полная версия

полная версияLondon

By poetic license, quite pardonable when assumed by Austin Dobson or by Praed, we speak of the leisure of the eighteenth century. Where is it – this leisure? I can find it nowhere. In London City the sober merchant who walks so gravely on 'Change is an eager, venturesome trader, pushing out his cargoes into every quarter of the globe, as full of enterprise as an Elizabethan, following the flag wherever that leads, and driving the flag before him. He belongs to a battling, turbulent time. His blood is full of fight. He makes enormous profits; sometimes he makes enormous losses; then he breaks; he goes under; he never lifts up his head again; he is submerged – he and his, for the City has plenty of benevolence, but little pity. We are all pushing, struggling, fighting to get ahead. We cannot stop to lift up one that has fallen and is trampled under foot. In the City there stands behind us a Fury armed with a knotted scourge. Let us work, my brothers, let us never cease to work, for this is the terrible pitiless demon called Bankruptcy. If there is no leisure or quiet among the sober citizens, where shall we look for it? In the country? We are not here concerned with the country, but I have looked for it there and I cannot find it.

It was the dream of every tradesman not only to escape this fiend, but in fulness of time to retire from his shop and to have his own country-house; or, if that could not be compassed, to have a box three or four miles from town – at Stockwell, Clapham, Hoxton, or Bow, or Islington – whither he might drive on Saturday or other days, in a four-wheeled chaise. He loved to add a bow-window to the front, at which he would sit and watch the people pass, his wine before him, for the admiration and envy of all who beheld. The garden at the back, thirty feet long by twenty broad, he laid out with great elegance. There was a gravel-walk at each end, a pasteboard grenadier set up in one walk, and a sundial in the other. In the middle there was a basin with two artificial swans, over which he moralized: "Sir, I bought those fowls seven years ago. They were then as white as could be made. Now they are black. Let us learn that the strongest things decay, and consider the flight of time." He put weathercocks on his house-top, and when they pointed different ways he reflected that there is no station so exalted as to be free from the inconsistencies and wants of life.

His wife, of course, was a notable house-keeper. It is recorded of her that she would never employ a man unless he could whistle. So that when he was sent to draw beer, or to bottle wine, or to pick cherries, or to gather strawberries, by whistling all the time he proved that his mouth was empty, because you cannot whistle with anything in your mouth. She made her husband take off his shoes before going up-stairs; she lamented the gigantic appetites of the journeymen whom they had to keep "peck and perch" all the year round; she loved a pink sash and a pink ribbon, and when she went abroad she was genteelly "fetched" by an apprentice or one of the journeymen with candle and lantern.

The amusements and sights of London were the Tower, the Monument, St. Paul's and Westminster Abbey, the British Museum (after the year 1754, when it was first opened), the Royal Exchange, the Bank of England, Guildhall, the East India House, the Custom-house, the Excise Office, the Navy Office, the bridges, the Horse Guards, the squares, the Inns of Court, St. James's Palace, the two theatres of Drury Lane and Covent Garden, the Opera-house, Ranelagh, Sadler's Wells, Vauxhall, Astley's, the Park, the tea-gardens, Don Saltero's, Chelsea, the trials at the Old Bailey, the hangings at Newgate, the Temple Gardens, the parade of the Judges to Westminster Hall, the charity children at St. Paul's, Greenwich Fair, the reviews of the troops, the House of Lords when the King is present and the peers are robed, Smithfield, Billingsgate, Woolwich, Chelsea Hospital, Greenwich Hospital, and the suburbs. With these attractions a stranger could get along for a few days without much fear of ennui.

The London fairs – Bartholomew, Greenwich, Southwark, May Fair – no longer, of course, pretended to have anything to do with trade. They were simply occasions for holiday-making and indulgence in undisguised license and profligacy. They had bull and bear baiting, cock-fighting, prize-fighting, cudgel-playing – these of course. They also had their theatres and their shows and their jugglers. They had races of women, fights of women, and dancing of girls for a prize. They continued the old morris-dance of five men, Maid Marian and Tom Fool, the last with a fox-brush in his hat, and bells on his legs and on his coat-tails. They were fond of rope-dancing – in a word, the fairs drew together all the rascality of the town and the country around. May Fair was stopped in the year 1708, but was revived some years afterwards. Southwark Fair, which was opened by the Lord Mayor and sheriffs riding over the bridge through the borough, was not suppressed till 1763. The only good thing it did was to collect money for the poor prisoners of Marshalsea Prison. Bartholomew and Greenwich Fair continued till thirty or forty years ago.

