полная версия

полная версияThe No Breakfast Plan and the Fasting-Cure

"'During her fast she was seen by seven physicians and medical professors, President MacAlister and professors of the Drexel Institute, and many others.'

"The young lady's weight at the beginning of the fast, Mr. Ritter says, was one hundred and forty pounds, and just after the meal with which she broke the fast she weighed one hundred and twenty pounds. By December 15 she had regained nine pounds, meanwhile eating one meal daily and sometimes two, with an occasional light luncheon.

"Dr. Chase, medical director of the institution above referred to, was visited on Saturday by a Ledger reporter in regard to the case of Miss K. He had been informed of her long fast and of its results, and had seen Miss K. herself when she called at the asylum on the thirty-fifth day of the fast. He said that when she was first brought to the asylum she was suffering from melancholia, and was put under the treatment which all the leading alienists had found most beneficial for persons suffering from nervous disorders, viz., quiet, rest of mind and body, and full, nourishing diet, carefully selected to produce the best results. During the time she remained at the asylum she improved both in bodily and mental health.

"Referring to the treatment she had received under Mr. Ritter's supervision since leaving the asylum, Dr. Chase said he had first heard of the system through a work published two years ago by Dr. George S. Keith, of London, from which he first learned of Dr. Dewey, who also uses the fasting cure. In all the cases cited by Dr. Keith none had been afflicted with any mental disorder. He looked upon the cases, however, as showing some remarkable results, warranting a careful study. But it would not do to adopt such a system without a most thorough examination. As 'one swallow does not make a summer,' neither will one case nor half a dozen cases cured by such a method prove anything. No universal method can be adopted for treating disease. Hardly two cases are alike. Cures also may be brought about in different ways if the exact condition of the patient is understood.

"'Mr. Ritter says the patient lent herself very willingly to the treatment, which was a great deal to start out with in her case. But I am surprised that a young man with no medical knowledge would do a thing like that. The treatment might easily have resulted differently. If he had been a doctor, he would have had that fact to sustain him in case he got into trouble. The case might very well have resulted fatally, because the treatment was so contrary to what would naturally be pursued by physicians in nervous cases.

"'I do not ridicule the system. There have been cases which were cured by ways not recognized by the general practitioner after they had been given up. I am a firm believer that in selected cases the fasting method would be efficacious, but I do not believe in its general application.

"'Mr. Ritter is evidently an enthusiast, and apt to overstate the points in favor of the method, neglecting those which tell against it. It is too early yet to say what the outcome of Miss K.'s case will be. I think the matter ought to be looked into more fully. Mr. Ritter could not have been with the patient at all times. It is a remarkable thing that she should have kept up and had the strength reported, unless she had some food. He may have been deceived in that.'"

During several months since the fast there have been the best physical health and mental condition, the weight having increased several pounds above the former average.

Mr. Ritter conducted this case in a blaze of publicity. He showed it to no less than seven physicians, some of whom were college professors, and one of them at near the close of the fast suggested that if food were not soon taken a sudden collapse would be the result. There seemed to have been less danger of this calamity on the forty-fourth day than on any other.

The reliability of the fast was so clearly evident that the leading papers of the city accepted it as authentic news and of the most startling kind. The Times gave several columns of its first page to an illustrated article.1

The accompanying illustration shows Miss Kuenzel on the forty-first day of her fast. She walked seven miles on this day without any signs of fatigue.

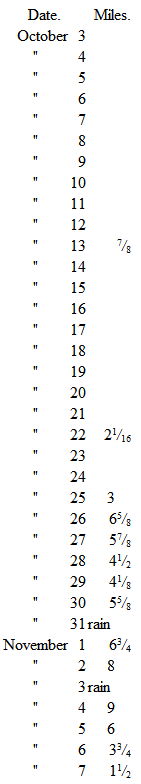

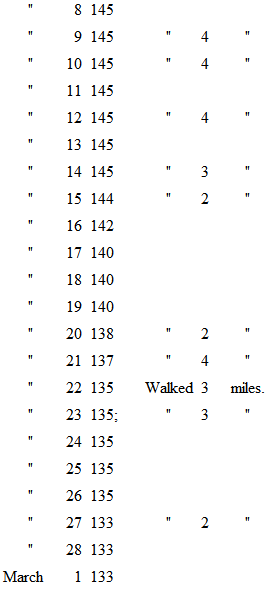

The following table of miles walked were measured from exact diary notes with bicycle and cyclometer after the fast was broken. The table gives the total sum of each day, walks being taken both afternoon and evenings of same day.

