полная версия

полная версияDonald and Dorothy

For this gray wall, you must know, was but a large straight curtain of dark cotton stuff, without any fulness, stretched tightly across the doorway behind the sliding doors, and with large square or oblong pieces cut out of it here and there. Each open space thus left was bordered with a strip of gilt paper, thus forming an empty picture-frame. Don and Dorry had made the whole thing themselves the day before, and they were therefore very happy at the success of the picture-gallery, and the fun it created. They had ingeniously provided the highest pictures with small, dark curtains, fastened above the back of the frames, and hanging loosely enough to be drawn behind the living pictures, so as to form backgrounds. A draped clothes-horse answered the same purpose for the lower pictures. All of this explanation and more was given by Don and Dorry at the house-picnic to eager listeners who wished to get up exactly such a picture-gallery at their own homes some evening. But while they were talking about it somebody at the piano struck up a march – "Mendelssohn's Wedding March" – and almost before they knew it the guests found themselves marching to the music two by two in a procession across the great square hall, now lighted by a bright blaze in its open fireplace.

Donald and Dorry joined the merry line, wondering what was about to happen – when to their great surprise (ah, that sly Uncle George! and that innocent Liddy!) the double doors leading into the dining-room were flung open, and there, sparkling in the light of a hundred wax-candles, was a collation fit for Cinderella and all her royal court. I shall not attempt to describe it, for fear of forgetting to name some of the good things. Imagine what you will, and I do believe there was something just like it, or quite as good, upon that delightful table, so beautiful with its airy, fairy-like structures of candied fruits, frostings, and flowers; its jagged rock of ice where chickens and turtles, made of ice-cream, were resting on every peak and cranny; its gold-tinted jellies, and its snowy temples. Soon, fairy-work and temple yielded to ruthless boys, who crowded around with genteel eagerness to serve the girls with platefuls of delicacies, quite ignoring the rolling eye-balls of two little colored gentlemen who had been sent up from town with the feast, and who had fully expected to do the honors. Meanwhile Liddy, in black silk gown and the Swiss muslin apron which Dorry had bought for her in the city, was looking after the youngest guests, resolved that the little dears should not disgrace her motherly care by eating too much, or by taking the wrong things.

"Not that anything on that table could hurt a chicken," she said softly to Charity Cora, as she gave a bit of sponge-cake and a saucer of blanc-mange to little Isabel, "Mr. George and I looked out for that; but their dear little stomachs are so risky, you know, one can't be too careful. That's the reason we were so particular to serve out sandwiches and substantials early in the day, you know. But sakes! there's that molasses candy! I can't help worrying about it."

Charity Cora made no reply beyond a pleasant nod, for, in truth, conversation had no charms for her just then. If Donald had found you, hungry reader, modestly hidden in a corner, and with a masterly bow had handed you that well-laden plate, would you have felt like talking to Liddy?

But Liddy didn't mind. She was too happy with her own thoughts to notice trifles. Besides, Sailor Jack just at that moment came to lay a fresh log on the hall fire, and that gave her an opportunity to ask him if he ever had seen young folks "having a delighteder time."

"Never, Mistress Blum! Never!" was his emphatic, all-sufficient response.

At this very moment, Gory Danby, quite unconscious of the feast up stairs, was having his own private table in the kitchen. Having grown hungry for his usual supper of bread and milk, he had stolen in upon Norah and begged for it so charmingly, that she was unable to resist him. Imagine his surprise when, drowsily taking his last mouthful, he saw Fandy rush into the room with a plate of white grapes.

"Gory Danby!" exclaimed that disgusted brother, "I'm 'shamed of you! What you stuffin' yourse'f with common supper for when there's a party up stairs? Splendid things, all made of sugar! Pull off that bib, now, an' come along!"

Again the march struck up. Feasting was over. The boys and girls, led by Uncle George, who seemed the happiest boy of all, went back to the parlor, which, meanwhile, had been rearranged, and there, producing a great plump tissue-paper bag, he hung it to the chandelier that was suspended from the middle of the parlor ceiling. I should like to tell you about this chandelier, how it was covered with hundreds of long, three-sided glass danglers that swung, glittered, and flashed in a splendid way, now that all its wax candles were lighted: but that would interrupt the account of the paper bag. This bag was full of something, they were sure. Uncle George blindfolded Josie Manning with a handkerchief, and putting a stick in her hand, told her to turn around three times and then try to strike the bag with the stick.

