полная версия

полная версияDonald and Dorothy

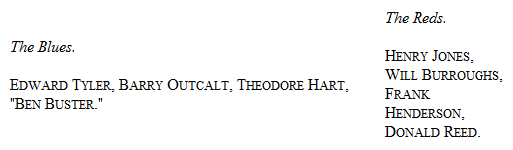

Ben Buster was missing, but a substitute was soon found, and the match began in earnest, four on a side, – the Reds and the Blues, – each wearing ribbon badges of their respective color.

Dorry had made the four red rosettes and Josie Manning the four blue ones. Besides these, Josie had contributed, as a special prize to the best marksman, a beautiful gold scarf-pin, in the form of a tiny rifle, and the winner was thenceforth to be champion shot of the club, ready to hold the prize against all comers.

Ed Tyler had carefully marked off the firing line at a distance of forty paces, or about one hundred feet from the targets; and it had been agreed that the eight boys should fire in regular order, – first a Blue, then a Red, one shot at a turn, until each had fired fifteen times in all. This was a plan of their own, "so that no fellow need wait all day for his turn." In the "toss-up" for the choice of targets and to decide the order of shooting, the Reds had won; and they had chosen to let the Blues lead off.

As Ed Tyler was a "Blue," and Don a "Red," they found themselves opponents for once. Both were considered "crack shots," but Don soon discovered that he had a more powerful rival in another of the "Blues" – one Barry Outcalt, son of the village doctor. It soon became evident that the main contest lay between these two, but Don had gained on his competitor in the sixth round by sending a fourth bullet into the bull's-eye, to Barry's second, when Ben Buster was seen strolling up the hill. Instantly his substitute, a tall, nervous fellow, nicknamed Spindle, proposed to resign in Ben's favor, and the motion was carried by acclamation, – the Blues hoping everything, and the Reds fearing nothing, from the change.

Master Buster was so resolute and yet comical, in his manner, that everyone felt there would be fun if he took part. Seeing how matters stood as to the score, he gave a knowing wink to Barry Outcalt, and said he "didn't mind pitchin' in." He had never distinguished himself at target practice, but he had done a good deal of what Dorry called "real shooting" in the West. Besides, he was renowned throughout the neighborhood as a successful rabbit-hunter.

Shuffling to his position, he stood in such a shambling, bow-legged sort of an attitude that even the politest of the girls smiled; and those who were specially anxious that the Reds should win felt more than ever confident of success.

If Don had begun to flatter himself that it was to be an easy victory, he was mistaken. He still led the rest; but for every good shot he made after that, Ben had already put a companion hole, or its better, in his own target. The girls clapped; the boys shouted with excitement. Every man of the contestants felt the thrill of the moment.

The Blues did their best; and with Outcalt and Ben on that side, Don soon found that he had heavy work to do. Moreover, just at this stage of the shooting, one of the Reds seemed to contract a sudden ambition to dot the extreme outer edge of his target. This made the Blues radiant, and would have disconcerted the Reds but for Don's nerve and pluck. He resolved that, come what might, he would keep cool; and his steadiness inspired his comrades.

"Crack!" went Don's rifle, and the bull's-eye winked in response. A perfect shot!

"Crack!" went Ed's, beginning a fresh round, and his bull's-eye didn't wink. The second ring, however, showed the bullet's track.

"Crack!" The next Red left his edge-dot on the target, as usual.

"Crack!" went Outcalt's rifle, and the rim of the bull's-eye felt it.

Will Burrough's bullet went straight to the left edge of the centre.

Hart, the third Blue, sent a shot between targets, clean into the earth-wall.

"Crack!" went the next Red. Poor Henderson! His target made no sign.

Ben Buster, the Blue, now put in his third centre shot. He was doing magnificently.

In this round, and in the next, Donald hit the centre, but it was plain that his skill alone would not avail to win the match, unless his comrades should "brace up," and better their shots; so he tried a little generalship. He urged each of the three in turn not to watch the score of the enemy at all, nor to regard the cheers of the Blues, but to give attention solely to making his own score as high as possible. This advice helped them, and soon the Reds once more were slightly ahead of the Blues, but the advantage was not sufficient to insure them a victory. As the final rounds drew near, the interest became intense. Each marksman was the object of all eyes, as he stepped up to the firing-line, and the heat of the contest caused some wild shooting; yet the misses were so evenly divided between the two companies that the score remained almost a tie.