The next fast, under the care of Mr. Ritter, still holds the record as being the most remarkable for its number of days and the miracle of results. The following account of it appeared in the North American, one of whose editors had personal knowledge of its history:

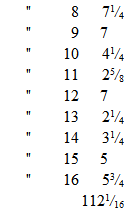

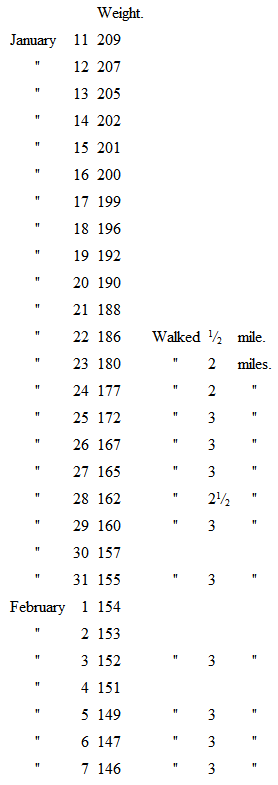

"Leonard Thress, of 2618 Frankford Avenue, has learned how to live without eating. By physical experience he has proved not only that food is not a daily necessity of the human system, but that abstinence therefrom for protracted periods is beneficial. Indeed, it saved his life. He has just finished a fifty days' fast. When he began it he was on the brink of the grave and his physicians had abandoned hope. When he ended it he was in better health than he had enjoyed for years, although in the meantime he had lost seventy-six pounds, falling away from two hundred and nine to one hundred and thirty-three pounds.

"Thress, who is about fifty-seven years old, was attending the Grand Army Encampment at Buffalo in the fall of 1898, when he caught a violent cold, which settled in his bronchial tubes. It proved so stubborn that his general health became affected, and a year later dropsy developed. His condition grew steadily worse, and at Christmas time, 1899, it was such that he could neither walk nor lie prostrate, but was compelled to sit constantly in an armchair. His doctors exhausted their skill in the effort to bring relief, and eventually, in the early part of last January, they told him that their medicines refused to act, and that his death was a question of only a few days.

"Up to this time Thress had been subsisting on the meagre diet permitted to a man in his condition, but his stomach rebelled even at that. He had heard of the Dewey fasting cure and its boasted efficacy against all human ills, and, though he had little faith, death was already looming before him, and he knew that he could lose nothing by the experiment.

"He began to fast on January 11 by taking in the morning a portion of Henzel's preparation of salts in a glass of water and the juice of two oranges, and in the evening a hot lemonade. For twenty-five days he also drank a teaspoonful of a tonic consisting chiefly of iron, but the rest of the diet he continued until two weeks ago, when he discontinued the salts and orange juice and confined himself to a hot lemonade at morning and evening. This was his only sustenance until last Thursday.

"According to Thress's own recital, the effects of this course of treatment were amazing. He says that the natural craving for food was gone after the first day. Three days later he had regained so much strength that he was able to go upstairs to bed and enjoyed a good night's sleep. From that time on, although he steadily lost in weight, his vitality grew greater, and on January 22 he left the house and took a half-mile walk.

"Before three weeks of his fast had elapsed his dropsy had disappeared, and thereafter he took almost daily walks, increasing the distance with his strength. Some days he covered as many as five miles, and never less than two, even while he was growing thinner and thinner, as the accompanying table shows.

"For the first time since the beginning of his fast he became hungry last Thursday, March 1, and he felt that he should like some pigs' feet jelly. It is one of the prescriptions of the fasting cure that when hunger finally comes the patient shall eat whatever he craves, so Thress consumed two slices of the jelly and one piece of gluten bread, with butter. He says he enjoyed it and felt well afterward.