The picturesqueness of the time is greatly due to the dress. We all know how effective on the stage or at a fancy ball is the dress of the year 1750. Never had gallant youth a better chance of displaying his manly charms. The flowered waistcoat tight to the figure, the white satin coat, the gold-laced hat, the ruffles and dainty necktie, the sword and the sword-sash, the powdered wig, the shaven face, the silk stockings and gold-buckled shoes – with what an air the young coxcomb advances, and with what a grace he handles his clouded cane and proffers his snuffbox! Nothing like it remains in this century of ours. And the ladies matched the men in splendor of dress, until the "swing swang" of the extravagant hoop spoiled all. Here comes one, on her way to church, where she will distract the men from their prayers with her beauty, and the women with her dress. She has a flowered silk body and cream-colored skirts trimmed with lace; she has light blue shoulder-knots; she wears an amber necklace, brown Swedish gloves, and a silver bracelet; she has a flowered silk belt of green and gray and yellow, with a bow at the side, and a brown straw-hat with flowers of green and yellow. "Sir," says one who watches her with admiration, "she is all apple blossom."

The white satin coat is not often seen east of Temple Bar. See the sober citizen approaching: he is dressed in brown stockings; he has laced ruffles and a shirt of snowy whiteness; his shoes have silver buckles; his wig is dark grizzle, full-bottomed; he carries his hat under his left arm, and a gold-headed stick in his right hand. He is accosted by a wreck – there are always some of these about London streets – who has struck upon the rock of bankruptcy and gone down. He, too, is dressed in brown, but where are the ruffles? Where is the shirt? The waistcoat, buttoned high, shows no shirt; his stockings are of black worsted, darned and in holes; his shoes are slipshod, without buckles. Alas! poor gentleman! And his wig is an old grizzle, uncombed, undressed, dirty, which has been used for rubbing shoes by a shoeblack. On the other side of the street walks one, followed by a prentice carrying a bundle. It is a mercer of Cheapside, taking some stuff to a lady. He wears black cloth, not brown; he has a white tye-wig, white silk stockings, muslin ruffles, and japanned pumps. Here comes a mechanic: he wears a warm waistcoat with long sleeves, gray worsted stockings, stout shoes, a three-cornered hat, and an apron. All working-men wear an apron; it is a mark of their condition. They are no more ashamed of their apron than your scarlet-coated captain is ashamed of his uniform.

Let us note the whiteness of the shirts and ruffles: a merchant will change his shirt three times a day; it is a custom of the City thus to present snow-white linen. The clerks, we see, wear wigs like their masters, but they are smaller. The varieties of wigs are endless. Those that decorate the heads of the clerks are not the full-bottomed wig, to assume which would be presumptuous in one in service. Most of the mechanics wear their hair tied behind; the rustics, sailors, stevedores, watermen, and river-side men generally wear it long, loose, and unkempt. There is a great trade in second-hand wigs. In Rosemary Lane there is a wig lottery. You pay sixpence, and you dip in a cask for an old wig. It may turn out quite a presentable thing, and it may be worthless. Here is a company of sailors rolling along armed with clubs. They are bound to Ratcliffe, where, this evening, when the men are all drinking in the taverns, there will be a press. Their hats are three-cornered, they wear blue jackets, blue shirts, and blue petticoats. Their hair hangs about their ears. Beside them marches the lieutenant in the new uniform of blue, faced with white.

Let us consider the private life of the people day by day. For this purpose we must not go to the essayists or the dramas. The novels of the time afford some help; books corresponding to our directories, almanacs, old account-books, are the real guides to a reconstruction of life as it was about the year 1750. From such books as these the following notes are derived.

The most expensive parts of the town were the streets round St. Paul's Church-yard, Cheapside, and the Royal Exchange. Charing Cross, Covent Garden, and St. James's lie outside our limits. Here the rent of a moderate house was from a hundred to a hundred and fifty guineas a year. In less central places the rents were not more than half as much. There were six or seven fire insurance offices. The premium for insurance on houses and goods not called hazardous was generally two shillings per cent. on any sum under £1000, half a crown on all sums between £1000 and £2000, and three and sixpence on all sums over £3000, so that a man insuring his house and furniture for £2500 would pay an annual premium of £4 7s. 6d.

