полная версия

полная версияAn Englishman's View of the Battle between the Alabama and the Kearsarge

The Kearsarge reached Cherbourg on the 14th, and her Captain only heard of Captain Semmes’ intention to fight him on the following day. Five days, however, elapsed before the Alabama put in an appearance, and her exit from the harbour was heralded by the English yacht Deerhound. The officer on watch aboard the Kearsarge made out a three-masted vessel steaming from the harbour, the movements of which were somewhat mysterious; after remaining a short time only, this steamer, which subsequently proved to be the Deerhound, went back into port; only returning to sea a few minutes in advance of the Alabama, and the French iron-clad La Couronne. Mr. Lancaster, her owner, sends a copy of his log to the Times, the first two entries being as follows:

“Sunday, June 19, 9 A. M. – Got up steam and proceeded out of Cherbourg harbour.

“10.30. – Observed the ‘Alabama’ steaming out of the harbour towards the Federal steamer ‘Kearsarge.’”8

Mr. Lancaster does not inform us why an English gentleman should choose a Sunday morning, of all days in the week, to cruise about at an early hour with ladies on board, nor does he supply the public with information as to the movements of the Deerhound during the hour and a half which elapsed between his exit from the harbour and the appearance of the Alabama. The preceding paragraph, however, supplies the omission.

THE ENGAGEMENTAt length the Alabama made her appearance in company with the Couronne, the latter vessel conveying her outside the limit of French waters. Here let me pay a tribute to the careful neutrality of the French authorities. No sooner was the limit of jurisdiction reached, than the Couronne put down her helm, and without any delay, steamed back into port, not even lingering outside the breakwater to witness the fight. Curiosity, if not worse, anchored the English vessel in handy vicinity to the combatants. Her presence proved to be of much utility, for she picked up no less than fourteen of the Alabama’s officers, and among them the redoubtable Semmes himself.

So soon as the Alabama was made out, the Kearsarge immediately headed seaward and steamed off the coast, the object being to get a sufficient distance from the land so as to obviate any possible infringement of French jurisdiction; and, secondly, that in case of the battle going against the Alabama, the latter could not retreat into port. When this was accomplished, the Kearsarge was turned shortly round and steered immediately for the Alabama, Captain Winslow desiring to get within close range, as his guns were shotted with five-seconds shell. The interval between the two vessels being reduced to a mile, or thereabouts, the Alabama sheered and discharged a broadside, nearly a raking fire, at the Kearsarge. More speed was given to the latter to shorten the distance, and a slight sheer to prevent raking. The Alabama fired a second broadside and part of a third while her antagonist was closing; and at the expiration of ten or twelve minutes from the Alabama’s opening shot, the Kearsarge discharged her first broadside. The action henceforward continued in a circle, the distance between the two vessels being about seven hundred yards; this, at all events, is the opinion of the Federal commander and his officers, for their guns were sighted at that range, and their shell burst in and over the privateer. The speed of the two vessels during the engagement did not exceed eight knots the hour.

At the expiration of one hour and two minutes from the first gun, the Alabama hauled down her colours and fired a lee gun (according to the statements of her officers), in token of surrender. Captain Winslow could not, however, believe that the enemy had struck, as his own vessel had received so little damage, and he could not regard his antagonist as much more injured than himself; and it was only when a boat came off from the Alabama that her true condition was known. The 11-inch shell from the Kearsarge, thrown with fifteen pounds of powder at seven hundred yards range, had gone clean through the starboard side of the privateer, bursting in the port side and tearing great gaps in her timber and planking. This was plainly obvious when the Alabama settled by the stern and raised the forepart of her hull high out of water.

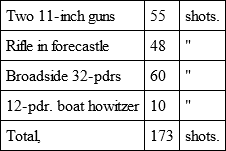

The Kearsarge was struck twenty-seven times during the conflict, and fired in all one hundred and seventy three (173) shots. These were as follows:

SHOTS FIRED BY THE KEARSARGE.

