Полная версия

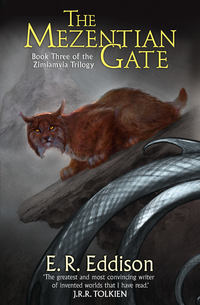

A Fish Dinner in Memison

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © E. R. Eddison 1941

Jacket illustration by John Howe © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2014

E.R. Eddison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578153

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007578160

Version: 2014-09-09

Dedication

To my son-in-law

Flying Officer KENNETH HESKETH HIGSON

who in an air fight over Italy

saved his four companions’ lives

at cost of his own

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK

which he had twice read.

Proper names the reader will no doubt pronounce as he chooses. But perhaps, to please me, he will let Memison echo ‘denizen’ except for the m: pronounce the first syllable of Reisma ‘rays’: keep the i’s short in Zimiamvia and accent the third syllable: accent the second syllable in Zayana, give it a broad a (as in ‘Guiana’), and pronouce the ay in the first syllable (and also the ai in Laimak, Kaima, etc., and the ay in Krestenaya) like the ai in ‘aisle’: accent the first syllable in Rerek and make it rhyme with ‘year’: keep the g soft in Fingiswold: remember that Fiorinda is an Italian name, Beroald (and, for this particular case, Amalie) French, and Zenianthe, and several others, Greek: last, regard the sz in Meszria as ornamental, and not be deterred from pronouncing it as plain ‘Mezria’.

This divine beauty is evident, fugitive, impalpable, and homeless in a world of material fact; yet it is unmistakably individual and sufficient unto itself, and although perhaps soon eclipsed is never really extinguished: for it visits time and belongs to eternity.

GEORGE SANTAYANA

EURIPIDES, ION, 1615

… though what if Earth

Be but the shaddow of Heav’n, and therein

Each to other like, more than on earth is thought?

MILTON, PARADISE LOST, V. 571

Ces serments, ces parfums, ces baisers infinis,

Renaîtront-ils d’un gouffre interdit à nos sondes,

Comme montent au ciel les soleils rajeunis

Après s’être lavés au fond des mers profondes?

—O serments! ô parfums! ô baisers infinis!

BAUDELAIRE, LE BALCON

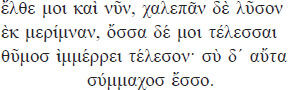

SAPPHO, ODE TO APHRODITE

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction by James Stephens

A LETTER OF INTRODUCTION

I. Aphrodite in Verona

II. Memison: King Mezentius

III. A Match and Some Lookers on

IV. Lady Mary Scarnside

V. Queen of Hearts and Queen of Spades

VI. Castanets Betwixt the Worlds

VII. Seven Against the King

VIII. Lady Mary Lessingham

IX. Ninfea di Nerezza

X. The Lieutenant of Reisma

XI. Night-Piece: Appassionato

XII. Salute to Morning

XIII. Short Circuit

XIV. The Fish Dinner: Praeludium

XV. The Fish Dinner: Symposium

XVI. The Fish Dinner: Caviar

XVII. In What a Shadow

XVIII. Deep Pit of Darkness

XIX. Ten Years: Ten Million Years: Ten Minutes

NOTE

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

MAP OF THE THREE KINGDOMS

ALSO BY E. R. EDDISON

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

BY JAMES STEPHENS

THIS is a terrific book.

It is not much use asking, whether a given writer is great or not. The future will decide as to that, and will take only proper account of our considerations on the matter. But we may enquire as to whether the given writer does or does not differ from other writers: from, that is, those that went before, and, in especial, from those who are his and our contemporaries.

In some sense Mr Eddison can be thought of as the most difficult writer of our day, for behind and beyond all that which we cannot avoid or refuse – the switching as from a past to something that may be a future – he is writing with a mind fixed upon ideas which we may call ancient but which are, in effect, eternal: aristocracy, courage, and a ‘hell of a cheek’. It must seem lunatic to say of any man that always, as a guide of his inspiration, is an idea of the Infinite. Even so, when the proper question is asked, wherein does Mr Eddison differ from his fellows? that is one answer which may be advanced. Here he does differ, and that so greatly that he may seem as a pretty lonely writer.

There is a something, exceedingly rare in English fiction, although everywhere to be found in English poetry – this may be called the aristocratic attitude and accent. The aristocrat can be as brutal as ever gangster was, but, and in whatever brutality, he preserves a bearing, a grace, a charm, which our fiction in general does not care, or dare, to attempt.