"Stand back, everybody," cried Donald, as she made the last turn. "Now, hit hard, Josie! Hard enough to break it!"

Josie did hit hard. But she hit the air just where the bag didn't hang; and then the rest laughed and shouted, and begged to be blindfolded, sure that they could do it. Mr. Reed gave each a chance in turn, but each failed as absurdly as Josie. Finally, by acclamation, the bandage was put over Dorothy's dancing eyes, though she was sure she never, never could – and lo! after revolving like a lovely Chinese top, the blindfolded damsel, with a spring, and one long, vigorous stroke, tore the bag open from one side to the other. Down fell the contents upon the floor – pink mottoes, white mottoes, blue mottoes, and mottoes of gold and silver paper, all fringed and scalloped and tied with ribbons, and every one of them plump with sugar-almonds or some good kind of candy. How the guests rushed and scrambled for them! – how Fandy Danby fairly rolled over the other boys in his delight! – and how the young folks tore open the pretty papers, put the candy into their pockets, and shyly handed or sent the printed mottoes to each other! Fandy, in his excitement, handed a couplet to a pretty little girl with yellow hair, and then seeing her pout as she looked at it, ran over to her again with a quick "Let me see't. What does it say?" She held out the little bit of paper without letting it go, and Fandy seizing it at the other end, read laboriously and in laughing dismay:

"You-are-the-nicest-boy-I-know,And-this-is-just-to-tell-you-so."He recovered himself instantly, however, and wagging his handsome little head at her, exclaimed emphatically:

"Girl, girl, don't you see, I meant girl! It's pleposterous to think I meant boy, cause you ain't one, don't you see. Mottoes is awful foolish, anyway. Come over in the hall and see the gol'-fishes swimmin' in the 'quarium," – and off they ran together, as happy as birds.

Then came a dance – the Lancers. Two thirds of the young company, including Don and Dorry, attended the village dancing-school; and one and all "just doted on the Lancers," as Josie Manning said. Uncle George, knowing this, had surprised the D's by secretly engaging two players, – for piano-forte and violin, – and their well-marked time and spirited playing put added life into even the lithe young forms that flitted through the rooms. Charity looked on in rapt delight, the more so as kind Sailor Jack already had carried the sleepy and warmly bundled Isabel home to her mother.

One or two more dances brought this amusement to an end, and then, after a few moments of rest came a startling and mysterious order to prepare for the

"THANK-YOU" GAME!"What in the world is that?" asked the young folk of Don and Dorry; and their host and hostess candidly admitted that they hadn't the slightest idea what it was; they never had heard of it before.

"Well, then, how can we play it?" insisted the little spokes-people.

"I don't know," answered Dorry, looking in a puzzled way at the door.

"All join hands and form a circle!" cried a voice.

Every one arose, and soon the circle stood expectant.

"Your dear great-great fairy godmother is coming to see you," continued the voice. "She is slightly deaf, but you must not mind that."

"Oh, no, no!" cried the laughing circle, "not in the least."

"She brings her white gnome with her," said the invisible speaker; "and don't let him know your names, or he will get you into trouble."

"No, no, no!" cried the circle, wildly.

A slight stirring was heard in the hall, the doors opened, and in walked the big fairy godmother and her white gnome.

She was a tall, much bent old woman, in a ruffled cap, a peaked hat, and a long red cloak. He, the gnome, wore red trousers and red sleeves. The rest of his body was dressed in a white pillow-case with arm-holes cut in it. It was gathered at his belt; gathered also by a red ribbon tied around the throat; the corners of the pillow-case tied with narrow ribbon formed his ears, and there was a white bandage over his eyes, and a round opening for his mouth. The godmother dragged in a large sack, and the gnome bore a stick with bells at the end.

"Let me into the ring, dears," squeaked the fairy godmother.

"Let me into the ring, dears," growled the white gnome.

The circle obeyed.

"Now, my dears," squeaked the fairy godmother, "I've brought you a bagful of lovely things, but, you must know, I am under an enchantment. All I can do is to let you each take out a gift when your turn comes, but when you send me a 'Thank-you,' don't let my white gnome know who it is, for if he guesses your name you must put the gift back without opening the paper. But if he guesses the wrong name, then you may keep the gift. So now begin, one at a time. Keep the magic circle moving until my gnome knocks three times."