The taxes of a house amounted to about half the rent. There was the land-tax of four shillings in the pound; the house-tax of sixpence to a shilling in the pound; the poor-rate, varying from one shilling to six shillings in the pound; the window-tax, which made you pay first three shillings for your house, and then, with certain exceptions, twopence extra for every window, so that a house of fourteen windows paid four and sixpence. In the year 1784 this tax was increased in order to take the duty off tea. The church-wardens' rate for repairing the church; the paving-rate, of one and sixpence in the pound; the watch; the Easter offerings, which had become optional; the water-rate, varying from twenty-four shillings to thirty shillings a year.

The common practice of bakers and milkmen was to keep a tally on the door-post with chalk. One advantage of this method was that a mark might be added when the maid was not looking. The price of meat was about a third of the present prices; beef being fourpence a pound, mutton fourpence halfpenny, and veal sixpence. Chicken were commonly sold at two and sixpence the pair; eggs were sometimes three and sometimes eight for fourpence, according to the time of year. Coals seem to have cost about forty shillings a ton; but this is uncertain. Candles were eight and fourpence a dozen for "dips," and nine and fourpence a dozen for "moulds;" wax-candles were two and tenpence a pound. For out-door lamps train-oil was used, and for in-doors spermaceti-oil. For the daily dressing of the hair, hair-dressers were engaged at seven shillings to a guinea a month. Servants were hired at register offices, but they were often of very bad character, with forged papers. The wages given were: to women as cooks, £12 a year; lady's-maids, £12 to £20; house-maids from £7 to £9; footmen, £14 and a livery. Servants found their own tea and sugar, if they wanted any. Board wages were ten and sixpence a week to an upper servant; seven shillings to an under servant. Every householder was liable to serve as church-warden, overseer for the poor, constable – but he could serve by deputy – and juryman. Peers, clergymen, lawyers, members of Parliament, physicians, and surgeons were exempted.

The principle of life assurance was already well established, but not yet in general use. There seem to have been no more than four companies for life assurance. The Post-office rates varied with the distance. A letter from London to any place not exceeding one stage cost twopence; under two stages, threepence; under eight miles, fourpence; under 150 miles, fivepence; above 150 miles, to any place in England, sixpence; to Scotland, sevenpence; to Ireland, sixpence; to America and the West Indies, a shilling; to any part of Europe, a shilling to eighteenpence. There was also a penny post, first set up in London by a private person. This had five principal offices. Letters or packets not exceeding four ounces in weight were carried about the City for one penny, and delivered in the suburbs for a penny more. There were no bank-notes of less than £20 before the year 1759; but when the smaller notes were issued, and came into general use, people very soon found out the plan of cutting them in two for safety in transmission by post.

Mail-coaches started every night at eight o'clock with a guard. They were timed for seven miles an hour, and the fare for passengers was fourpence a mile. A passenger to Bristol, for example, who now pays twenty shillings first-class fare and does the journey in two hours and a half, then paid thirty-three and fourpence, and took fourteen hours and a quarter. A great many of the mails started from the Swan with Two Necks, a great hostelry and receiving-place in Lad Lane. The place is now swept away with Lad Lane itself. It stood in the part of Gresham Street which runs between Wood Street and Milk Street.

The stage-coaches from different parts of London were innumerable, as were also the stage-wagons and the hoys. The coaches charged the passengers threepence a mile. Hackney-coaches ran for shilling and eighteenpenny fares. There were hackney-chairs. In the City there were regular porters for carrying parcels and letters.

There were nine morning papers, of which the Morning Post still survives. They were all published at threepence. There were eight evening papers, which came out three times a week. And there were three or four weekly papers, intended chiefly for the country.

The stamps which had to be bought with anything were a grievous burden. A pair of gloves worth tenpence – stamp of one penny; worth one and fourpence – stamp of twopence; above one and fourpence – stamp of fourpence. Penalty for selling without a stamp, £5. Hats were taxed in like manner. Inventories and catalogues were stamped; an apprentice's indentures were stamped; every newspaper paid a stamp of three halfpence. In the year 1753 there were seven millions and a half of stamps issued to the journals.