Good breeding and devastating brutality have never been strangers to each other. You may get in the pages of, say, The Mahabharata – the most aristocratic work of all literature – more sheer brutality than all our gangster fictionists put together could dream of. So, in these pages, there are villanies and violences and slaughterings that are, to one reader, simply devilish. But they are devilish with an accent – as Milton’s devil is; for it is instantly observable in him, the most English personage of our record and the finest of our ‘gentlemen’, that he was educated at Cambridge. So the colossal gentlemen of Mr Eddison have, perhaps, the Oxford accent. They are certainly not accented as of Balham or Hoboken.

All Mr Eddison’s personages are of a ‘breeding’ which, be it hellish or heavenish, never lets its fathers down, and never lets its underlings up. So, again, he is a different writer, and difficult.

There is yet a distinction, as between him and the rest of us. He is, although strictly within the terms of his art, a philosopher. The ten or so pages of his letter (to that good poet, George Rostrevor Hamilton) which introduces this book form a rapid conspectus of philosophy. (They should be read after the book is read, whereupon the book should be read again.)

It is, however, another aspect of being that now claims the main of his attention, and is the true and strange subject of this book, as it is the subject of his earlier novels, Mistress of Mistresses and The Worm Ouroboros, to which this book is organically related. (The reader who likes this book should read those others.)

This subject, seen in one aspect, we call Time, in another we call it Eternity. In both of these there is a somewhat which is timeless and tireless and infinite – that something is you and me and E. R. Eddison. It delights in, and knows nothing of, and cares less about, its own seeming evolution in time, or its own actions and reactions, howsoever or wheresoever, in eternity. It just (whatever and wherever it is) wills to be, and to be powerful and beautiful and violent and in love. It enjoys birth and death, as they seem to come with insatiable appetite and with unconquerable lust for more.

The personages of this book are living at the one moment in several dimensions of time, and they will continue to do so for ever. They are in love and in hate simultaneously in these several dimensions, and will continue to be so for ever – or perhaps until they remember, as Brahma did, that they had done this thing before.

This shift of time is very oddly, very simply, handled by Mr Eddison. A lady, the astounding Fiorinda, leaves a gentleman, the even more (if possible) astounding Lessingham, after a cocktail in some Florence or Mentone. She walks down a garden path until she is precisely out of his sight: then she takes a step to the left, right out of this dimension and completely into that other which is her own – although one doubts that fifty dimensions could quite contain this lady. Whereupon that which is curious and curiously satisfying, Mr Eddison’s prose takes the same step to the left and is no more the easy English of the moment before, but is a tremendous sixteenth- or fifteenth-century English which no writer but he can handle.

His return from there and then to here and now is just as simple and as exquisitely perfect in time-phrasing as could be wished for. There is no jolt for the reader as he moves or removes from dimension to dimension, or from our present excellent speech to our memorable great prose. Mr Eddison differs from all in his ability to suit his prose to his occasion and to please the reader in his anywhere.

This writer describes men who are beautiful and powerful and violent – even his varlets are tremendous. Here, in so far as they can be conjured into modern speech, are the heroes. Their valour and lust is endless as is that of tigers: and, like these, they take life or death with a purr or a snarl, just as it is appropriate and just as they are inclined to. But it is to his ladies that the affection of Mr Eddison’s great and strange talent is given.

Women in many modern novels are not really females, accompanied or pursued by appropriate belligerent males – they are mainly excellent aunts, escorted by trustworthy uncles, and, when they marry, they don’t reproduce sons and daughters, they produce nephews and nieces.

Every woman Mr Eddison writes of is a Queen. Even the maids of these, at their servicings, are Princesses. Mr Eddison is the only modern man who likes women. The idea woman in these pages is most quaint, most lovely, most disturbing. She is delicious and aloof: delighted with all, partial to everything (ça m’amuse, she says). She is greedy and treacherous and imperturbable: the mistress of man and the empress of life: wearing merely as a dress the mouse, the lynx, the wren or the hero: she is the goddess as she pleases, or the god; and is much less afraid of the god than a miserable woman of our dreadful bungalows is afraid of a mouse. And she is all else that is high or low or even obscene, just as the fancy takes her: she falls never (in anything, nor anywhere) below the greatness that is all creator, all creation, and all delight in her own abundant variety. Je m’amuse, she says, and that seems to her, and to her lover, to be right and all right.

The vitality of the recording of all this is astonishing: and in this part of his work Mr Eddison is again doing something which no other writer has the daring or the talent for.

He is also trying to do the oddest something for our time – he is trying to write prose. ’Tis a neglected, almost a lost, art, but he is not only trying, he is actually doing it. His pages are living and vivid and noble, and are these in a sense that belongs to no other writer I know of.

