полная версия

полная версияSocial England under the Regency, Vol. 1 (of 2)

Of course, this style of argument availed him nothing with the jury, who, after a very brief consultation, brought him in "Guilty." Sentence of death was passed upon him, and, as there was very little sickly sentimentality in those days, as to carrying out the penalty of the law, he was duly hanged on the 18th of May: his body being given over to the surgeons for dissection. It is said that after his body was opened, his heart continued its functions for four hours; in other words, that he was living for that time.

The day after Mr. Perceval's assassination, the Prince Regent sent a Message to Parliament recommending a provision being made for Mrs. Perceval and her family, and an annuity of £2,000 was granted her, together with a sum of £30,000 to her family. These were voted unanimously, and two other votes were passed by large majorities – one to provide a monument to his memory in Westminster Abbey, the other granting to his eldest son, Spencer Perceval, who was just about to go to College, an annuity of £1,000, from the day of his father's death, and an additional £1,000 yearly, on the decease of his mother.

One would have thought that there could have been but one feeling throughout the nation, that of horror, at this dastardly murder, but one town was the base exception. When the news of his murder reached Nottingham, a numerous crowd publicly testified their joy by shouts, huzzas, drums beating, flags flying, bells ringing, and bonfires blazing. The Military being called out, and the Riot Act read, peace was restored.

CHAPTER VII

French Prisoners of War – Repeal of the "Orders in Council" – Rejoicings for the Victory of Salamanca – Saturnalia thereatThere was always more or less trouble with the French Prisoners of War during the year – as we know, many escaped, and small blame to them – whilst many officers deliberately and disgracefully broke their parole and got away. Six Prisoners escaped from Edinburgh Castle, made for the sea, found a boat, and, sailing up the Firth, got as far as Hopetoun House, where they landed, intending to go to Glasgow by land, but the Commandant of the Linlithgow Local Militia had information that several men had been seen skulking about Lord Hopetoun's plantations, and, after some trouble, they were caught, lodged in Linlithgow gaol, and then sent back to Edinburgh.

One gained his freedom by an act of gallantry, early in February. "François Goyette, a French Prisoner, lately employed as a servant on board the hospital ship Pegase, has been released, and sent to France by the Transport Board, as a reward for his exertions in jumping overboard to the rescue of the Cook and boy of the Hydra frigate, when upset in her boat on Porchester Lake."

We see, by the following, how systematic they became in their methods of escaping: —

"Upwards of 1,000 French prisoners have escaped from this country during the war, and so many persons have lately been detected in assisting their escape, that those concerned have had a vehicle made for the conveyance of Frenchmen, to avoid suspicion or detection, exactly resembling a covered cart used by the Calico printers, with strong doors at each end, but with seats inside to hold a number of men. One of them was detected about a week since, in a very extraordinary way. Some Revenue Officers went into a public house near Canterbury, where two men were playing at cards, whom they suspected to be Frenchmen on their way to escape from this country. They communicated this suspicion to a magistrate, who informed them that, at that hour of the night (about eight o'clock), the Constable was generally intoxicated, and it would be of no use applying to him; but advised them to procure the assistance of some of the Military in the neighbourhood, which the officers accordingly did, and surrounded the house.

"The landlord refused to open the door, saying it was too late. The soldiers told him they were in search of deserters. A short time afterwards two men came out of the back door, and the Revenue Officers, suspecting they were two Frenchmen, secured them. Another came out directly afterwards, whom the soldiers stopped; he, also, was a Frenchman. They were conveyed away in Custody. This was a mere chance detection, as the two men whom the Revenue Officers had seen at Cards early in the evening proved, not Frenchmen, but tradesmen of the neighbourhood; and, while the officers were gone to the magistrate, and after the military, a cart, such as we have described, arrived at the house with four Frenchmen.

