полная версия

полная версияThe Battle of Atlanta

During the battle, Colonel Dodge's horse was shot under him. An enlisted man, detailed as clerk in the Adjutant's office, was acting as orderly for Colonel Dodge. When his horse fell, he ordered the orderly to dismount and give him his horse. The orderly said, "You will be killed if you get on another horse; this is the third you have lost." But the orderly dismounted and stood where the Colonel had stood when he asked for the horse, and at that moment was instantly killed by a shot from the enemy. After the battle, the Adjutant, Lieutenant Williamson, found in the orderly's desk a note in which he said he was sure he would be killed in the battle, and in which, also, he left directions as to the disposal of his effects and whom to write to.

In General Price's command there was a Regiment or more of Indians commanded by Colonel Albert B. Pike. They crawled up through the thick timber and attacked my extreme left. I saw them and turned one of the guns of my battery on them, and they left. We saw no more of them, but they scalped and mutilated some of our dead. General Curtis entered a complaint to General Price, who answered that they were not of his command, and that they had scalped some of his dead, and he said he did not approve of their being upon the field. They evidently scalped many of the dead, no matter what side they belonged to.

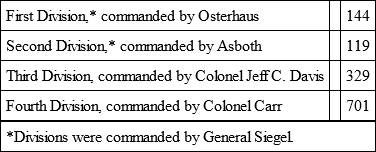

The battle of Pea Ridge being one of the first of the war and one of unquestioned victory, had a great deal of attention called to it, and for months – in fact for years, and, I think even now – was considered to have been won by General Siegel. The proper credit was not given to General Curtis, while the history and records of the battle show that he was entitled to all of the credit, and fought the battle in opposition to Siegel's views. A statement of the losses shows what commands fought the battle. The total force engaged on our side, according to General Curtis's report, was 10,500 men, formed in four Divisions, Siegel's two Divisions being the largest, the Third and Fourth Divisions having less than 2,000 men each. The losses were:

Van Dorn's and Price's reports of the battle show how great their defeat was, and why it was, and while for some time General Curtis called anxiously on Halleck for more reinforcements, demanding that the column which was marching South in Kansas be sent to him, Van Dorn and Price, from the time they left the field, never stopped until they landed at Memphis, Tenn., their first movement being towards Pocahontas, with a view of attacking Pope in the rear, who was at New Madrid. Finding New Madrid captured, they turned their forces to Desarc, and were then transported by boats to Memphis. This relieved Missouri of any Confederate force in or near its border, and General Halleck immediately gave General Curtis orders to move on the flank of Van Dorn and keep up with him, but through that swampy, hilly country it was impossible for him to meet Van Dorn, and Curtis with his Army finally landed at Helena, Ark., and most of it joined the Vicksburg siege.

Captain Phil Sheridan was the Quartermaster and Commissary of General Curtis's Army. He kept us in flour, meat, and meal, and sometimes had my whole regiment detailed in running and protecting mills, driving cattle, etc. He had great difficulty in obtaining details, as at that early day a good many commanders, and especially General Siegel and his officers, did not think it the duty of a soldier to be detailed on anything but a soldier's duty; so Sheridan naturally came to me, as he was my Quartermaster while I commanded the post at Rolla, and when with the marching column he camped and tented with me. Sheridan and Curtis had considerable difficulty, and Curtis relieved him and ordered him to report to General Halleck, at St. Louis. We who knew Sheridan's ability, and the necessities of our Army, did all we could to hold him with us. He left us just before the Battle of Pea Ridge, and our Army saw a great difference after he was gone. He used to say to me, "Dodge, if I could get into the line I believe I could do something;" and his ambition was to get as high a rank as I then had and as large a command – a Colonel commanding a Brigade. In his memoirs he pays the Fourth Iowa a great compliment, and says they will have a warm place in his heart during his life.

During the Battle of Pea Ridge Sheridan was at Springfield, Mo., preparing to turn over his property to the officer who was to relieve him, and he there showed his soldierly qualities. The dispatches from Curtis's army had to be relayed at Springfield. The first dispatches after the battle were sent all in praise of General Siegel, and by portions of his command, claiming he had won the battle. Sheridan, knowing this to be untrue, withheld the Siegel dispatches until the telegrams from General Curtis to General Halleck were received, and sent them forward first, notwithstanding the fact that he felt he had been unjustly treated by General Curtis.