Around went the circle, eager with fun and expectation. Suddenly the blindfolded gnome pounded three times with his stick, and then pointed it straight in front of him, jingling the little bells. Tommy Budd was the happy youth pointed at.

"Help yourself, my dear," squeaked the fairy godmother, as she held the sack toward him. He plunged his arm into the opening and brought out a neat paper parcel.

"Hey! What did you say, dear?" she squeaked. "Take hold of the stick."

Tommy seized the end of the stick, and said, in a hoarse tone, "Thank you, ma'am."

"That's John Stevens," growled the gnome. "Put it back! put it back!"

But it wasn't John Stevens, and so Tommy kept the parcel.

The circle moved again. The gnome knocked three times, and this time the stick pointed to Dorry. She tried to be polite, and direct her neighbor's hand to it, but the godmother would not hear of that.

"Help yourself, child," she squeaked; and Dorry did. The paper parcel which she drew from the sack was so tempting and pretty, all tied with ribbon, that she really tried very hard to disguise her "Thank you," but the blindfolded gnome was too sharp for her.

"No, no!" he growled. "That's Dorothy Reed. Put it back! put it back!"

And Dorry, with a playful air of protest, dropped the pretty parcel into the bag again.

So the merry game went on; some escaped detection and saved their gifts; some were detected and lost them; but the godmother would not suffer those who had parcels to try again, and therefore, in the course of the game, those who failed at first succeeded after a while. When all had parcels, and the bag was nearly empty, what did that old fairy do but straighten up, throw off her hat, cap, false face, and cloak – and if it wasn't Uncle George himself, very red in the face, and very glad to be out of his prison. Instantly one and all discovered that they had known all along it was he.

"Ha! ha!" they laughed; "and now – " starting in pursuit – "let's see who the white gnome is!"

They caught him at the foot of the stairs, and were not very much astonished when Ed Tyler came to light.

"That is a royal game!" declared some. "Grand!" cried others. "Fine!" "First-rate!" "Glorious!" "Capital!" "As good as Christmas!" said the rest. Then they opened their parcels, and there was great rejoicing.

Uncle George, as Liddy declared, wasn't a gentleman to do things by halves, and he certainly had distinguished himself in the "Thank-you" game. Every gift was worth having. There were lovely bon-bon boxes, pretty trinkets, penknives, silver lead-pencils, paint-boxes, puzzles, thimbles, and scissors, and dozens of other nice things.

What delighted "Oh, oh's!" and merry "Ha, ha's!" rang through that big parlor. The boys who had thimbles, and the girls who had balls, had great fun displaying their prizes, and trying to "trade." After a deal of laughter and merry bargaining, the gifts became properly distributed, and then the piano and violin significantly played "Home, Sweet Home!" Soon sleigh-bells were jingling outside; Jack was stamping his feet to knock the snow off his boots. Mr. McSwiver, too, was there, driving the Manning farm-sled, filled with straw; and several turn-outs from the village were speeding chuck-a-ty-chuck, cling, clang, jingle-y-jing, along the broad carriage-way.

Ah! what a bundling-up time! What scrambling for tippets, shawls, hoods, and cloaks; what laughter and frolic; what "good-byes" and "good-byes;" what honest "thank-you's" to Mr. Reed; and what shouting and singing and hurrahing, as the noisy sleigh-loads glided away, and above all, what an "Oh, you dear, dear, dear Uncle George!" from Dorry, as she and Donald, standing by Mr. Reed's side, heard the last sleigh jingle-jingle from the door.

And then the twins went straight to bed, slept sweetly, and dreamed till morning of the house-picnic? Not so. Do you think the D's could settle down so quietly as that? True, Uncle George soon went to his room. Liddy and Jack hied their respective ways, after "ridding up," as she expressed it, and fastening the windows. Norah and Kassy trudged sleepily to bed; the musicians and colored waiters were comfortably put away for the night. But Donald and Dorothy, wide awake as two robins, were holding a whispered but animated conversation in Dorry's room.

"Wasn't it a wonderful success, Don?"

"Never saw anything like it," said Donald. "Every one was delighted; Uncle's a perfect prince. He was the life of everything too. But what is it? What did you want to show me?"

"I don't know, myself, yet," she answered. "It fell out of an old trunk that we've never looked into or even seen before; at least, I haven't. Some of the boys dragged the trunk out from away back under the farthest roof-end of the garret. It upset and opened. Robby Cutler picked up the things and tumbled them in again in a hurry; but I saw the end of a parcel and pulled it out, and ran down here to see what it was. But my room was full of girls (it was when nearly all of you boys were out in the barn, you know), and so I just threw it into that drawer. Somehow, I felt nervous about looking at it alone."