"The fourth man, who was some time in coming out, after the others, escaped into the London road, whither he knew the cart had returned, and overtook it; but the driver would not, for a considerable time, take him up, as he had only seen him in the night-time, till he made him understand that he was connected with one Webb, the driver's employer. It being ascertained that the three Frenchmen in custody, had been brought there in a cart, pursuit was made, and it was overtaken, and the driver and the Frenchman were taken into custody. They were examined before a magistrate, when it appeared, from the confession of the driver, &c., that the four Frenchmen were officers, who had broken their parole from Ashby de la Zouche. The Cart had been fitted up with a seat, to hold a number of Frenchmen. He was employed by Mr. Webb to drive the cart. The Frenchmen only got out of the cart at night to avoid observation. They stopped at bye-places, and made fires under hedges. At a place near Brentford, a woman connected with Webb made tea for them. They stopped on Beckenham Common to rest the horse, about ten o'clock at night, when, a horse-patrol passing at the time, suspected something to be wrong, but could not ascertain what. He insisted on the driver moving off; and when he was about putting the horse into the Cart, an accident happened which nearly led to their discovery. The Frenchmen all being at the back of the cart, the driver lost the balance, when he was putting in the horse, and the cart fell backwards, which caused the Frenchmen to scream violently; but it is supposed the patrol had gone too far to hear the noise. Webb was apprehended, and examined before a magistrate in Kent, but he discharged him. However, afterwards, the magistrate meeting with Webb, in Maidstone, where he was attending the assize on a similar charge, he took him into custody."

What was it made these French Officers so dishonour themselves by breaking their parole? The very fact of their being on parole, intimates a certain amount of freedom. It must have been either a dull moral perception, and the utter want of all the feelings and instincts of a gentleman, or else ungovernable nostalgia, which blunted their sense of honour. Here is a pretty list, June 30, 1812: —

"The number of French commissioned Officers, and masters of Privateers and Merchantmen, who have broken their parole in the last three years ending 5 June is 692, of whom 242 have been retaken, and 450 escaped. A considerable number of officers have, besides, been ordered into confinement, for various other breaches of their parole engagements."

Something had to be done to stop this emigration, so the Government gave orders to seize all galleys of a certain description carrying eight oars: 17 were seized at Deal, and 10 at Folkestone, Sandgate, &c. They must have been built for smuggling, and illicit purposes, for they were painted so as to be perfectly invisible at night, and were so slightly built, and swift, that in those days of no steamers, no craft could catch them. However, the punishment, if caught, for aiding their escape, was severe, as three men found to their cost. They were sentenced to two years' imprisonment, and two of them "to be placed in and upon the pillory on the sea-shore, near the town of Rye, and, as near as could be, within sight of the French Coast, that they might be viewed, as his lordship observed, by those enemies of their country, whom they had, by their conduct, so much befriended."

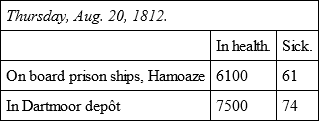

The French papers had accused us of ill-treating our prisoners, so that a disclaimer was necessary: —

"French Prisoners. – As a proof of the good treatment of the prisoners of war in this country, the following comparative statement of those sick and in health will be the best answer to the calumnies of the Moniteur: —

"This small percentage of sick, is not the common average of persons not confined as Prisoners of War. At Dartmoor 500 prisoners, such as labourers, carpenters, smiths, &c., are allowed to work from sun-rise to sun-set; they are paid fourpence and sixpence per day, according to their abilities, and have each their daily rations of provisions, viz., a pound and a half of bread, half a pound of boiled beef, half a pound of cabbage, and a proportion of soup and small beer. They wear a tin plate in their Caps, with the title of the trade they are employed in, and return every evening to the depôt to be mustered."

They had a rough sense of justice among themselves, their punishments to delinquents not quite coming up to the rigorous "mort aux voleurs," but still very severe. Here is a case: The French prisoners who were brought to the depôt at Perth, on August 13th, from Dundee, were lodged, the preceding night, in the Church at Inchture, where, it is said, they contrived to draw many of the nails from the seats, and break a number of the panes of the windows; and one of their number stole the two mort-cloths, or palls, belonging to the Church. The beadle being sent after them to the depôt, the theft was instantly discovered, which so incensed the prisoners against the thief, that they called out to have him punished, and asked permission to do so by a Court-martial. Having held this Court, they ordered him a naval flogging of two dozen, with the end of a hard rope. The Culprit was tied to a lamp-post, and, with the first lash, the blood sprung. The punishment went on to 17 lashes, when the poor man fainted away, but he had the other 7 at another time.