The last-named gun performed no part whatever in sinking the Alabama, and was only used in the action to create laughter among the sailors. Two old quarter-masters, the two Dromios of the Kearsarge, were put in charge of this gun, with instructions to fire when they received the order. But the two old salts, little relishing the idea of having nothing to do while their messmates were so actively engaged, commenced peppering away with their pea-shooter of a piece, alternating their discharges with vituperation of each other. This low-comedy by-play amused the ship’s company, and the officers good-humoredly allowed the farce to continue until the single box of ammunition was exhausted.

DAMAGE TO THE KEARSARGEThe Kearsarge was struck as follows:

One shot through starboard quarter, taking a slanting direction aft, and lodging in the rudder post. This shot was from the Blakely rifle.

One shot, carrying away starboard life-buoy.

Three 32-pounder shots through port bulwarks, forward of mizzen-mast.

A shell, exploding after end of pivot port.

A shell, exploding after end of chain-plating.

A 68-lb. shell, passing through starboard bulwarks below main rigging, wounding three men – the only casualties amongst the crew during the engagement.

A Blakely-rifle shell, passing through the engine-room sky-light, and dropping harmlessly in the water beyond the vessel.

Two shots below plank-sheer, abreast of boiler hatch.

One forward pivot port plank sheer.

One forward foremast-rigging.

A shot striking Launch’s toping-lift.

A rifle-shell, passing through funnel, bursting without damage inside.

One, starboard forward main-shroud.

One, starboard after-shroud main-topmast rigging.

One, main topsail tye.

One, main topsail outhaul.

One, main topsail runner.

Two, through port-quarter boat.

One, through spanker (furled).

One, starboard forward shroud, mizzen rigging.

One, starboard mizzen-topmast backstay.

One, through mizzen peak-signal halyards, which cut the stops when the battle was nearly over, and for the first time let loose the flag to the breeze.

This list of damages received by the Kearsarge proves the exceedingly bad fire of the Alabama, notwithstanding the numbers of men on board the latter belonging to our “Naval Reserve,” and the trained hands from the gunnery ship “Excellent.” I was informed by some of the paroled prisoners on shore at Cherbourg that Captain Semmes fired rapidly at the commencement of the action “in order to frighten the Yankees,” nearly all the officers and crew being, as he was well aware, merely volunteers from the merchant service.9 At the expiration of twenty minutes after the Kearsarge discharged the first broadside, continuing the battle in a leisurely, cool manner, Semmes remarked: “Confound them; they’ve been fighting twenty minutes, and they’re as cool as posts.” The probabilities are that the crew of the Federal vessel had learnt not to regard as dangerous the rapid and hap-hazard practice of the Alabama.

From the time of her first reaching Cherbourg until she finally quitted the port, the Kearsarge never received the slightest assistance from shore, with the exception of that rendered by a boiler maker in patching up her funnel. Every other repair was completed by her own hands, and she might have crossed the Atlantic immediately after the action without difficulty. So much for Mr. Lancaster’s statement that “the Kearsarge was apparently much disabled.”

SEMMES’ DESIGN TO BOARD THE KEARSARGEThe first accounts received of the action led us to suppose that Captain Semmes’ intention was to lay his vessel alongside the enemy, and to carry her by boarding. Whether this information came from the Captain himself or was made out of “whole cloth” by some of his admirers, the idea of boarding a vessel under steam – unless her engines, or screw, or rudder be disabled – is manifestly ridiculous. The days of boarding are gone by, except under the contingencies above stated; and any such attempt on the part of the Alabama would have been attended with disastrous results to herself and crew. To have boarded the Kearsarge, Semmes must have possessed greater speed to enable him to run alongside her; and the moment the pursuer came near her victim, the latter would shut off steam, drop astern in a second of time, sheer off, discharge her whole broadside of grape and canister, and rake her antagonist from stern to stem. Our pro-southern sympathizers really ought not to make their protegé appear ridiculous by ascribing to him such an egregious intention.

