полная версия

полная версияThe modes of origin of lowest organisms

H. Charlton Bastian

The modes of origin of lowest organisms / including a discussion of the experiments of M. Pasteur

Having been compelled by the results of my investigations on the question of the Origin of Life to arrive at conclusions adverse to generally received opinions, I found that several persons having high authority in matters of science, were little disposed to assent to these views. To a great extent this seemed due to the fact that a distinguished chemist had previously gone over some of the same ground, and had arrived at precisely opposite conclusions. M. Pasteur has been long known as an able and brilliant experimenter, and some of his admirers seem to regard him as an almost equally faultless reasoner.

Renewed and prolonged experimentation having tended to demonstrate the truth of my original conclusions, and to convince me of the utter untenability of M. Pasteur’s views, it seemed that the best course to pursue would be, at first, to endeavour to show into what errors of reasoning M. Pasteur had fallen, and also how his conclusions were capable of being reversed by the employment of different experimental materials, and different experimental methods. Then, having presented, in a connected form, evidence which might suffice to shake the faith of all who preserved a right of independent judgment, one might hope to have paved the way for the reception of new views – even though they were adverse to those of M. Pasteur. The present volume contains, indeed, only a fragment of the evidence which will be embodied in a much larger work – now almost completed – relating to the nature and origin of living matter, and in favour of what is termed the physical doctrine of Life.

The question of the mode of origin of Living Matter, is inextricably mixed up with another problem as to the cause of fermentation and putrefaction. M. Pasteur’s labours were, at first, undertaken in order to solve the latter difficulty – to decide, in fact, between two rival hypotheses. It was held, on the one hand, that many ferments were mere dead nitrogenous substances, and that fermentation was a purely chemical process, for the initiation of which the action of living organisms was not necessary; whilst, on the other hand, it was also maintained that no fermentation could be initiated without the agency of living things – in fact, that all ferments were living organisms. The former may be called the physical theory of fermentation, of which Baron Liebig is the most prominent modern exponent; whilst the latter may be termed the vital theory of fermentation, and this is the doctrine of M. Pasteur. All the facts which I have to adduce, so far as the subject of fermentation is concerned, are wholly in favour of the views of Baron Liebig.

And, the conclusions arrived at in this work are confirmed by the results of several unpublished experiments, in which living organisms have been taken from flasks that had, a few weeks before, been hermetically sealed and heated for a variable time to temperatures ranging from 260° F. to 302° F.

With the view of aiding some of my readers in their interpretation of the results of some of the experiments contained in this volume, I would call their attention to the following considerations. If fluids in vacuo (in hermetically-sealed flasks), which were clear at first, have gradually become turbid; and if on microscopical examination this turbidity is found to be almost wholly due to the presence of Bacteria or other organisms, then it would be sheer trifling gravely to discuss whether the organisms were living or dead, on the strength of the mere activity or languor of the movements which they may be seen to display. Can dead organisms multiply in a closed flask to such an extent as to make an originally clear fluid become quite turbid in the course of two or three days?

And if any one wishes to convince himself as to whether such turbidity can occur in a flask which is still hermetically sealed, let him take one that has been prepared in the manner I have elsewhere described, carefully heat the neck of it in a spirit-lamp flame, and see how the rapid in-bending of the red-hot glass testifies to the preservation of a partial vacuum within. The vacuum in such cases is only partially preserved, because of the emission of a certain amount of gases within the flask – such as invariably occurs during the progress of fermentation or putrefaction.

In these experiments with heated fluids in closed flasks, nothing is easier than to obtain negative results. The same kinds of infusions which – if care has been taken to obtain them strong enough – will in a few days teem with living organisms, often show no trace of living things after much longer periods, when the solutions are weak. Again, in those cases where only a few organisms exist in a solution which has been made the subject of experimentation, nothing is easier than by a perfunctory examination of the fluid to fail in finding any of these sparsely-distributed living organisms. Experiments, the results of which are positive, may, therefore, in the absence of sufficient care, be cited as negative; and experiments which would otherwise have been crowned with unmistakeably positive results, may be rendered wholly barren by the employment of infusions which have been carelessly made.

A word of explanation seems necessary with regard to the introduction of the new term Archebiosis. I had originally, in unpublished writings, adopted the word Biogenesis to express the same meaning – viz., life-origination or commencement. But in the mean time the word Biogenesis has been made use of, quite independently, by a distinguished biologist, who wished to make it bear a totally different meaning. He also introduced the word Abiogenesis. I have been informed, however, on the best authority, that neither of these words can – with any regard to the language from which they are derived – be supposed to bear the meanings which have of late been publicly assigned to them. Wishing to avoid all needless confusion, I therefore renounced the use of the word Biogenesis, and being, for the reason just given, unable to adopt the other term, I was compelled to introduce a new word, in order to designate the process by which living matter is supposed to come into being, independently of pre-existing living matter.

