Полная версия

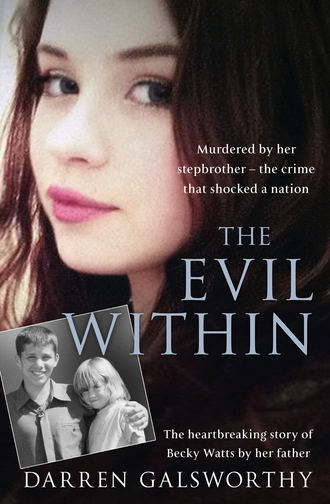

The Evil Within: Murdered by her stepbrother – the crime that shocked a nation. The heartbreaking story of Becky Watts by her father

Copyright

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published as Becky by HarperElement 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Darren Galsworthy 2016

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Front cover photograph © Enterprise News and Pictures

Picture section © Darren Galsworthy (unless stated otherwise)

A catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library

Darren Galsworthy asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008179618

Ebook Edition © March 2016 ISBN: 9780008179625

Version: 2018-09-13

Dedication

For my beautiful Bex

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

1. Becky

2. The fight

3. Happy families

4. My boy

5. Becky’s teenage years

6. Shauna

7. The day that changed our lives

8. The search

9. The arrests

10. Saying goodbye

11. The funeral

12. Limbo

13. The trial begins

14. The trial continues

15. Verdict and sentencing

16. Aftermath

Afterword by Anjie Galsworthy

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

Foreword

I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors. When I was growing up, my father would teach me all about the wonders of nature, and there was nothing I enjoyed more than pulling on my wellies and running outside to explore. To me, it was the only place where you could be free and let your imagination run wild. An open clearing would become a kingdom, a wooded area would turn into a secret, magical garden. A large tree would become my castle for the day. When I had children of my own, I taught them that their imagination was limitless. As they grew up to love the outdoors too, I rediscovered it through their eyes. For me, that was part of the magic of having children.

I still love taking long walks, but these days I tend to be alone. It gives me a good opportunity to think and to set the world to rights. I never feel completely alone anyway – everywhere I look I can see memories of my daughter Becky, from when she was a toddler, clutching her microscope to examine the bugs on the leaves, to when she was a teenager, examining her nail polish as we walked together, talking about her hopes and dreams.

Becky was at the beginning of adulthood when she was cruelly taken from us. She was just starting to figure out who she was, and who she wanted to be in the future. She was growing into a beautiful young woman, with a wicked sense of style and an attitude to match.

These days, I take a long walk whenever I want to feel her presence around me again. I often stroll slowly along the familiar winding lanes and sit down by the edge of a pond, enjoying the film reel of memories as they play out in my head. It’s there that I usually have one of my many one-sided conversations with Becky.

‘Hello, Bex. I hope you’re happy and safe, wherever you are. I hope you’re with my nan and she’s showing you all the love she showed me when I was your age. I wish you were with me so much. I miss everything about you – your laugh, your sense of humour, even the way you would make fun of me all day long.

‘I miss trying to embarrass you with my “dad dancing”. I even miss the practical jokes you used to play on me – like the time you waited until I fell asleep on the couch and then you painted me with as much make-up as you could find. I wondered why the man at the door was looking at me so strangely when I greeted him, but when I heard you giggling from your room I knew instantly that you had something to do with it. I was horrified when I looked in the mirror and saw my red lips and bright blue eyelids – but you thought it was hilarious, and the sound of your laughter was enough to make everyone smile.

‘I miss having fun with you when you were a little girl, scrunching up my face into all sorts of shapes just to make you collapse into giggles, baking cupcakes with you in the kitchen, and reading to you in bed. My favourite part of the day was always watching you fall asleep then kissing you goodnight.

‘Bex, I even miss the rows we used to have. We were so alike, we used to rub each other up the wrong way, but we’d always end up rolling around with laughter. I miss the way you used to hurl yourself at me when you came in, winding me in the process. I miss you pulling my right arm around you and cuddling in. You could stay like that for hours, and I used to thank my lucky stars that you still wanted to do that, even when you were a teenager.

‘Not an hour goes by that I don’t think about you, Bex. From the moment I open my eyes to the moment I rest my head on my pillow at night, I see you. I see you in your room on your phone, I see you messing about with your friends at the front gate, I see you in our living room, cuddled up watching a film – you are everywhere. In a way, I’m glad because I don’t ever want to forget anything about you.

‘I try very hard not to think of the way you were taken from us, but it’s difficult. All I ever wanted to do was protect you, and I’ve tortured myself that I wasn’t there for you on that fateful day.

