полная версия

полная версияThe Churches of Paris, from Clovis to Charles X

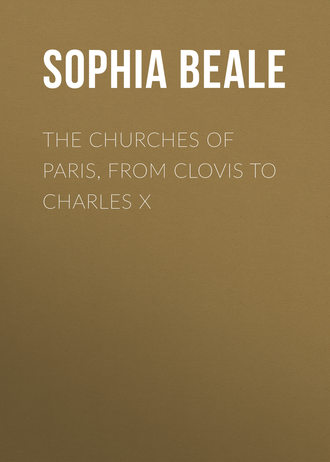

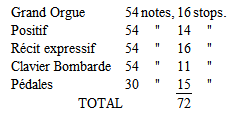

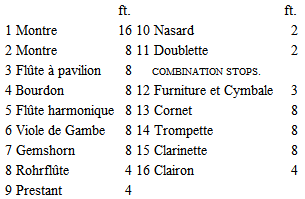

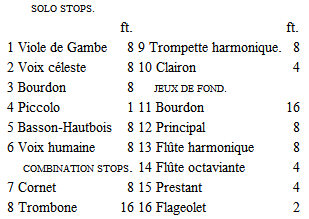

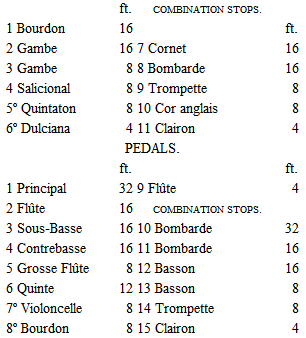

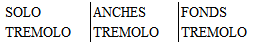

It may interest musicians to know the composition of the S. Eustache organ, and as many of the stops are French, I may as well give them in their original names. It has four manuals, and 72 stops; 4356 pipes and 20 pedals.

1ST MANUAL. – GREAT ORGAN.

2ND MANUAL. – CHOIR ORGAN.

3RD MANUAL. – SWELL ORGAN.

4TH MANUAL. – SOLO ORGAN.

COMBINATION STOPS FOR THE SWELL.

1 Tonnerre.

2 Tirasse du 1er clavier sur le pédalier.

3 Tirasse du 2me clavier sur le pédalier.

4 Tirasse du 3me clavier sur le pédalier.

5 Tirasse du 4me clavier sur le pédalier.

6 Réunion du mécanisme des jeux du 1er clavier sur le levier pneumatique.

7 Accouplement du 2me clavier sur le 1er.

8 Accouplement du 3me clavier sur le 1er, à l'unisson.

9 Accouplement du 4me clavier sur le 1er.

10 Accouplement du 4me clavier sur le 3me.

11 Accouplement du 3me clavier à l'octave grave sur le 1er clavier.

12 Forte général.

13 Introduction des jeux de combinaisons du pédalier.

14 Introduction des jeux de combinaisons du 1er clavier.

15 Introduction des jeux de combinaisons du 2me clavier.

16 Introduction des jeux de combinaisons du 4me clavier.

17 Expression sur le 3me clavier récit.

No one should omit visiting S. Eustache on S. Cecilia's day (November 22), when a grand mass is always performed, with full orchestra, in aid of the Society of Musicians; and indeed, any Sunday the music is quite well worth hearing, and the ceremonial is the finest in Paris. At the same time much has been lost by the substitution of the Roman for the Parisian rite, which took place in 1876. In the former, two acolytes swing the censers; in the latter, four or six acolytes standing in a row threw them up on high six times, the last time catching them while kneeling on one knee. As has been said, the grand effect of this use can never be forgotten by those who saw it.

The church owes the new marble pavement to its good curé l'abbé Simon, one of the heroes of the Commune, and, almost, one of its victims. So much has been related (and with justice) against the Communards, that an incident connected with S. Eustache ought not to be forgotten. The day the abbé Simon was arrested he had three thousand francs in his pocket, which were destined to pay for the pavement of the choir. Of course upon his arrival at the prison they were given up to the police, and were not restored when the curé was released through the intervention of his chères paroissiennes, les Dames de la Halle, who went en masse to demand his freedom. On Easter Monday, however, Raoul Rigault's secretary went to the sacristry, asked M. Simon if the money had been returned, and finding that it had not, he left the church, to return in an hour's time, with the three thousand francs intact.

In the south transept is a little Gothic statue of S. John, and on the wall is a sad memorial of the names of all the hostages who suffered death under the Commune, headed by the archbishop (Darboy) and the curé of the Madeleine, Duguerry, who was formerly curé of S. Eustache.