H. Charlton Bastian.Queen Anne Street, W.,

May 8, 1871.

THE MODES OF ORIGIN

OF

LOWEST ORGANISMS

The mode of origin of Bacteria, and, to a less extent, of Torulæ, has been much discussed of late, and many different views have been advocated on this subject by successive writers.

It is of much importance to bear in mind when such views are under consideration, that a short time since nothing was positively known concerning the life-history of these organisms. However strongly, therefore, certain persons are inclined to rely upon the analogy which is supposed to obtain between these doubtful cases, and the multitudes of known cases – in which it can be shown that organisms are the offspring of pre-existing organisms – it must always be borne in mind that in many of the doubtful cases, where the simplest organisms are concerned, there is also an analogical argument of almost equal weight adducible in favour of their de novo origination – after a fashion, and under the influence of laws similar to those by which crystals arise. To rely too exclusively upon an argument from analogy is always perilous: it is more than usually so, however, in a case like this, where what is practically an opposing analogy may be deemed to speak just as authoritatively in an opposite direction.

There is one consideration, moreover, which deserves to be pointed out here, and which does not seem to have occurred to most of those who so firmly pin their faith to the truth of the motto “omne vivum ex vivo.” The every-day experience of mankind, supplemented by the ordinary observations of skilled naturalists, does pretty fairly entitle us to arrive at a wide generalization, to the effect that some representatives of every kind of organism are capable of reproducing similar organisms. But, whilst this is all that the actual every-day experience of mankind warrants being said, and whilst there is in reality the widest possible gulf between such a generalization and that which is expressed by the motto “omne vivum ex vivo,” the latter formula has of late been spoken of as though it were the one which was in accordance with the daily experience of mankind, rather than the other, which gives expression to a generalization of a much narrower description. This experience, in reality, affords no evidence which could entitle us to place implicit belief in the formula “omne vivum ex vivo.”

Whilst we do know something about the ability which most organisms possess of reproducing similar organisms, we cannot possibly say, from direct observation, that every organism which exists has had a similar mode of origin, because the cases in which organisms may have originated de novo are the very cases in which their mode of origin must elude our actual observation. Such a statement, too, would be all the more dangerous, in the face of the other analogy, when it can actually be shown that some organisms do make their appearance in fluids after precisely the same fashion as crystals.

Although, therefore, there is a contradiction between the unwarrantable and ill-begotten formula, “omne vivum ex vivo,” and the doctrines of what has been called “Spontaneous Generation”; there is no contradiction whatever between such doctrines and the only generalization which we are really warranted in arriving at, to the effect that some representatives of every kind of organism are capable of reproducing similar organisms.

Bacteria, Torulæ, or other living things which may have been evolved de novo, when so evolved, multiply and reproduce just as freely as organisms that have been derived from parents.

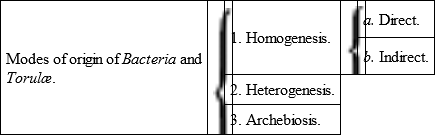

The views as to the origin of Bacteria and Torulæ which are most worthy of attention, may be thus enumerated: —

a. That they are independent organisms derived by fission or gemmation from pre-existing Bacteria and Torulæ.

b. That they represent subordinate stages in the life-history of other organisms (fungi), from some portion of which they have derived their origin, and into which they again tend to develop.

c. That they may have a heterogeneous mode of origin, owing to the more complete individualization of minute particles of living matter entering into the composition of higher organisms, both animal and vegetal.

d. That they may arise de novo in certain fluids containing organic matter, independently of pre-existing living things (Archebiosis).

I shall make some remarks concerning each of these views, though the evidence I have to adduce mainly concerns the possibility of the origin of Bacteria and Torulæ in the way last alluded to, viz., by Archebiosis.

The third mode of origin is what is called Heterogenesis; whilst the first and second modes are the representatives of more familiar processes, included under the head of Homogenesis. Thus, in accordance with the first view, Bacteria may be regarded as low organisms having a distinct individuality of their own and multiplying by a process of fission – thus affording instances of what I propose to term direct Homogenesis. Whilst, in accordance with the second view, Bacteria are supposed to represent merely one stage in the life-history of higher organisms, which are therefore reproduced by an indirect or cyclical process of Homogenesis.

