Полная версия

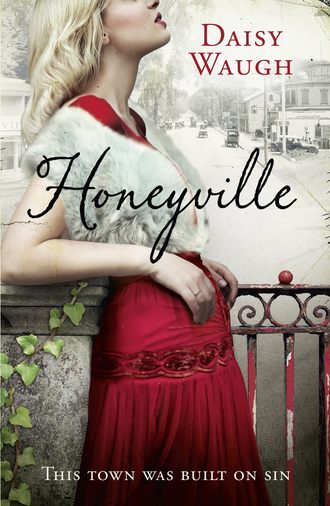

Honeyville

I recognized all three men. Two were private detectives, from the notorious Baldwin-Felts detective agency, hired by the coal company to report on revolutionary activity among the workers. They and their like had been throwing their weight around Trinidad these past few months. They roamed the streets with handguns tucked under their shirts, picking fights when and wherever the fancy took them. Nobody seemed to stop them – except Phoebe, my boss and the proprietress of Plum Street. Phoebe didn’t ban many men from our parlour house, so long as they could stand the bill. So it was a measure of how brutish they were that she had banned entrance to all the Baldwin-Felts men. They had a reputation for violence, here and across Colorado – all over America in fact. Wherever employers hired them to harass and intimidate their workers.

The third man wasn’t much better. Another out-of-towner, come to Trinidad to make mischief. It was Captain Lippiatt, employed by the other side. He was a Union man. And I knew him, because he had visited us at the parlour house.

The three men stood chest to chest, eyeball to eyeball, in the middle of North Commercial, the spit flying in each other’s faces: three great bulls of male-hood, of pure and dangerous absurdity, it seemed to me. I had no wish to be anywhere near them. I slipped deeper into the store.

Inez, on the other hand, seemed unaware of the danger. She looked up from her skin-freshening packaging, and exclaimed, ‘Oh my!’ at such a volume that one of the spitting men – it was Lippiatt – paused momentarily to glance in.

‘Mr Carravalho, what are they doing?’ she asked, ‘What on earth do you suppose they’re arguing about?’

‘Union men,’ he muttered, shrinking a little behind his high wooden counter. ‘Hush up now, Miss Dubois. We don’t want them coming in here.’

‘All three are Union men?’ she asked, staring brazenly and without dropping her voice. ‘Then why are they fighting? You might have thought, after all the trouble they cause, they would at least have the decency to agree with one another.’

‘There’s a bunch of them in town this week,’ he replied. ‘Causing trouble. Some kind of delegation at the theatre. Talking about a strike—’

‘But they’re not all Union men,’ I interrupted. I wasn’t supposed to speak to the likes of Miss Inez Dubois. And nor she to the likes of me, except in a soul-saving, charitable capacity. Mr Carravalho looked shocked and embarrassed. They both did. But I persevered. It wasn’t that I had any special loyalty to the Union men (far from it), but it struck me as just plain ignorant to pretend that the battle on our streets was being fought by only one army. ‘One of them is, but the other two on the right are Baldwin-Felts men. You know that, Mr Carravalho. They’re coal company heavies. And it’s no good taking sides. Those men are as bad as each other.’

The fight, meanwhile, seemed to have disbanded. Lippiatt was gone. Even so, the two Baldwin-Felts detectives lingered. They crossed over to the far side of the street, looking cautiously about them, dust whipping round their boots. The Friday night crowd gave them plenty of space.

‘What are they doing?’ Inez asked.

It was hard to tell. They were leaning side by side of each other against a power post directly opposite us, hands resting on guns that poked ostentatiously from under their shirts. They gazed up the street towards the Union offices a few doors down, but nothing happened.

‘Well!’ Inez sighed. ‘Thank goodness for that! Is it over? I should be heading back.’

‘I’m sure you’re right, Miss Dubois,’ Mr Carravalho said. ‘It’s rather late for a lady to be trekking the streets. And on an evening like this. With the Union coming into town.’ He shot me a glance. ‘You hurry on home. Will you be taking that?’ he indicated the package still in her hand.

She looked down, remembering it. ‘Why yes!’ she cried, as if it was quite the boldest and happiest decision she had ever settled upon. ‘Sure, I’ll take it! Why not?’ And while Mr Carravalho wrapped it, she looked again, past me – through me, I suppose – to the street outside, where the two detectives had still not moved on.