"Fetch it out," said Donald.

She did so. They opened the parcel together. It contained only two or three old copy-books.

"They're Uncle George's when he was a little boy," exclaimed Dorry, in a tone of interest, as she leaned over Donald, but with a shade of disappointment in her tone; for what is an old copy-book?

"It's not copy-writing at all," said Don, peering into the first one, "why, it's a diary!" and turning to look at the cover again, he read, "'Kate Reed.' Why, it's Aunt Kate's!"

"Aunt Kate's diary? Oh, Don, it can't be!" cried Dorry, as, pale with excitement, she attempted to take it from her brother's hands.

"No, Dorry," he said, firmly; "we must tie it up again. Diaries are private; we must speak to Uncle about it before we read a word."

"So we must, I suppose," assented Dorry, reluctantly. "But I can't sleep a wink with it in here." Her eyes filled with tears.

"Don't cry, Dot; please don't," pleaded Don, putting his arm around her. "We've been so happy all day, and finding this ought to make you all the happier. It will tell us so much about Aunt Kate, you know."

"No, Don, it will not. I feel morally sure Uncle will never let us read it."

"For shame, Dorry. Just wait, and it will be all right. You found the book, and Uncle will be delighted, and we'll all read it together."

Dorry wiped her eyes.

"I don't know about that," she said, decidedly, and much to her brother's amazement. "I found it, and I want to think for myself what is best to be done about it. Aunt Kate didn't write it for everybody to read; we'll put it back in the bureau. My, how late it must be growing," she continued, with a shiver, as, laying the parcel in, she closed the drawer so softly that the hanging brass handles hardly moved. "Now, good-night, Donald."

"What a strange girl you are," he said, kissing her bright face. "Over a thing in an instant. Well, good-night, old lady."

"Good-night, old gentleman," said Dorry, soberly, as she closed the door.

CHAPTER XVI.

A DISCOVERY IN THE GARRET

"Is Miss Dorothy in?"

"I think she is, Miss Josie. And yet, it seems as if she went over to the Danbys'. Take a seat, Miss, and I'll see if she's in her room."

"Oh, no, Kassy! I'll run up myself and surprise her."

So the housemaid went down stairs to her work, for she and Liddy were "clearin' up" after the house-picnic of the day before; and Josie Manning started in search of Dorry.

"I'll look in her cosey corner first," said Josie to herself.

Only those friends who knew the Reeds intimately had seen Dorry's cosey corner. Mere acquaintances hardly knew of its existence. Though a part of the young lady's pretty bedroom, it was so shut off by a high folding screen that it formed a complete little apartment in itself. It was decorated with various keepsakes and fancy articles – some hanging upon the walls, some standing on the mantelshelf, and some on the cabinet in which she kept her "treasures." With these, and its comfortable lounge and soft Persian rug, and, more than all, with its bright little window over-head, that looked out upon the tree-tops and the gable-roof of the summer-kitchen, it was indeed a most delightful place for the little maid. And there she studied her lessons, read books, wrote letters, and thought out, as well as she could, the plans and problems of her young life. In very cold weather, a wood fire on the open hearth made the corner doubly comfortable, and on mild days, a dark fire-board and a great vase of dried grasses and red sumac branches made it seem to Dorry the brightest place in the world.

Josie was so used to seeing her friend there that now, when she looked in and found it empty, she turned back. The cosey corner was not itself without Dorry.

"She's gone to the Danbys' after all," thought Josie, standing irresolute for a moment.

"I'll run over and find her. No, I'll wait here."

So stepping into the cosey corner again, but shrugging her pretty shoulders at its loneliness, she tossed her hood and shawl upon the sofa, and, taking up a large book of photographic views that lay there, seated herself just outside the screen, where she would be sure to see Dorry if she should enter the room. Meantime, a pleasant heat came in upon her from the warm hall, not a sound was to be heard, and she was soon lost in the enjoyment of the book, which had carried her across the seas, far into foreign scenes and places.

But Dorry was not at the Danbys' at all. She was over-head, in the garret, kneeling beside a small leather trunk, which was studded with tarnished brass nails.

How dusty it was!