The possible modes of origin of Bacteria and Torulæ may, therefore, be tabulated as follows: —

I. Homogenetic Mode of Origin of Bacteria and Torulæ

Bacteria and Torulæ being already in existence, they may, undoubtedly, reproduce organisms similar to themselves by processes of fission and gemmation – in the same way that other low protistic organisms propagate their kind. Although so many reasons rendered this view probable, it was some time before I was able actually to confirm it by personal observations in the case of Bacteria. In the ordinary microscopical examination of portions of an infusion containing these organisms, an observer may watch for hours and never see a single instance of such fission occurring. His attention is apt to be distracted by the number of organisms which are constantly flitting before his view, and he is, moreover, perhaps apt to pay particular attention to those which seem by their movements to be most obviously alive.

I have observed the process most plainly when a few Bacteria have been enclosed in a single drop of fluid, pressed into a very thin stratum, in a “live-box” kept at a temperature of about 90° Fahr. by resting on one of Stricker’s warm-water chambers placed on the stage of the microscope. Under these conditions, I have seen a Bacterium of moderate size divide into two, and each of these into two others somewhat smaller, in the course of fifteen minutes.

It is still more worthy of remark, that in all cases (so far as I have been able to observe), this, the most certain sign of vitality which such organisms are capable of manifesting, is shown by those which, from their stillness, might be considered dead. The Bacteria which are about to divide are generally either motionless,1 or merely present slight oscillating movements. The separation is quickly brought about at the joint, so that the original organism divides into two equal portions; and these, lying close together, soon develop a new construction as they grow, through which a further division may occur.

That the Bacteria which reproduce should be in a comparatively quiescent condition, seems not difficult to understand. Such rudimentary organisms do not appear to possess cilia or other locomotory appendages: their movements are, therefore, in all probability dependent upon the mere molecular changes which are taking place within them, and upon which their life and nutrition depend. The process of fission must, however, be considered as the result of a new effort at equilibrium, which has, perhaps, been necessitated by molecular changes that have occurred during a preceding period of growth. The living matter which is no longer able to exist round a single centre, re-arranges itself around two centres, – as a result of which, fission occurs. It seems only natural, therefore, that whilst this active work of molecular re-arrangement is going on, those other molecular movements which occasion the actual locomotion of the organism from place to place, should be more or less interfered with.

This is the one and only mode of multiplication of Bacteria and of Torulæ which is actually known to occur; and such a limitation is in accordance with the more general fact, that processes of fission or gemmation are the only means of reproduction that are known to occur in the lower kinds of organisms, belonging to the PROTISTIC kingdom.

However well this process of fission may have been established, as a frequent mode of reproduction of Bacteria, such a fact does not lend any support to the notion that these are necessarily distinct and independent organisms. Torulæ (of which beer-yeast is the most familiar example) may similarly undergo this process of mere vegetative repetition to an indefinite extent, whilst only some of the products develop into fungi. The gonidia of lichens may also reproduce indefinitely in this fashion, and only some of the products of multiplication may go on to the production of lichens similar to that from which the gonidia had been derived.

It is a fact, however, admitted by many, and which any patient microscopist is capable of verifying for himself, that some Bacteria do develop into Leptothrix filaments, and that these are capable of passing into a dissepimented mycelial structure of larger size and undoubtedly fungus nature – from which fructification of various kinds may be produced. Some Bacteria may therefore develop into some fungi, just as certainly as some Torulæ may develop into other fungi, or, just as surely as some multiplying gonidia may develop into lichens.

In order to prove, however, that the Bacteria which happen to go through this development into Leptothrix and thence into fungi, are strictly to be considered as necessary links in the life-history of fungi, it would be essential for the person holding such views, to show that Bacteria could not arise independently – or at least that no independently evolved Bacteria could develop through Leptothrix-forms into a fungus. And, similarly, for the other kinds of organisms: in order to establish that the Torula cell is a necessary link in the life-history of certain fungi, or the gonidial cell a necessary link in the life-history of lichens, it would be necessary to show that Torulæ or gonidial cells could not originate de novo– that no independently evolved Torula or gonidial cell could develop into a fungus or a lichen.

An easier position to establish would be, that the Bacterium or the Torula were occasionally links in the life-history of fungi, or that the gonidial cell was an occasional link in the life-history of a lichen. This doctrine would leave the other more difficult problems, – as to the possible existence of supplementary modes of origin for such organisms by Heterogenesis or by Archebiosis – perfectly open questions.