His Fish Dinner is a banquet such as, long ago, Plato sat at. As to how Mr Eddison’s philosophy stands let the philosophers decide: but as to his novel, his story-telling, his heroical magnificence of prose, and his sense of the splendid, the voluptuous, the illimitable, the reader may judge of these things by himself and be at peace or at war with Mr Eddison as he pleases.

This is the largest, the most abundant, the most magnificent book of our time. Heaven send us another dozen such from Mr Eddison,

JAMES STEPHENS

15th December 1940

A LETTER OF INTRODUCTION

TO GEORGE ROSTREVOR HAMILTON

MY dear George,

You have, for both my Zimiamvian books, so played Pallas Athene – sometimes to my Achilles sometimes to my Odysseus – counselling, inciting, or restraining, and always with so foster-brotherly an eye on the object we are both in love with, that it is to you sooner than to anyone else that this letter should be addressed. To you, a poet and a philosopher: from me, who am no poet (for my form is dramatic narrative in prose), nor philosopher either. Unless to be a humble lover of wisdom earns that name, and to concern myself as a storyteller not so much with things not of this world as with those things of this world which I take to be, because pre-eminently valuable, therefore pre-eminently real.

The plain ‘daylight’ parts of my story cover the years from April 1908 to October 1933; while, as for the month that runs contemporaneously in Zimiamvia (from Midsummer’s Day, Anno Zayanae Conditae 775, when the Duke first clapped eyes on his Dark Lady, to the 25th July, when his mother, the Duchess of Memison, gave that singular supper-party), it is sufficient to reflect that the main difference between earth and heaven may lie in this: that here we are slaves of Time, but there the Gods are masters.

There are no hidden meanings: no studied symbols or allegories. It is the defect of allegory and symbolism to set up the general above the individual, the abstract above the concrete, the idea above the person. I hold the contrary: to me the value of the sunset is not that it suggests to me ideas of eternity; rather, eternity itself acquires value to me only because I have seen it (and other matters besides) in the sunset and (shall we say) in the proud pallour of Fiorinda’s brow and cheeks – even in your friend, that brutal ferocious and lionlike fox, the Vicar of Rerek – and so have foretasted its perfections.

Personality is a mystery: a mystery that darkens as we suffer our imagination to speculate upon the penetration of human personality by Divine, and vice versa. Perhaps my three pairs of lovers are, ultimately, but one pair. Perhaps you could as truly say that Lessingham, Barganax, and the King (on the one hand), Mary, the Duchess, and Fiorinda (on the other), are but two persons, each at three several stages of ‘awakeness’, as call them six separate persons.

And there are other teasing mysteries besides this of personality. For example: Who am I? Who are you? Where did we come from? Where are we going? How did we get here? What is ‘here’? Were we ever not ‘here’, and, if so, where were we? Shall we someday go elsewhere? If so, where? If not, and yet we die, what is Death? What is Time, and why? Did it have a beginning, and will it have an end? Whatever the answer to the last two questions (i.e., that time had a beginning or that it had not: or an end) is either alternative conceivable? Are not both equally inconceivable? What of Space (on which very similar riddles arise)? Further, Why are we here? What is the good of it all? What do people mean when they speak of Eternity, Omnipotence, God? What do they mean by the True, the Good, the Beautiful? Do these ‘great and thumping words’ relate to any objective truth, or are they empty rhetoric invented to cheer or impress ourselves and others: the vague expressions of vague needs, wishes, fears, appetites of us, weak children of a day, who know little of (and matter less to) the vast, blind, indifferent, unintelligible, inscrutable, machine or power or flux or nothingness, on the skirts of whose darkness our brief lives flicker for a moment and are gone?

And if this is the true case of us and our lives and loves and all that we care for, then Why is it?

Ah, Love! Could you and I with Him conspire

To grasp this sorry Scheme of Things entire,

Would not we shatter it to bits – and then

Re-mould it nearer to the Heart’s Desire!

Why not? Why is there Evil in the world?

Such, in rapid and superficial survey, are the ultimate problems of existence; ‘riddles of the Sphinx’ which, in one shape or another, have puzzled men’s minds and remained without any final answer since history began, and will doubtless continue to puzzle and elude so long as mankind continues upon this planet.

But though it is true that (as contrasted with the special sciences) little progress has been made in philosophy: that we have not today superseded Plato and Aristotle in the sense in which modern medicine has superseded Hippokrates and Galen: yet, on the negative side and particularly in metaphysics, definite progress has been made.