‘They really ought to get going,’ she muttered, sounding nervous at last. She squinted a little closer, noticed the hands and guns. ‘Aunt Philippa says they are quite trigger-happy, these Union men. Do you think it’s safe to walk home?’

‘Pardon me,’ I said again, ‘but those aren’t Union men.’

She wasn’t listening. ‘It’s getting so rowdy, our little town,’ she muttered; I’m not certain which of us she was addressing. ‘I really don’t know why we have to put up with it. I begin to think – Oh! Oh Mr Carravalho! Oh my gosh—’

Captain Lippiatt had returned. He must have dashed directly into the Union office, snatched up the gun and turned straight back again. It explained, perhaps, why the Baldwin-Felts brutes had lingered. Perhaps they had known he was coming back.

Lippiatt charged towards them through the scattering crowd. ‘See now,’he shouted, ‘see now, cock chafers, see if you’ll repeat what you just said to me!’ He shook his gun at them. ‘Do you dare say it now, sons of bitches?’

In an instant the street emptied. On the corner of Elm Street, the choir stopped its singing and melted into the retreating crowd. But we were trapped. Directly before us, the detectives snatched up their own guns. Lippiatt was already beside them, his handgun poking at them. There was a confusing scramble of limbs, and more cursing, and then a shot. One of the detectives had been hit in the thigh.

Inez screamed. I put a hand on her shoulder to quiet her and she buckled beneath my touch. I let her fall.

This was not the first shooting I’d seen on the streets of Trinidad, nor would it be the last. But it was the closest I had ever been: so close I could swear I heard the soft thump of bullet as it hit his flesh. Afterwards some of the blood got onto my silk shoes, and no matter how well I scrubbed them, it would never shift.

There came another shot, this one from the handgun of the other detective. Lippiatt staggered back. Another shot, and he fell to the ground. And this I can never forget – the first detective stumbled forward and aimed his gun at Lippiatt as he lay helpless at his feet, and he shot him through the neck. Tore a hole through Lippiatt’s neck with the bullet. And then he shot him again, through the chest. That’s when the blood began to flow.

A couple of Union men appeared within moments, while we stood still, looking on, frozen with fear. They carried his body back into their Union lair, a thick trail of blood following them along the way. Lippiatt was dead. And I knew his name because last time he’d been in town, he paid me a visit at the Plum Street Parlour House. He was an Englishman. Or he had been English, once. Just as I had. It was the only reason I recalled him at all. Perhaps the only reason he chose me before the other girls. We didn’t talk about our Englishness in any case. Nor about anything else, come to that. Very taciturn, he was. Unsmiling. Smelled of the tanner – and my disinfectant soap. But they all smell of that. And he left without saying thank you. I can’t say I was sorry he was dead. But even so, it was a shock, to have been standing right there and seen it happen … and to remember (dimly) the feel of the man between my legs. And then there was Inez, collapsed on the floor at my feet. Poor darling.

I was shaken up. We all were. But Inez seemed to take the drama personally, as if it was her own mother who’d been slain before her eyes. She sat on the floor, her long blue skirt in a sober pool around her, and her little hat lopsided. She wouldn’t stand, no matter how Mr Carravalho and I, and finally Mrs Carravalho, tried to coax her. She simply sat and swayed, face as white as a ghost.

‘That poor man,’ she kept saying, with the tears rolling down her cheeks. ‘That poor, poor gentleman! One minute he was alive, right there beside me – he looked at me! Didn’t you see? Only a second before he looked at me … And now he is absolutely dead!’

3

Perhaps, while Inez is down there on the drugstore tiles, grieving the death of my old client, I should pause to explain something about our small town of Trinidad.

Forty years earlier it had been nothing: just a couple of shacks on the open prairie; a pit stop for settlers on the Santa Fe trail. Then came the ranchers and the cowboys, and then the prospectors. Elsewhere, they found iron and oil, silver and gold. Here, in Southern Colorado, buried deep in the rocks under that endless prairie, they found coal. It was the ranchers who settled in Trinidad. It was the coal men who made it rich. And in August 1913, our little town stood proud, a great, bustling place in the vast, flat, open prairie land. Trinidad boasted a beautiful new theatre, seating several thousand; an opera house as grand as its name suggests, a score of different churches and a splendid synagogue; there were numerous schools, two impressive department stores, a large stone library, and a tram that ran to the city from the company-owned mining settlements, or ‘company towns’ in the hills. There were hotels and saloons and dancing halls, and pawn shops and drugstores and stores selling knick-knacks of every kind, and a large brick factory, and a brewing factory and – because of all that – but mostly because of the coal, there were people in Trinidad from just about every country in the world.