They kicked over the traces sometimes, as we learn by the Annual Register, September 8th: —

"The French prisoners at Dartmoor depôt, on Sunday last, had worked themselves up to the highest pitch of rage, at having a pound and a half of biscuit, and not bread, per day. The use of biscuit, it is to be observed, was to be discontinued as soon as the bakehouse had been rebuilt; but the Frenchmen were absolutely deaf to remonstrances. A detachment of the Cheshire militia, and of the South Gloucester regiment, was drawn up on the walls surrounding the prison; and, although they had loaded their pieces with ball, the prisoners appeared undaunted, and insulted them in the grossest terms. A sentinel on duty had the bayonet wrenched off his piece, yet nobly reserved his fire; an officer, however, followed the Frenchman, struck him over the shoulder with his sword, and brought off the bayonet. The Frenchmen even bared their breasts to the troops, and seemed regardless of danger.

"The number of prisoners is about 7,500; and so menacing was their conduct, that an express was sent off to Plymouth Dock, at eleven o'clock on Sunday night, soliciting immediate assistance. Three pieces of Artillery were, in consequence, sent off early on Monday morning; and, on their arrival, at the principal gate, the bars of which, of immense size, had been previously broken by stones hurled against them by the insurgents, they were placed in such directions as to command the whole of the circle which the prison describes. This had the desired effect, and order was restored. It is to be noticed that the allowance of biscuit, at which these men had so indignantly spurned, is precisely the same as that which is served out to our own sailors and marines."

At another time (Sunday, October 11th) the Ganges prison ship, at Portsmouth, with 750 prisoners on board, was set on fire by one of them, and had actually a great hole burned in her, before the fire was discovered. The incendiary was soon detected, and put in irons; he confessed his guilt, and declared it was his intention to destroy himself and companions, who were tired of confinement. To the credit of his compatriots, they all helped to extinguish the flames, and were, with difficulty, restrained from lynching the offender.

One pretty little story anent them, and I have done. A prisoner, located at Perth, was released, on account of his humanity. At the storming of Badajoz, General Walker fell at the head of his brigade, and was found by this young Frenchman lying wounded, and bleeding, in the breach. In his arms he bore the General to a French Hospital, where he was cured. General Walker gave him his address, and promised to serve him, if ever it lay in his power. The fortune of war brought the young man, a captive, to England, and, on his application to his friend the General, the latter so used his influence as to procure his release.

An act was done in this year which removed many restrictions from our trade, and promoted the manufacturing industry of the Country. It was all very well to be victorious in war, but the fact of being at war, more especially with opponents whose great efforts were to cripple the trade of the Nation, and thus wither the sinews by which war is greatly maintained, was felt throughout all classes of the Manufacturing Interest all over the Country, a power which was then beginning to make itself felt. The Act of which I speak, was the abolition of the Orders in Council which prohibited trade with any port occupied by the French, being a reprisal for Napoleon's Berlin and Milan Decrees, which interdicted commerce with England.

Petitions poured into Parliament in favour of their abrogation, and on the 24th of April Lord Liverpool laid on the table of the House of Lords, the following

"DECLARATION of the Court of Great Britain respecting the Orders in Council"At the Court at Carlton-house the 23rd day of April, 1812. Present his Royal Highness the Prince Regent in Council.

"Whereas his Royal Highness the Prince Regent was pleased to declare, in the name, and on the behalf of his Majesty, on the 21st day of April, 1812: 'That if at any time hereafter, the Berlin and Milan Decrees shall, by some authentic act of the French Government, publicly promulgated, be absolutely and unconditionally repealed, then, and from thenceforth, the Order in Council of the 7th of January, 1807, and the Order in Council of the 26th of April, 1809, shall without any further Order be, and the same are hereby declared from thenceforth to be, wholly and absolutely revoked."