Ed Tyler advanced to the firing-line. His shot gave the Blues' score a lift.

Now for the rim-dotter. He pressed his lips together, braced every nerve, was two whole minutes taking aim, and this time put his dot very nearly in the centre!

Outcalt was bewildered. He had been so sure Jones would hit the rim, as usual, that now he seemed bound to do it in Jones's stead. Consequently, his bullet grazed the target and hid its face in the earth-wall.

The second Red fired too hastily, and failed.

Third Blue – a bull's eye!

Third Red – an "outer."

Ben Buster stepped to the line. The Blues cheered as he raised his gun. He turned with a grand bow, and levelled his piece once more. But triumph is not always victory. His previous fine shooting had aroused his vanity, and now the girls' applause quite flustered him. He missed his aim! Worse still, not being learned in the polite art of mastering his feelings, he became vexed, and in the next round actually missed his target entirely.

Poor shooting is sometimes "catching." Now, neither Reds nor Blues distinguished themselves, until finally only one shot was left to be fired on each side; and, so close was the contest, those two shots would decide the day.

It lay between Ben Buster and Donald.

Each side felt sure that its champion would score a bull's-eye, and if both should accomplish this, the Reds would win by two counts. But if Ben should hit the bull's-eye, and Don's bullet should fall outside of even the very innermost circle, the Blues would be the victors. It was simply a question of nerve. Ben Buster, proud of his importance, marched to position, feeling sure of a bull's-eye. But, alas, for over-confidence! The shot failed to reach that paradise of bullets, but fell within the first circle, and so near the bull's-eye that it was likely to make the contest a tie, unless Donald should score a centre.

Don had now achieved the feat of gaining nine bull's-eyes out of a possible fifteen. He must make it ten, and that with a confusing chorus of voices calling to him: "Another bull's-eye, Don!" "One more!" "He can't do it!" "Fire lower!" "Fire higher!" "Don't miss!"

It was a thrilling moment, and any boy would have been excited. Don was. He felt his heart thump and his face flush, as he stepped up to the firing-line. Turning for an instant he saw Dorry looking at him proudly, and as she caught his glance, she gave her head a saucy, confident little toss as if sure that he would not miss.

"Ay! ay! Dot," said Don under his breath; and, reassured by her confidence, he calmly raised the gun to his shoulder and took careful aim.

It seemed an age to the spectators before the report broke upon the sudden hush of expectation. Then, those who were watching Don saw him bend his head forward with a quick motion, and for a second peer anxiously at the target. Then he drew back carelessly, but with a satisfaction that he could not quite conceal.

A few moments later, the excited Reds came running up, wildly waving Don's target in their arms. His last bullet had been the finest shot of the day, having struck the very centre of the bull's-eye. Even Ben cheered. The Reds had won. Donald was the acknowledged champion of the club.

But it was trying to three of the Reds, and to the Blues worse than the pangs of defeat, to see that pretty Josie Manning pin the little golden rifle on the lapel of Donald's coat.

Little he thought, amid the cheering and the merry breaking-up that followed, how soon his steadiness of hand would be taxed in earnest!

Mr. Reed, after pleasantly congratulating the winning side and complimenting the Blues upon being so hard to conquer, walked quickly homeward in earnest conversation with Sailor Jack.

CHAPTER XXI.

DANGER

The company slowly dispersed. Some of the young folk cut across lots to their homes; others, remembering errands yet to be attended to in the village, directed their course accordingly. And finally, a group of five boys, including Donald and Ed Tyler, started off, being the last to leave the shooting-range. They were going down the hill toward the house, talking excitedly about the match, and were just entering the little apple-orchard between the hill and the house, when they espied, afar off, a large dog running toward them.

The swiftness and peculiar gait of the animal attracted their attention, and, on a second look, they noted how strangely the creature hung its head as it ran.

"Hallo!" exclaimed Don, "there's something wrong there. See! He's frothing at the mouth. It's a mad dog!"

"That's so!" cried Ed. "Hurry, boys! Make for the trees!"