"He ate no more that day, but at noon yesterday he became hungry again, and this time his appetite was for something more substantial. He disposed of a dish of mashed potatoes, some red cabbage, another portion of pigs' feet jelly, apple sauce, and a cream puff for dessert. He even smoked a cigar after the meal, enjoyed it, and felt still better. He says he will eat no regular meals, but only when he becomes hungry.

"While he looks haggard and worn from the loss of flesh, Thress declares that all his ailments have left him and that he never felt healthier and heartier in his life."

"The following table shows how Thress grew stronger and walked miles while he was constantly losing weight from a fifty-days' fast:

A. H. Potts, Editor of the Chester County Times, a man who has the largest faith in eating only to restore the wastes of the body, thus gives vent to his emotions after seeing the case by invitation of Mr. Ritter:

"On January 10 there sat in his home, at 2618 Frankford Avenue, Philadelphia, Mr. Leonard Thress, with dropsy, hopelessly given up to a speedy death by the many physicians he had vainly sought and paid well for relief. His weight was two hundred and nine pounds. His limbs were at the bursting point, and the water was close up to the top of his chest. He could not lie down nor even lay his head back without choking, and to walk across the room completely exhausted him. At that critical moment a friend of his heard of Miss Kuenzel's miraculous cure, and told him of it. He at once sent for Mr. Ritter, who thought that a cure was in his reach, and on January 11 Thress commenced a fast that has been absolute up to yesterday, the only things passing his lips being water, a little lemonade, and rarely the juice of an orange. Learning through the Chester County Times that we were interested in Dr. Dewey's discovery, he invited us to come and see the cases now under his care, and on Friday of last week we gladly availed ourselves of the opportunity to see the living proof of what we believed but had never seen. We were very cordially received at Mr. Ritter's home, and instead of meeting a pompous, egotistic, big man, as we might expect, we met a young gentleman of small stature, like ourselves, modest, retiring, and claiming no credit for his own part in these remarkable cures; but insisting that he is only observing the progress of cases, following in the line of truths discovered only by Dr. Dewey, giving such advice as he is enabled to do from his thorough knowledge of chemistry, anatomy, and hygiene. He took us to the house of Mr. Thress, and the startling impressions we received can never be effaced. We seemed to be in the presence of one who had arisen from the dead, and could not realize the truth of what we saw and heard from him and his estimable wife, who shows the happiness she feels in receiving her husband back to life. Impossible as it seems, yet on the previous day, as well as many other days, that man had walked three miles after six hours given to his business as a baker, which he now attends to personally. All traces of dropsy have disappeared, and his weight is now less than one hundred and thirty-five pounds, having lost this nearly seventy-five pounds of water through the natural channels at the rate of five or six pounds per day at times. His eyesight has grown younger and his hand is firm. He sleeps soundly several hours out of each twenty-four, and is almost a cured man, although the curative action is still going forward throughout his system, and his many friends are now awaiting the arrival of his normal healthy appetite, which in these cases does not arrive until the cure is entire, and then it comes in such a way as not to be mistaken. On Monday of this week we again visited him, taking a friend who has long suffered similarly to what he did, that she might see results for herself. We found him looking even better than on Friday, and it is very interesting to hear him tell his experience, which he will be glad to impart to those who are seeking after the truth, and interested in the cure of disease of themselves or their friends by this natural and without price (but priceless) means. We also visited two other of the five cases over which Mr. Ritter is at present keeping watch, and every one bore evidences of the great truth. No one should undertake the fast on their own responsibility, as certain conditions may arise requiring the eye of one who has made the matter a study, and no one should pass an opinion on the matter until they read Dr. Dewey's New Gospel of Health, wherein the reasons are made so plain that all can understand."

Mr. Thress has regained his normal weight and has been in the best of health in the several months since the fast.2

The following case was deemed a miracle by all friends: Mrs. H. B., a woman of seventy-six, became exceedingly breathless, due, it was supposed, to defective heart action that had been chronic for many years. The final result was general dropsy. The eyelids had become so heavy that reading could be indulged only a short time because of their weight; the throat was also charged with water so as to make swallowing difficult. Beneath the eyes and jaws were pockets of water – in short, the skin of the entire body was distended, a condition that had deceived the friends as revealing only an increase of her natural stoutness. The real condition became known through a call to treat a bad cold.