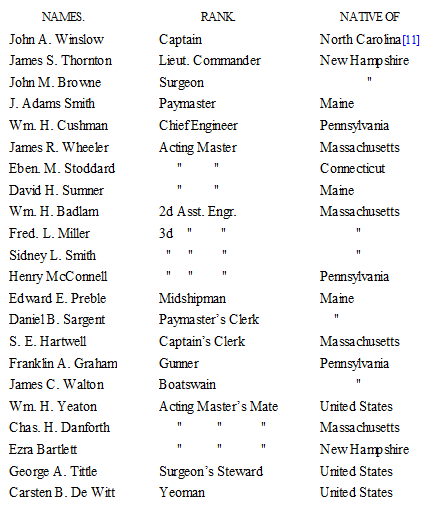

NATIONALITY OF THE CREW OF THE KEARSARGEIt has frequently been asserted that the major portion of the Northern armies is composed of foreigners, and the same statement is made in reference to the crews of the American Navy. The report got abroad in Cherbourg that the victory of the Kearsarge was due to her having taken on board a number of French gunners at Brest; and an admiral of the French Navy asked me in perfectly good faith whether it were not the fact. It will not, therefore, be out of place to give the names and nationalities of the officers and crew on board the Kearsarge during her action with the Alabama.

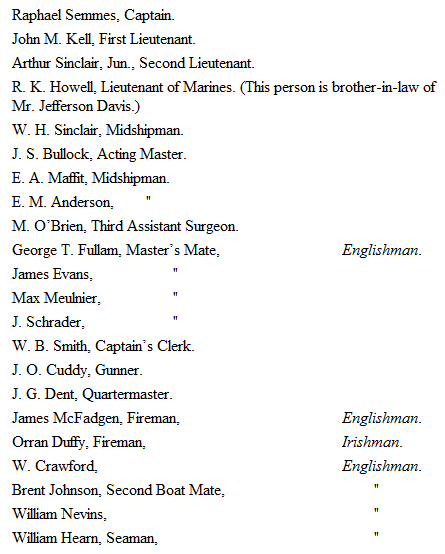

OFFICERS OF THE U.S.S. KEARSARGE, June 19, 1864.

11Captain Winslow has long been a citizen of the State of Massachusetts.

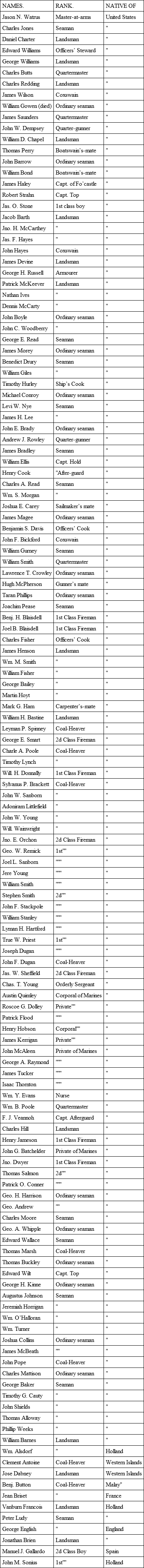

CREW OF THE U.S.S. KEARSARGE, June 19, 1864.

It thus appears that out of one hundred and sixty-three (163) officers and crew of the sloop-of-war Kearsarge, there are only eleven (11) persons foreign born.

The following is the Surgeon’s report of casualties amongst the crew of the Kearsarge during the action:

“U. S. S. S. Kearsarge,“Cherbourg, France,“Afternoon, June 19, 1864.“Sir – I report the following casualties resulting from the engagement this morning with the steamer ‘Alabama.’

John W. Dempsey, Quarter-gunner. Compound comminuted fracture of right arm, lower third, and fore-arm. Arm amputated.

William Gowen, Ordinary seaman. Compound fracture of left thigh and leg. Seriously wounded.

James McBeath, Ordinary seaman. Compound fracture of left leg. Severely wounded.

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

John M. Browne,Surgeon U. S. Navy.“Captain John A. Winslow,

“Comd’g U. S. S. S. Kearsarge, Cherbourg.”

