полная версия

полная версияFrom Crow-Scaring to Westminster: An Autobiography

During this year I received again one or two offers to go on a lecturing tour, all of which I declined. I was not, however, to remain in the shade and inactive long. The men again began to be restless and were anxious to have another try at organizing.

CHAPTER V

DARE TO BE A UNION MAN

IN the autumn of 1889 the men in Norfolk began to want to form a Union again. This time they appealed to me to lead them in the district in which I lived. For some weeks I refused to take any leading part, but was willing to join a Union. I had only just got settled down comfortably after my terrible eighteen months of bitter persecution, and was just anxious to remain quietly at work. I had no wish to enter into the turmoil of public life. But at last, through the men's constant pleadings, I yielded to the pressure. On November 5, 1889, eleven men formed a deputation and came to my house and stated they represented a large number of men in the district who had decided to form a Union and they wanted me to lead them. I questioned them in order to ascertain if they had seriously thought the matter over. They assured me they had. I also informed them that in my judgment no Union would stand which had no other object than merely to raise wages and that they must go in for something higher than that. I then asked them what Union they wished to form, or did they wish to link up with Arch's Union which was almost defunct. They expressed a wish to form a Union on the same lines as Mr. Rix had formed his, and I was asked to write to Mr. Rix to come over and address one or two meetings and explain the rules of his Union. This I did. Mr. Rix agreed to come, and two meetings were arranged to be held within a fortnight, one at the White Horse Inn at Cromer and the other at the Free Methodist Church at Aylmerton. Both meetings were packed and were addressed by George Rix and myself. Large numbers gave in their names for membership. It was decided to form a Union on the principle of the rules as explained by Mr. Rix, to be called the Federal Union, Cromer District. The objects of the Union were to be as follows: To improve the social and moral well-being of its members; to assist them to secure allotments and representation on local authorities and even in the Imperial Parliament; to assist members to migrate and emigrate. Ten shillings per week to be paid in strike and victimization pay. Legal advice to be given. Each member to pay 1s. per year harvest levy to enable a member to have his harvest money made up to him in case of a dispute. Each member to pay a contribution of 2¼d. per week, or 9d. per month, 8d. per month to be sent to the district and 1d. per month to be kept by the branch for branch management.

I was elected District Secretary, with no salary fixed for the office. I set about the work in all earnestness, addressing five meetings a week, and writing articles in the weekly papers each week. I kept at my daily work all this time, my employer, Mr. Ketton, putting nothing in my way, allowing me to leave my work an hour early whenever I required to do so and always allowing me to go "one journey." I opened branches at Gresham and Alby Hill (the very place at which I was turned out of my house only five years before). Branches were also opened at Aylsham, Hindolveston, Foulsham, Reepham, Guestwick, Kelling, Southrepps, Gunthorpe, Barney, Guist, Cawston, Bintry, and Lenwade. To many of these places I had to walk, as there was no train service except in a few instances and then only one way. Numbers of the villages were ten and twelve miles from my home. I often left a meeting at ten o'clock at night and reached home at two o'clock in the morning. I could not cycle in those days. This work continued for over nine months, and during this time I enrolled over 1,000 members at no expense to the Union.