In 1913, Trinidad was the only town in Colorado that tolerated my trade. Consequently, there existed on the west side of Trinidad – from that handsome new theatre, and on and out – a district a quarter the size of the entire town which was dedicated to gentlemen’s pleasure: saloons (uncountable) and – according to the city censor – at least fifteen established brothels. Which number, by the way, was the tip of the iceberg. It didn’t take into account the vast quantity of independent girls – the ‘crib’ girls, who operated from small single rooms, and who worked and lived together in shifts; nor the dance-hall girls, nor the pathetic ‘sign-posters’, who worked not in rooms but wherever they could: in dark corners, shoved up against walls behind the saloons.

For most of us (not perhaps the sign-posters) Trinidad was a good place to be a whore, and a good place to find one. Snatchville, they used to call it. Ha. And the punters came from far and wide. Prostitution wasn’t simply legal in ol’ Snatchville, it was an integral part of the city. There was a Madams’ Association – a hookers’ mutual society, if you like – so rich and influential it funded an extension of the trolley line into our red-light district, and the building of a trolley bridge. ‘The Madams’ Bridge’, folk called it: built by the whores, for the whores, although really the whole town benefited. It meant the men travelling down from the camps could be transported directly into our district, without getting lost along the way, or disturbing the peace of the better neighbourhoods. The Madams’ Association provided medical care and protection to the girls, too, so long as they were attached to a brothel. And a recuperation house, not a mile out of the city, where we could retire for a week or so, if we needed a break.

Trinidad was wealthy: cosmopolitan in its own provincial fashion, conservative and yet radical. It was new, and crazy, and busting with life. But for all that, it was only a small town.

From its centre, where North Commercial crossed Main (only a few yards from where Lippiatt was shot), the entire city was never more than a ten-minute walk away: the library, where Inez worked, the jail, the city newspaper, the City Hall. Everything was clustered around the same twenty or so blocks. From the red-light district in the west, with its saloons and dancehalls, to the ladies’ luncheon clubs, church halls, and elegant tearooms in the east, the distance was hardly more than a few miles.

The ladies of Trinidad spent their dollars in the same stores. We attended the same movie theatres. We washed the same prairie dust from our hands and clothes. And yet, it was as if we lived in quite separate realities; as if we couldn’t see one another. Only the men travelled freely between our two worlds.

Inez and I, living side by side in a small, dusty town in the middle of the Colorado prairie might, our entire lives, have brushed past one another on the sidewalk, at the grocery store, the drugstore, the library, the doctor’s waiting room, at our famous department store – and never once exchanged a glance or a word. Inez and I were as shocked as each other by the evening that followed Lippiatt’s death.

… I suppose, at this point I should also explain something about myself, too? I don’t much want to, and that’s the truth. But how in the world (the question begs) did an educated English woman, thirty-seven years old and the daughter of two Christian missionaries, find herself divorced, childless and working in an upmarket Colorado brothel? How indeed.

Well, because we all find ourselves somewhere, I guess.

It’s all anyone needs to know. There, but for the grace of God … This isn’t a story about me, in any case. It’s a story about Inez and Trinidad, and the war that came to Snatchville and tore us all apart.

So there Inez sat, or slumped, on the drugstore tiles. And there were Mr and Mrs Carravalho hovering around her, polite but, I sensed, with a hint of impatience. Outside, there was panic in the voices now, and anger too. The Carravalhos wanted to close up and get home as quickly as possible. But Inez, wrapped in her own horror, was oblivious to their concerns. I might have gone on my way, come back to the shop another day. I had plenty else to do, and I was meant to be working that evening. But Lippiatt’s blood was still slick on the street outside, and I didn’t much relish the idea of venturing into the angry crowd myself. Not yet.

Mrs Carravalho disappeared into the back of the shop and returned with brandy. A single serving, for Inez – until her husband sent her back for the bottle and three more glasses. I took mine, swallowed it down and felt better at once. Inez took only the daintiest of sips, and continued to whimper.

I told her she’d feel stronger if she drank the thing down in one. She looked at me directly, I think for the first time, and immediately did as I suggested. The alcohol hit the back of her throat and she shuddered. The three of us looked on, intrigued, as the brandy continued its internal journey, until at length she looked up at the three of us, considered us one by one, and grinned.