Descartes’ Cogito ergo sum – ‘I think; therefore I exist’ – has been criticized not because its assumptions are too modest, but because they are too large. Logically it can be reduced to cogito, and even that has been shorn of the implied ego. That is to say, the momentary fact of consciousness is the only reality that cannot logically be doubted; for the mere act of doubting, being an act of consciousness, is of itself immediate proof of the existence of that which was to be the object of doubt.

Consciousness is therefore the fundamental reality, and all metaphysical systems or dogmas which found themselves on any other basis are demonstrably fantastic. In particular, materialistic philosophies of every kind and degree are fantastic.

But, because demonstrably fantastic, they are not therefore demonstrably false. We cannot, for instance, be reasonably driven to admit that some external substance called ‘matter’ is prior to or condition of consciousness; but just as little can we reasonably deny the possibility of such a state of things. For, logically, denial is as inadmissible as assertion, when we face the ultimate problems of existence outside the strait moment of consciousness which is all that certainly remains to us after the Cartesian analysis. Descartes, it is true, did not leave it at that. But he had cleared the way for Hume and Kant to show that, briefly, every assumption which he himself or any other metaphysician might produce like a rabbit from the hat must have been put into the hat before being brought out. In other words, the scientific method, applied to these problems and pressed to its logical implications, leads to an agnosticism which must go to the whole of experience, as Pyrrho’s did, and not arbitrarily stop short at selected limits, as did the agnosticism of the nineteenth century. It leads, therefore, to an attitude of complete and speechless scepticism.

If we think this conclusion a reductio ad absurdum, and would seek yet some touchstone for the false and the true, we must seek it elsewhere than in pure reason. That is to say (confining the argument to serious attitudes of speculation on the ultimate problems of existence), we must at that stage abandon the scientific attitude and adopt the poet’s. By the poet’s I mean that attitude which says that ultimate truths are to be attained, if at all, in some immediate way: by vision rather than by ratiocination.

How, then, is the poet to go to work, voyaging now in alternate peril of the Scylla and Charybdis which the Cartesian–Kantian criticism has laid bare – the dumb impotence of pure reason on the one hand, and on the other a welter of disorganized fantasy through which reason of itself is powerless to choose a way, since to reason (in these problems) ‘all things are possible’ and no fantasy likelier than another to be true?

Reason, as we have seen, reached a certain bed-rock, exiguous but unshakable, by means of a criticism based on credibility: it cleared away vast superfluities of baseless system and dogma by divesting itself of all beliefs that it was possible to doubt. In the same way, may it not be possible to reach a certain bed-rock among the chaos of fantasy by means of a criticism based not on credibility but on value?

No conscious being, we may suppose, is without desire; and if certain philosophies and religions have set up as their ideal of salvation and beatitude a condition of desirelessness, to be attained by an asceticism that stifles and starves every desire, this is no more than to say that those systems have in fact applied a criticism of values to dethrone all minor values, leaving only this state of blessedness which (notwithstanding their repudiation of desire) remains as (for their imagination at least) the one thing desirable. And in general, it can be said that no religion, no philosophy, no considered view of the world and human life and destiny, has ever been formulated without some affirmation, express or implied, of what is or is not to be desired: and it is this star, for ever unattained yet for ever sought, that shines through all great poetry, through all great music, painting, building, and works of men, through all noble deeds, loves, speculations, endurings and endeavours, and all the splendours of ‘earth and the deep sky’s ornament’ since history began, and that gives (at moments, shining through) divine perfection to some little living thing, some dolomite wall lighted as from within by the low red sunbeams, some skyscape, some woman’s eyes.

This then, whatever we name it – the thing desirable not as a means to something else, be that good or bad, high or low (as food is desirable for nourishment; money, for power; power, as a means either to tyrannize over other men or to benefit them; long life, as a means to achievement of great undertaking, or to cheat your heirs; judgement, for success in business; debauchery, for the ‘bliss proposed’; wind on the hills, for inspiration; temperance, for a fine and balanced life), but for itself alone – this, it would seem, is the one ultimate and infinite Value. By a procedure corresponding to that of Descartes when, by doubting all else, he reached through process of elimination something that he could not doubt, we have, after rejecting all things whose desirableness depends on their utility as instruments to ends beyond themselves, reached something desirable as an end in itself. What it is in concrete detail, is a question that may have as many answers as there are minds to frame them (‘In my Father’s house are many mansions’). But to deny its existence, while not a self-contradictory error palpable to reason (as is the denial of the Cartesian cogito), is to affirm the complete futility and worthlessness of the whole of Being and Becoming.