This Army had no water or rail communication. It was 300 miles from its nearest supply-depot, and therefore it had to live off of a country that was sparsely settled by poor people; but Sheridan showed that dominant combination of enterprise and energy, by running every mill and using every means of supply within fifty miles of us, that he developed so fully later in the war. He kept us and our stock fairly well supplied; as I remember, there were no complaints. When General Curtis concluded to relieve him, I went with others and endeavored to induce him to change his mind. I had had experience and knew what it was to have an Army well fed a long ways from its base, and I felt that if we lost Sheridan we would suffer, which later proved to be the case; but General Curtis did not listen to us. In fact, he was angry at our appeal, and his Adjutant, General McKinney, came to see us afterwards and urged us not to press the matter; if we did, he said, we might go to the rear with Sheridan.

At the Battle of Pea Ridge and during the campaign we were very destitute of all hospital appliances for the care of the wounded, and the ability and ingenuity of our medical staff in supplying our wants was inestimable. The day after the battle, when we had all our own wounded and so many of the enemy's with us, Mrs. Governor Phelps, the wife of Governor Phelps, of Missouri, who commanded the Twenty-fifth Missouri Infantry, arrived on the field with a general supply of sanitary goods, a part of which had been sent to my Regiment from Philadelphia by the father and mother of Captain Ford, who was then a Lieutenant in Company B, Fourth Iowa Infantry. These were a great relief, as fully one-third of my command were killed and wounded, and were suffering for want of this class of goods. Mrs. Phelps spent her time day and night on the field aiding the surgeons and succoring the wounded.

General Curtis endeavored to send all the wounded to the rear who could stand the trip. I was hauled 250 miles over a rough road in an ambulance, and if any of you have had the same experience you can judge what I suffered. Captain Burton, of my Regiment, who was severely wounded in the arm, sat on the front seat of that ambulance the whole distance, and never murmured, although he came near losing his arm from the exposure. It was during this ambulance trip, while lying on my back, that I received a telegraphic dispatch from General Halleck notifying me of my promotion for services in this battle. It was thought, and was also stated in the papers, that I could not live, and I told General Halleck afterwards that they expected to have the credit of making a Brigadier-General and at the same time to have a vacancy, too, but that on the vacancy I fooled them, for the promotion insured my getting well.

This campaign demonstrated early in the war what could be accomplished by a small Army 300 miles away from any rail or water communication, in a rugged, mountainous, sparsely settled county, marching in winter, and virtually subsisting upon the country. Nothing escaped that Army that was eatable.

The Battle of Pea Ridge was fought by the two Divisions commanded by Carr and Davis, not exceeding 6,000 men, and it is a lesson in war that is very seldom appreciated: that no one can tell what the result of a battle may be, and that even where forces are very wide apart in numbers it is not always the larger force that wins. In this battle Van Dorn had put twice as many men into the fight as Curtis did, and still was defeated. His dividing his force and attacking our Army at two different points was fatal to his success, as General Curtis had the inside line and could move from one part of his command to another within an hour, while for Van Dorn to move from one portion of his Army to the other would have taken at least half a day, and therefore he was whipped in detail. If he had thrown his whole force upon Curtis's right flank at the point where McCullough fought and was overwhelmed by Davis's Division, there would have been great danger of our Army being defeated, or at least forced to the rear.

