Полная версия

Larry’s Party

In a brilliantly lit bookstore in Manchester Larry found a book about hedges. It was in a bargain bin. Over a hundred colored, badly bound illustrations instructed the reader on the varieties and uses of hornbeam, butcher’s broom, laurel, cypress, juniper, lime, whitethorn, privet, holly, hawthorn, yew, dwarf box, and sycamore. How to plant them, how to nourish them, and tricks to keep them trim and tidy. How certain plants can be intertwined with others to make a sturdier or more beautiful hedge; plashing, this artful mixing of varieties was called. Larry studied the pages of Hedges of England and Scotland while the coach made its way south, heading toward Devon and Cornwall. In a mere day or two he was able to distinguish from the bus window the various species. This easy mastery surprised him, but then he remembered how he had won the class prize back in his floral arts course, that one of his teachers had commented on his excellent memory and another on his observation skills.

The clues to identifying hedges lay in the density and distribution of thicket, the hue of the green foliage, and the form of the developing leaves. He pronounced the names out loud as he spotted them, and then he wrote them on the inside of the book’s cover. He’d forgotten in the last two or three years that he was like this, always wanting to know things he didn’t need to know.

Dorrie, seated next to him on the coach, had fallen into the doldrums. She was homesick, she said. And tired of being stuck with all these old biddies. Their teasing at breakfast, always the same old thing, it was getting on her nerves, it was driving her bananas.

Each day was greener than the one before. One morning, halfway through the two-week tour, Arthur leapt from his seat at the front of the coach and excitedly pointed out a long sloping field of daffodils. “Didn’t I promise you, ladies and gents, that we’d be seeing daffodils on this holiday!” Everyone crowded to the windows for a look, everyone except for Mrs. Edwards, who was sleeping soundly with her head thrown straight back and her mouth open.

Dorrie pulled her diary out of her purse and wrote a single word on the page: “Daffodils.” (Years later when Larry came across the little book, he found three-quarters of the pages empty. “Daffodils” was the final entry.)

On the same day that they saw the daffodils Dr. Edwards bought Larry a pint of beer – this was in a pub early in the evening, a ten minutes’ rest stop – and said, out of the blue, “Our sabbatical leave doesn’t actually come up for another two years, but Mrs. Edwards has a problem with prescription drugs, also over-the-counter drugs. It’s a terrible business and getting worse, and so it seemed a good idea for us to get away.”

Larry peered into the remains of his dark foamless beer. He wished he were standing at the other end of the polished bar where the New Zealand and Australian couples were laughing loudly and arguing about how many miles it was to the hotel in Bath. Full of rivalrous good feeling, they liked to joke back and forth, shouting out about the relative merits of kiwis and kangaroos, soccer teams and politics. Larry was drawn to their good spirits, but felt shy in their presence, especially the men with their bluff, hearty conviviality, so different from Dr. Edwards’ sly, stiff questioning.

And yet Dr. Edwards, Robin, had seen fit to divulge his unhappy situation to Larry, to a stranger young enough to be his son.

“She hides them. They’re so small, you see. The pills. So easy to conceal.”

“Is she addicted to them?” This seemed to Larry a foolish, obvious question, but he felt a response of some kind was required.

“Yes, addicted, of course. She can’t help herself.”

“That’s terrible. It must be awfully difficult –”

“It’s heartening to see a couple like yourself,” Dr. Edwards said, steering the conversation in a more positive direction. “Just starting off in your life, free as a pair of birds.”

Larry swallowed down the rest of his beer. “We’re going to have a baby,” he said. “My wife, I mean.”

Dr. Edwards received the news politely: “I see,” he said. His fingers twirled a button on his raincoat.

“Maybe you’ve noticed that she’s not feeling all that great,” Larry said. “In the mornings especially.”

“I hadn’t actually noticed.”

“Morning sickness.”

He and Dorrie had agreed that the baby was going to be a secret, at least until they got back home and told their families. It startled him now to hear the words running so loosely out of his mouth: the baby. He’d scarcely thought of “the baby” since leaving home. It was hard enough to remember he was a husband, much less a father. He had to remind himself, announcing the fact to the mirror every morning as he blinked away the ghost of his father’s face. Husband, husband – one husband face pushing its way through another, blunt, self-satisfied, but never quite losing its look of surprise.