‘I loved you so much, Becky – and you knew it too. You knew how to wind me around your little finger. I couldn’t even tell you off for being naughty without telling you that I loved you first. I didn’t want you to have any doubt about how loved you were. You are still loved so much – not just by me, but by your friends and the whole family. Now that you’re gone there is a huge hole in our hearts.

‘I try not to focus on our loss; instead I think about all the amazing memories we made together. I used to worry about you not making friends easily, but now I’m actually grateful that you didn’t, because I became both your dad and your friend, and I will always treasure the time we spent together.

‘So for now, until we meet again, my princess, I just close my eyes and imagine you running around with your brown hair – which always shimmered red when the sun caught it – a big smile on your face and a lot of love in your heart. Your laughter could cheer me up even on a dark day. And one day, I know I’m going to hear that laughter again. Lots of love, Dad x’

Chapter 1

Becky

MONDAY, 23 FEBRUARY 2015

Appeal over missing schoolgirl: Concern is mounting over the disappearance of Bristol schoolgirl Becky Watts. The 16-year-old was last seen by her stepmother, Anjie Galsworthy, four days ago after she returned to her home at Crown Hill, St George’s, following a night at a friend’s house. Mrs Galsworthy says she saw Becky at around 11.15 a.m. on Thursday and chatted with her before heading out. Becky’s family and friends are growing increasingly worried as her disappearance is out of character. Her boyfriend Luke had been expecting to see her that day, but she didn’t respond to his texts. Becky’s mobile phone and laptop are missing too, but it appears she took no cash, clothes, makeup or anything else that might suggest she was going away for any length of time. Today, her father, Darren Galsworthy, and grandmother, Pat Watts, made a heartfelt public appeal for her return. Mr Galsworthy said: ‘Becky, we just want you to come home. You’re in no trouble at all – we just want to make sure you are OK. If you can, please give us a call or a text to let us know you are safe. We all love you and want you back home with us.’ Police are working with the family. They’ve released a photo and description of the missing girl and a social media campaign is under way, with the hashtag #FindBecky.

The first time I peered down at my baby daughter Becky, my heart melted. She was a proper bundle of joy and cute as a button. As she gazed up at me from her cot, blinking rapidly to try to take in her new surroundings, I couldn’t help but fall for her. At 6 pounds 12 ounces she was tiny, but I soon discovered that she had a good set of lungs for a newborn and could silence a whole room with her cries.

I adored Becky from that first moment, even though my feelings were tinged with uncertainty because I wasn’t sure if she was really my child. Her mother and I had been in an on–off relationship that was veering towards ‘off’ at the time she was conceived. But as Becky grew up, she became more and more like her old man – so much so that it startled both of us at times. Her big hazel eyes were the same as mine, and as she got older she developed a lot of my mannerisms. The only difference between us was the fact that she was far better looking! I called her ‘my beautiful Bex’ because, to me, Becky really was beautiful – inside and out.

I was born and bred in Bristol and have lived here all my life. Some parts of the city aren’t pretty, as I well know because I’ve made my home in some of the roughest bits, but in Bristol I have a strong sense of belonging. Bristol folk are some of the kindest, most genuine and supportive people you will ever meet, and I am proud of the city’s brilliant community spirit. I simply can’t imagine living anywhere else.

I was the first child in my family, born on New Year’s Eve 1963, when the Beatles were at number one with ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. I waited until 11 p.m. to make an appearance, so my parents, John and Sue Galsworthy, were staring down at my scrunched-up face as the clock struck midnight and everyone else across the country was welcoming in the New Year.

The next day, they brought me back from Southmead Hospital to their two-bedroom terraced house in Easton, Bristol. At that time Easton was one of the most deprived areas in the South West and it was multicultural, which was quite rare in those days. My family were among the only white people on our estate. Life in the 1960s in Bristol was quite tough for working-class people like us, and we had to struggle to make ends meet. My dad worked long hours as a machinist for a nuclear and defence engineering company, and my mum worked in a leather factory then later became an auxiliary nurse at an old people’s home.

My little brother Lee was born on 15 August 1966, when I was two and a half. We shared a room and at first I quite enjoyed having a younger brother, but as he grew older he became a bit gobby, always getting himself into trouble with the other kids on our estate. Because I was the older one, I had to jump in to protect him, and I eventually got a reputation for enjoying a fight – all thanks to Lee!

