полная версия

полная версияA Visit to the Philippine Islands

“For the administration of justice, the Philippines have one supreme and forty-two subordinate tribunals. The number is wholly insufficient for the necessities of 5,000,000 of inhabitants scattered over 1,200 islands, and occupying so vast a territorial space.” There can be no doubt that justice is often inaccessible, that it is costly, that it is delayed, defeated, and associated with many vexations. Spain has never been celebrated for the integrity of its judges, or the purity of its courts. A pleyto in the Peninsula is held to be as great a curse as a suit in Chancery in England, with the added evil of want of confidence in the administrators of the law. Their character would hardly be improved at a distance of 10,000 miles from the Peninsula; and if Spain has some difficulty in supplying herself at home with incorruptible functionaries, that difficulty would be augmented in her remotest possessions. There seemed to me much admirable machinery in the traditional and still existing usages and institutions of the natives. Much might, no doubt, be done to lessen the dilatory, costly and troublesome character of lawsuits, by introducing more of natural and less of technical proceedings; by facilitating the production and examination of evidence; by the suppression of the masses of papel sellado (documents upon stamped paper); by diminishing the cost and simplifying the process of appeal; and, above all, by the introduction of a code applicable to the ordinary circumstances of social life.

He thinks the attempts to conglomerate the population in towns and cities injurious to the agricultural interests of the country; but assuredly this agglomeration is friendly to civilization, good government and the production of wealth, and more likely than the dispersion of the inhabitants to provide for the introduction of those larger farms to which the Philippines must look for any very considerable augmentation of the produce of the land.

“The natural riches of the country are incalculable. There are immense tracts of the most feracious soil; brooks, streams, rivers, lakes, on all sides; mountains of minerals, metals, marbles in vast variety; forests whose woods are adapted to all the ordinary purposes of life; gums, roots, medicinals, dyes, fruits in great variety. In many of the islands the cost of a sufficiency of food for a family of five is only a cuarto, a little more than a farthing, a day. Some of the edible roots grow to an enormous size, weighing from 50 to 70 lbs.: – gutta-percha, caoutchouc, gum-lac, gamboge, and many other gums abound. Of fibres the number is boundless; in fact, the known and the unknown wealth of the islands only requires fit aptitudes for its enormous development.

“With a few legislative reforms,” he concludes, “with improved instruction of the clergy, the islands would become a paradise of inexhaustible riches, and of a well-being approachable in no other portion of the globe. The docility and intelligence of the natives, their imitative virtues (wanting though they be in forethought), make them incomparably superior to any Asiatic or African race subjected to European authority. Where deep thought and calculation are required, they will fail; but their natural dispositions and tendencies, and the present state of civilization among them, give every hope and encouragement for the future.”31

CHAPTER XXI

FINANCE, TAXATION, ETC

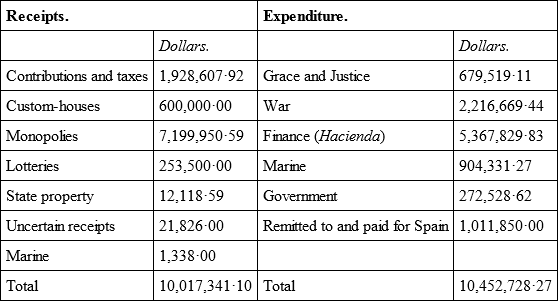

The gross revenues of the Philippines are about 10,000,000 dollars. The budget for 1859 is as follows: —

Thus about one-tenth of the gross revenue is received by the mother country in the following shapes: – Salaries of Spanish consuls in the East, 22,500 dollars; remittances to Spain and bills drawn by Spain, 680,600 dollars; tobacco and freights, 168,750 dollars; credits to French government for advances to the imperial navy, 140,000 dollars.

Of the direct taxes, 68,026·77 dollars are paid as tribute by the unconverted natives, 114,604·50 dollars by the mestizos (half-races), 136,208·78 dollars by the Chinese, and 1,609,757·87 dollars by the Indians (or tribes professing Christianity).

The produce of the customs is so small, and the expenses of collection so great – the cost of the coast and inland preventive service alone being 265,271·99 dollars; general and provincial administrations, between 70,000 and 80,000 dollars – that I am persuaded it would be a sound, wise and profitable policy to abandon this source of taxation altogether, and to declare all the ports of the Philippines free.