Lately he’d found he could dispel the face by filling up his head with the greenness of hedgerows. It was like switching channels. Holly, lime, whitethorn, box, a string of names like the chorus of a popular song. He let their shrubby patterns press down on his brain, their smooth stiff dignified shapes and rounded perfection.

“We were going to wait and get married in June. But then – this happened – so here we are. March.”

He could see he had lost Dr. Edwards’ interest, and certainly the opportunity to offer comforting remarks about Mrs. Edwards’ problems.

“Well,” Dr. Edwards said. He spoke briskly now, more like a sportscaster than a sociology teacher. “Time we got back on the coach or we’ll be left behind.”

“We’ve been going together for over a year,” Larry explained. He hung on to his beer glass. “We’d already talked about marriage. We’d already made up our minds, so this didn’t make any real difference.”

Dr. Edwards’ face had pulled into a frown. He put his hand on Larry’s shoulder, bearing down heavily with his fingertips. “About my wife?” he said. “I’d appreciate it if you regarded what I said as confidential.”

“Why?” Dorrie yelled at Larry. “Why would you go and tell that old professor jerk about us?”

They were in Devon, in the town of Barnstable, the King’s Inn. Their room was at the front of the hotel overlooking a street of busy shops.

“I don’t know,” Larry said.

“We fucking decided we weren’t going to tell anyone. And don’t tell me not to say fuck. I’ll say fuck all I fucking want.”

“It just came out. We were talking, and it slipped out.”

“My mother doesn’t even know. My own mother. And you had to go and tell that jerk. Did you honestly think he wasn’t going to tell that snot of a wife? My ‘condition’ she said to me, I shouldn’t be having a beer in my ‘condition.’ And now the whole bus is going to know. I’ll bet you anything they already do.”

“What does it matter?”

“We’re on our honeymoon, that’s why it matters. We’re the lovey-dovey honeymooners, for God’s sake, only now the little bride person is pregnant.”

“No one even thinks like that anymore.”

“Oh yeah? What about your mother and father? They think like that.”

“How do you know what they think?”

“They think no one’s good enough for their precious little Larry, that’s what they think. Especially girls dumb enough to go and get themselves preggo.”

“They’ll get used to it.”

“Like it’s my fault. Like you didn’t have one little thing to do with it, right?” She sank down on the bed, moaning, her head rolling back and forth. “I can just see your dad looking at me. That look of his, oh boy. Like don’t I have any brains? Like why wasn’t I on the pill?”

“We’ll tell them as soon as we get back. It’ll take them a day or two, that’s all. Then they’ll get used to it.”

She turned and gave him a shrewd look. “What about you? When are you going to get used to it?”

“I am used to it.”

“Oh yeah, sure. I’m like sitting there on the bus, day after day, thinking up names. Girls’ names. Boys’ names. That’s what’s in my head. I like Victoria for a girl. For a boy I like Troy. Those kinds of thoughts. And you’re jumping up and down looking at bushes. Writing them down. That’s all you care about. Goddamn fucking bushes.”

He pulled her close to him, rocking her back and forth, patting her hair.

Startled, he recognized that pat, its cruel economy and monumental detachment. It was the sign of someone who was distracted, weary. A husband’s pat. He’d seen his father touch his mother in exactly the same way when she fell into one of her blue days. Only patting wasn’t really the same thing as touching. Patting a person was like going on automatic pilot, you just reached out and did it. There, there. Looking covertly at his watch. Almost dinnertime. Pat, stroke, pat.

It calmed her. She collapsed against him. They lay back on the bed, hanging on to each other limply and not saying anything. In ten minutes it would be time to go down to the dining room. He was ravenous.

A single day remained – and one more major historical site to take in: Hampton Court.

“This palace is unrivaled,” Arthur said, gathering his charges in a tight circle around him, “for its high state of preservation.” He pointed out Anne Boleyn’s Gateway, the Astronomical Clock (electrified two years ago), the Great Hall, the Fountain Court, the Chapel Royal with its intricately carved roof. “Note the quality of the workmanship,” he said. “What you behold is a monument to the finest artists and artisans in the land.”