"I don't believe even Liddy knew it was up here," thought Dorry, "for the boys poked it out from away, 'way back under the rafters. If she had known of it, she would have put it with the rest of the trunks."

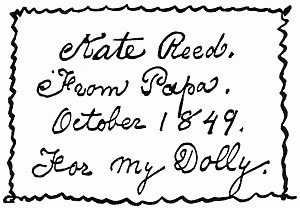

Dorry laid the dusty lid back carefully, noting, as she did so, that it was attached to the trunk by a strip of buff leather inside, extending its entire length, and that its buff-paper lining was gay with sprays of pink rose-buds. In one of the upper corners of the lid was a label bearing this inscription:

"Oh! it's Aunt Kate's own writing!" exclaimed Dorry, under her breath, as, still kneeling, she read the words.

"'From Papa,'" she repeated slowly, – "her Papa; that was Donald's and my Grandfather. And she wrote this in October, 1849 – ten whole years before we were born! and when she was only a little girl herself!"

Then, with reverent hands Dorry lifted the top article – a soft, pink muslin dress, which had a narrow frill of yellowish lace, basted at the neck. It seemed to have been cast aside as partly worn out. Beneath this lay a small black silk apron, which had silk shoulder-straps, bordered with narrow black lace, and also little pockets trimmed with lace. Dorry, gently thrusting her hand into one of these pockets, drew forth a bit of crumpled ribbon, some fragments of dried rose-leaves, and a silver thimble marked "K. R." She put it on her thimble-finger; it fitted exactly.

"Oh dear!" thought Dorry, as, with flushed cheeks and quick-beating heart, she looked at the dress and apron on her lap, "I wish Don would come!" Then followed a suspicion that perhaps she ought to call him, and Uncle George too, before proceeding further; but the desire to go on was stronger. Aunt Kate was hers, – "my aunty, even more than Don's," she thought, "because he's a boy, and of course doesn't care so much;" and then she lifted a slim, white paper parcel, nearly as long as the trunk. It was partly wrapped in an old piece of white Canton crape, embroidered with white silk stars at regular intervals. Removing this, Dorry was about to take off the white paper wrapper also, when she caught sight of some words written on it in pencil.

"Dear Aunt Kate!" thought Dorry, intensely interested; "how carefully she wrapped up and marked everything! Just my way." And she read:

My dear little Delia: I am fourteen to-day, too old for dolls, so I must put you to sleep and lay you away. But I'll keep you, my dear dolly, as long as I live, and if I ever have a dear little girl, she shall wake you and play with you and love you, and I promise to name her Delia, after you. Kate Reed. August, 1852.

With a strange conflict of feeling, and for the moment forgetting everything else, Dorry read the words over and over, through her tears; adding, softly: "Delia! That's why my little cousin was named Delia."

And, as she slowly opened the parcel, it almost seemed to her that Cousin Delia, Aunt Kate's own little girl, had come back to life and was sitting on the floor beside her, and that she and Delia always would be true and good, and would love Aunt Kate for ever and ever.

But the doll, Delia, recalled her. How pretty and fresh it was! – a sweet rosy face, with round cheeks and real hair, once neatly curled, but now pressed in flat rings against the bare dimpled shoulders. The eyes were closed, and when Dorry sought for some means of opening them, she found a wire evidently designed for that purpose. But it had become so rusty and stiff that it would not move. Somehow the closed eyes troubled her, and before she realized what she was doing, she gave the wire such a vigorous jerk that the eyes opened – bright, blue, glad eyes, that seemed to recognize her.

"Oh, you pretty thing!" exclaimed Dorry, as she kissed the smiling face and held it close to her cheek for a moment. "Delia never can play with you, dear; she was drowned, but I'll keep you as long as I live – Who's that? Oh, Don, how you startled me! I am so glad you've come."

"Why, what's the matter, Dot?" he asked, hurrying forward, as she turned toward him, with the doll still in her arms. "Not crying?"

"Oh, no, no, I'm not crying," she said, hastily wiping her eyes, and surprised to find them wet. "See here! This is Delia. Oh, Don, don't laugh. Stop, stop!"

Checking his sudden mirth, as he saw Dorry's emotion, and glancing at the open trunk, which until now had escaped his notice, he began to suspect what was the matter.

"Is it Aunt Kate's?" he asked, gravely.

"Yes, Don; Aunt Kate's doll when she was a little girl. This is the trunk that I told you about – the one that the diary fell out of."