I have also come to the conclusion that the monopolies, which give a gross revenue to the treasury of more than 7,000,000 dollars, are, independently of their vicious and retardatory action upon the public weal, far less productive than taxation upon the same articles might be made by their emancipation from the bonds of monopoly. I leave here out of sight the enormous amount of fraud and crime, and the pernicious effects upon the public morals of a universal toleration of smuggling, as well as the consideration of all the vexations, delays, checks upon improvement, corruption of officials and the thousand inconveniences of fiscal interference at every stage and step; and only look at the acknowledged cost of the machinery – it amounts to about 5,000,000 dollars – so that the net produce to the State scarcely exceeds 2,000,000 dollars.

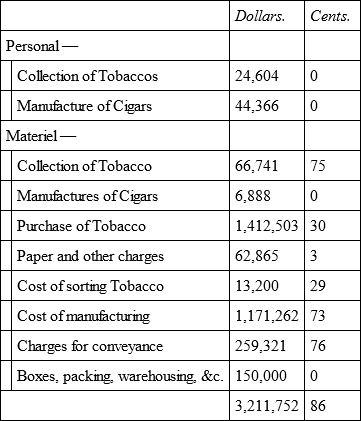

The whole receipt from the tobacco monopoly is 5,097,795 dollars. The expenses for which this department is debited are (independently of the proportion of the general charges of administration) —

So that the net rendering of this most valuable production is only 1,886,042·14 dollars, or 37 per cent. upon the gross amount, 63 per cent. being expended on the production of the tobacco and manufacture of the cigars. I am of opinion that from 4,000,000 to 5,000,000 dollars might be realized with immense benefit to the public by a tax upon cultivation, or the imposition of a simple export duty, or by a union of both. Production would thus be largely extended, prices moderated to the consumer and the net revenue probably more than doubled.

From the produce of the lottery, 253,500 dollars, there have to be deducted – expenses of administration, 4,472 dollars; prizes paid, 195,000 dollars; prizes not claimed, 1,000 dollars; commission on sales of tickets, 4,680 dollars; making in all, 205,152 dollars; so that this fertile source of misery, disappointment, and frequently of crime, does not produce a net income of 50,000 dollars to the State. It may well be doubted if such a source of revenue should be maintained. The revenue derived from cock-fights, 86,326·25 dollars, is to some extent subject to the same condemnation, as gambling is the foundation of both, but in the case of the galleras the produce is paid without deduction into the treasury.

In the Bisayas palm wine has been lately made the object of a State monopoly which produces 324,362 dollars, but is very vexatious in its operation and much complained of by the Indians. The tax on spirituous liquors gives 1,465,638 dollars. The opium monopoly brings 44,333·34 dollars; that of gunpowder, 21,406 dollars. Of smaller sources of income the most remarkable are – Papal bulls, giving 58,000 dollars; stamps, 39,600 dollars; fines, 30,550 dollars; post-office stamps, 19,490 dollars; fishery in Manila harbour, 6,500 dollars.

It is remarkable that there are no receipts from the sale or rental of lands. Public works, roads and bridges are in charge of the locality, while of the whole gross revenue more than seven-tenths are the produce of monopolies.

Of the government expenditure, under the head of Grace and Justice, the clergy receive 488,329·28 dollars, and for pious works 39,801·83; Jesuit missions to Mindanao, 25,000. The cost of the Audiencia is 65,556; of the alcaldes and gobernadores, 53,332 dollars.

In the war department the cost of the staff is 154,148·80 dollars; of the infantry, 857,031·17 dollars; cavalry, 52,901·73 dollars; artillery, 192,408·71 dollars; engineers, 32,173 dollars; rations, 140,644·31 dollars; matériel, 149,727·10 dollars; transport, 112,000 dollars; special services, 216,673·89 dollars. In the finance expenses the sum of 310,615·75 dollars appears as pensions.

The personnel of the marine department is 235,671·82 dollars; cost of building, repairing, &c., 266,813·17 dollars; salaries, &c., are 155,294·98 dollars; rations, 190,740·84 dollars.

The governor-general receives, including the secretariat, 31,056 dollars; expenses, 2,500 dollars. The heaviest charge in the section of civil services is 120,000 dollars for the mail steamers between Hong Kong and Manila, and 35,000 dollars for the service between Spain and Hong Kong. There is an additional charge for the post-office of 6,852 dollars. The only receipt reported on this account is for post-office stamps, 19,490 dollars.