‘Thank you all so much. I think, perhaps …’ She belched, and I laughed. Couldn’t help it. She glanced at me again, uncertain whether she dared to laugh too, and decided against it. ‘I think I should probably head home.’

‘Excellent idea,’ Mr Carravalho said.

His wife looked at her doubtfully. ‘It’s set to turn pretty mean out there. You want my husband to escort you?’

‘No, no!’ Inez said, though she plainly did.

‘Well if you are certain,’ he answered quickly.

I took her empty brandy glass and placed it with my own on the counter. I said, ‘We can leave together if you like. Just until we’re through the craziness. It’ll be much quieter on the other side of Main Street.’

There was an embarrassed pause.

‘Well I’m sure I don’t think … Honey?’ muttered the wife, looking at me suspiciously. But Mr Carravalho was apparently too busy to notice. ‘I really don’t think,’ she muttered again.

‘What’s that dear?’ He was locking up, counting notes. Protecting the business.

Inez ignored them and turned to me. ‘Which way are you headed?’ she asked boldly, and immediately blushed. ‘That is to say, I am headed east. Perhaps. I mean, for certain, I am heading east. And I don’t know – if maybe we are headed in different directions?’

‘I dare say we are,’ I said. ‘But we can walk on up to Second or Third Street together. It’s sure to be quieter up there.’

Inez glanced through the window. The sheriff had arrived and an angry gaggle had mustered round his motor, making it impossible for him to get out. It looked menacing.

‘Well,’ she said at last, ‘if it’s all the same to you, I think that would be just daisy. Thank you.’ As she stood up, she seemed to totter a little. Carefully, eyes closed in concen- tration, she straightened herself. ‘Shall we get going?’

‘You know I really don’t think …’ Mrs Carravalho murmured yet again, sending baleful looks at her husband.

‘Well, unless you want me to leave you here alone,’ her husband snapped at last, ‘with all the trouble brewing and the store unguarded, and the week’s takings still in the register, and you, no use with a handgun …’

‘Well but even so,’ she was saying.

We left them squabbling and stepped out into the teeming street, Lippiatt’s blood still damp between the bricks at our feet.

We had hardly walked a half-block before she stopped, grasped hold of my shoulder.

‘Hey, what do you say we sit down?’ she said. Her face was whiter than ever.

‘You want something more to drink?’ Truth be told, I didn’t feel so hot myself.

She nodded.

We might have stopped at the Columbia Hotel, just across the street. Or at the Horseshoe Club, ten doors down. Or at the Star Saloon at the corner. There was no shortage of choice. But we stopped at the Toltec. At the moment she grasped hold of me, and I was convinced she might faint right away, it happened we were right bang beside its entrance. So we turned in, and plumped ourselves at a table at the end of the room, as far from the hubbub as possible.

The Toltec was plush and newly opened then; a saloon attached to a swanky hotel, both of which, I knew, were popular with visiting Union men. It was a saloon much like any other, maybe a little more comfortable. There was a high mahogany bar running the length of the room, an ornate, pressed-tin roof, still shiny with newness, and a lot of standing room. We sat beneath that shiny ceiling and ordered whiskey. A bottle of it. And for a while the bar was quiet.

‘Everyone’s out on the streets,’ the barman told us as we settled ourselves at the table.

‘Making trouble,’ Inez said.

‘Depends on your way of looking at things,’ muttered the barman.

We filled our glasses and turned away from him. ‘But you know everyone I know agrees,’ she told me, sucking back on her whiskey. (She may not have been accustomed to liquor, but I noticed she had taken a liking to it fast enough.) ‘These anarchists come into town with their crazy ideas, and then they infiltrate the camps and stir up the miners. The men were perfectly happy before the Unions came in. And now look where we are! Death on every doorstep! Murder at the drugstore!’

‘To Captain Lippiatt,’ I said, to shut her up. I didn’t want to talk politics – not with anyone, and least of all with her. ‘May he rest in peace.’

She stared at me, whiskey glass halted. ‘Captain Who?’ and then, ‘You know his name? You mean to say you knew him?’

‘Hardly very well. But yes, I guess knew him.’

‘How?’ And then, in a rush of embarrassment, and without giving me a chance to answer: ‘Oh gosh but never mind that!Did I tell you already – I work at the library. Do you ever go in there? You should. I’ll bet there are plenty books I could show you that you might enjoy.’