On this being known, there were great rejoicings throughout the Country, especially at Sheffield, Leeds, and other manufacturing towns; the beneficial effects of the alteration became immediately apparent, there being more purchases made at the Cloth Hall at Leeds, in one day, than had been known for many years. At Liverpool 1,500,000 yards of bounty goods were shipped in one week, worth £125,000, and 2,500,000 were in progress of shipment. In the same week £12,00 °Convoy duty, at 4 per cent., was paid, indicating further shipments to the amount of £300,000, at the same port. The wages of Spinners, &c., advanced at once, in some cases as much as 2s. 3d. a week.

But all rejoicings were not so quiet – witness those which took place in London in honour of the Victory of Salamanca, when Wellington totally defeated the French Army under Marshal Marmont, July 22, 1812. The French left in the hands of the British 7,141 prisoners, 11 pieces of cannon, 6 stands of colours, and 2 eagles.

The Illuminations in London took place on August 17th and two following days, but they seem to have been of the usual kind. If the sightseers could not get hold of the hero of the day, they managed to lay hands on the Marquis Wellesley, his brother, who was driving about, looking at the illuminations; and, having taken the horses out of his carriage, they dragged him about the streets; finally, and luckily, depositing him at Apsley House. After this, they returned down Piccadilly, calling out for lights, which had a little time before been brilliant, but since had gone out. The inhabitants got from their beds and showed candles, but this did not satisfy the mob, who set to work demolishing the windows with sticks, brick-bats, stones, &c., to the great danger of life and limb.

Some glass, in Mr. Coutts's house, which cost £4 10s. a square (for plate glass was very dear then) was broken, as were also several windows at Sir Francis Burdett's, and yet both had been well lighted throughout the night. This disgraceful scene was kept up till past three a.m., and damage was done, estimated at five or six hundred pounds.

On the third and last night of their Saturnalia the outrages were, perhaps, worse than before. Not only were fire-arms freely discharged, and fireworks profusely scattered, but balls of tow, dipped in turpentine, were thrown among crowds and into carriages; horses ran away in affright – carriages were overturned – and many deplorable accidents ensued in broken limbs and fractured skulls. Here are a few accidents. In Bow Street, a well-dressed young lady had her clothes set in a blaze. In the Strand, at one time, three women were on fire, and one burned through all her clothes, to her thigh. Likewise in the Strand, a hackney coach, containing two ladies and two gentlemen, was forced open by the mob, who threw in a number of fireworks, which, setting fire to the straw at the bottom of the coach, burned an eye of one of the gentlemen, his coat, and breeches; one of the ladies had her pelisse burned, and the other was burned across the breast. In St. Clement's Churchyard, a woman, of respectable appearance, hearing a blunderbuss suddenly discharged near her, instantly dropped down, and expired.

Apropos of Salamanca, there was a little jeu d'esprit worth preserving.

"Salamanca LobstersThough of Soldiers, by some in derision 'tis said,They are Lobsters, because they are cloathed in red,Yet the maxim our army admit to be true,As part of their nature, as well as their hue;A proof more decisive, the world never saw,For every man in the Field had 'Eclat.'"On the 30th of September, there was a great military function, in depositing the captured French Eagles in Whitehall Chapel. They were five in number, two taken at Salamanca, two at Madrid, and one near Ciudad Rodrigo.

CHAPTER VIII

Chimney-sweeps – Climbing boys – Riot at Bartholomew Fair – Duelling – War with France – Declaration of war between England and America – Excommunication for bearing false witness – Early Steam Locomotives – Margate in 1812 – Resurrection men – Smithfield Cattle ClubThe Social life of a nation includes small things, as well as great, deposition of Eagles, and Chimney-sweeps, and the latter have been looked after, by the legislature, not before the intervention of the law was needed. In 1789, 28 Geo. III., an Act was passed to regulate Chimney-sweeping. In 1834, another Act regulated the trade, and the apprenticeship of Children. Again, by 3 and 4 Vic. cap. 85, it was made illegal for a master sweep to take as apprentice, any one under sixteen years of age, and the Act further provided that no one, after the 1st of July, 1842, should ascend a chimney unless he were twenty-one years of age. In 1864 the law was made more stringent, and even as late as 1875 38 and 39 Vic. cap. 70, an Act was passed "for further amending the Law relating to Chimney Sweepers." That all this legislation was necessary is partially shown by a short paragraph of the date 7th of August: "Yesterday, Charles Barker was charged at Union Hall10 with kidnapping two young boys, and selling them for seven shillings, to one Rose, a chimney sweep at Kingston." And, again, the 25th of August: —