There was no strategy nor tactics in this battle; it was simply men standing up and giving and taking, and the one that stood the longest won the battle. The only strategy or tactics was the movement of Van Dorn attacking on the right flank and in the rear, and these moves were fatal to his success. Curtis's Army fought each man for himself. Every commander fought his own part of the battle to the best of his ability, and I think the feeling of all was that unless they won they would have to go to Richmond, as the enemy was in the rear, which fact made us desperate in meeting and defeating the continued attacks of the enemy. I sent for reinforcements once when the enemy was clear around my right flank and in my rear, and they sent me a part of the Eighth Indiana, two companies of the Third Illinois Cavalry, and a section of a battery. The battery fought ten minutes under a heavy fire. The four companies of the Eighth Indiana lined up alongside the Fourth Iowa, and stayed there fighting bravely until the end. The Third Illinois held my right flank. The officer who brought this force to me was Lieutenant Shields, of my own Regiment, who was acting as aid on Colonel Carr's staff. As he rode up to me to report the Eighth Indiana he halted alongside of me, and at the same instant both of our horses fell dead without a struggle – something very unusual. I was quick, and jumped clear of my horse, but Shields's horse fell upon him. I walked away, not thinking of Shields; but he called back to me and said, "Colonel, you are not going to leave me this way are you?" and I returned and helped him from under his horse. An examination of the two horses made the next day, showed that they must have been killed by the same bullet, which passed through their necks at the same place, killing them instantly.

A log house was used by us early in the morning as a temporary hospital. When my skirmishers fell back this log house was left in the lines of the enemy, and Hospital Steward Baker, of the Fourth Iowa, was left in charge of the wounded there. When General Price came up he asked him who those black-coated devils were, and when Baker told him there were only six hundred he did not believe him. He said no six hundred men could stand such attacks, and paid the Brigade a very high compliment for their fighting, and told Baker to give them his compliments.

I never returned to this Army, but many of the troops who fought so gallantly fought afterwards in Corps and Armies that I was connected with. My own Regiment went into battle with 548 rank and file present. Company B was on detailed service holding Pea Ridge, and had no casualties in line of battle. My Regiment was greatly reduced from sickness and men on furlough, but the bravery and steadiness with which those with me fought was a surprise and a great satisfaction to me. One-third of them fell, and not a straggler left the field. I had drilled the Regiment to most all kinds of conditions – in the open, in the woods – and many complained, and thought I was too severe, as many Regiments at the posts where they were stationed only had the usual exercises; but after this, their first battle, they saw what drilling, maneuvers, and discipline meant, and they had nothing but praise for the severe drilling I had given them. They never fell under my command again, but on every field that they fought they won the praise of their commanders, and General Grant ordered that they should place on their banners, "First at Chickasaw Bayou."

I have never thought that General Curtis has received the credit he was entitled to for this campaign and battle. With 12,000 men he traversed Missouri into Arkansas, living off the country, and showing good judgment in concentrating to meet Van Dorn and refusing to retreat when urged to do so at the conference at the log schoolhouse on the morning of the 7th. The night of the 7th I know some officers thought we ought to try to cut ourselves out to the East, Price being in our rear; but Curtis said he would fight where we were. He then had no knowledge of the condition of the enemy. On the morning of the 8th he brought General Siegel's two Divisions into the fight and concentrated on Price, whose fighting was simply to cover his retreat. General Curtis failed to reap the full benefit of the battle because Siegel went to Cassville, leaving only Davis's and Carr's Divisions on the field. We who took part in this campaign appreciate the difficulties and obstacles Curtis had to overcome, and how bravely and efficiently he commanded, and we honor him for it. So did General Halleck; but the Government, for some reason, failed to give him another command in the field, though they retained him in command of departments to the end of the war.

