полная версия

полная версияA Visit to the Philippine Islands

The apartments, as suited to a tropical climate, are large, and many European fashions have been introduced: the walls covered with painted paper, many lamps hung from the ceiling, Chinese screens, porcelain jars with natural or artificial flowers, mirrors, tables, sofas, chairs, such as are seen in European capitals; but the large rooms have not the appearance of being crowded with superfluous furniture. Carpets are rare – fire-places rarer.

Among Europeans the habits of European life are slightly modified by the climate; but it appeared to me among the Spaniards there were more of the characteristics of old Spain than would now be found in the Peninsula itself. In my youth I often heard it said – and it was said with truth – that neither Don Quixote nor Gil Blas were pictures of the past alone, but that they were faithful portraits of the Spain which I saw around me. Spain had then assuredly not been Europeanized; but fifty years – fifty years of increased and increasing intercourse with the rest of the world – have blotted out the ancient nationality, and European modes, usages and opinions, have pervaded and permeated all the upper and middling classes of Spanish society – nay, have descended deep and spread far among the people, except those of the remote and rural districts. There is little now to distinguish the aristocratical and high-bred Spaniard from his equals in other lands. In the somewhat lower grades, however, and among the whole body of clergy, the impress of the past is preserved with little change. Strangers of foreign nations, principally English and Americans, have brought with them conveniences and luxuries which have been to some extent adopted by the opulent Spaniards of Manila; and the honourable, hospitable and liberal spirit which is found among the great merchants of the East, has given them “name and fame” among Spanish colonists and native cultivators. Generally speaking, I found a kind and generous urbanity prevailing, – friendly intercourse where that intercourse had been sought, – the lines of demarcation and separation between ranks and classes less marked and impassable than in most Oriental countries. I have seen at the same table Spaniard, mestizo and Indian – priest, civilian and soldier. No doubt a common religion forms a common bond; but to him who has observed the alienations and repulsions of caste in many parts of the Eastern world – caste, the great social curse – the blending and free intercourse of man with man in the Philippines is a contrast well worth admiring. M. Mallat’s enthusiasm is unbounded in speaking of Manila. “Enchanting city!” he exclaims; “in thee are goodness, cordiality, a sweet, open, noble hospitality, – the generosity which makes our neighbour’s house our own; – in thee the difference of fortune and hierarchy disappears. Unknown to thee is etiquette. O Manila! a warm heart can never forget thy inhabitants, whose memory will be eternal for those who have known them.”

De Mas’ description of the Manila mode of life is this: – “They rise early, and take chocolate and tea (which is here called cha); breakfast composed of two or three dishes and a dessert at ten; dinner at from two to three; siesta (sleep) till five to six; horses harnessed, and an hour’s ride to the pasco; returning from which, tea, with bread and biscuits and sweets, sometimes homewards, sometimes in visit to a neighbour; the evening passes as it may (cards frequently); homewards for bed at 11 P.M.; the bed a fine mat, with mosquito curtains drawn around; one narrow and one long pillow, called an abrazador (embracer), which serves as a resting-place for the arms or the legs. It is a Chinese and a convenient appliance. No sheets – men sleep in their stockings, shirts, and loose trousers (pajamas); the ladies in garments something similar. They say ‘people must always be ready to escape into the street in case of an earthquake.’” I certainly know of an instance where a European lady was awfully perplexed when summoned to a sudden flight in the darkness, and felt that her toilette required adjustment before she could hurry forth.

Many of the pueblos which form the suburbs of Manila are very populous. Passing through Binondo we reach Tondo, which gives its name to the district, and has 31,000 inhabitants. These pueblos have their Indian gobernadorcillos. Their best houses are of European construction, occupied by Spaniards or mestizos, but these form a small proportion of the whole compared with the Indian Cabánas. Tondo is one of the principal sources for the supply of milk, butter, and cheese to the capital; it has a small manufacturing industry of silk and cotton tissues, but most of the women are engaged in the manipulation of cigars in the great establishments of Binondo. Santa Cruz has a population of about 11,000 inhabitants, many of them merchants, and there are a great number of mechanics in the pueblo. Near it is the burying-place of the Chinese, or, as they are called by the Spaniards, the Sangleyes infieles.