In the autumn of 1890 a general meeting of the members was called, and this meeting decided I should become a whole-time officer and offered me £1 a week. This I at once declined on the ground that the labourers were only receiving 10s. per week, and said I should only take 15s. per week until the labourers received an increase in their wages. From this date, greatly against my wishes, I became a paid official of the Union. Although at this time there was a great revival of the Union spirit, and men were anxious to join a Union, the National Union, of which Mr. Arch was the leader, never again took any hold outside Norfolk. County Unions rose rapidly in other counties under various leaders, Warwickshire under the leadership of Mr. Ben Ryler, Wiltshire was financed by Mr. Louis Anstie of Devizes, and Berkshire was financed by the Misses Skirrett of Reading and led by Mr. T. Quelch. All these were, however, short-lived. In Norfolk we made rapid progress. Arch revived many of his branches in North-west and East Norfolk and progress was made by me in North Norfolk. I helped to start a district in South Norfolk, of which Mr. Edward James of Ditchingham became secretary. My district, not being satisfied with its isolated position, made an offer to the two other districts, namely, East Dereham and Harleston, to become amalgamated in some way, and thus enable us to become a strong force. Both, for reasons best known to themselves, preferred to remain independent. I, however, was convinced that we should never be a force strong enough to meet the farmers, who were rapidly organizing, so long as we remained little isolated Unions. In fact, we were nothing more than tiny rural Unions. I felt rather than continue along those lines I would give the whole thing up, and I placed my views before my district committee – a splendid body of men. They at once gave me full power to open correspondence with the secretary of a Norwich Union, Mr. Joseph Foyster, now a member of the Norwich bench of magistrates, and the late Mr. Edward Burgess, of "Daylight" fame, who was president of the Union, which was started about the time our Cromer district came into being. A conference of the two Unions was held at the Boar's Head, Surrey Street, Norwich, and after some discussion an agreement to amalgamate was arrived at, each district to hold its own funds and to pay a quarterly levy of 2d. per member to a central fund, which was to be used as a reserve fund in case of a dispute in either district. An Executive was elected which was to have control of the Union. Mr. Edward Burgess was elected president and Messrs. John Leeder, Robert Gotts, J. Spalding, Frank Howes, Joseph Foyster and A. Day were appointed as the Executive. A Mr. Millar of Norwich was elected General Secretary with myself as General Treasurer. I left my position as secretary to the Cromer district. This arrangement did not last long. Mr. Millar soon left the city and was never known to come back again. I was asked to accept the position of General Secretary, which I did. In the Cromer district the following were amongst my most staunch supporters: Messrs. John Leeder, James Leeder, Robert Gotts, Miles Leeder, Edward Holsey, John Spalding, Thomas Painter and Robert Leeder. These men stood by me until the last, never faltering.

The amalgamation being effected and the rules drawn up and registered, we made rapid progress. The Norwich district boundaries were fixed east and south of Norwich. I opened branches at Newton Flotman, Surlingham, Crostwick, Costessey, Eaton, Lakenham, Great Plumstead, Kirby Bedon, Rockland St. Mary, Stoke Holy Cross, Rackheath, and Salhouse. In the two districts in twelve months we reached 3,000 members. Arch's Union also made progress. The late Mr. Z. Walker was his Norfolk organizer, and that Union reached about 5,000. We never exceeded these figures. Although there was a spirit of rivalry between us, the utmost good feeling prevailed. We never went into each other's district, and always aimed at preventing overlapping, frequently appearing on each other's platforms.

Although I started out with the idea of avoiding strikes, we had not gone far before we found that was impossible. The first struggle we had was at Hindolveston. A Mr. Aberdeen set his men to cut some meadow grass and for this he offered them 3s. 6d. per acre. These terms the men rejected and a lock-out took place. I was informed and I sought an interview with the employer. This was scornfully refused and a message was sent out to me that if I went on to his place again he would set the dog on to me. I indignantly replied that I expected I was dealing with a gentleman, but regretted to find I was dealing with a man who was not sufficiently intelligent to treat another with respect. I also told him I was sure that in less than a week he would send for me and that I would then mete him out the respect he should have shown me. This was what did happen. The men would not consent to see him, but referred him to me. Within a week he sent for me and I settled the dispute by making arrangements for the men to receive 5s. per acre. That was my first effort as a leader and peace-maker. While the dispute lasted the men received the lock-out pay of 10s. per week. The next dispute was at Great Plumstead in the Norwich district and was of a more serious character for one hundred men came out in a demand for 1s. increase in wages. The greatest enthusiasm prevailed, but we found we were in for a very stiff fight. The Farmers' Federation found up a few men to fill the places of those on strike, but we were not dismayed. Enthusiastic meetings were held in every village covered by the Union, and at these songs written by members of Arch's Union were used by permission of those concerned. These were sung to well-known Sankey hymn tunes.