What had authorized medical art to promise in such a case? Absolutely nothing, as she had become too old and weak to be subjected to the ordinary means for such a general condition. As for a fast for one so old, that was the last thing that would have been thought of: her age and debility would only have seemed to invite more daily food than she had been taking.

She was put on a fast, or rather the fast was continued, the cold having abolished her appetite. It went on until the fifteenth day, with increasing general strength and diminishing weight. The last days before hunger came she was able to go up a long flight of stairs without the aid of the railing and without marked loss of breath, the heart-murmur had nearly disappeared, and water by the gallon seemed to have been absorbed.

On the fifteenth day there was a desire for food, that was taken with relish through the enlarged throat without difficulty; the water pockets had become emptied, and the lids so thin and light as to reveal no fatigue in reading. Thence on one meal a day became the rule; and since there have been five years without any recurrence of the conditions – five years of remarkable general health and girl-time relish for her daily food.

How often has the cutting down of the daily food by the old and weak been condemned as too severe an ordeal to be safe! For this woman there have been these acquired years of nearly perfect health, and the end will be in the natural, easier death of old age.

The following is inserted as additional evidence of Nature's power over disease, and that brain-workers may go on with their labors with increasing power while waiting for natural hunger in cases in which hunger is possible:

Rev. C. H. Dalrymple, of Hampden, Mass., has just completed a fast, of which he says, February 5, 1900: "My fast continued thirty-nine and one-half days. My appetite came on me about 9 o'clock at night, and I thought I would wait until the next day; but two boiled eggs and some dry toast would not retire before my presence. I have never had such an assault upon my will power as that imagined egg and toast made on me. I was finally compelled to surrender. My tongue had been clearing up that day, and the next day I was hungry at noon. I have not missed a first-class appetite at noon since. My tongue has kept clear and my taste has remained sweet. I have had no chills nor fevers this winter, nor cold in any form. I have made no allowance for my sickness and have never worked harder. My flesh came back rapidly, and now I think I must weigh about fifteen pounds more than last summer. I gained strength beyond all question about three weeks before my appetite returned. I would work all day long finally. It was good to get well."

Mr. Ritter conducted over twenty cases, some being able to carry on their usual avocations. I give the most important ones: Mr. A. H., forty-five days; Miss B. H., forty-two days; Mrs. L., thirty-eight days; Mr. L. W., thirty-six days; Miss L. J., thirty-five days; Mrs. M., thirty-one days; Miss E. S., twenty-six days; Mr. G. R., twenty-five days; Mr. P. R., twenty-four days; and Miss E. Westing, forty-two days, who, on the fortieth day, was able to sing with unusual clearness and power, and ended her fast without losing a day from her duties as a teacher of music.3

Wonderful are these fasts? Not in the physiological sense. These fasts went on with only increasing comfort by day and more refreshing sleep at night. It is quite another thing to endure the fasts of acute sickness, for such they all are. That life is maintained for days and weeks, even months, under pain, discomfort – under all the torturing conditions of such diseases as pneumonia, typhoid fever, or inflammatory rheumatism, is far more a matter to wonder over.

I may well wonder that Nature is powerful enough to cure the sick at all even under the wisest aid; but with me the abiding wonder is that physicians do not see that acute sickness is a loss of all the natural conditions of digestion, with the wasting bodies the clearest evidence that food is neither digested nor assimilated. I wonder with only increasing impatience that the stomach is not understood as a machine that Nature wills shall not be run to tax her resources when life is in the throes of disease.

XIII

I had not been long engaged in observing the evolution of cure through Nature when I began to suspect strongly, as before intimated, that fasting is the true "medicine for the mind diseased." Not less evident than the cure of various ailings would be the emergence of the soul into higher life, and in some instances from the depth of despair. As the scope of my vision constantly enlarged through multiplying experiences, I began to see great hopes of the cure of the gravest of all diseases – insanity – through a rigid application of this method in Nature. I gave the matter so much thought and study that I wrote a monograph on the subject with the idea of publishing it, but gave it up to the idea of telling my impressions in "The No-breakfast Plan."