Santa Cruz is a favourite name in the Philippines. There are in the island of Luzon no less than four pueblos, each with a large population, called Santa Cruz, and several besides in others of the Philippines. It is the name of one of the islands, of several headlands, and of various other localities, and has been carried by the Spaniards into every region where they have established their dominion. So fond are they of the titles they find in their Calendar, that in the Philippines there are no less than sixteen places called St. John and twelve which bear the name of St. Joseph; Jesus, Santa Maria, Santa Ana, Santa Caterina, Santa Barbara, and many other saints, have given their titles to various localities, often superseding the ancient Indian names. Santa Ana is a pretty village, with about 5,500 souls. It is surrounded with cultivated lands, which, being irrigated by fertilizing streams, are productive, and give their wonted charm to the landscape – palms, mangoes, bamboos, sugar plantations, and various fruit and forest trees on every side. The district is principally devoted to agriculture. A few European houses, with their pretty gardens, contrast well with the huts of the Indian. Its climate has the reputation of salubrity.

There is a considerable demand for horses in the capital. The importation of the larger races from Australia has not been successful. They were less suited to the climate than the ponies which are now almost universally employed. The Filipinos never give pure water to their horses, but invariably mix it with miel (honey), the saccharine matter of the caña dulce, and I was informed that no horse would drink water unless it was so sweetened. This, of course, is the result of “education.” The value of horses, as compared with their cost in the remoter islands, is double or treble in the capital. In fact, nothing more distinctly proves the disadvantages of imperfect communication than the extraordinary difference of prices for the same articles in various parts of the Archipelago, even in parts which trade with one another. There have been examples of famine in a maritime district while there has been a superfluity of food in adjacent islands. No doubt the monsoons are a great impediment to regular intercourse, as they cannot be mastered by ordinary shipping; but steam has come to our aid, when commercial necessities demanded new powers and appliances, and no regions are likely to benefit by it more than those of the tropics.

The associations and recollections of my youth were revived in the hospitable entertainment of my most excellent host and the courteous and graceful ladies of his family. Nearly fifty years before I had been well acquainted with the Spanish peninsula – in the time of its sufferings for fidelity, and its struggles for freedom, and I found in Manila some of the veterans of the past, to whom the “Guerra de Independencia” was of all topics the dearest; and it was pleasant to compare the tablets of our various memories, as to persons, places and events. Of the actors we had known in those interesting scenes, scarcely any now remain – none, perhaps, of those who occupied the highest position, and played the most prominent parts; but their names still served as links to unite us in sympathizing thoughts and feelings, and having had the advantage of an early acquaintance with Spanish, all that I had forgotten was again remembered, and I found myself nearly as much at home as in former times when wandering among the mountains of Biscay, dancing on the banks of the Guadalquivir, or turning over the dusty tomes at Alcalá de Henares.3

There was a village festival at Sampaloc (the Indian name for tamarinds), to which we were invited. Bright illuminations adorned the houses, triumphal arches the streets; everywhere music and gaiety and bright faces. There were several balls at the houses of the more opulent mestizos or Indians, and we joined the joyous assemblies. The rooms were crowded with Indian youths and maidens. Parisian fashions have not invaded these villages – there were no crinolines – these are confined to the capital; but in their native garments there was no small variety – the many-coloured gowns of home manufacture – the richly embroidered kerchiefs of piña – earrings and necklaces, and other adornings; and then a vivacity strongly contrasted with the characteristic indolence of the Indian races. Tables were covered with refreshments – coffee, tea, wines, fruits, cakes and sweetmeats; and there seemed just as much of flirting and coquetry as ever marked the scenes of higher civilization. To the Europeans great attentions were paid, and their presence was deemed a great honour. Our young midshipmen were among the busiest and liveliest of the throng, and even made their way, without the aid of language, to the good graces of the Zagalas. Sampaloc, inhabited principally by Indians employed as washermen and women, is sometimes called the Pueblo de los Lavanderos. The festivities continued to the matinal hours.