One favourite song sung to the tune of "Dare to be a Daniel" was: —

Standing by a purpose true,Heeding your command,Honour them, the faithful men,All hail to the Union band.Chorus.Dare to be a Union man,Dare to stand alone.Dare to have a purpose firm,Dare to make it known.Another song we sung was "The Farmer's Boy": —

The sun went down beyond the hills,Across yon dreary moor.Weary and lame, a boy there cameUp to a farmer's door."Will you tell me if any there beThat will give me employ,To plough and sow, to reap and mow,And be a farmer's boy?"Another was "The Labourer's Anthem."

The sons of Labour in the landAre rising in their might.In every town they nobly stand,And battle for the right.For long they have been trampled onBy money-making elves,But the time is come for everyoneTo rise and help themselves.Chorus.So now, you men, remember then,This is to be your plan.Nine hours a day and better pay.For every working man.This last song reveals that over forty years ago the men had the ideal of a fuller life. The struggle in question lasted nearly a month, but we gained the 1s. increase.

The next battle was fought side by side with Arch's Union. This was over the resistance of a wage reduction. It was on a large scale and was fought with great bitterness. Many of the men were evicted from their homes. This time we were not successful by reason of the fact that the years of 1891 and 1892 were years of great agricultural depression and there were large numbers of unemployed in the villages. After a bitter struggle the men went back to work at the wage offered them. This greatly dispirited the men, though I did my best to encourage them both on the platform and in the press.

CHAPTER VI

A DEFEAT AND A VICTORY

In 1892 I fought my first political battle, and for the first time my faith in the Liberal Party received a shock. In this year took place the second General County Council Election, and, by special request of the working men in the Cromer district, I allowed myself to be nominated as a Liberal-Labour candidate for that division, expecting, of course, that I should have the united support of the Liberal Party in whose interests I had worked so hard for several years. Believing them when they said they were anxious that the working man should be represented on all Authorities, one can understand my surprise and astonishment when I found the leading Liberal in the district nominating as my opponent the leading Tory in the district! I lost faith in their sincerity. It was evident they were not prepared to assist the working men to take their share in the government of the country. The contest was turned at once into a class contest. Many of the leading Liberals, as well as the Tories, expressed their disgust at a working man having the audacity to fight for a seat on the Norfolk County Council against a local landlord. My opponent was the late Mr. B. Bond Cabbell, who was returned unopposed at the first election of the Council.

The contest caused the greatest excitement. The late Mr. Henry Broadhurst, M.P., came to my help. The division comprised the towns of Cromer and Sheringham and the following villages: East and West Runton, Weybourne, Beeston Regis, East and West Beckham, Gresham, Bessingham, Sustead, Aylmerton, Metton and Felbrigg. The contest lasted three weeks, and I covered the whole district and held meetings in every village. All this I did on foot, as I could not cycle and I could not afford to hire a conveyance. The meetings were well attended, and the only help I received was from Mr. Broadhurst and from a few of my own members who were local preachers. The supporters of my opponent manifested the greatest bitterness during the contest, especially the Liberals. So far did they carry this spirit that they descended to publishing a most disgraceful cartoon, depicting a coffin with me lying in it and Broadhurst standing by the side and weeping over me. Underneath were the words: "Puzzle, find Edwards after the election." My opponent strongly condemned such action and threatened to retire unless they withdrew the thing.

The saddest thing of all was that it was my opponent who was dead within three months from the day of the election.

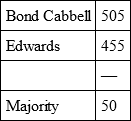

Throughout the election I was booed at by my opponent's supporters, bags of flour and soot were thrown at me, but my supporters heartened me with their cheers. The poll was a heavy one and the votes were counted at Cromer Town Hall on the night of the poll, the result being: —

There was a great crowd gathered outside the hall, my opponents being certain of victory, which they had made every preparation to celebrate. A brass band was there in readiness, and a torchlight procession was formed. I was informed the next morning that the band was worked up to such a state of excitement that the drummer broke in the end of his drum, which caused much amusement and comment not altogether to the credit of the performers.