S. Eustache, like most large churches, looks grandest in the evening, when the altar is ablaze with lights, and long vistas fade away into the darkness; but under all conditions it is a splendid church, a mass of harmonious colouring from floor to ceiling. At the evening services during Lent, it is seen to advantage; or again on Christmas Day at vespers, when it is resplendent with lights; those curious and unchurchlike glass chandeliers filled with candles, and clusters of gas jets round the walls.

Another great day is Good Friday, when Rossini's "Stabat Mater" is performed. It is always beautifully rendered, but for three-fourths of the crowd which assembles – and the church is always crammed – for most of the people it is a mere performance. So is the midnight mass on Christmas Day. Religious enthusiasm carries one away upon one or two occasions; the sentiment is exquisite; the emotions which are aroused are of the purest, and we feel almost that we are by the veritable manger listening to the heavenly Host: "Glory to God in the Highest." But alas! human beings are but mortal; and so upon experience we find that the crowds who attend the mass do so mainly as a pastime before the réveillon; that is the function of the night; eating and drinking, junkettings and merrymakings; and just a little church-going to fill up the time until the hour of feasting commences. Cardinal Manning in his wisdom saw this many years ago, and stopped the practice of saying midnight mass, a measure he probably regretted as much as any of us; for apart from its being a very ancient custom, it is a most poetic idea, appealing strongly to our best emotions and our most vivid imagination.

SAINT-FRANÇOIS XAVIER

Until quite lately, the only church in Paris dedicated to the memory of the great Jesuit was the little chapel belonging to the Missions Étrangères in the Rue de Bac. The first stone was laid in 1683 by the archbishop of Paris, in the name of the king. It is a double chapel with a flight of steps leading from the lower to the upper church.

SAINTE-GENEVIÈVE (LE PANTHÉON)

As we walk up the Rue Soufflot and see the great domed Panthéon facing us in its Classic glory, it is difficult to realise that the space occupied by the modern building is but a small portion of what was formerly the domain of the important abbey of S. Geneviève belonging to the Augustinian canons. When the religious orders were suppressed in France, Paris contained nine abbeys: S. Geneviève, S. Victor, belonging to the Augustins; S. Germain des Prés to the Benedictines; Val des Grâce to the nuns of S. Benedict; Port-Royal, Pantemont, l'Abbaye aux Bois, and S. Antoine to the Cistercian nuns; and the Cordelières to the order of the Poor Clares. An inspection of a pre-Revolution map of the city shows us that a large part of it was swallowed up by these abbeys and other monastic lands and properties.

The foundation of the abbey of S. Geneviève was due to the desire of Clovis to celebrate his victory over the Visigoths in the plains of Vouillè. Having overrun a great part of Gaul, and annexed it to the kingdom of the Franks, what was more natural than that he should offer his thanks for robbery, violence, and slaughter, by the building of a church upon the hill overshadowing his Palais des Thermes? He dedicated it to S. Peter and S. Paul, and put it under the charge of some monks who were succeeded later on by secular canons, and eventually in the 12th century, by regular canons of S. Augustin. Clovis died ere the church was terminated, but Queen Clotilde was able to carry the work on, and it became the resting place of both sovereigns, as well as of the children of Clodomir, who were done to death by their loving relatives after the manner of some modern Africans. In the 11th century, the church was put under the patronage of S. Geneviève in consequence of the numberless miracles performed at her tomb, for the maid of Nanterre had been laid to rest in this church. The legend of S. Geneviève is picturesque in the extreme, affording endless subjects for the artist, as witness the wall paintings in the modern church. Born in 421 at Nanterre, a little village situated upon the plain over which the fort of Mt. Valérien now frowns, she was employed, as are many of her compatriots of the present day, in tending sheep. A graceful, if somewhat affected picture by Guérin, represents her with a distaff in her hands. When about seven years old, S. Germain, bishop of Auxerre, passed through Nanterre on his way to Britain. A crowd assembled to receive the good bishop's blessing, and among them were S. Geneviève and her parents. La pucelette was already famed for her piety and humility, and S Germain, wise man, had no sooner cast his eyes upon her than he became aware of her future glory; and finding that she desired to be a handmaiden of Christ, he hung round her neck a small coin marked with the symbol of the cross, thus consecrating her to God's service. Many were the miracles which she wrought by prayer, even in her childhood; as for instance, when her mother, being struck blind for boxing her little Saintship's ears, recovered her sight through the prayers of the daughter. Some say that Geneviève prayed for her hasty parent after a year and nine months had elapsed; but surely it is better to believe that the prayers were unanswered for that length of time, than that the daughter, whose intercession was so efficacious, should have omitted to help her mother for so many months.