A glance told them plainly enough that Don was right. This was a terrible foe, indeed, for a party of boys to encounter. But the apple-trees were about them, and all the boys, good and bad climbers alike, lost not a moment in scrambling up into the branches.

All but Donald: he, too, had started for one of the nearest trees, when suddenly it occurred to him that the girls had not all left the second hill. Most of them had quitted the range in a bevy, when the match was over; but two or three had wandered off to the summer-house, under the apple-tree, where they had been discussing the affairs and plans of the Botany Club. Don knew they were there, and he remembered the old ladder that leaned against the tree; but the dog was making straight for the hill, and would be upon them before they could know their danger! Could he warn them in time? He would, at least, try. With a shout to his companions: "The girls! the girls!" he turned and ran toward the hill at his utmost speed, the dog following, and the boys in the trees gazing upon the terrible race, speechless with dread.

Donald felt that he had a good start of his pursuer, however, and he had his gun in his hand; but it was empty. Luckily, it was a repeating-rifle; and so, without abating his speed, he hastily took two cartridges from his jacket and slipped them into the chamber of the gun.

"I'll climb a tree and shoot him!" he said to himself, "if only I can warn the girls out of the way."

"Girls! Girls!" he screamed. But as he looked up, he saw, descending the hill and sauntering toward him, his sister and Josie Manning, absorbed in earnest conversation.

At first he could not utter another sound, and he feared that his knees would sink under him. But the next instant he cried out with all his might:

"Back! Back! Climb the tree, for your lives! Mad dog! Mad dog!"

The two girls needed no second warning. The sight of the dreadful object speeding up the slope in Donald's tracks was enough. They ran as they never had run before, reached the tree in time, and, with another girl whom they met and warned, clambered, breathless, up the ladder to the sheltering branches.

Then all their fears centred upon Donald, who by this time had reached the plateau just below them, where the shooting-match had been held. He turned to run toward the apple-tree, when, to the horror of all, his foot slipped, and he fell prostrate. Instantly he was up again, but he had not time to reach the tree. The dog already was over the slope, and was making toward him at a rapid, swinging gait, its tongue out, its bloodshot eyes plainly to be seen, froth about the mouth, and the jaws opening and shutting in vicious snaps.

Dorry could not stand it; she started to leave the tree, but fell back with closed eyes, while the other girls clung, trembling, to the branches, pale and horrified.

To the credit of Donald be it said, he faced the danger like a man. He felt that the slightest touch of those dripping jaws would bring death, but this was the time for action.

Hastily kneeling behind a stump, he said to himself: "Now, Donald Reed, they say you're a good shot. Prove it!" And steadying his nerves with all the resolution that was in him, he levelled his rifle at the advancing dog and fired.

To his relief, the poor brute faltered and dropped – dead, as Don thought. But it was only wounded; and, staggering to its feet again, it made another dash forward.

Don was now so encouraged, so thankful that his shot had been true, that, as he raised his gun a second time, he scarcely realized his danger, and was almost as cool as if firing at the target on the range, although the dog was now barely a dozen feet away. This was the last chance. The flash leaped from his rifle, and at the same moment Donald sprang up and ran for the tree as fast as his legs could carry him. But, before the smoke had cleared, a happy cry came from the girls in the tree. He glanced back, to see the dog lying motionless upon the ground.

Quickly reloading his gun, and never taking his finger from the trigger, he cautiously made his way back to the spot. But there was nothing to fear now. He found the poor brute quite dead, its hours of agony over.

The group that soon gathered around looked at it and at one another without saying a word. Then Dorry spoke: "Stand back, everybody! It's dangerous to go too near. I've often heard that."

A hint was sufficient. Indeed, the shuddering girls already had turned away, and the boys now drew aside, though with rather an incredulous air.

"It ought to be buried deep, just where it lies," suggested Ed; and Donald, nodding a silent assent, added, aloud: "Poor fellow! Whose dog can he be?"

"Why it's our General!" cried one of the boys. "As sure as I live it is! He was well yesterday." Then, turning pale, he added: "Oh, I must go right home – "

"Go with him, some of you fellows," Don said, gravely; "and Dot, suppose you run and let Uncle know. Ask him if we shall bury it right here."

