a dinner, to be eaten in perfection, should be taken the very moment it is sent hot to table; yet few persons seem to understand, that he is the best carver who fills the plates of the greatest numbers of guests in the least portion of time, provided it be done with ease and elegance. In a mere family circle, where all cannot and ought not to be choosers, it is far better to fill the plates and send them round, rather than ask each individual what particular part they would prefer; and if in a larger company a similar plan were introduced, it would be attended with many advantages. A dexterous carver, would help half a dozen people in less time than is often wasted in making civil faces to a single guest. He will also cut fair, and observe an equitable distribution of the dainties he is serving out. It would save much time, if poultry, especially large turkeys and geese, were sent to table ready cut up. When a lady presides, the carving knife should be light, of a middling size, and of a fine edge. Strength is less required than address, in the manner of using, it; and to facilitate this, the butcher should be ordered to divide the joints of the bones, especially of the neck, breast, and loin of mutton, lamb, and veal; which may then be easily cut into thin slices attached to the adjoining bones. If the whole of the meat belonging to each bone should be too thick, a small slice may be taken off between every two bones. The more fleshy joints, as fillet of veal, leg or saddle of mutton and beef, are to be helped in thin slices, neatly cut and smooth; observing to let the knife pass down to the bone in the mutton and beef joints. The dish should not be too far off the carver, as it gives an awkward appearance, and makes the task more difficult. In helping fish, take care not to break the flakes; which in cod and very fresh salmon are large, and contribute much to the beauty of its appearance. A fish knife, not being sharp, divides it best on this account. Help a part of the roe, milt or liver, to each person. The heads of carp, part of those of cod and salmon, sounds of cod, and fins of turbot, are likewise esteemed niceties, and are to be attended to accordingly. In cutting up any wild fowl, duck, goose, or turkey, for a large party, if you cut the slices down from pinion to pinion, without making wings, there will be more prime pieces. But that the reader may derive the full advantage of these remarks, we shall descend to particulars, and illustrate the subject with a variety of interesting Plates, which will show at the same time the manner in which game and poultry should be trussed and dished. – Cod's head. Fish in general requires very little carving, the fleshy parts being those principally esteemed. A cod's head and shoulders, when in season, and properly boiled, is a very genteel and handsome dish. When cut, it should be done with a fish trowel, and the parts about the backbone on the shoulders are the firmest and the best. Take off a piece quite down to the bone, in the direction a, b, c, d, putting in the spoon at a, c, and with each slice of fish give a piece of the sound, which lies underneath the backbone and lines it, the meat of which is thin, and a little darker coloured than the body of the fish itself. This may be got by passing a knife or spoon underneath, in the direction of d, f. About the head are many delicate parts, and a great deal of the jelly kind. The jelly part lies about the jaw, bones, and the firm parts within the head. Some are fond of the palate, and others the tongue, which likewise may be got by putting a spoon into the mouth. – Edge bone of Beef. Cut off a slice an inch thick all the length from a to b, in the figure opposite, and then help. The soft fat which resembles marrow, lies at the back of the bone, below c; the firm fat must be cut in horizontal slices at the edge of the meat d. It is proper to ask which is preferred, as tastes differ. The skewer that keeps the meat properly together when boiling is here shewn at a. This should be drawn out before it is served up; or, if it is necessary to leave the skewer in, put a silver one. – Sirloin of Beef may be begun either at the end, or by cutting into the middle. It is usual to enquire whether the outside or the inside is preferred. For the outside, the slice should be cut down to the bones; and the same with every following helping. Slice the inside likewise, and give with each piece some of the soft fat. The inside done as follows eats excellently. Have ready some shalot vinegar boiling hot: mince the meat large, and a good deal of the fat; sprinkle it with salt, and pour the shalot vinegar and the gravy on it. Help with a spoon, as quickly as possible, on hot plates. – Round or buttock of Beef is cut in the same way as fillet of veal, in the next article. It should be kept even all over. When helping the fat, observe not to hack it, but cut it smooth. A deep slice should be cut off the beef before you begin to help, as directed above for the edge-bone. – Fillet of Veal. In an ox, this part is round of beef. Ask whether the brown outside be liked, otherwise help the next slice. The bone is taken out, and the meat tied close, before dressing, which makes the fillet very solid. It should be cut thin, and very smooth. A stuffing is put into the flap, which completely covers it; you must cut deep into this, and help a thin slice, as likewise of fat. From carelessness in not covering the latter with paper, it is sometimes dried up, to the