At fifteen, Geneviève renewed her vows, but remained with her parents until their death. She then took up her abode with an old kinswoman in Paris, where, from her piety and devotion, she became the subject of disputes between those who venerated her as a saint, and others who considered her sanctity and benevolence mere hypocrisy and sham piety. And so it came about that at night, when she kept her vigils, the arch enemy, not content with putting into the hearts of men the desire to slander and vilify the godly maiden, set himself to worry her, by extinguishing her candle. But she had a tinder-box in her faith and prayer, and so she was never left in darkness. This is a favourite subject of the old artists; one frequently sees the Saint holding her taper, while a demon is blowing it out, sometimes using a pair of bellows, as at the doorway of S. Germain l'Auxerrois, S. Nicholas, and other French churches; and it is obvious that the legend grew out of the promise that God never leaves those in darkness who pray for light. So, too, the holding up of the re-kindled taper in the face of the fiend, and his consequent flight, symbolises the Light of the World chasing away evil. Another legend relates that when a storm overtook her and some friends on their way to S. Denis, and blew out their tapers, an Angel descended to relight them in answer to Geneviève's prayers.

The Saint was a sort of early Jeanne d'Arc, inasmuch as she delivered the city from its enemies; but Geneviève depended only upon her prayers; and yet, simply by these means, she caused the Huns, who were besieging Paris under Attila, to flee. On another occasion, when the city was invested by Childéric, she took command of some boats which were sent up the river to Troyes for succour, and brought them back laden with provisions. When the city was taken, Geneviève was treated with great respect by Childéric, and it was through her influence that Clovis and his wife, Clotilde, were converted to Christianity, and the first Christian church was erected in Paris.74 Geneviève died at the ripe old age of eighty-nine, and was buried in what was then called the church of SS. Peter and Paul; and it was in consequence of her miracle-working tomb that the patronage of the church was given over to her, the Apostles falling into complete oblivion. Among these miracles was a cessation of a terrible visitation of the plague called the mal ardent, which raged in Paris in the reign of Louis le Gros; hence the dedication of a church to S. Geneviève-des-Ardents, situated near the cathedral, and long since destroyed.

Most painters of modern times have depicted the Saint as a shepherdess, somewhat after the Chelsea china pattern, and a few have given her the suggestiveness of the nymphs of Boucher. Watteau's is a charming picture, but the graceful maiden scarcely comes up to our ideal of the pious little peasant girl of Nanterre. Guérin's is pure and refined, if somewhat affected, but one feels inclined to hail our old friend with the fiend behind her puffing or blowing the bellows as a more worthy reading of the character of S. Geneviève. In the church of S. Merri there is a very curious picture representing the maid surrounded by her sheep, and enclosed by a circle of huge stones after the manner of those at Stonehenge.

The legend of feeding the besieged Parisians is said to be the origin of the pain bénit of the Paris churches, a custom peculiar to the old Parisian rite, and almost the only one kept up since that use was superseded by the Roman, some few years since. This blessed bread is a large brioche offered by some of the parishioners, and brought into church in procession during the offertory. It is usually piled up on a stage and decorated with flowers and lights, the whole being carried on the shoulders of acolytes. Preceded by the beadle and donor, it is taken to the altar and sprinkled with holy water; some prayers are said, the donor is presented with a pax to kiss, and the procession then returns to the sacristy, where the bread is cut up and put into baskets, which are then carried round the church, and the brioche distributed among the congregation. One often sees strangers refuse this, thinking it something peculiarly popish; indeed, I was once assured by a friend that he had been offered the Sacrament, "which of course he had refused." But we may be certain that if the pain bénit were considered so exceedingly holy, promiscuous strangers would not get the chance of partaking of it. It rather figures a sort of amicable meal after the manner of the early Agapæ, and is a very pretty ceremony; besides, it is always refreshing to witness any little peculiarity in ritual, instead of the dull uniformity which recent papal decrees have enforced over western Europe.

In the 9th century S. Geneviève became the patron of the abbey; and some of the capitals of the church of that period are now in the court of the École de Beaux-Arts. In the 13th century the church was rebuilt, but gradually falling into decay, it was condemned in the reign of Louis XV., and demolished in 1801-7 to make way for the Rue Clovis. When the crypt was destroyed a large quantity of stone coffins, medals, pottery, shields and lances of Gallo-Roman and Mérovingian workmanship were found.