‘I love to read,’ I told her. ‘And I am often in the library. I’ve seen you in there before.’

‘It’s quite a thrill you know,’ she skipped on (I imagine the library was the very last thing she wanted to talk about). ‘I mean, once you get over the shock of it, and all. It’s quite a thrill to be here in this saloon. I’ve been walking past saloons all my life, never even daring to peep in. And now here I am,’ she beamed at me, ‘in a saloon! With you! It feels like the greatest adventure.’

‘I suppose it is,’ I said. ‘For you and me both.’

‘Do you suppose your friend Mr Lippiatt—’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t say he was a friend.’

‘No. But do you suppose he had a wife? Or children? Or anything like that? Maybe a mama. I think I should go visit them. Don’t you think I should?’

I laughed. ‘Whatever for?’

‘Whatever for? He and I, we looked at each other. Don’t you see the significance?’

‘Not really.’

‘Well, mine was probably the last human face, the last decent human face, not in the process of slaughtering him, which that poor gentleman ever laid eyes on. And then – Pop! He was dead.’ She sniffed. Picked up her glass. Glanced at me. ‘Y’know this is silly. Here we are, you and me, drinking in a saloooon together.’ She rolled the word joyfully around her mouth. ‘And I don’t even know your name. I am Inez Dubois, by the way.’

‘How do you do.’

‘I live with my aunt and uncle. Mr McCulloch. You’ve probably heard of him? Have you?’

‘No,’ I said automatically. Whether I had heard of him or not.

‘Mr McCulloch is my uncle.’

‘So you said.’

‘Well, he’s one of the old families. Ranching. Cattle. That’s where his money comes from. So he’s got no business with the coalmines, thank blame for that …’ She glanced at me. Already, her eyes were growing fuzzy with liquor. ‘Don’t you think so?’

‘It’s all the same to me.’

‘Even if the miners do get a fair wage. And nice homes and little yards and free schools and everything they could possibly ask for. Well, it’s all stirred up by the Unions now, isn’t it? And I would hate that. Just wouldn’t feel right, you know? To live off other people’s discontent. Whereas the ranchers aren’t like that. They’re altogether …’ She frowned. ‘Well, anyway, they’re not the same.’

Inez Dubois looked and behaved much younger than her age. She was twenty-nine years old, she told me that night (making her eight years my junior), the orphaned child of Mrs McCulloch’s sister, who died alongside Inez’s father in what Inez described as, ‘one of these train-track accidents’. She didn’t go into details, and I didn’t ask for them. Her parents died back in 1893, in Austin, Texas, and after the funeral Inez and her older brother Xavier were sent to Trinidad to live with their only living relation. The McCullochs had no children, and though Richard McCulloch was aloof and uninterested, his wife treated her nephew and niece as her own. Inez never moved out. Her brother Xavier, on the other hand, had left town some ten years previous, at the age of twenty-five, and though he wrote to Inez once a week, often enclosing a variety of books and magazines he believed might educate or amuse her, he’d not returned to Colorado since.

‘He’s in Hollywood now. Silly boy,’ Inez said, though by my calculation, he was a good six years her senior. ‘He’s making movies,’ she said. ‘Though I’ve never actually seen any, so I don’t suppose he really is. He says I would love it in Hollywood. It’s summertime – only cooler – a cooler summer, all year long. Sounds heavenly doesn’t it? Shall we go there together?’ She giggled. ‘After what happened today, I tell you I’m just about ready to leave this place. I wasn’t far off ready before. And now … Truthfully. I’m sick to death of it. Are you?’

‘Kind of …’ I laughed. It must have sounded more mournful than I intended.

She looked at me with her big, earnest eyes. She said, ‘You do realize, don’t you, that there are about a million questions I want to ask you. About everything. Only I guess I have a pretty good idea what it is you do.’She looked so uncomfortable I thought she might burst into tears again. I had to bite my lip not to smile. ‘And I don’t mean to pry. It’s probably why I’m yakking on like this. It just makes me nervous, that’s all. Because here we are, sitting here, and we’ve been through this terrible, awful thing together, when normally we wouldn’t even speak. And I was impolite to you in the drugstore, but you know I didn’t mean to be. I guess I just didn’t know any better. Because we can’t live more than a handful of miles apart and yet …’ She took a breath. ‘I don’t quite even know where to begin.’