All these men were wounded by the same shot, a 68-pounder, which passed through the starboard bulwarks below main-rigging, narrowly escaping the after 11-inch pivot-gun. The fuses employed by the Alabama were villainously bad, several shells having lodged in the Kearsarge without taking effect. Had the 7-inch rifle shot exploded which entered the vessel at the starboard quarter, raising the deck by its concussion several inches and lodging in the rudder-post, the action might have lasted some time longer. It would not, however, have altered the result, for the casualty occurred towards the close of the conflict. During my visit, I witnessed the operation of cutting out a 32-pounder shell (time fuse) from the rail close forward of the fore pivot 11-inch port; the officer in charge of the piece informed me that the concussion actually raised the gun and carriage, and, had it exploded, many of the crew would have been injured by the fragments and splinters.

Among the incidents of the fight, some of our papers relate that a 11-inch shell from the Kearsarge fell upon the deck of the Alabama, and was immediately taken up and thrown overboard. Probably no fight ever occurred in modern times in which somebody didn’t pick up a live shell and throw it out of harm’s way; but we may be permitted to doubt in this case – 5-second fuses take effect somewhat rapidly; the shot weighs considerably more than a hundred-weight, and is uncomfortably difficult to lay hold of. Worse than all for the probabilities of the story, fifteen pounds of powder – never more nor less – were used to every shot fired from the 11-inch pivots, the Kearsarge only opening fire from them when within eight hundred yards of the Alabama. With 15 pounds of powder and fifteen degrees of elevation, I have myself seen these 11-inch Dahlgrens throw three and a half miles; and yet we are asked to credit that, with the same charge at less than half a mile, one of the shells fell upon the deck of the privateer. There are eleven marines in the crew of the Kearsarge: probably the story was made for them.

THE REPORTED FIRING UPON THE ALABAMA AFTER HER SURRENDERCaptain Semmes makes the following statement in his official report:

“Although we were now but 400 yards from each other, the enemy fired upon me five times after my colours had been struck. It is charitable to suppose that a ship of war of a Christian nation could not have done this intentionally.”

A very nice appeal after the massacre of Fort Pillow, especially when coming from a man who has spent the previous two years of his life in destroying unresisting merchantmen.

The Captain of the Kearsarge was never aware of the Alabama having struck until a boat put off from her to his own vessel. Prisoners subsequently stated that she had fired a lee-gun, but the fact was not known on board the Federal ship, nor that the colours were hauled down in token of surrender. A single fact will prove the humanity with which Captain Winslow conducted the fight. At the close of the action, his deck was found to be literally covered with grape and canister, ready for close quarters; but he had never used a single charge of all this during the contest, although within capital range for employing it.

THE FEELING AFTER THE BATTLEThe wounded of the two vessels were transferred shortly after the action to the Naval Hospital at Cherbourg. I paid a visit to that establishment on the Sunday following the engagement, and found the sufferers lying in comfortable beds alongside each other in a long and admirably ventilated ward on the first floor. Poor Gowen, who died the following Tuesday, was in great pain, and already had the seal of death upon his face. James McBeath, a young fellow of apparently twenty years, with a compound fracture of the leg, chatted with much animation; while Dempsey, the stump of his right arm laid on the pillow, was comfortably smoking a cigar, and laughing and talking with one of the Alabama crew, in the bed alongside him. The wounded men of the sunken privateer were unmistakably English in physiognomy, and I failed to discover any who were not countrymen of ours. I conversed with all of them, stating at the outset that I was an Englishman like themselves, and the information seemed to open their hearts to me. They represented themselves as very comfortable at the hospital, that every thing they asked for was given to them, and that they were surprised at the kindness of the Kearsarge men who came to visit the establishment, when they were assured by their own officers before the action that foul treatment would only be shown them in the event of their capture. Condoling with one poor fellow who had his leg carried away by a shell, he remarked to me, “Ah, it serves me right! they won’t catch me fighting again without knowing what I’m fighting for.” “That’s me too,” said another poor Englishman alongside of him.

The paroled prisoners (four officers) on shore at Cherbourg, evinced no hostility whatever to their captors, but were always on the friendliest of terms with them. All alike frequented the same hotel in the town (curiously enough – “The Eagle,”) played billiards at the same café, and bought their pipes, cigars, and tobacco from the same pretty little brunette on the Quai du Port.