The 1970s was the decade of strikes, which led to power cuts and huge piles of rat-infested rubbish on the streets because the bin men weren’t collecting it any more. The economy was prone to inflation – it seemed as if every single time you went to the shops, prices had gone up. This led to workers demanding higher wages, which the government didn’t want to pay, and as a result the unions started to call for all-out strikes. Three-day working weeks were introduced as businesses were only allowed to use electricity for three consecutive days each week, while there were regular power cuts for home users. This meant that the inside of our house was as freezing cold as the outside during the winter months – we had ice on the inside of the windows. I was taught to bake bread at school because the bakers were on strike, like everyone else, and I got in the habit of nicking coal whenever I spotted it just so we could light the fire at night to keep warm. Huddled together by candlelight in the evenings, Lee and I thought it was great fun – but, of course, we were young and didn’t have any responsibilities. I imagine it was quite different for our parents, who had two kids to feed and keep warm.

My dad was the head of our household and extremely strict, as many fathers were back then. It wasn’t uncommon to receive a beating with his belt if we were naughty. Sometimes if my brother was bad I’d be punished too, and vice versa, which didn’t seem fair. Teachers were also allowed to beat pupils in those days. We were often hit with a bat, like a wooden paddle, in primary school, and when we got to secondary school a cane was used. I was quite an emotional kid, and it didn’t take much to make me cry. When the teacher asked me if I wanted a telling off or the bat, I always chose the bat because I was used to getting beatings at home and knew I could take them. Strange as it may sound, to me words hurt more.

My mother wasn’t the most maternal person and never stood up for my brother or me. She worked morning or evening shifts at the leather factory, and we would often come home from school to find her passed out on the sofa after drinking gin during the afternoon. I didn’t realise she was an alcoholic until much later. I didn’t really know what that was then, but I knew it was useless trying to get any sense out of her when she’d been drinking. Since she wasn’t capable of making dinner, I learned to make food for Lee and me from an early age. At first it was just sandwiches I made from the food parcels donated to poor families by people at the local church. Later, I learned to make simple meals like egg and chips or sausage and chips, and I often made dinner for my father too. He was always in a better mood if there was food on the table ready for him when he returned home from work.

Money was incredibly scarce for our family. We didn’t have a fridge – just a wooden cupboard in the back garden where we kept our milk. We were lucky enough to have a black-and-white television, but in those days there were only two channels and it took five minutes to warm up after you switched it on. Lee and I didn’t have any toys but we made our own entertainment, playing in rubbish dumps and skips and hanging out with other kids around the estate. We never received any presents at Christmas from our parents – they didn’t celebrate Christmas at all – but we knew that when we went to visit May, our grandmother on my mum’s side, we would get spoilt.

Nan always had time for her grandkids and would be sure to feed us up because she knew we weren’t getting enough to eat at home. I loved her dearly, and some of my best childhood memories involve her. On Tuesdays and Thursdays she picked us up to take us into town on the bus and she always had a bar of chocolate for us to share. When I was eight, she gave me the best present ever: my first proper bike. It was a bronze-coloured Panther bike, which was second-hand but still the best thing I’d ever seen. For years, Nan was the only source of love and affection Lee and I had, what with Mum’s drinking and Dad’s temper dominating life at home. I don’t want this to sound like a sob story because others had it much tougher than me, but let’s just say it wasn’t the most comfortable, stable start in life.

My parents split up when I was nineteen, and my dad then married Denise in September 1985. Through Denise I instantly gained two stepbrothers – Kevin, who was three, and Ben, who was one. My father and Denise went on to have four children together – Sarah, Sam, Joe and Asa. I bonded with them pretty quickly, and to this day they remain among my closest friends. Dad mellowed with age and became a much gentler man than the one I had grown up with, so that today we have a good relationship. My mum died in 2010, from pneumonia, and sadly we never became close.

I had already left the family home by the time Dad remarried. When I was eighteen I moved out to live with my girlfriend, Angela Holloway, who was a year younger than me. We later got hitched, but the marriage only lasted three years. It was a case of far too much, too young, for both of us.

During the period when I was married, I used to babysit for the kids of some friends of mine, Mark and Verna West. One day, I arrived just as their other babysitter was leaving, and the minute I set eyes on her I felt as though I’d been struck by lightning. She was so gorgeous I could barely speak to introduce myself.

‘I’m Anjie,’ she told me.

‘Darren.’

I felt electricity running all the way through my body, and I just couldn’t take my eyes off her. She kept glancing at me too, while we chatted about everyday things like the kids we were looking after, where we lived, that kind of thing. It was the strangest feeling, but I just knew there was something special about her. It was as if kindness and light shone out of her, and it was the most powerful sensation I had ever felt.

However, I was married to Angela Holloway at the time and, after we got divorced, I heard that Anjie was seeing someone else, then in 1986 I heard she was pregnant. I just assumed it was a case of bad timing and nothing was going to happen between us. I never forgot about her, though.