"He will say 'yes,' of course," cried Dot, excitedly, as she started off. "I'll send Jack right back with spades."

"Yes; but tell Uncle!" Don shouted after her.

CHAPTER XXII.

A FROLIC ON THE WATER

Donald had won the gratitude of many Nestletown fathers and mothers, and had raised himself not a little in the estimation of the younger folk, by his encounter with the rabid dog. That it was a case of hydrophobia was settled by the testimony of some wagoners, who had seen the poor animal running across the road, but who, being fearful of having their horses bitten, had not attempted to stop him. Though all felt sorry for "General," everybody rejoiced that he had been put out of his misery, and that he had not bitten any one in his mad run through the fields.

As the summer advanced, and base-ball and running-matches proved to be too warm work for the season, the young folk naturally took to the water. Swimming and boating became the order of the day, and the night too; for, indeed, boats shot hither and thither through many a boy's sleep, confounding him with startling surprises and dreamland defeats and victories. But the lake sports of their waking hours were more under control. Donald and Ed Tyler, as usual, were among the most active in various contests with the oars; and as Donald believed that no event was absolutely complete if Dorry were not among either the actors or the spectators, boat-racing soon grew to be as interesting to the girls as to the boys.

The races usually were mild affairs – often impromptu, or sometimes planned in the morning and carried into effect the same afternoon. Now and then, something more ambitious was attempted: boys in rowing suits practised intently for days beforehand, while girls, looking on, formed their own not very secret opinions as to which rowers were most worthy of their support. Some went so far as to wear a tiny bit of ribbon by way of asserting allegiance to this or that crew, which sported the same color in cap, uniform, or flag. This, strange to say, did not act in the least as "a damper" on the pastime; even the fact that girls became popular as coxswains did not take the life out of it; all of which, as Dorry said, served to show the great hardihood and endurance of the boy-character.

After a while, Barry Outcalt, Benjamin Buster, and three others concocted a plot. The five held meetings in secret to complete their arrangements, and these meetings were enlivened with much smothered laughter. It was to be a "glorious joke." A boat-race, of course; and there must be a great show of previous practice, tremendous rivalry, and pressing competition, so that a strong feeling of partisanship would be aroused; while in truth, the race itself was to be a sham. The boats were to reach the goal at the same moment, nobody was to win, yet every one was to claim the victory; the air was to be rent with cries of "foul!" and spurious shouts of triumph, accompanied by vehement demands for a "fresh try." Then a second start was to be made – One, two, three, and off! All was to go well at first, and when the interest of the spectators was at its height, every eye strained and every heart almost at a standstill with excitement, two of the boats were to "foul," and the oarsman of one, in the most tragic and thrilling manner, was to fall over into the astonished lake. Then, amid the screams of the girls and scenes of wild commotion, he was to be rescued, put into his empty boat again, limp and dripping – and then, to everybody's amazement, disregarding his soaked garments and half-drowned state, he was suddenly to take to the oars in gallant style, and come in first at the close, rowing magnificently.

So ran the plot – a fine one truly. The five conspirators were delighted, and each fellow solemnly promised to stand by the rest, and not to breathe a word about it until the "sell" should be accomplished. So far, so good. Could the joke be carried out successfully? As the lake was public property, it was not easy for the two "fouling" boys to find opportunities for practising their parts. To make two boats collide at a given instant, so as to upset one and spill its occupant in a purely "accidental" way, required considerable dexterity. Ben Buster had a happy thought. Finding himself too clumsy to be the chief actor, he proposed that they should strengthen their force by asking Donald Reed to join the conspiracy. He urged that Don, being the best swimmer among the boys, was therefore best fitted to manage the fall into the water. Outcalt, on his part, further suggested that Ed Tyler was too shrewd to be a safe outsider. He might suspect, and spoil everything. Better make sure of this son of a lawyer by taking him into the plan, and appointing him sole judge and referee.

Considerable debate followed – the pros urging that Don and Ed were just the fellows wanted, and the cons insisting that neither of the two would be willing to take part. Ben, as usual, was the leading orator. He was honestly proud of Don's friendship, and as honestly scornful of any intimation that Don's better clothes and more elegant manners enhanced or hindered his claims to the high Buster esteem. Don was a good fellow, he insisted, – the right sort of a chap, – and that was all there was about it. All they had to do was to let him, Ben, fetch Don and Ed round that very day, and he'd guarantee they'd be found true blue, and no discounting.