The members of the tour group had taken up a collection, and the evening before they’d presented Arthur with a set of silver cufflinks. He had blinked when he opened the jeweler’s box, blinked and looked up into their waiting faces. “For he’s a jolly good fellow,” one of the Australians sang out, trying to get a round going. The man’s name was Brian. He was large, kindly, and elegantly bald. It was he who had taken up the collection for Arthur and passed around a thank-you card for everyone to sign. But he launched the song in a faltering key that no one could follow.

Surprisingly, it was Dorrie who moved forward and picked up the melody, drawing in the others with her strong, clear voice. She came from a musical family; her father sang baritone with the Police Chorale; her mother, after a few drinks, belted out a torchy rendition of “You Light Up My Life.” And Dorrie’s voice, despite her size, a mere one hundred pounds, was true and forceful.

For he’s a jolly good fellow

Which nobody can deny.

At that moment Larry loved her terribly. His helpless Dorrie. He froze the frame in his mind. This was something he needed to remember. The upward tilt of her chin as she risked a minor feat of descant on the final words. The way her hands curled inside her raincoat pockets, plunging straight forward into a second chorus, as though she’d been anointed, for a brief second or two, Miss Harmony of Sunbrite Tours.

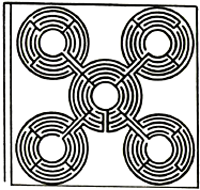

Mrs. Edwards had wondered aloud about the appropriateness of cufflinks for Arthur. “He doesn’t look like a man who is particularly intimate with French cuffs,” she whispered to her husband and to Larry and Dorrie. But this morning, following Arthur into Hampton Court gardens, Larry glimpsed a flash of silver at Arthur’s wrist. “Before you,” Arthur said, pointing, “is the oldest surviving hedge maze in England.”

A what? Larry had never heard of a hedge maze.

“We’ve got three-quarters of an hour,” Arthur announced in his jolly voice. “If you get lost, just give us a shout and we’ll come and rescue you.”

Later, Larry memorized the formula for getting through the maze. He could recite it easily for anyone who cared to listen. Turn left as you enter the maze, then right, right again, then left, left, left and yet another left. That brings you to the centre. To get out, you unwind, turning right, then three more rights, then a left at the next two turnings, and you’re home free.

But on the day he first visited the Hampton Court maze, March 24, 1978, a young, untraveled floral designer from the middle of Canada, the newly married husband of Dorrie Shaw who was four months pregnant with his son Ryan – on that day he took every wrong turning. He was, in fact, the last of the tour group to come stumbling out of the maze’s exit.

Dorrie in her perky blue raincoat was standing, waiting. “We were worried,” she said to him crossly. Then, “You look dizzy.”

It was true. The interior of the maze had made him dizzy. It was very early in the morning, a frosty day, so cold he could see his breath as it left his mouth and widened out in the air. It seemed a wonder that the tender needlelike leaves could withstand such cold. The green walls rose about him, too high to see over. Who would have expected such height and density? And he hadn’t anticipated the sensation of feeling unplugged from the world or the heightened state of panicked awareness that was, nevertheless, repairable. Without thinking, he had slowed his pace, falling behind the others, willing himself to be lost, to be alone. He could see Mrs. Edwards ahead of him on the narrow path, walking side by side with Dorrie, their heads together, talking, and Mr. Edwards following close behind. Larry watched the three of them take a right-hand turn and disappear behind a bank of foliage.

He wondered exactly how lost a person could get. Lost at sea, lost in the woods. Fatally lost.

“You look lost in thought,” Vivian had said to him on his last day at Flowerfolks, the day before he and Dorrie were married. He had been in the back of the store, staring into a blaze of dyed blue carnations. “I was just thinking,” he told her, and she had floated him a lazy smile. “Communing with the merchandise?” she said, touching the sleeve of his jacket. “I do it all the time.”

He had been reflecting, while staring at the fringed blue petals, about love, about the long steady way his imperfect parents managed to love each other, and about his own deficient love for Dorrie, how it came and went, how he kept finding it and losing it again.

And now, here in this garden maze, getting lost, and then found, seemed the whole point, that and the moment of willed abandonment, the unexpected rapture of being blindly led.