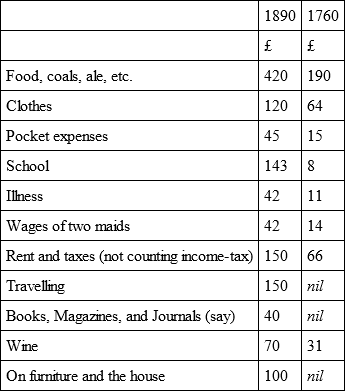

We have seen what it cost a respectable householder to pay his way in the time of Charles the Second. The following shows the cost of living a hundred years later. The house is supposed to consist of husband and wife, four children, and two maids:

Food, coals, candles, small beer (of which 12 gallons are allowed – that is, 48 quarts, or an average of one quart a day per head), soap, starch, and all kinds of odds and ends are reckoned at £3 12s. 5d. a week, or £189 18s. 8d. a year; clothes, including hair-dressing, £64; pocket expenses, £15 12s.; occasional illness, £11; schooling, £8; wages, £14 10s.; rent and taxes, £66; entertainments, wine, etc., £30 19s.: making a total of £400 a year.

If we take the same family with the same scale of living at the present day, we shall arrive at the difference in the cost of things:

A comparison of the figures shows a very considerable raising of the standard as regards comfort and even necessaries. It is true that the modern figures have been taken from the accounts of a family which spends every year from £1200 to £1400.

It may be remarked in these figures that schooling is extremely cheap, viz., £8 per four children, or ten shillings a quarter for each child. Therefore for a school-master to get an income of £250 a year, out of which he would have to maintain assistants, he must have 125 scholars. The "pocket expenses" include letters, and all for six shillings a week, which is indeed moderate. Entertainments, wine, etc., are all lumped together, showing that wine must be considered a very rare indulgence, and that small beer is the daily beverage. Tea is set down at two shillings a week. In the year 1728 tea was thirteen shillings a pound, but by 1760 it had gone down to about six shillings a pound, so that a third of a pound was allowed every week. This shows a careful measurement of the spoonful. Of course there was not as yet any tea allowed to the servants. Coals are estimated at £14 a year – two fires in winter, one in summer. Repairs to furniture, table-linen, sheets, etc., are set down at two shillings a week, or five guineas a year. Happy the household which can now manage this item at six times that amount.

It might be thought that by the middle of the last century the beverage of tea was universally taken in this country. This was by no means the case. The quantity of tea imported about this time amounted to no more than three-quarters of a pound per annum for every person in the three kingdoms, whereas it is now no less than thirty-five pounds for every head. It was, and had been for fifty years, a fashionable drink, and it had now become greatly in use – or, at all events, greatly desired – by women of all kinds. The men drank little of it; men in the country and working-men not at all. Its use was not so far general as to stop the discussion which still continued as to its virtues. In the year 1749 it was ten shillings a pound. In 1758 a pamphlet was written by an anonymous writer on the good and bad effects of drinking tea. We learn from this that the author is alarmed at the spreading of the custom of tea-drinking, especially by "Persons of an inferior rank and mean Abilities." "It may not," he says, "be altogether above the reach of the better Sort of Tradesmen's Wives and Country Dames. But nowadays Persons of the Lowest Class vainly imitate their Betters by striving to be in the fashion, and prevalent Custom hath introduced it into every Cottage, and every Gammer must have her tea twice a day." The latter statement is rank exaggeration, as the imports show.

Especially the author finds fault with afternoon tea. "It is very hurtful," he says, "to those who work hard and live low; when taken in company with gossips a dram too often follows; then comes scandal, with falsehoods, perversions, and backbitings: it is an expense which very few can afford; it is a waste of time which ought to be spent in spinning, knitting, making clothes for the children. Oh, I here with confusion stop, and know not how sufficiently to bewail my grief to you, delightful fair! who, by prevalent custom, are led into one of the worst of habits, rendering you lost to yourselves, and unfit for the comforts you were first designed. Be careful; be wise; refuse the bait; fly from a temptation productive of so many ills. You charming guiltless young ones, who innocently at home partake of this genteel regale, avoid the public meetings of low crafty gossips, who will use persuasions for you to drink tea with them and some others of their own stamp."