great disappointment of the carver. – Breast of Veal. One part, called the brisket, is thick and gristly; put the knife about four inches from the edge of this, and cut through it, which will separate the ribs from the brisket. – Calf's Head has a great deal of meat upon it, if properly managed. Cut slices from a to b, letting the knife go close to the bone. In the fleshy part, at the neck end c, there lies the throat sweetbread, which you should help a slice of from c to d with the other part. Many like the eye, which must be cut out with the point of a knife, and divided in two. If the jaw-bone be taken off, there will be found some fine lean. Under the head is the palate, which is reckoned a nicety; the lady of the house should be acquainted with all things that are thought so, that she may distribute them among her guests. – Shoulder of Mutton. This is a very good joint, and by many preferred to the leg; it being very full of gravy, if properly roasted, and produces many nice bits. The figure represents it as laid in the dish with its back uppermost. When it is first cut, it should be in the hollow part of it, in the direction of a, b, and the knife should be passed deep to the bone. The prime part of the fat lies on the outer edge, and is to be cut out in thin slices in the direction e. If many are at table, and the hollow part cut in the line a, b, is eaten, some very good and delicate slices may be cut out on each side the ridge of the blade-bone, in the direction c, d. The line between these two dotted lines, is that in the direction of which the edge or ridge of the blade-bone lies, and cannot be cut across. – Leg of Mutton. A leg of wether mutton, which is the best flavoured, may be known by a round lump of fat at the edge of the broadest part, as at a. The best part is in the midway, at b, between the knuckle and further end. Begin to help there, by cutting thin deep slices to c. If the outside is not fat enough, help some from the side of the broad end in slices from e to f. This part is most juicy; but many prefer the knuckle, which in fine mutton will be very tender though dry. There are very fine slices on the back of the leg: turn it up, and cut the broad end, not in the direction you did the other side, but longways. To cut out the cramp bone, take hold of the shank with your left hand, and cut down to the thigh bone at d; then pass the knife under the cramp bone in the direction, d, g. – Fore quarter of Lamb. Separate the shoulder from the scoven, which is the breast and ribs, by passing the knife under in the direction of a, b, c, d; keeping it towards you horizontally, to prevent cutting the meat too much off the bones. If grass lamb, the shoulder being large, put it into another dish. Squeeze the juice of half a Seville orange or lemon on the other part, and sprinkle a little salt and pepper. Then separate the gristly part from the ribs in the line e, c; and help either from that or from the ribs, as may be chosen. – Haunch of Venison. Cut down to the bone in the line a, b, c, to let out the gravy. Then turn the broad end of the haunch toward you, put in the knife at b, and cut as deep as you can to the end of the haunch d; then help in thin slices, observing to give some fat to each person. There is more fat, which is a favourite part, on the left side of c and d than on the other: and those who help must take care to proportion it, as likewise the gravy, according to the number of the company. – Haunch of Mutton is the leg and part of the loin, cut so as to resemble a haunch of venison, and is to be helped at table in the same manner. – Saddle of Mutton. Cut long thin slices from the tail to the end, beginning close to the back bone. If a large joint, the slice may be divided. Cut some fat from the sides. – Ham may be cut three ways. The common method is, to begin in the middle, by long slices from a to b, from the centre through the thick fat. This brings to the prime at first, which is likewise accomplished by cutting a small round hole on the top of the ham, as at c, and with a sharp knife enlarging that by cutting successive thin circles: this preserves the gravy, and keeps the meat moist. The last and most saving way is, to begin at the hock end, which many are most fond of, and proceed onwards. Ham that is used for pies, &c. should be cut from the under side, first taking off a thick slice. – Sucking Pig. The cook usually divides the body before it is sent to table, and garnishes the dish with the jaws and ears. The first thing is, to separate a shoulder from the carcase on one side, and then the leg, according to the direction given by the dotted line a, b, c. The ribs are then to be divided into about two helpings, and an ear or jaw presented with them, and plenty of sauce. The joints may either be divided into two each, or pieces may be cut from them. The ribs are reckoned the finest part, but some people prefer the neck end, between the shoulders. – Goose. Cut off the apron in the circular line a, b, c, and pour into the body a glass of port wine, and a large tea-spoonful of mustard, first mixed at the sideboard. Turn the neck end of the goose towards you, and cut the whole breast in long slices from one wing to another; but only remove them as you help each person, unless the company is so large as to require the legs likewise. This way gives more prime bits than by making wings. Take off the leg, by putting the fork into the small end of the bone, pressing it to the body; and having passed the