I have made no reference to the minor details of the incomings and outgoings of Philippine finance. The mother country has little cause to complain, receiving as she does a net revenue of about 5s. per head from the Indian population. In fact, about half of the whole amount of direct taxation goes to Spain, independently of what Spanish subjects receive who are employed in the public service. The Philippines happily have no debt, and, considering that the Indian pays nothing for his lands, it cannot be said that he is heavily taxed. But that the revenues are susceptible of immense development – that production, agricultural and manufactured, is in a backward and unsatisfactory state – that trade and shipping might be enormously increased – and that great changes might be most beneficially introduced into many branches of administration, must be obvious to the political economist and the shrewd observer. The best evidence I can give of a grateful remembrance of the kindnesses I received will be the frank expression of opinions friendly to the progress and prosperity of these fertile and improveable regions. Meliorations many and great have already made their way; it suffices to look back upon the state of the Philippines, “cramped, cabined and confined” as they were, and to compare them with their present half-emancipated condition. No doubt Spain has much to learn at home before she can be expected to communicate commercial and political wisdom to her dependencies abroad. But she may be animated by the experience she has had, and at last discover that intercourse with opulent nations tends not to impoverish, but to enrich those who encourage and extend that intercourse.

CHAPTER XXII

TAXES

Down to the year 1784 so unproductive were the Philippines to the Spanish revenues, that the treasury deficit was supplied by an annual grant of 250,000 dollars provided by the Mexican government. A capitation tax was irregularly collected from the natives; also a custom-house duty (almojarifango) on the small trade which existed, and an excise (alcabala) on interior sales. Even to the beginning of the present century the Spanish American colonies furnished the funds for the military expenses of Manila. In 1829 the treasury became an independent branch of administration. Increase of tribute-paying population, the tobacco and wine monopoly, permission given to foreigners to establish themselves as merchants in the capital, demand for native and consumption of foreign productions, and a general tendency towards a more liberal policy, brought about their usual beneficial results; and, though slowly moving, the Philippines have entered upon a career of prosperity susceptible of an enormous extension.

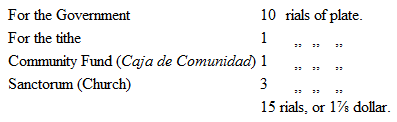

The capitation tax, or tribute paid by the natives, is the foundation of the financial system in the Philippines. It is the only direct tax (except for special cases), makes no distinction of persons and property, has the merit of antiquity, and is collected by a machinery provided by the Indians themselves. Originally it was levied in produce, but compounded for by the payment of a dollar (eight reales), raised afterwards to a dollar and a quarter, and finally the friars have managed to add to the amount an additional fifty per cent., of which four-fifths are for church, and one-fifth for commercial purposes.

The tribute is now due for every grown-up individual of a family, up to the age of sixty; the local authorities (cabezas de barangay), their wives and eldest or an adopted son, excepted. A cabeza is charged with the collection of the tribute of his cabaceria, consisting generally of about fifty persons. There are many other exceptions, such as discharged soldiers and persons claiming exemptions on particular grounds, to say nothing of the uncertain collections from Indians not congregated in towns or villages, and the certain non-collections from the wilder races. Buzeta estimates that only five per cent. of the whole population pay the tribute. Beyond the concentrated groups of natives there is little control; nor is the most extended of existing influences – the ecclesiastical – at all disposed to aid the revenue collector at the price of public discontent, especially if the claims of the convent are recognized and the wants of the church sufficiently provided for, which they seldom fail to be. The friar frequently stands between the fiscal authority and the Indian debtor, and, as his great object is to be popular with his flock, he, when his own expectations are satisfied, is naturally a feeble supporter of the tax collector. The friar has a large direct interest in the money tribute, both in the sanctorum and the tithe; but the Indian has many means of conciliating the padre and does not fail to employ them, and the padre’s influence is not only predominant, but it is perpetually present, and in constant activity. There is a decree of 1835 allowing the Indians to pay tribute in kind, but at rates so miserably low that I believe there is now scarcely an instance of other than metallic payments. The present amount levied is understood to be —

Which at 4s. 6d. per dollar makes a capitation tax of about 8s. 6d. per head.

The Sangleys (mestizos of Chinese origin) pay 20 rials government tribute, or 25 rials in all, being about 14s. sterling.

There are some special levies for local objects, but they are not heavy in amount.