In 1855 the Captain-General (Crespo) caused sundry statistical returns to be published, which throw much light upon the social condition of the Philippine Islands, and afford such valuable materials for comparison with the official data of other countries, that I shall extract from them various results which appear worthy of attention.

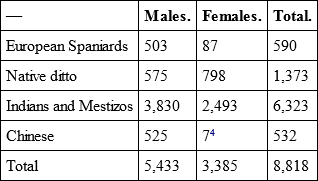

The city of Manila contains 11 churches, with 3 convents, 363 private houses; and the other edifices, amounting in all to 88, consist of public buildings and premises appropriated to various objects. Of the private houses, 57 are occupied by their owners, and 189 are let to private tenants, while 117 are rented for corporate or public purposes. The population of the city in 1855 was 8,618 souls, as follows: —

Примечание 14

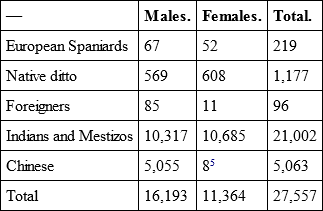

Far different are the proportions in another part of the capital, the Binondo district, on the other side of the river: —

Примечание 15

Of these, one male and two females (Indian) were more than 100 years old.

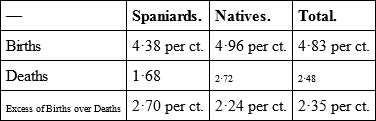

The proportion of births and deaths in Manila is thus given: —

In Binondo the returns are much less favourable: —

The statistical commissioners state these discrepancies to be inexplicable; but attribute it in part to the stationary character of the population of the city, and the many fluctuations which take place in the commercial movements of Binondo.

Binondo is really the most important and most opulent pueblo of the Philippines, and is the real commercial capital: two-thirds of the houses are substantially built of stone, brick and tiles, and about one-third are Indian wooden houses covered with the nipa palm. The place is full of business and activity. An average was lately taken of the carriages daily passing the principal thoroughfares. Over the Puente Grande (great bridge) their number was 1,256; through the largest square, Plaza de S. Gabriel, 979; and through the main street, 915. On the Calzada, which is the great promenade of the capital, 499 carriages were counted – these represent the aristocracy of Manila. There are eight public bridges, and a suspension bridge has lately been constructed as a private speculation, on which a fee is levied for all passengers.

Binondo has some tolerably good wharfage on the bank of the Pasig, and is well supplied with warehouses for foreign commerce. That for the reception of tobacco is very extensive, and the size of the edifice where the state cigars are manufactured may be judged of from the fact that nine thousand females are therein habitually employed.

The Puente Grande (which unites Manila with Binondo) was originally built of wood upon foundations of masonry, with seven arches of different sizes, at various distances. Two of the arches were destroyed by the earthquake of 1824, since which period it has been repaired and restored. It is 457 feet in length and 24 feet in width. The views on all sides from the bridge are fine, whether of the wharves, warehouses, and busy population on the right bank of the river, or the fortifications, churches, convents, and public walks on the left.

The population of Manila and its suburbs is about 150,000.

The tobacco manufactories of Manila, being the most remarkable of the “public shows,” have been frequently described. The chattering and bustling of the thousands of women, which the constantly exerted authority of the female superintendents wholly failed to control, would have been distracting enough from the manipulation of the tobacco leaf, even had their tongues been tied, but their tongues were not tied, and they filled the place with noise. This was strangely contrasted with the absolute silence which prevailed in the rooms solely occupied by men. Most of the girls, whose numbers fluctuate from eight to ten thousand, are unmarried, and many seemed to be only ten or eleven years old. Some of them inhabit pueblos at a considerable distance from Manila, and form quite a procession either in proceeding to or returning from their employment. As we passed through the different apartments specimens were given us of the results of their labours, and on leaving the establishment beautiful bouquets of flowers were placed in our hands. We were accompanied throughout by the superior officers of the administration, explaining to us all the details with the most perfect Castilian courtesy. Of the working people I do not believe one in a hundred understood Spanish.