Letter of General Grenville M. Dodge to his Father on the Battle of Pea Ridge

St. Louis, Mo., April 2, 1862.DEAR FATHER: – I know there is no one who would like to have a word from me more than you. I write but little – am very weak from my wounds; do not sit up much; but I hope ere long to be all right again. Nothing now but the battle will interest you. It was a terrible three days to me; how I got through God only knows. I got off a sick bed to go to the fight, and I never got a wink of sleep for three days and three nights. The engagement was so long and with us so hot that it did not appear possible for us to hold our ground. We lacked sadly in numbers and artillery, but with good judgment and good grit we made it win. My officers were very brave. Little Captain Taylor would stand and clap his hands as the balls grew thick. Captain Burton was as cool as a cucumber, and liked to have bled to death; then the men, as they crawled back wounded, would cheer me; cheer for the Union; and always say, "Don't give up Colonel, hang to em;" and many who were too badly wounded to leave the field stuck to their places, sitting on the ground, loading and firing. I have heard of brave acts, but such determined pluck I never before dreamed of. My flag-bearer, after having been wounded so he could not hold up the colors, would not leave them. I had to peremptorily order him off. One time when the enemy charged through my lines the boys drove them back in confusion. Price fought bravely; his men deserved a better fate, but although two to one they could not gain much. Their artillery was served splendidly – they had great advantage over us in this. Mine run out of ammunition long before night and left me to the mercy of their grape and canister. Had I have had my full battery at night I could have whipped them badly. After the Fourth Iowa's ammunition gave out or before this all the other Regiments and Brigades had given way, leaving me without support, and when I found my ammunition gone I never felt such a chilling in my life. It is terrible right in the midst of a hot contest to have your cartridges give out. We had fired forty-two rounds, and had but a few left. I saved them and ceased firing, falling back to my supports. The enemy charged me in full force. I halted and they came within fifty feet. We opened on them such a terrible fire they fled. General Curtis rode into the field then and asked me to charge. This would have blanched anybody but an Iowa soldier. No ammunition and to charge! We fixed bayonets, and as I gave the order the boys cheered and cheered, swinging their hats in every direction. CHARGE! and such a yell as they crossed that field with, you never heard – it was unearthly and scared the rebels so bad they never stopped to fire at us or to let us reach them. As we marched back, now dark, nearly one-half the entire Army had got on the ground and the black-coats (Fourth Iowa) had got their fame up. The charge without ammunition took them all, and as we passed down the line the whole Army cheered us. General Curtis complimented us on the field, and what was left of the Fourth Iowa held their heads high that night, though a gloomy one for those who knew our situation. The next morning it fell to my lot to open the battle with my artillery again, and for one hour we poured it into them hot and heavy. We opened with thirty-two guns; they answered with as many, and such a roar you never heard. The enemy could not stand it and fled. Our whole army deployed in sight that morning and it was a grand sight with the artillery playing in open view. I had read of such things, but they were beyond my conception. This closed the battle and we breathed free. I escaped most miraculously. A shell burst right in front of me, and, tearing away my saddle holsters and taking off a large piece of my pants, never even scratched me. My clothes were riddled and I got a hit in the side that is serious, but did not think of it at the time.

Yours, etc.,G. M.THE BATTLE OF ATLANTA

Fought July 22, 1864A Paper Read Before New York CommanderyM. O. L. LBy Major-General Grenville M. DodgeCompanions:

On the 17th day of July, 1864, General John B. Hood relieved General Joseph E. Johnston in command of the Confederate Army in front of Atlanta, and on the 20th Hood opened an attack upon Sherman's right, commanded by General Thomas. The attack was a failure, and resulted in a great defeat to Hood's Army and the disarrangement of all his plans.

On the evening of the 21st of July, General Sherman's Army had closed up to within two miles of Atlanta, and on that day Force's Brigade of Leggett's Division of Blair's Seventeenth Army Corps carried a prominent hill, known as Bald or Leggett's Hill, that gave us a clear view of Atlanta, and placed that city within range of our guns. It was a strategic point, and unless the swing of our left was stopped it would dangerously interfere with Hood's communications towards the south. Hood fully appreciated this, and determined upon his celebrated attack in the rear of General Sherman's Army.

On the 22d of July, the Army of the Tennessee was occupying the rebel intrenchments, its right resting very near the Howard House, north of the Augusta Railroad, thence to Leggett's Hill, which had been carried by Force's assault on the evening of the 21st. From this hill Giles A. Smith's Division of the Seventeenth Army Corps stretched out southward on a road that occupied this ridge, with a weak flank in air. To strengthen this flank, by order of General McPherson I sent on the evening of the 21st one Brigade of Fuller's Division, the other being left at Decatur to protect our parked trains. Fuller camped his Brigade about half a mile in the rear of the extreme left and at right angles to Blair's lines and commanding the open ground and valley of the forks of Sugar Creek, a position that proved very strong in the battle. Fuller did not go into line; simply bivouacked ready to respond to any call.