"An interesting occurrence took place at Folkingham.11 A poor woman who had obtained a pass billet to remain there all night, was sitting by the fire of the kitchen of the Greyhound Inn, with an infant child at her breast, when two chimney sweeps came in, who had been engaged to sweep some of the chimneys belonging to the inn early next morning. They were, according to custom, treated to a supper, which they had begun to eat, when the younger, a boy about seven years of age, happening to cast his eyes upon the woman, (who had been likewise viewing them with a fixed attention from their first entrance,) started up, and exclaimed in a frantic tone – 'That's my mother!' and immediately flew into her arms.

"It appears that her name is Mary Davis, and that she is the wife of a private in the 2nd Regiment of Foot-guards, now serving in the Peninsula; her husband quitted her to embark for foreign service on the 20th of last January, and on the 28th of the same month she left her son in the care of a woman who occupied the front rooms of her house, while she went to wash for a family in the neighbourhood: on her return in the evening, the woman had decamped with her son, and, notwithstanding every effort was made to discover their retreat, they had not since been heard of: but having lately been informed that the woman was a native of Leeds, she had come to the resolution of going there in search of her child, and with this view had walked from London to Folkingham (106 miles) with an infant not more than six weeks old in her arms.

"The boy's master stated, that about the latter end of last January, he met a woman and boy in the vicinity of Sleaford, where he resides. She appeared very ragged, and otherwise much distressed, and was, at that time, beating the boy most severely; she then accosted him (the master) saying she was in great distress, and a long way from home; and after some further preliminary conversation, said, if he would give her two guineas to enable her to get home, she would bind her son apprentice to him; this proposal was agreed to, and the boy was regularly indentured, the woman having previously made affidavit as to being his mother. This testimony was corroborated by the boy himself, but, as no doubt remained in the mind of any one respecting the boy's real mother, his master, without further ceremony, resigned him to her. The inhabitants interested themselves very humanely in the poor woman's behalf, by not only paying her coach fare back to London, but also collecting for her the sum of £2 5s."

Among the home news of 1811, I mentioned Bartholomew Fair; but, for rowdyism, the fair of 1812 seems to have borne the palm: —

"The scene of riot, confusion, and horror exhibited at this motley festival, on this night, has seldom, if ever, been exceeded. The influx of all classes of labourers who had received their week's wages, and had come to the spot, was immense. At ten o'clock every avenue leading through the conspicuous parts of the fair was crammed, with an impenetrable mass of human creatures. Those who were in the interior of the crowd, howsoever distressed, could not be extricated; while those who were on the outside, were exposed to the most imminent danger of being crushed to death against the booths. The females, hundreds of whom there were, who happened to be intermixed with the mob, were treated with the greatest indignity, in defiance of the exertions of husbands, relatives, or friends. This weaker part of the crowd, in fact, seemed to be, on this occasion, the principal object of persecution, or, as the savages who attacked them, were pleased to call it, of fun. Some fainted, and were trodden under foot, while others, by an exertion, almost supernatural, produced by an agony of despair, forced their way to the top of the mass, and crept on the heads of the people, until they reached the booths, where they were received and treated with the greatest kindness. We lament to state that many serious accidents in consequence occurred; legs and arms innumerable were broken, some lives were lost, and the surgeons of St. Bartholomew's Hospital were occupied the whole of the night in administering assistance to the unfortunate objects who were continually brought in to them.

"The most distressing scene that we observed arose from the suffocation of a child about a twelvemonth old, in the arms of its mother; who, with others, had been involved in the crowd. The wretched mother did not discover the state of her infant until she reached Giltspur Street, when she rent the air with her shrieks of self-reproach: while her husband, who accompanied her, and who had the appearance of a decent tradesman, stood mute with the dead body of his child in his arms, which he regarded with a look of indescribable agony. Such are the heartrending and melancholy scenes which were exhibited, and yet this forms but a faint picture of the enormities and miseries attendant upon this disgraceful festival."