In the distance he could hear a larky Australian accented voice – one of their own group – calling “This way, this way.” He shrank from the sound, its pulsating jollity, wanting to push deeper and deeper into the thicket and surrender himself to the maze’s cunning, this closed, expansive contrivance. He observed how his feet chose each wrong turning, working against his navigational instincts, circling and repeating, and bringing on a feverish detachment. Someone older than himself paced inside his body, someone stronger too, cut loose from the common bonds of sex, of responsibility. Looking back he would remember a brief moment when time felt mute and motionless. This hour of solitary wandering seemed a gift, and part of the gift was an old greedy grammar flapping in his ears: lost, more lost, utterly lost. He felt the fourteen days of his marriage collapsing backward and becoming an invented artifact, a curved space he must learn to fit into. Love was not protected. No, it wasn’t. It sat out in the open like anything else.

Forty-five minutes, Arthur had given them. But Larry Weller had lingered inside the green walls for a full hour.

“We were worried,” Dorrie said. Scolding.

He followed her into the coach for the ride back to London. “How could you get yourself so lost?” she kept asking. The next day they boarded a plane that carried them across a wide ocean, then over the immense empty stretches of Labrador and the sunlit cities and villages of Ontario, an endless afternoon of flight. Frozen lakes and woodlands spread beneath them, thinning finally, flattening out to a corridor of snow-covered fields and then the dark knowable labyrinth of tangled roadways and rooftops and clouds of cold air rising up to greet them.

A sweet soprano bell dinged for attention. Seat belts buckled, tables up, the landing gear grinding down, a small suite of engineering miracles carefully sequenced. Dorrie gave Larry’s hand an excited, distracted squeeze that said: almost home. They were about to be matter-of-factly claimed by familiar streets and houses and the life they’d chosen or which had chosen them.

Departures and arrivals: he didn’t know it then, but these two forces would form the twin bolts of his existence – as would the brief moments of clarity that rose up in between, offering stillness. A suspension of breath. His life held in his own hands.

CHAPTER THREE Larry’s Folks 1980

Shortly before Larry’s thirtieth birthday he managed to get enough money together for a down payment on a small house over on Lipton Street, a handyman special, just five rooms and a glassed-in front porch, and now he spends most evenings and weekends working on it. He and his wife, Dorrie, moved in two months ago, and ever since then she’s been after him to lay new tiles in the kitchen, and after that there’s the bathroom fixtures to replace, and maybe some ceiling insulation before winter comes along. A list as long as your arm. But this summer Larry’s been using every spare minute to work on the yard, sometimes with the help of his friend Bill Herschel, but more often alone. Might as well do it while the weather’s still good, Larry says. And he wants the whole yard closed in so Ryan can play out there next spring, unsupervised.

He’d be working at it today, only his folks have invited him and Dorrie and the baby over for the birthday festivities. Sunday dinner, opening his presents from the family, blowing out the candles, the usual. It’s 1980; he’s about to enter the decade of decadence, only he doesn’t know that yet, no one does; he only knows he feels the good hum of almost continuous anticipation in his chest, even though Dorrie griped all the way over to his folks’ place about how they were probably going to have a hot dinner, gravy and everything, when here it was, the bitch end of a sizzling day. Her own idea of hot weather fare is a big bowl of ice-cream and a glass of iced tea.

A brutal bored silence had fallen between them these last weeks.

A mere three years ago he was a young buck walking down a Winnipeg street in his shirt-sleeves. He remembers how that felt, no wife, no kid, no house, no yard. Now the whole picture’s changed, but that’s okay, especially his kid, Ryan. Another thing: he’s supposed to be sunk in gloom at the thought of turning thirty, but he isn’t. He’s unique and mortal, he knows that, and he’s got this sweet little babe of a house, and a yard that’s slowly taking shape, all its corners filling up with transplanted shrubs from the wholesaler down in Carmen. There’re some flowers too, and a few sweet peppers, but it’s mainly the shrubs he loves. Dorrie keeps calling them bushes, and he keeps having to correct her. “You’ve got shrub mania,” she says, but her lips smile when she’s saying it. “You want to be the shrub king of the universe.”

Maybe it’s true. Maybe he wants to make his yard a real shrub showplace. Somewhere Larry’s heard that almost everyone in the world is allowed one minute of fame in their lives, or maybe that’s one hour.