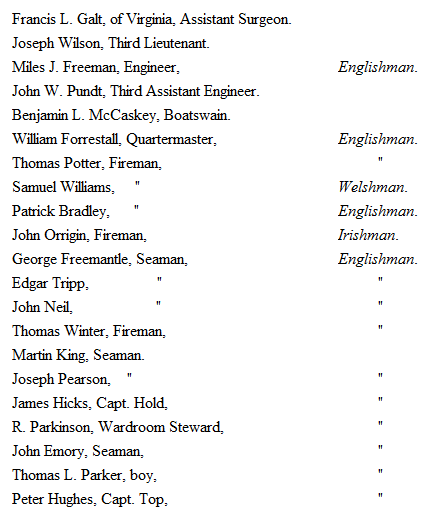

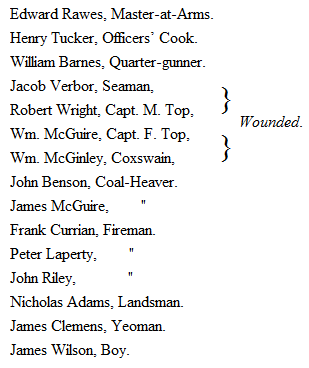

The following are the names of the officers and crew of the Alabama, saved by the Kearsarge:

(All the above belonged to the Alabama when she first sailed from the Mersey, and John Neil, John Emory, and Peter Hughes belong to the “Royal Naval Reserve.”)

Seamen. – William Clark, David Leggett, Samuel Henry, John Russell, John Smith, Henry McCoy, Edward Bussell, James Ochure, John Casen, Henry Higgin, Frank Hammond, Michael Shields, David Thurston, George Peasey, Henry Yates.

Ordinary Seamen. – Henry Godsen, David Williams, Henry Hestlake, Thomas Watson, John Johnson, Match Maddock, Richard Evans, William Miller, George Cousey, Thomas Brandon.

Coxswains. – William McKenzie, James Broderick, William Wilson.

These men, almost without exception, are subjects of Her Majesty the Queen. There were also three others, who died in the boats, names not known.

The following are those reported to have been killed or drowned:

The above all belonged to the original crew of the Alabama.

The Deerhound carried off, according to her own account, forty-one; the names of the following are known:

The last four belong to the “Royal Naval Reserve.”

MOVEMENTS OF THE ENGLISH YACHT DEERHOUNDThat an English yacht, one belonging to the Royal Yacht Squadron, and flying the White Ensign, too, during the conflict, should have assisted the Confederate prisoners to escape after they had formally surrendered themselves, according to their own statement, by firing a lee-gun, striking their colours, hoisting a white flag, and sending a boat to the Kearsarge – some of which signals must have been witnessed from the deck of the Deerhound, is most humiliating to the national honour. The movements of the yacht early on Sunday morning were as before shown, most suspicious; and had Captain Winslow followed the advice and reiterated requests of his officers when she steamed off, the Deerhound might now have been lying not far distant from the Alabama. Captain Winslow however, could not believe that a gentleman who was asked by himself “to save life” would use the opportunity to decamp with the officers and men who, according to their own act, were prisoners-of-war. There is high presumptive evidence that the Deerhound was at Cherbourg for the express purpose of rendering every assistance possible to the corsair; and we may be permitted to doubt whether Mr. Lancaster, the friend of Mr. Laird, and a member of the Mersey Yacht Club, would have carried Captain Winslow and his officers to Southampton if the result of the struggle had been reversed, and the Alabama had sent the Kearsarge to the bottom.