The early capitals mentioned above are rude in treatment, and the personages, Adam and Eve, and other Old Testament worthies, are coarse, but the scraps of ornament are quaint, and the carving of the foliage is vastly superior to that of the figures. The crypt of the church was the largest of any in Paris, and being the burial place of so many holy and regal persons, was interesting in the extreme; but to the men of the 18th century what mattered it that 13th century work should be swept away? The street was required as a short cut, a deviation of five minutes more or less had to be rectified; and so all that remains of the abbey church is its tower. But from the ruins many precious fragments were saved. The stone coffin of S. Geneviève was carried off to S. Étienne hard by, and there enveloped in a gorgeous shrine; which, besides being a work of art, had the advantage of being portative, and so could be marched about when processioning was resorted to as a remedy for city troubles. In the Statistique Monumentale de Paris, published by Albert Lenoir, may be seen some plates representing this motley crew of fragments. Portions of stone coffins, sculptured with crosses and monograms, were sent to the museum of the Petits-Augustins, but do not seem to have survived the dissolution of the collection; they were similar to those at the Hôtels de Cluny and Carnavalet.

The reliquary of the Saint was in the form of a church, and was executed by order of the abbot, Robert de la Ferté-Milon, in 1242. The craftsman was one of the most cunning goldsmiths of the city, Bonnard. It contained 193 marks of silver and 7-1/2 marks of gold; and kings, queens, and commoners vied with each other to cover it with precious stones. Marie de' Medici crowned the front with a mass of diamonds; and Germain Pilon was engaged to sculp a group of four women standing upon a marble pedestal to support the châsse. This graceful work of art was all that was saved in 1793: being of wood it was of little value to a starving and poverty-stricken mob. Or, had the municipality any reverence for it as an art treasure? Certain it is that, whereas the reliquary was melted up into coin, and the jewels sold, the part which was really the most precious was saved, and is now in the Renaissance Museum of the Louvre. But in spite of the value and beauty of the châsse, the Conventionel Grégoire, in his report, gives 21,000 livres only as the sum obtained by its destruction.

Some of the monuments of the church were saved; that of the Cardinal François de la Rochefoucault, abbot of S. Geneviève, and High Almoner of France, who died in 1645, sculptured by Philippe Buister, being placed in the chapel of the Hospital for Incurable Women, of which he was the founder. The statue of Clovis, renewed in the 12th century, is now at S. Denis, owing to the accident of its having been replaced in the 17th century by a superior one in white marble, which was destroyed in 1793.75 Another tomb, that of a chancellor of Notre-Dame de Noyon, who died in 1350, is now in the École des Beaux-Arts. The monument of René Descartes was less fortunate, for, after having been transferred to the museum of the Petits-Augustins, it was dismembered, and dispersed or destroyed; but the remains of the great philosopher were re-buried at S. Germain des Prés.

Some of the conventual buildings remain and form part of the Lycée Henri IV. The tower is Romanesque at the base and pointed at the upper stories – 14th and 15th century respectively. The cloisters and refectory form part of the school buildings, but they have been much modernized. The latter is an elegant structure of the 13th century, and now serves as the school chapel. In the sacristry is a large stone statue of the patroness (13th century) which formerly formed part of the central pillar of the principal doorway of the abbey church; it represents her with a demon on one shoulder blowing out her candle, and an Angel on the other relighting it. What was formerly the library is a series of galleries upon the plan of a cross, with a cupola at the intersections. It is no longer used for this purpose, all the books having been placed in the new building on the other side of the square.