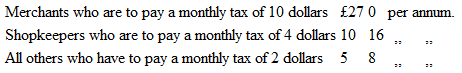

The Chinese have been particularly selected to be the victims of the tax-gatherer, and, considering the general lightness of taxation, and that the Chinese had been invited to the Philippines with every assurance of protection, and as a most important element for the development of the resources of the country, the decree of 1828 will appear tolerably exacting. It divides Chinese settlers into three classes: —

Not consenting to this, and if unmarried, they might quit the country in six months, or pay the value of their tribute in labour, and they were, after a delay of three months in the payment of the tax, to be fineable at 2 rials a day. At the time of issuing the decree there were 5,708 Chinese in the capital, of whom immediately 800 left for China, 1,083 fled to the mountains and were kindly received and protected by the natives, 453 were condemned to the public works, and the rest left in such a condition of discontent and misery that in 1831 the intendente made a strong representation to the government in their favour, and in 1834 authority was given to modify the whole fiscal legislation as regarded the Chinese.

The Chinese, on landing in Manila, whether as sailors or intending settlers, are compelled to inhabit a public establishment called the Alcaiceria de San Fernando, for which payment is exacted, and there is a revenue resulting to the State from the profits thereof.

CHAPTER XXIII

OPENING THE NEW PORTS OF ILOILO, SUAL AND ZAMBOANGA

The opening of the ports of Sual, Iloilo and Zamboanga to foreign trade, was of course intended to give development to the local interests of the northern, central and southern portions of the archipelago, the localities selected appearing to offer the greatest encouragements, and on the determination of the Spanish government being known, her Britannic Majesty’s Consul at Manila recommended the appointment of British vice-consuls at Sual and Iloilo, and certainly no better selections could have been made than were made on the occasion, for the most competent gentleman in each of the ports was fixed upon.

Mr. Farren’s report, which has been laid before Parliament, very fairly represents the claims of the new ports and their dependencies; each has its special recommendations. The population of the northern division, comprising Pangasinan, the two Ilocos (North and South), Abra and La Union, may be considered among the most industrious, opulent and intelligent of the Philippines. Cagayan produces the largest quantity of the finest quality of tobacco.

The central division, the most thickly peopled of the whole, has long furnished Manila with a large proportion of its exports, which, in progress of time, will, no doubt, be sent directly from the ports of production to those of consumption; while the southern, and the least promising at present, has every element which soil and climate can contribute to encourage the cultivation of vast tracts hitherto unreached by the civilizing powers of commerce and colonization.

The population in the northern division is large. In Ilocos, South and North, there are twelve towns with from 5,000 to 8,000 inhabitants; seven with 8,000 to 12,000; seven with from 12,000 to 20,000; and three with from 20,000 to 33,000. In Pangasinan, nine towns with from 5,000 to 12,000; seven with from 12,000 to 20,000; and three with from 20,000 to 26,000 inhabitants. The capital (Cabazera) of Cagayan has above 15,000 inhabitants. The middle zone presents a still greater number of populous places. Zebu has fourteen towns with 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants, and nine towns of from 10,000 to 12,000; and in Iloilo there are seven towns with from 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants; fourteen towns with from 10,000 to 20,000; seven with from 20,000 to 30,000; two with from 30,000 to 40,000; and one (Haro) with 46,000 inhabitants.

These statistics for 1857 show a great increase of population since Mr. Farren’s returns and prove that the removal of restrictions has acted most beneficially upon the common weal, imperfect as the emancipation has been. There cannot be a doubt that more expansive views would lead to the extension of a liberal policy, and that mines of unexplored and undeveloped treasure are to be found in the agricultural and commercial resources of these regions. The importance of direct intercourse with foreign countries is increased by the fact that, for many months of the year, the monsoons interrupt the communication of the remoter districts with the capital. The old spirit of monopoly not only denied to the producer the benefit of high prices, and to the consumer the advantage of low prices, but the trade itself necessarily fell into the hands of unenterprising and sluggish merchants, wholly wanting in that spirit of enterprise which is the primum mobile of commercial prosperity. For it is the condition, curse and condemnation of monopoly, that while it narrows the vision and cramps the intellect of the monopolist, it delivers the great interests of commerce to the guardianship of an inferior race of traders, excluding those higher qualities which are associated with commercial enterprise when launched upon the wide ocean of adventurous and persevering energy. How is the tree to reach its full growth and expansion whose branches are continually lopped off lest their shadows should extend, and their fruit fall for the benefit of others than its owner?