This telling eloquence prevailed. It was voted that the two new men should be invited to join. And join they did.

Though Donald generally disliked practical joking, he yielded this time. As nobody was to be hurt, he entered heartily into the plot, impelled both by his native love of fun and by a brotherly willingness to play an innocent joke upon Dorry, who, with Josie Manning, he knew would surely be among the most interested of all the victimized spectators.

A number of neat circulars, announcing the race and the names of the six contestants, with their respective colors, were written by the boys, and after being duly signed by Ed Tyler, as referee, were industriously distributed among the girls and boys.

On the appointed afternoon, therefore, a merry crowd met at a deserted old house on the lake-shore. It had a balcony overlooking the place where the race was to begin and end.

This old building was the rendezvous of young Nestletown during boating hours; indeed, it was commonly called "the boat-house." Having been put up long years before the date of our story, it had fallen into a rather dilapidated condition when the Nestletown young folk appropriated it; but it had not suffered at their hands. On the contrary, it had been carefully cleared of its rubbish; and with its old floors swept clean, its broken windows flung open to air and sunlight, and its walls decorated with bright-colored sun-bonnets and boating flags, it presented quite a festive appearance when the company assembled in it on the day of the race.

Fortunately, its ample piazza was strong, in spite of old age and the fact that its weather-stained and paintless railing had for years been nicked, carved, and autographed by the village youngsters. It was blooming enough, on this sunny Saturday, with its freight of expectant girls and boys, many of the first-named wearing the colors of their favorites among the contestants.

The doughty six were in high spirits – every man of them having a colored 'kerchief tied about his head, and sporting bare, sinewy arms calculated to awe the beholder. Don was quite superb. So were Ben Buster and young Outcalt. Many a girl was deeply impressed by their air of gravity and anxiety, not suspecting that it was assumed for the occasion, while the younger boys looked on in longing admiration. Ed, as starter, umpire, judge, referee, and general superintendent, rowed out with dignity, and anchored a little way from shore. The six, each in his shining boat, rowed into line, taking their positions for the start. The stake-boat was moored about a third of a mile up the lake, and the course of the race was to be from the starting-line to the stake-boat, around it, and back.

The balcony fluttered and murmured as Ed Tyler shouted to the six rowers, waiting with uplifted oars:

"Are you ready? – ONE, TWO, THREE – GO!"

On the instant, every oar struck the water, the six boats crossed the line together, and the race began.

No flutter in the balcony now; the spectators were too intent.

Not for a moment could they imagine that it was not a genuine race. Every man appeared to bend to his work with a will. Soon Ben Buster, with long, sweeping strokes, went laboriously ahead; and now Outcalt and another passed him superbly, side by side. Then Don's steady, measured stroke distanced the three, and as he turned the stake-boat his victory was evident, not only to Dorothy, but to half the spectators. Not yet. A light-haired, freckled fellow in a blue 'kerchief, terribly in earnest, spun around the stake-boat and soon left Don behind; then came the quick, sharp stroke of Ben Buster nerved for victory, closely followed by Steuby Butler, who astonished everybody; and then, every man rowing as if by super-human exertion, inspired by encouraging cries from the balcony, they crowded closer and closer.

"Ben's ahead!" cried the balcony, confusedly.

"No, Donald Reed has gained on him!"

"Don't you see! it's Outcalt! Outcalt will win!"

"No, I tell you it's Butler!" – And then, before any one could see how it was done, the boats, all six of them, were at the line, oars were flourished frantically, the judge and referee was shouting himself hoarse, and the outcry and tumult on the water silenced the spectators on the land. Cries of: "Not fair!" "Not fair!" "It won't do!" "Have it again!" "Hold up!" "I won't stand such work!" culminated in riotous disorder. Seven voices protesting, shouting, and roaring together made the very waters quiver.

But Tyler was equal to the occasion. Standing in his boat, in the identical position shown in the picture of "Washington Crossing the Delaware," he managed to quiet the tumult, and ordered that the race should be rowed over again.