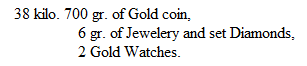

The Deerhound reached Cherbourg on the 17th of June, and between that time and the night of the 18th, boats were observed from the shore passing frequently between her and the Alabama. It is reported that English gunners come over from England purposely to assist the privateer in the fight; this I heard before leaving London, and the assertion was repeated to me again at Havre, Honfleur, Cherbourg, and Paris. If this be the fact, how did the men reach Cherbourg? On the 14th of June, Captain Semmes sends his challenge to the Kearsarge through Monsieur Bonfils, stating it to be his intention to fight her “as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements.” Two full days elapse, during which he takes on board 150 tons additional of coal, and places for security in the Custom House the following valuables:

What then became of the pillage of a hundred merchantmen, the chronometers, etc., which the Times describes as the “spolia opima of a whole mercantile fleet?” Those could not be landed on French soil, and were not: did they go to the bottom with the ship herself, or are they saved?

Captain Semmes’ preparations are apparently completed on the 16th, but still he lingers behind the famous breakwater, much to the surprise of his men. The Deerhound arrives at length, and the preparations are rapidly completed. How unfortunate that Mr. Lancaster did not favour the Times with a copy of his log-book from the 12th to the 19th of June inclusive!

The record of the Deerhound is suggestive on the morning of that memorable Sunday. She steams out from behind the Cherbourg breakwater at an early hour, – scouts hither and thither, apparently purposeless – runs back to her anchorage – precedes the Alabama to sea – is the solitary and close spectator of the fight whilst the Couronne has the delicacy to return to port, and finally – having picked up Semmes, thirteen of his officers and a few of his men – steams off at fullest speed to Southampton, leaving the “apparently much-disabled” Kearsarge (Mr. Lancaster’s own words) to save two-thirds of the Alabama’s drowning crew struggling in the water.

An English gentleman’s yacht playing tender to a corsair! No one will ever believe that Deerhound to be thorough-bred.

CONCLUSIONSuch are the facts relating to the memorable action off Cherbourg on the 19th of June, 1864. The Alabama went down riddled through and through with shot; and, as she sank beneath the green waves of the Channel, not a single cheer arose from the victors. The order was given, “Silence, boys,” and in perfect silence this terror of American commerce plunged to her last resting place.

There is but one key to the victory. The two vessels were, as nearly as possible, equals in size, speed, armament and crew, and the contest was decided by the superiority of the 11-inch Dahlgren guns of the Kearsarge, over the Blakely rifle and the vaunted 68-pounder of the Alabama, in conjunction with the greater coolness and surer aim of the former’s crew. The Kearsarge was not, as represented, specially armed and manned for destroying her foe; but is in every respect similar to all the vessels of her class (third-rate) in the United States Navy. Moreover, the large majority of her officers are from the merchant service.

The French at Cherbourg were by no means dilatory in recognizing the value of these Dahlgren guns. Officers of all grades, naval and military alike, crowded the vessel during her stay at their port; and they were all eyes for the massive pivots and for nothing else. Guns, carriages, even rammers and sponges, were carefully measured; and, if the pieces can be made in France, many months will not elapse before their muzzles will be grinning through the port-holes of French ships-of-war.

We have no such gun in Europe as this 11-inch Dahlgren, but it is considered behind the age in America. The 68-pounder is regarded by us as a heavy piece; in the United States it is the minimum for large vessels; whilst some ships, the “New Ironsides,” “Niagara,” “Vanderbilt,” etc., carry the 11-inch in broadside. It is considered far too light, however, for the sea-going ironclads, although throwing a solid shot of 160 pounds; yet it has made a wonderful stir on both sides of the Channel. What, then, will be thought of the 15-inch gun, throwing a shot of 480 pounds, or of the 200-pound Parrot, with its range of five miles?

We are arming our ironclads with 9-inch smooth-bores and 100-pounder rifles, whilst the Americans are constructing their armour-ships to resist the impact of 11 and 15-inch shot. By next June, the United States will have in commission the following ironclads:

These, too, without counting six others of “second class,” all alike armed with the tremendous 15-inch, and built to cross the Atlantic in any season. But it is not in ironclads alone that America is proving her energy; first, second and third-rates, wooden built, are issuing constantly from trans-Atlantic yards, and the Navy of the United States now numbers no less than six hundred vessels and upwards, seventy-three of which are ironclads.