There are the same structural changes in the evolution of insanity as in that of catarrh. There is a morbid structural basis in minds diseased, the abnormal mentality or morality being merely symptoms of a physical disease. Of all human legacies, structural weakness of the mental or moral sense is the most unfortunate.

I shall say no more about the forms of mental disease than that there is distinctively both intellectual and moral insanity as a direct result of disease of the intellectual and moral centres. This will be more clearly seen when I recall the fact that moral insanity in its worse form – the suicidal – often exists with such intellectual clearness that there is the greatest ingenuity displayed in carrying out self-destruction. These mind and soul centres are often gravely diseased without impairment of muscle energy: the furious strength of the insane is an abiding fear with all.

It is clear that weakness of structure so soft as brain, a substance which is on the dividing-line between liquids and solids, must be of the gravest form from the first: grave because so fragile, grave because the sick centres cannot rest as the broken arm, the sick body: these centres, regardless how sick, must continue to serve, even in abnormal ways.

The possibility of insanity must always be a matter of the degree of the primary structural weakness and the energy and persistence of the operative forces; on these must depend the mere gentle, persistent illusion, or that fury of mania which transforms man, the "image of the Creator," into a wild beast. That insanity, no matter what its form or degree, is an evolution from an ancestral structural legacy, not essentially different from the structural conditions evolved from those of any other chronic disease, I cannot have the slightest doubt, any more than I can have for the structural means for the cure.

There is nothing that so illustrates the civilization, the benevolence of the age and of the nations as these palaces we call hospitals for the insane. Whatever there is that can add comfort to the body, or charm to the tastes, or new life to the soul has its culmination in these palaces of wood and stone, with one great exception: the structural condition of the diseased centres indicating rest, even as the ulcer, wound, or fracture, has no part in the methods of cure.

The feeding is all done not at the time of hunger, but at the time of day. All patients are expected to eat no less than three meals a day, regardless of any desire for food and whether the patient spends all his time in bed in mindless apathy, whether pacing his room with meaningless tread, whether active in light service in the building or in heavy labor without. When there is refusal to eat it seems to be taken for granted that suicide by starvation is the design, and the pumping of food into the stomach through the nose is the common resort. There seems to be no thought that there may be no hunger in such cases, and no apprehension of any danger from not eating; that in this they follow the instincts of brutes. Would the desire for food not come and with a saner condition of mind if they were permitted their own ways of eating?

A physically strong woman, whom I knew well, was sent to a hospital for the insane in a generally bad state of mind, with destructive propensities marked. With no desire for food, and certainly with no mind to realize the need to eat without hunger, she naturally refused to eat. But for a time her meals were forced down her throat, a proceeding that taxed the strength of several strong arms.

Why were the meals not omitted long enough to cause such a reduction of strength as to make feeding less expensive in the outlay of others' muscle? The persistent refusal to eat resulted in a cessation of all efforts to enforce food; left to the gentler hands of Nature for a time, the mental hurricane subsided in great degree on the return of hunger, and long before there was an appreciable loss of weight or strength. In a few months this woman was able to return to her home, and with restored mind to tell me of the violent feedings she had endured.

Now let us look again to the structural conditions involved in diseases of the mind. There are those soft, pulpy centres from which emanate the highest powers of life: power to think, to admire, to rejoice, or to suffer; and we know how digestive power varies along the scale between ecstacy and despair. In mental disease there is the same abnormal structural change as in other local diseases; but for these sick mind-centres there is no rest. There must be still thinking and feeling, no matter how chaotic, to tax them, and there is no cheer to electrify the stomach into easy display of power. We may well marvel that powers so wonderful as the power to think, love, admire, see, hear, and feel are located in structures so fragile as the brain; and we may well marvel at the provision of the turret of flinty hardness to protect it from violence.

Now we are to consider these centres of energy as abnormally weak in all their structures at birth in those who become insane: these are the luckless legacies from the fathers and the mothers, and for how far back in the ancestral line we do not know. We are to consider that there is the same abnormal condition of the cerebral bloodvessels and of the softer inter-vascular structures as in other local diseases; and when you recall the fact that everything that worries, that adds discomfort to either mind or muscles, is a force that tends to develop weakness and disease, you will see how it applies in the evolution of insanity.