The result, however, did not give much satisfaction to the aristocratic party; in fact, they were more bitter than ever. For a working man to run the gentlemen's party so close was more than they could tolerate, for they were afraid that at the next trial of strength Labour might win. Owing to Mr. Bond Cabbell's death another election had to take place, but I decided not to contest the seat again so soon, and my late employer, Mr. R. W. Ketton, came forward and was returned unopposed.

I then turned my attention to perfecting my organization. In the autumn of that year I opened some strong branches at Shipdham, East and West Bradenham, Saham Toney, Ashill, Earlham, Barford, Grimston, Wood Dalling, Swanton Abbott, Hockering and Weston. We were soon doomed to more trouble. Early in 1893 the men got restless. The employers seemed determined to reduce wages further. Arch's Union was seriously involved. Strikes took place at Calthorpe, Erpingham, Southrepps, Northrepps and Roughton, and our Union became involved, as we had members on the farms. Our members also came out at North Barningham, Aylmerton and Alby. A great deal of hard work and anxiety devolved upon me, as I was the only paid official in the Union. Mr. Z. Walker, the only organizer the National Union had at this time, was hardly pressed, as both Unions had members on most of the farms affected, and we frequently met and held joint meetings. I also met Mr. Arch and addressed many meetings with him and we became great friends from that time. We both saw that to have two Unions with the same objects and catering for the same class was a source of weakness, but how to find a way out of it neither of us could see.

We decided, however, so long as the movement lasted, we would work side by side without any friction.

The dispute lasted many weeks. The greatest use was made by the employers of the weapon of the tied cottage and many evictions took place.

The magistrates never hesitated when the opportunity presented to grant an eviction order.

In 1893 the Government appointed a Royal Commission to inquire into the administration of the Poor Law. Amongst those appointed to serve on the Commission were the late King (then Prince of Wales), the late Lord Aberdare, Rt. Hon. Joseph Chamberlain, M.P., Henry Broadhurst, M.P., Joseph Arch, M.P. and others. I was invited to give evidence before the Commission upon the following points: Relief in kind; its quality; the amount of allowance; the question of compelling children to support their aged parents. I obtained my facts and prepared my evidence and was called up to London to give it in March 1893. To prove the poorness of the quality of flour allowed by Boards of Guardians I obtained some of this flour and I also bought some of the best flour sold on the market. Needless to say, the contrast was enormous. The members of the Commission were astonished beyond degree at the poorness of the quality of the flour doled out by the Guardians, and I was requested by the Commission to go back and ask my wife to make some bread from the two classes of flour before completing my evidence. This I did, and the following week I took the bread with me before the Commission. The contrast in the bread was more marked even than in the flour. The late King expressed himself as shocked that such stuff was served out to the poor to eat and thanked me for the trouble I had taken in the matter.

Dealing with the inadequacy of the relief, I was requested to give cases of hardship that had come under my personal notice. I presented several cases. One came from the parish of Aylmerton, being that of a widow left with four little children, one a baby in arms. She was allowed 6d. per week each for three children and nothing for the fourth; half a stone of flour each for three and nothing for herself. In those days a widow was supposed to keep herself and one child. This poor widow's suffering was beyond degree, but this was only a sample of the suffering and extreme poverty of those who had lost the breadwinner. The case of the aged poor was even worse. I presented cases, giving the names of aged couples living together and only receiving one stone of flour and 2s. 6d. in money, and of widows (aged) receiving only half a stone of flour and 1s. 6d. in money. In fact, my own mother was only allowed 2s. 6d. per week and no flour and, further, I was called upon by the Aylsham Board of Guardians to contribute 1s. 3d. per week towards the sum allowed her by the Board, although I was only receiving 15s. per week with which to keep myself and my wife.

I also named several cases of extreme hardship of children being called upon to support their parents. I gave the cases of two agricultural labourers named Hazelwood, living at Baconsthorpe. Both were married men with large families, one, I believe, had eight children. They were both summoned before the Cromer magistrates by the Erpingham Board of Guardians to show cause why they should not contribute towards the maintenance of their aged parents.