On the morning of the 22d of July, General McPherson called at my headquarters and gave me verbal orders in relation to the movement of the Second (Sweeney's) Division of my command, the Sixteenth Corps, which had been crowded out of the line by the contraction of our lines as we neared Atlanta, and told me that I was to take position on the left of the line that Blair had been instructed to occupy and intrench that morning, and cautioned me about protecting my flank very strongly. McPherson evidently thought that there would be trouble on that flank, for he rode out to examine it himself.

I moved Sweeney in the rear of our Army, on the road leading from the Augusta Railway down the east branch of Sugar Creek to near where it forks; then, turning west, the road crosses the west branch of Sugar Creek just back of where Fuller was camped, and passed up through a strip of woods and through Blair's lines near where his left was refused. Up this road Sweeney marched until he reached Fuller, when he halted, waiting until the line I had selected on Blair's proposed new left could be intrenched, so that at mid-day, July 22d, the position of the Army of the Tennessee was as follows: One Division of the Fifteenth across and north of the Augusta Railway facing Atlanta; the balance of the Fifteenth and all of the Seventeenth Corps behind intrenchments running south of the railway along a gentle ridge with a gentle slope and clear valley facing Atlanta in front, and another clear valley in the rear. The Sixteenth Corps was resting on the road described, entirely in the rear of the Seventeenth and Fifteenth Corps, and facing from Atlanta. To the left and left-rear the country was heavily wooded. The enemy, therefore, was enabled, under cover of the forest, to approach close to the rear of our lines.

On the night of July 21st Hood had transferred Hardee's Corps and two Divisions of Wheeler's Cavalry to our rear, going around our left flank, Wheeler attacking Sprague's Brigade of the Sixteenth Army Corps at Decatur, where our trains were parked. At daylight, Stewart's and Cheatham's Corps and the Georgia Militia were withdrawn closer to Atlanta, and placed in a position to attack simultaneously with Hardee, the plan thus involving the destroying of the Army of the Tennessee by attacking it in rear and front and the capturing of all its trains corraled at Decatur. Hardee's was the largest Corps in Hood's Army, and according to Hood there were thus to move upon the Army of the Tennessee about 40,000 troops.

Hood's order of attack was for Hardee to form entirely in the rear of the Army of the Tennessee, but Hardee claims that he met Hood on the night of the 21st; that he was so late in moving his Corps that they changed the plan of attack so that his left was to strike the Seventeenth Corps. He was to swing his right until he enveloped and attacked the rear of the Seventeenth and Fifteenth Corps.

Hood stood in one of the batteries of Atlanta, where he could see Blair's left and the front line of the Fifteenth and Seventeenth Corps. He says he was astonished to see the attack come on Blair's left instead of his rear, and charges his defeat to that fact; but Hardee, when he swung his right and came out in the open, found the Sixteenth Corps in line in the rear of our Army, and he was as much surprised to find us there as our Army was at the sudden attack in our rear. The driving back by the Sixteenth Corps of Hardee's Corps made the latter drift to the left and against Blair, – not only to Blair's left, but into his rear, – so that what Hood declares was the cause of his failure was not Hardee's fault, as his attacks on the Sixteenth Corps were evidently determined and fierce enough to relieve him from all blame in that matter.

Historians and others who have written of the Battle of Atlanta have been misled by being governed in their data by the first dispatches of General Sherman, who was evidently misinformed, as he afterwards corrected his dispatches. He stated in the first dispatch that the attack was at 11 a. m., and on Blair's Corps, and also that General McPherson was killed about 11 a. m. The fact is, Blair was not attacked until half an hour after the attack upon the Sixteenth Corps, and McPherson fell at about 2 p. m. General Sherman was at the Howard House, which was miles away from the scene of Hardee's attack in the rear, and evidently did not at first comprehend the terrific fighting that was in progress, and the serious results that would have been effected had the attack succeeded.

The battle began within fifteen or twenty minutes of 12 o'clock (noon) and lasted until midnight, and covered the ground from the Howard House along the entire front of the Fifteenth (Logan's) Corps, the Seventeenth (Blair's) on the front of the Sixteenth (which was formed in the rear of the Army), and on to Decatur, where Sprague's Brigade of the Sixteenth Army Corps met and defeated Wheeler's Cavalry – a distance of about seven miles.