Another bad consequence of afternoon tea is that it induces the little tradesmen's wives, after selling something, to offer their customer tea, and after that a dram, and so vanish all the profits.

But the writer objects altogether to tea. He cannot find that it possesses any merits. The hot-water, the cream, and the sugar, he says, are responsible for all the good effects of tea-drinking. The tea itself is responsible for all the bad effects. He enumerates the opinions advanced by physicians. The learned Dr. Pauli, physician to the King of Denmark, shows that the virtues ascribed to it are local, and do not cross the seas into Europe. Men over forty, he thinks, should never use it, because it is a desiccative; the herb betony should be taken by them, because it has all the virtues and none of the vices of tea. Schroder and Quincey believed it good for every complaint; the learned Pechlin held that it is good for scorbutic cases, but thought that veronica and Paul's betony are just as good. Dr. Hunt enumerates many diseases for which its occasional use is good. Finally, the writer of the pamphlet concludes that tea will rapidly become cheaper; that it will then go out of fashion; and that it will be replaced by our own sage, which, he says, makes a much more wholesome drink, with hot-water, cream, and sugar.

But a far greater person than this anonymous writer set his face and the whole force of his authority and example against the drinking of tea. This was no other than John Wesley, who, in the year 1748, issued a "Letter to a Friend, concerning Tea." The following extracts give the practical part of the letter, omitting the very strange argument against tea-drinking based upon Scripture:

Twenty-nine years ago, when I had spent a few months at Oxford, having, as I apprehended, an exceeding good Constitution, and being otherwise in Health, I was a little surprised at some Symptoms of a Paralytick Disorder. I could not imagine what should occasion that shaking of my Hand; till I observed it was always worst after Breakfast, and that if I intermitted drinking Tea for two or three Days, it did not shake at all. Upon Inquiry, I found Tea had the same effect upon others also of my Acquaintance; and therefore saw, that this was one of its natural Effects (as several Physicians have often remarked), especially when it is largely and frequently drank; and most of all on Persons of weak Nerves. Upon this I lessened the Quantity, drank it weaker, and added more Milk and Sugar. But still, for above six and twenty Years, I was more or less subject to the same Disorder.

July was two Years, I began to observe, that abundance of the People in London, with whom I conversed, laboured under the same, and many other Paralytick Disorders, and that in a much higher Degree; insomuch that some of their Nerves were quite unstrung; their bodily Strength was quite decay'd, and they could not go through their daily Labour. I inquired, 'Are you not an hard Drinker?' And was answered by one and another, 'No, indeed, Sir, not I! I drink scarce any Thing but a little Tea, Morning and Night.' I immediately remembered my own Case; and after weighing the matter thoroughly, easily gathered from many concurring Circumstances, that it was the same Case with them.

I considered, 'What an Advantage would it be, to these poor enfeebled People, if they would leave off what so manifestly impairs their Health, and thereby hurts their Business also? – Is there Nothing equally cheap which they could use? Yes, surely: And cheaper too. If they used English Herbs in its stead (which would cost either Nothing, or what is next to Nothing), with the same Bread, Butter, and Milk, they would save just the Price of the Tea. And hereby they might not only lessen their Pain, but in some Degree their Poverty too…'

Immediately it struck into my Mind, 'But Example must go before Precept. Therefore I must not plead an Exemption for myself, from a daily Practice of twenty-seven Years. I must begin.' I did so. I left it off myself in August, 1746. And I have now had sufficient Time to try the Effects, which have fully answered my Expectation: My Paralytick Complaints are all gone: My Hand is as steady as it was at Fifteen: Although I must expect that, or other Weaknesses, soon: as I decline into the Vale of Years. And so considerable a Difference do I find in my Expence, that I can make it appear, from the Accounts now in being, in only those four Families at London, Bristol, Kingswood, and Newcastle, I save upwards of fifty Pounds a Year.

The first to whom I explained these Things at large, and whom I advised to set the same Example to their Brethren, were, a few of those, who rejoice to assist my Brother and me, as our Sons in the Gospel. A Week after I proposed it to about forty of those, whom I believed to be strong in Faith: And to the next Morning to about sixty more, intreating them all, to speak their Minds freely. They did so: and in the End, saw the Good which might insue; yielded to the Force of Scripture and Reason: And resolved all (but two or three) by the Grace of God, to make the Trial without Delay.