To establish the position that Bacteria are occasional links in the life-history of fungi, it would be only necessary to show that some of the Bacteria which develop into fungi through Leptothrix have derived their origin from pre-existing fungi. This is the view which Hallier2 has endeavoured to establish; it is also the doctrine of M. Polotebnow,3 and one, moreover, to which Professor Huxley4 inclines. Even this mode of origin for Bacteria, however, has not been so decisively established as might be desired. With regard to Torulæ, we do possess sufficient evidence tending to show that some of them may arise from pre-existing fungi, and we are equally certain that some gonidial cells are thrown off from lichens. The analogical evidence is, therefore, in favour of the view that minute particles which are budded off from the mycelium of certain fungi, may subsequently lead an independent existence, and multiply in the form of Bacteria– although many of the cases in which such buds seem to be given off, may be merely cases in which co-existing Bacteria have become adherent to fungus filaments or to Torulæ.5

But, with reference to these supposed cases of budding, and also to those others in which the contents of a spore or sporangium break up into what Professor Hallier calls “micrococci” (which are generally incipient Bacteria), it would be difficult for us to decide whether such processes are normal or abnormal. When we have to do with such organisms, in fact, there may be the nicest transitions between what is called Homogenesis, and what, when occurring in other organisms, we term Heterogenesis. It may be that the production of such “micrococci” from the spore or sporangium of the fungus is not an invariable incident in the life-history of the species, but rather an occasional result of the influence of unusual conditions, or of failing vigour on the part of the organism. In this latter case we should have to do with a process of Heterogenesis; although, as I have just stated, in respect to such low and changeable organisms, scarcely any distinct line of demarcation can be drawn between Homogenesis and Heterogenesis.

The evidence seems, therefore, against the notion that Bacteria or Torulæ are ordinary, independent living things, which merely reproduce their like.

That some Bacteria are produced from pre-existing Bacteria, just as some Torulæ are derived from pre-existing Torulæ, may, it is true, be considered as settled. But, so far as we have yet considered the subject, there may be just as good evidence to show that Bacteria and Torulæ are capable of arising de novo, as there is that some of them are capable of developing into fungi.

If this were the case, such types could only be regarded as the most common forms assumed by new-born specks of living matter; and, by reason of their origin – which would entail an absence of all hereditary predisposition – they might be supposed to be capable of assuming higher developmental forms.

Now, as a matter of fact, worthy of arresting our attention, we do find that some Bacteria are capable of growing into Leptothrix, whilst this is able to develop continuously into a fungus; just as we also know that some Torulæ are capable of growing into other fungi.

Should it be established, therefore, that Bacteria and Torulæ are capable of arising de novo, the facts concerning their mutability are harmonious enough with theoretical indications.

But, as I have before indicated, although it is quite true that some Bacteria develop into fungi, such forms may constitute no necessary links in the life-history of other fungi. I have suggested that in those (occasional) cases in which they do occur as links in the life-history of fungi, there is room for doubt whether these Bacteria are to be considered as normal products, or as abnormal results (heterogeneous offcasts), brought about by some unusual conditions acting upon the parent fungus. That is to say, we may be doubtful whether in such a case their origin ought to be considered Homogenetic or Heterogenetic. It may be that many of the lower fungi are such changeable organisms, and so prone to respond to the various “conditions” acting upon them (which would be almost certainly the case if they had been developed from a Bacterium in two or three days – the Bacterium itself having been evolved de novo) that no very valid distinction can here be drawn between Homogenesis and Heterogenesis. Our whole point of view, in fact, concerning such fungi as are seen to develop through Leptothrix forms from Bacteria must be entirely altered, if it is once conceded that Bacteria may arise de novo. Such simple Mucedineæ would then have to be regarded as mere upstart organisms only a few removes from dead matter, and – in view of the greater molecular mobility of living matter – capable of being modified in shape and form even more than the most changeable crystals under the influence of altering “conditions.” We should have no longer to do with the members of a stable species, which had been reproducing its like through countless geologic ages anterior to the advent of man upon the earth. Indeed, in order to reconcile such a possibility with the seemingly contradictory fact of the known extreme changeability of these lower forms of life, we hear only vague hints thrown out about our imperfect knowledge of the “limits within which species may vary.” As if, in the face of what we do know concerning hereditary transmission, this changeability did not make it almost impossible to conceive that there should have been an unbroken series of such organisms since that remote epoch of the earth’s history, when the first organisms of the kind made their appearance. It does not seem to me that the presumed permanence of a very changeable organism is consistent with, or rendered more explicable by, the supposition that some representatives of the species have constantly been undergoing progressive modifications which have been successively perpetuated by inheritance, in the shape of distinct specific forms. Why should some be presumed to have undergone so much change, whilst others (presenting an equal and an extreme degree of modifiability, even to the present day) are supposed to have preserved the same specific form through a countless series of changing influences?