I was cross-examined on my evidence for some hours by Mr. Joseph Chamberlain. At the close of my examination I was thanked by the late King and the other members of the Commission for my evidence. The Commission held their sittings in the Queen's Robing Room in the House of Lords. When my evidence was published it caused quite a sensation in the country, and I think the report of this Commission hastened on the passing of the District and Parish Councils Act. About this time I grew so disgusted with the treatment meted out to my mother that I absolutely refused to contribute any more towards the sum granted her by them. I told the Board they could stop the miserable 2s. 6d. per week and this they did forthwith. My wife and I at once gave notice to the landlord of the cottage in which my mother had lived for fifty years, the rent of which we had paid between us, and I decided to take her to our home and look after her. My sister had the furniture with the exception of the bed on which my mother slept and an old chest of drawers. I kept my mother until she died on February 5, 1892, without receiving a penny from anyone.

In 1894 the Government brought in a Bill known as the District and Parish Councils Bill, which provided for the establishment of a Council in every parish having a population of 300 and over, and the placing of the obtaining of allotments for the working classes in the hands of the Council, together with the appointing of trustees for Parish Charities. It also sought to abolish all property qualification in election as Guardians. Mr. Z. Walker and I jointly entered into a campaign during the passage of the Bill through Parliament, Mr. Arch paying as many visits to the county as his parliamentary duties would permit. We also had the valuable assistance of the English Land Restoration League, as it was then called, Mr. Frederick Verinder being the General Secretary. The League sent down one of their vans and a lecturer.

The Trades Union Congress was held in Norwich this year (1894). I attended the Congress as delegate from the Norfolk and Norwich Amalgamated Labour League and moved a resolution on the tied cottage system.

At the end of the session the Bill became law, and by the instructions of my Executive I set about preparing to put the Act in force. I held meetings in every village where we had branches of the Union and explained the provisions of the Act. By the time the first meetings were held to elect the Parish Councils in many of our villages we had got our men ready and well posted up in the mode of procedure as to nominations and how to carry on.

The first meeting was held in December in the village in which I lived. We held a preliminary meeting in the schools to explain the Act. This meeting was attended by the Rev. W. W. Mills, the Rector of the parish, who caused some little amusement by his constant personal interjections. For some years for some reason he had shown a personal dislike to me, and he never lost an opportunity to manifest this spirit of dislike. What influenced him I never could understand, but he always seemed jealous of my influence in the village as a Nonconformist. A few days after this meeting was held the Rector came to my house to inform me that Mrs. Mills was being nominated as a candidate for the District Council, and I informed him that I was also being nominated. He expressed a wish that the contest might be friendly. I informed him that so far as I was concerned it would. He then accused me of being the cause of the meeting referred to above being disorderly, which I stoutly denied. He then called me a liar, and it looked for a few moments as if we were in for a scuffle, for I threatened to put him out of my house and began to take steps to do so. He at once rose from his seat and rushed to the door before I could lay hands on him, but in getting away he caught my hand in the door and knocked the skin off my knuckles. My wife was in the next room, and had she not appeared on the scene I do not know what would have happened. She got between us, took the Rector by the collar and put him out of the yard. This event caused some little excitement in the village.

At the meeting held for the election of Parish Councillors all the Labour members nominated were elected. We had nominated sufficient candidates to fill all the seats but one, and this was taken by Mr. Groom, the schoolmaster. The parish of Felbrigg was also joined to Aylmerton for the purpose of forming the Parish Council, and it became known as the Aylmerton-cum-Felbrigg Parish Council. At the first meeting of the Council I was elected chairman. I was also elected on the Beckham Parish Council on which I served for some years, and I was also one of the charity trustees. One of the first things we did on the Aylmerton Council was to obtain allotments for the labourers in the parishes of Aylmerton and Felbrigg. In fact, our enthusiasm to do something was so great that it was the cause of our undoing, for at the next election we all got defeated, and I took no more interest in the affairs of the parish while I lived there.