But in reference to the beneficial changes which have been introduced, their value has been greatly diminished by the imperfect character of the concessions. They should have been complete; they should, while opening the ports to foreign trade, have allowed that trade full scope and liberty. The discussions which have taken place have, however, been eminently useful, and the part taken in favour of commercial freedom by Mr. Bosch and Mr. Loney, both British vice-consuls, has been creditable to their zeal and ability. In the Philippines, the tendency of public opinion is decidedly in the right direction. The resistance which for so many years, or even centuries, opposed the admission of strangers to colonial ports, no doubt was grounded upon the theory that they would bring less of trade than they would carry away – that they would participate in the large profits of those who held the monopoly, but not confer upon them any corresponding or countervailing advantages.

Mr. Farren states that, in 1855, “the British trade with the Philippines exceeded in value that of Great Britain with several of the States of Europe, with that of any one State or port in Africa, was greater than the British trade with Mexico, Columbia, or Guatemala, and nearly ranked in the second-class division of the national trade with Asia, the total value of exports and imports approaching three millions sterling. The export of sugar to Great Britain and her colonies was, in 1854, 42,400 tons, that to Great Britain alone having gradually grown upon the exports of 1852, which was 5,061 tons, to 27,254 tons, which exceeds the exports to the whole world in 1852. The imports of British goods and manufactures, which was 427,020l. in value in 1845, exceeded 1,000,000l. sterling in 1853.” It still progresses, and the removal of any one restriction, the encouragement of any one capability, will add to that progress, and infallibly augment the general prosperity.

The statistics of the island of Panay for 1857 give to the province of Iloilo 527,970; to that of Capiz, 143,713; and to that of Antique, 77,639; making in all 749,322, or nearly three-quarters of a million of inhabitants. The low lands of Capiz are subject to frequent inundations. It has a fine river, whose navigation is interfered with by a sandbank at its mouth. The province is productive, and gives two crops of rice in the year. The harbours of Batan and of Capiz (the cabacera) are safe for vessels of moderate size. The inhabitants of Antique, which occupies all the western coast of Panay, are the least industrious of the population of the island. The coast is dangerous. It has two pueblos, Bugason and Pandan, with more than 10,000 souls. The cabacera San José has less than half that number. The roads of the provinces are bad and communications with Iloilo difficult. The lands are naturally fertile, but have not been turned to much account by the Indians. There are only forty-two mestizos in the province. There is a small pearl and turtle fishery, and some seaslugs are caught for the Chinese market.

Iloilo has, no doubt, been fixed on as the seat of the government, from the facilities it offers to navigation; but it is much smaller, less opulent and even less active than many of the towns in its neighbourhood. The province of Iloilo is, on the whole, perhaps the most advanced of any in the Philippines, excepting the immediate neighbourhood of the capital. It has fine mountainous scenery, richly adorned with forest trees, while the plains are eminently fertile. All tropical produce appears to flourish. The manufacturing industry of the women is characteristic, and has been referred to in other places, especially with reference to the extreme beauty of the piña fabric. Of the mode of preparing the fabric Mallat gives this account: —

“It is from the leaves of the pine-apple – the plant which produces such excellent fruits – that the white and delicate threads are drawn which are the raw material of the nipis or piña stuffs. The sprouts of ananas are planted, which sometimes grow under the fruit to the number of a dozen; they are torn off, and are set in a light soil, sheltered, if possible, and they are watered as soon as planted. After four months the crown is removed, in order to prevent the fruiting, and that the leaves may grow broader and longer. At the age of eight months they are an ell in length, and six fingers in breadth, when they are torn away and stretched out on a plank, and, while held by his foot, the Indian with a piece of broken earthenware scrapes the pulp till the fibres appear. These are taken by the middle, and cautiously raised from one end to the other; they are washed twice or thrice in water, dried in the air and cleaned; they are afterwards assorted according to their lengths and qualities. Women tie the separate threads together in packets, and they are ready for the weaver’s use. In the weaving it is desirable to avoid either too high or too low a temperature – too much drought, or too much humidity – and the most delicate tissues are woven under the protection of a mosquito net. Such is the patience of the weaver, that she sometimes produces not more than half an inch of cloth in a day. The finest are called pinilian, and are only made to order. Ananas are cultivated solely for the sake of the fibre, which is sold in the market. Most of the stuffs are very narrow; when figured with silk, they sell for about 10s. per yard. The plain, intended for embroidery, go to Manila, where the most extravagant prices are paid for the finished work.”