"Contiguous to the Sorbonne church there stands, raising its neatly-constructed dome aloft in air, the Nouvelle Eglise Ste. Geneviève, better known by the name of the Panthéon. The interior presents, to my eye, the most beautiful and perfect specimen of Grecian architecture with which I am acquainted. In the crypt are the tombs of the French warriors. From the gallery running along the bottom of the dome, the whole a miniature representation of our S. Paul's, you have a sort of panorama of Paris, but not a favourable one. The absence of sea-coal fume strikes you very agreeably, but I could not help thinking of the superior beauty of the panorama of Rouen from the heights of St. Catherine."76 This "perfect specimen of Grecian architecture" owes its birth, it is said, to Madame de Pompadour; and if this be so, it must have been one of the last of that lady's contributions to art, as she died in April, 1764, the foundation stone being laid in the following September. It is curious how artistic the French kings' handmaidens were, and, with the exception of the daughters of the house of Medici, how little we owe to the queens in the way of fine works of art. Whether this particular handmaiden obliged the king to decide upon the rebuilding of the old church, which had been tumbling into decay for a long period, or whether it was the king's fright lest he should fall ill again if he did not propitiate the Saint who had cured him of a sinking fever, it is impossible to decide. Very likely it was the king's own fears. He had all but died at Metz; he had appealed to the patroness of Paris; she had answered his prayers, somewhat unwisely perhaps, in the interest of his hapless subjects; and in sheer gratitude, thus proving himself far more honest than many a holier and more godly man, he decided that the much-talked-of church should be set going, and that it should be worthy of the maid of Nanterre. And so it is. Soufflot was the architect, and his design is one of the happiest of its class. But what a strange life the church has had! And what an extraordinary jumble of Christianity and philosophy the great dome has witnessed! Emblems of the Roman Republic and the religion of Christ stand side-by-side. Cardinals repose in the crypt by the side of Voltaire and Jean-Jacques. At one time masses are said for the repose of the souls of defunct Christians; at another, funeral allocutions are delivered by laymen. And the chopping and changing about! Scarcely finished in 1791, the Constitutional Assembly decreed that the new church should become a Temple of Fame, and be known as the Panthéon. The cross was taken down from the summit of the dome, the inscription, Aux grands hommes, la Patrie reconnaissante, was substituted for D.O.M. Sub invocatione sanctae Genovefae sacrum; and under the peristyle was written: Panthéon français, l'an III. de la Liberté. The words of the report issued, describing the changes to be adopted in the building, are in the accustomed grandiloquent language of the First Republic: … "en un moment où tout doit contribuer à renforcer dans l'ame des citoyens toutes les sensations que l'enthousiasme de la liberté fait puiser dans l'amour de la Patrie, &c." Mirabeau, Marat, and Lepelletier Saint-Fargeau were laid to rest in the crypt.

One of Napoleon's first acts was to decide that "l'église Sainte-Geneviève serait rendue au culte, conformément à l'intention de son fondateur, sous l'invocation de Sainte Geneviève, patronne de Paris." But it was also to preserve the destination ascribed to it by the Constituante, that of being the burial-place of senators, officers of state, dignitaries, officers of the Legion of Honour, and of citizens who had rendered eminent service to their country. The divine offices were to be conducted by the canons of Notre-Dame, and to this end they were increased by six members. With the restoration of Louis XVIII. all homage to "great men" disappeared, and the old inscription was restored. Baron Gros was commissioned to paint the dome with the Apotheosis of S. Geneviève, a work described by an old writer in not over flattering terms: "On one of the cupolas of the dome, which is surrounded by a colonnade of Corinthian pillars, is painted the Apotheosis of St. Geneviève. Her saintship is in the costume of a shepherdess, breathing all peace, all happiness, all immortality. Nothing of earth is in her composition. Beside her is Louis XVIII. and little winged angels. They are very busy – the angels – in scattering flowers about the saint. Above her is Louis XVI. and his queen, as elegant as she was upon the threshold of Versailles, and Louis XVII., all surrounded by celestial glory. Before her are the persons the most illustrious of each race; Clovis, who looks very savage; St. Clotilde, very pretty; Charlemagne, very heroic; and St. Louis and Queen Margarite, who look very pious… The floor of this temple, incrusted with various-coloured marble, is very remarkable and very beautiful. It is exclusively occupied by Voltaire and Rousseau, at opposite extremities. Who would have thought that these two champions of Infidelity, who were refused Christian burial, would one day have assigned to their remains the first church of France, and one of the first in Christendom, as their mausoleum? I wonder if Jean-Jacques, in his prophetic visions, foresaw this? Why did they not lay them at the side of each other, that we might all learn how vain are the jealousies, the petty competitions and animosities of men so soon to come to this appointed and unavoidable term of all human contentions? It was once the custom of these old countries to multiply a man by burying him piecemeal, – his heart at Rouen and his legs in Kent, – because the world was then on short allowance of heroes; but modern times have reversed this practice; and Bonaparte has laid up together a whole batch of them in the basement of this church, for eternity, as you lay up potatoes in your cellar for winter. Here are the names graven overhead in a catalogue, on the marble, of men famous for giving counsel to the Emperor (who never took any) in the Senate, and of men who gained a great deal of celebrity by having their brains knocked out on the fields of Austerlitz and Marengo. When Marat was deified by the Convention he was interred here in 1793, and in 1794 he was disinterred and undeified, and then thrown into his native element, the common sewer, in the Rue Montmartre – to purify him."77