The river Pasig is the principal channel of communication with the interior. It passes between the commercial districts and the fortress of Manila. Its average breadth is about 350 feet, and it is navigable for about ten miles, with various depths of from 3 to 25 feet. It is crossed by three bridges, one of which is a suspension bridge. The daily average movement of boats, barges, and rafts passing with cargo under the principal bridge, was 277, escorted by 487 men and 121 women (not including passengers). The whole number of vessels belonging to the Philippines was, in 1852 (the last return I possess), 4,053, representing 81,752 tons, and navigated by 30,485 seamen. Of these, 1,532 vessels, of 74,148 tons, having 17,133 seamen, belong to the province of Manila alone, representing three-eighths of the ships, seven-eighths of the tonnage, and seventeen-thirtieths of the mercantile marine. The value of the coasting trade in 1852 is stated to have been about four and a-half millions of dollars, half this value being in abacá (Manila hemp), sugar and rice being the next articles in importance. The province of Albay, the most southern of Luzon, is represented by the largest money value, being about one-fourth of the whole. On an average of five years, from 1850 to 1854, the coasting trade is stated to have been of the value of 4,156,459 dollars, but the returns are very imperfect, and do not include all the provinces. The statistical commission reports that on an examination of all the documents and facts accessible to them, in 1855, the coasting trade might be fairly estimated at 7,200,459 dollars.

At a distance of about three miles from Binondo, on the right bank of the Pasig, is the country house of the captain-general, where he is accustomed to pass some weeks of the most oppressive season of the year: it has a nice garden, a convenient moveable bath, which is lowered into the river, an aviary, and a small collection of quadrupeds, among which I made acquaintance with a chimpanzee, who, soon after, died of a pulmonary complaint.

CHAPTER II

VISIT TO LA LAGUNA AND TAYABAS

Having arranged for a visit to the Laguna and the surrounding hills, whose beautiful scenery has given to the island of Luzon a widely-spread celebrity, we started accompanied by the Alcalde Mayor, De la Herran, Colonel Trasierra, an aide-de-camp of the Governor, appointed to be my special guide and guardian, my kind friend and gentlemanly companion Captain Vansittart, and some other gentlemen. The inhabitants of the Laguna are called by the Indians of Manila Tagasilañgan, or Orientals. As we reached the various villages, the Principalia, or native authorities, came out to meet us, and musical bands escorted us into and out of all the pueblos. We found the Indian villages decorated with coloured flags and embroidered kerchiefs, and the firing of guns announced our arrival. The roads were prettily decorated with bamboos and flowers, and everything proclaimed a hearty, however simple welcome. The thick and many-tinted foliage of the mango – the tall bamboos shaking their feathery heads aloft – the cocoa-nut loftier still – the areca and the nipa palms – the plantains, whose huge green leaves give such richness to a tropical landscape – the bread-fruit, the papaya, and the bright-coloured wild-flowers, which stray at will over banks and branches – the river every now and then visible, with its canoes and cottages, and Indian men, women, and children scattered along its banks. Over an excellent road, we passed through Santa Ana to Taguig, where a bamboo bridge had been somewhat precipitately erected to facilitate our passage over the stream: the first carriage got over in safety; with the second the bridge broke down, and some delay was experienced in repairing the disaster, and enabling the other carriages to come forward. Taguig is a pretty village, with thermal baths, and about 4,000 inhabitants; its fish is said to be particularly fine. Near it is Pateros, which no doubt takes its name from the enormous quantity of artificially hatched ducks (patos) which are bred there, and which are seen in incredible numbers on the banks of the river. They are fed by small shell-fish found abundantly in the neighbouring lake, and which are brought in boats to the paterias on the banks of the Pasig. This duck-raising is called Itig by the Indians. Each pateria is separated from its neighbour by a bamboo enclosure on the river, and at sunset the ducks withdraw from the water to adjacent buildings, where they deposit their eggs during the night, and in the morning return in long procession to the river. The eggs being collected are placed in large receptacles containing warm paddy husks, which are kept at the same temperature; the whole is covered with cloth, and they are removed by their owners as fast as they are hatched. We saw hundreds of the ducklings running about in shallow bamboo baskets, waiting to be transferred to the banks of the river. The friar at Pasig came out from his convent to receive us. It is a populous pueblo, containing more than 22,000 souls. There is a school for Indian women. It has stone quarries worked for consumption in Manila, but the stone is soft and brittle. The neighbourhood is adorned with gardens. Our host the friar had prepared for us in the convent a collation, which was served with much neatness and attention, and with cordial hospitality. Having reached the limits of his alcadia, the kind magistrate and his attendants left us, and we entered a falua (felucca) provided for us by the Intendente de Marina, with a goodly number of rowers, and furnished with a carpet, cushions, curtains, and other comfortable appliances. In this we started for the Laguna, heralded by a band of musicians. The rowers stand erect, and at every stroke of the oar fling themselves back upon their seats; they thus give a great impulse to the boat; the exertion appears very laborious, yet their work was done with admirable good-humour, and when they were drenched with rain there was not a murmur. In the lake (which is called Bay) is an island, between which and the main land is a deep and dangerous channel named Quinabatasan, through which we passed. The stream rushes by with great rapidity, and vessels are often lost in the passage. The banks are covered with fine fruit trees, and the hills rise grandly on all sides. Our destination was Santa Cruz, and long before we arrived a pilot boat had been despatched in order to herald our coming. The sun had set, but we perceived, as we approached, that the streets were illuminated, and we heard the wonted Indian music in the distance. Reaching the river, we were conducted to a gaily-lighted and decorated raft, which landed us, – and a suite of carriages, in one of which was the Alcalde, who had come from his Cabacera, or head quarters, to take charge of us, – conducted the party to a handsome house belonging to an opulent Indian, where we found, in the course of preparation, a very handsome dinner or supper, and all the notables of the locality, the priest, as a matter of course, among them, assembled to welcome the strangers. We passed a theatre, which appeared hastily erected and grotesquely adorned, where, as we were informed, it was intended to exhibit an Indian play in the Tagál language, for our edification and amusement. I was too unwell to attend, but I heard there was much talk on the stage (unintelligible, of course, to our party), and brandishing of swords, and frowns and fierce fighting, and genii hunting women into wild forests, and kings and queens gaily dressed. The stage was open from the street to the multitude, of whom many thousands were reported to be present, showing great interest and excitement. I was told that some of the actors had been imported from Manila. The hospitality of our host was super-abundant, and his table crowded not only with native but with many European luxuries. He was dressed as an Indian, and exhibited his wardrobe with some pride. He himself served us at his own table, and looked and moved about as if he were greatly honoured by the service. His name, which I gratefully record, is Valentin Valenzuela, and his brother has reached the distinction of being an ordained priest.