knife at d, turn the leg back, and if a young bird, it will easily separate. To take off the wing, put your fork into the small end of the pinion, and press it close to the body; then put in the knife at d, and divide the joint, taking it down in the direction d, e. Nothing but practice will enable people to hit the joint dexterously. When the leg and wing of one side are done, go on to the other; but it is not often necessary to cut up the whole goose, unless the company be very large. There are two side bones by the wing, which may be cut off; as likewise the back and lower side bones: but the best pieces are the breast and the thighs, after being divided from the drum-sticks. – Hare. The best way of cutting it up is, to put the point of the knife under the shoulder at a, and so cut all the way down to the rump, on one side of the back-bone, in the line a, b. Do the same on the other side, so that the whole hare will be divided into three parts. Cut the back into four, which with the legs is the part most esteemed. The shoulder must be cut off in a circular line, as c, d, a. Lay the pieces neatly on the dish as you cut them; and then help the company, giving some pudding and gravy to every person. This way can only be practised when the hare is young. If old, do not divide it down, which will require a strong arm: but put the knife between the leg and back, and give it a little turn inwards at the joint; which you must endeavour to hit, and not to break by force. When both legs are taken off, there is a fine collop on each side the back; then divide the back into as many pieces as you please, and take of the shoulders, which are by many preferred, and are called the sportman's pieces. When every one is helped, cut off the head; put your knife between the upper and lower jaw, and divide them, which will enable you to lay the upper one flat on your plate; then put the point of the knife into the centre, and cut the head into two. The ears and brains may be helped then to those who like them. – Carve Rabbits as directed the latter way for hare; cutting the back into two pieces, which with the legs are the prime. – A Fowl. The legs of a boiled fowl are bent inwards, and tucked into the belly; but before it is served, the skewers are to be removed. Lay the fowl on your plate; and place the joints, as cut off, on the dish. Take the wing off in the direction of a to b, in the annexed engraving, only dividing the joint with your knife; and then with your fork lift up the pinion, and draw the wing towards the legs, and the muscles will separate in a more complete form than if cut. Slip the knife between the leg and body, and cut to the bone; then with the fork turn the leg back, and the joint will give way if the bird is not old. When the four quarters are thus removed, take off the merrythought from a, and the neck bones; these last by putting in the knife at c, and pressing it under the long broad part of the bone in the line c, b. Then lift it up, and break it off from the part that sticks to the breast. The next thing is, to divide the breast from the carcase, by cutting through the tender ribs close to the breast, quite down to the tail. Then lay the back upwards, put your knife into the bone half-way from the neck to the rump, and on raising the lower end it will separate readily. Turn the rump from you, and very neatly take off the two sidebones, and the whole will be done. As each part is taken off, it should be turned neatly on the dish, and care should be taken that what is left goes properly from table. The breast and wings are looked upon as the best parts, but the legs are most juicy in young fowls. After all, more advantage will be gained by observing those who carve well, and a little practice, than by any written directions whatever. – A Pheasant. The bird in the annexed engraving is as trussed for the spit, with its head under one of its wings. When the skewers are taken out, and the bird served, the following is the way to carve it. Fix a fork in the centre of the breast; slice it down in the line a, b; take off the leg on one side in the dotted line b, d; then cut off the wing on the same side in the line c, d. Separate the leg and wing on the other side, and then cut off the slices of breast you divided before. Be careful how you take off the wings; for if you should cut too near the neck, as at g, you will hit on the neck-bone, from which the wing must be separated. Cut off the merrythought in the line f, g, by passing the knife under it towards the neck. Cut the other parts as in a fowl. The breast, wings, and merrythought, are the most esteemed; but the leg has a higher flavour. – Partridge. The partridge is here represented as just taken from the spit; but before it is served up, the skewers must be withdrawn. It is cut up in the same manner as a fowl. The wings must be taken off in the line a, b, and the merrythought in the line c, d. The prime parts of a partridge are the wings, breast, and merrythought; but the bird being small, the two latter are not often divided. The wing is considered as the best, and the tip of it reckoned the most delicate morsel of the whole. – Pigeons. Cut them in half, either from top to bottom or across. The lower part is generally thought the best; but the fairest way is to cut from the neck to a, rather than from c to b, by a, which is the most fashionable. The figure represents the back of the pigeon; and the direction of the knife is in the line c, b, by a, if done the last way.