Stu Weller, Larry’s dad, got written up once in the weekend section of the Winnipeg Tribune on the subject of his corkscrew and bottle-opener collection, which included 600 items at the time of the interview, and has almost doubled since. Larry’s older sister, Midge, won a thousand dollars last year in the art gallery raffle – enough for a trip to Hawaii with a girlfriend – and she actually appeared on Channel 13 talking about how surprised she was, and how she didn’t usually waste money on raffle tickets unless it was for a good cause like expanding the gallery’s exhibition space or something.

Larry’s own moment of fame is still some years in the future, and that’s fine with him. He’s got enough on his mind these days, his young family – Dorrie, little Ryan – and his job at Flowerfolks, and his current preoccupation with transforming his yard. As for his mother, Dot, she’s had enough celebrity for a lifetime. Don’t even talk to her about being famous, especially not the kind of fame that comes boiling out of ignorance, and haunts you for the rest of your life. Dumb Dot. Careless Dot. Dot the murderer. Of course, that was a long time ago.

When Larry was a little kid his mother warned him about the dangers of public drinking fountains. “No one ever, ever puts their mouth right on the spout,” she said, “because they can pick up other people’s germs, and who knows what kind of disease you’ll get.”

This was bad news for Larry. At that age he liked to stand on tiptoe and press his lips directly on the cool silvery water spout, rather than trying to catch the spray in his mouth as it looped unpredictably upward. Besides, his mother’s caution didn’t make sense, since if no one ever touched the spout, how could there be any germs? He recalls – he must have been six or seven at the time – that he presented this piece of logic to his mother, but she only shook her headful of squashed curls and said sadly, wisely, “There will always be people in this world who don’t know any better.”

He pictured these people – the people who didn’t know any better – as a race of clumsy unfortunates, and according to his mother there were plenty of them living right here on Ella Street in Winnipeg’s West End: those people who mowed their lawns but failed to rake up the clippings, for instance. People who didn’t know any better stored cake flour and other staples in their original paper bags so that their cupboards swarmed with ants and beetles. They never got around to replacing the crumbling rubber-backed placemats from the Lake of the Woods with “The Story of Wood Pulp” stamped in the middle. That was the problem with people who didn’t know any better: they never threw things away, not even their stained tea-towels, not even their oven mitts with holes burnt right through the fingers.

People who didn’t know any better actually ate the coleslaw that came with their hamburgers, poking it out of those miniature pleated paper cups with their stabbing forks. Someone, their well-meaning mothers probably, told them they should eat any and all green vegetables that were put in front of them, not that there’s anything very green about coleslaw, especially when it’s been sitting in a puddle of wet salad dressing and improperly refrigerated for heaven only knows how many days. These people have never heard of the word salmonella, or if they have, they probably can’t pronounce it.

Whereas Dot (Dorothy) Woolsey Weller, wife of Stu Weller, mother of Larry and Midge, grandmother of Ryan, knows about food poisoning intimately, tragically. She was, early in her life, an ignorant and careless person, one of those very people who didn’t know any better and who will never be allowed, now, to forget her lack of knowledge. She’s obliged to remember every day, either for a fleeting moment – her good days – or for long suffering afternoons of gloom. “Your mother’s got a nip of the blues today,” Stu Weller used to tell his kids while they were growing up in the Ella Street house, and they knew what that meant. There sat their mother at the kitchen table, again, still in her chenille robe, again, when they got home from school, her hands rubbing back and forth across her face, and her eyes blank and glassy, reliving her single terrifying act of infamy.

Even today, August 17th, her son’s thirtieth birthday, she’s remembering. Larry knows the signs. It’s five-thirty on a Sunday afternoon, and there she is, high-rumped and perspiring in her creased cotton sundress, busying herself in the kitchen, setting the dinner plates on top of the stove to warm, as if they weren’t already hot from being in a hot kitchen. She’s peering into the oven at the bubbling casserole, and she’s floating back and forth, fridge to counter, counter to sink. Her large airy gestures seem to have sprung not from her life as wife and mother, but from a sunny, creamy, abundant girlhood, which Larry doubts she ever had. She smiles and she chats and she even flirts a little with her thirty-year-old son, who looks on, a bottle of cold beer in his hand, but he knows the old warnings. Her jittery detachment gives her away. She picks up a jar of pickles and bangs it hard on the breadboard to loosen the lid. She’s thinking and fretting and knowing and feeling sick with the poison of memory.