I was twenty-two when Angela and I broke up. I had a few girlfriends after that but nothing too serious. I was concentrating on my career, and that didn’t really leave me much time for a relationship. At the age of sixteen I had done a youth-training scheme in tyre-fitting and car maintenance, at eighteen I was taken on for an engineering apprenticeship at a company that made precast concrete products, and by my mid-twenties I was working as a sheet metal engineer for a firm called City Engineering. I was very serious about making enough money to have a better standard of living than I’d had when I was growing up. I wanted a decent place to live and enough food to put on the table, and I was prepared to put in the graft to earn them.

When I was twenty-nine, I met a girl called Tanya Watts, who was twenty-two and worked as a carer in an old-folks’ home. She was with some friends in a local pub, and we got chatting, as you do. We seemed to get on well, I bought her a few drinks, and suddenly, almost before I knew it, we were in a relationship. We moved in to a flat in Cadbury Heath soon after meeting and settled into a life of working, going to the pub at the weekend, and taking the occasional holiday. Her mum, Pat, paid for us to go to Pembrokeshire for a week the first year we were together.

We didn’t ever get married because the relationship always had problems, but I was excited when our son Danny was born on 19 February 1995. He came into the world at Southmead Hospital – same as his old man. When I held him for the first time I couldn’t help but laugh because he was covered in fine black hair and looked like a baby chimp! I was thrilled to see that he looked exactly the same as me in my baby photographs. It was a very proud moment. I was overwhelmed that I had a son, and I swore there and then that I would always love and protect him.

Danny and I bonded instantly and I threw myself into being a dad, but I was working such long hours as an engineer that my time with him became sacred. Meanwhile, my relationship with Tanya was deteriorating fast. We began to fight about anything and everything, hurling hurtful comments at each other, often continuing rows into the early hours of the morning. I tried to shield baby Danny from as much of it as possible, but living with Tanya was getting harder and harder for me.

Sometimes she kicked me out of the flat after a row, and one night in January she told me I’d have to sleep in my car. I didn’t sleep a wink all night long, and as I lay there shivering, I realised that Tanya and I being together was doing more harm than good. I couldn’t see any way we could make it work in the long term, but at the same time I didn’t want to leave my baby son, so I kept trying.

We got into a pattern: we’d have a big row, Tanya would kick me out, then I’d go back a few days later to see my boy and we’d try again. Danny was two years old before I eventually decided enough was enough. Tanya kicked me out after yet another row, and I moved into a flat my friend was subletting while he worked away from home. Two weeks later, Tanya called and asked when I was coming back, and I told her that the answer was never.

I was relieved that at last the decision had been made, but it was horrible being away from Danny. I missed him terribly. He was just at the stage of chatting away in a mixture of baby words and real words and I couldn’t bear to miss any of it, so I persuaded Tanya to let him come to stay with me on the weekends. Hand-overs were difficult because the communication between us was in tatters by then, although I tried my hardest to be civil for Danny’s sake. I paid my child maintenance, but still we often argued over money. It was difficult, to say the least, but Danny was precious and I treasured every single moment with him.

It was a tough time all round. The only thing keeping me going was the thought of seeing Danny at the end of each week. I worked all the hours under the sun to make ends meet. My father didn’t teach me much, but he did teach me the importance of hard work. I’ve always been a hardworking man and I’m proud of that.

One Saturday night in October 1997, I was in my flat, with Danny asleep in bed, when Tanya knocked on the door. I opened it, expecting her to start an argument with me about something, but instead she was smiling and friendly. I’d had a few drinks by that stage and decided to let her in. One thing led to another and we ended up sleeping together. She left before the sun came up, and as soon as I woke I regretted what we had done. It was sending out all the wrong signals because, as far as I was concerned, the relationship was totally over.

I tried to forget about it and move on, but a few months later one of Tanya’s female friends – she didn’t say who she was – rang me while I was at work.

‘Tanya’s pregnant,’ she blurted out. ‘And you’re the father.’

‘And how on earth am I the father, then?’ I demanded. ‘Of course it’s not my bloody child. She’s just trying to mug me off.’

When I saw her next, as I was dropping Danny home the following weekend, she noticed my eyes wander down to her growing baby bump. I said I didn’t believe it was mine.

‘It is your baby,’ she shrugged. ‘You’ll see.’

The months passed and I carried on having Danny at the weekends, as usual. Then, on 3 June 1998, I got a call at work from one of Tanya’s friends to tell me that she had given birth to a baby girl. I thought it was nice that Danny would have a sister, but I still didn’t believe the baby was mine, even though she was born roughly nine months after Tanya and I’d had that one-night reunion.

The day after the birth, I drove Danny up to the Bristol Royal Infirmary so he could meet his little sister. Tanya had decided she was to be called Rebecca, Becky for short. Danny was excited about it, and I didn’t want him to miss out.