Santa Cruz has a population of about 10,000 souls. Many of its inhabitants are said to be opulent. The church is handsome; the roads in the neighbourhood broad and in good repair. There is much game in the adjacent forests, but there is not much devotion to the chase. Almost every variety of tropical produce grows in the vicinity. Wild honey is collected by the natives of the interior, and stuffs of cotton and abacá are woven for domestic use. The house to which we were invited was well furnished, but with the usual adornings of saints’ images and vessels for holy water. In the evening the Tagála ladies of the town and neighbourhood were invited to a ball, and the day was closed with the accustomed light-heartedness and festivity: the bolero and the jota seemed the favourite attractions. Dance and music are the Indians’ delight, and very many of the evenings we passed in the Philippines were devoted to these enjoyments. Next morning the carriages of the Alcalde, drawn by the pretty little ponies of Luzon, conducted us to the casa real at Pagsanjan, the seat of the government, or Cabacera, of the province, where we met with the usual warm reception from our escort Señor Tafalla, the Alcalde. Pagsanjan has about 5,000 inhabitants, being less populous than Biñan and other pueblos in the province. Hospitality was here, as everywhere, the order of the day and of the night, all the more to be valued as there are no inns out of the capital, and no places of reception for travellers; but he who is recommended to the authorities and patronized by the friars will find nothing wanting for his accommodation and comfort, and will rather be surprised at the superfluities of good living than struck with the absence of anything necessary. I have been sometimes amazed when the stores of the convent furnished wines which had been kept from twenty to twenty-five years; and to say that the cigars and chocolate provided by the good friars would satisfy the most critical of critics, is only to do justice to the gifts and the givers.