полная версия

полная версияA Visit to the Philippine Islands

That such large portions of the islands should be held by independent tribes, whether heathen or Mahomedan, is not to be wondered at when the geographical character of the country is considered. Many of their retreats are inaccessible to beasts of burden; the valleys are intolerably hot; the mountains unsheltered and cold. There is also much ignorance as to the localities, and the Spaniards are subject to be surprised from unknown ambushes in passes and ravines. The forests, through which the natives glide like rabbits, are often impenetrable to Europeans. No attempts have succeeded in enticing the “idolaters” down to the plains from these woods and mountains, to be tutored, taxed and tormented. Yet it is a subject of complaint that these barbarians interfere, as no doubt they do, with the royal monopoly of tobacco, which they manage to smuggle into the provinces. “Fiscal officers and troops,” says De Mas, “are stationed to prevent these abuses, but these protectors practise so many extortions on the Indians, and cause so much of discontent, that commissions of inquiry become needful, and the difficulties remain unsolved.” In some places the idolaters molest “the peaceful Christian population,” and make the roads dangerous to travellers. De Mas has gathered information from various sources, and from him I shall select a few particulars; but it appears to me there is too much generalization as to the unsubjugated tribes, who are to be found in various stages of civilization and barbarism. The Tinguianes of Ilocos cultivate extensive rice-fields, have large herds of cattle and horses, and carry on a considerable trade with the adjacent Christian population. The Chinese type is said to be traceable in this race. The women wear a number of bracelets, covering the arm from the wrist to the elbow. The heaviest Tinguian curse is, “May you die while asleep,” which is equivalent to saying, “May your death-bed be uncelebrated.” It is a term of contempt for an Indian to say to another, “Malubha ang Caitiman mo” – Great is thy blackness (negregura, Sp.). The Indians call Africans Pogot.

There are many Albinos in the Philippines. They are called by the natives Sons of the Sun; some are white, some are spotted, and others have stripes on their skins. They are generally of small intellectual capacity.

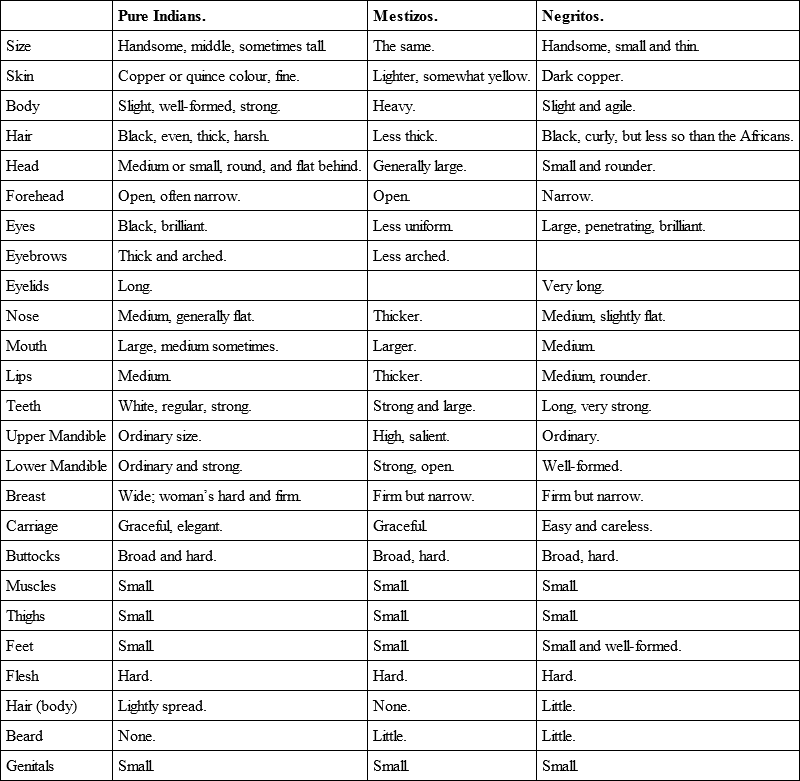

Buzeta gives the following ethnological table, descriptive of the physical characteristics of the various races of the Philippines: —

The Altaban Indians have an idol whom they call Cubiga, whose wife is Bujas. The Gaddans give the name of Amanolay, meaning Creator of Man, to the object of their worship, and his goddess is Dalingay. There are no temples nor public rites, but appeals to the superior spirits in cases of urgency are generally directed by the female priest or sorceress, who sprinkles the idol with the blood of a buffalo, fowl or guinea-pig, offers libations, while the Indians lift up their hands exclaiming, “Siggam Cabunian! Siggam Bulamaiag! Siggam aggen!” (O thou God! O thou beautiful moon! O thou star!) A brush is then dipped in palm wine, which is sprinkled over the attendants. (This is surely an imitation of Catholic aspersions.) A general carousing follows.

The priests give many examples of what they call Indian ignorance and stupidity, but these examples generally amount only to a disclaimer of all knowledge respecting the mysteries of creation, the origin and future destiny of man, the nature of religious obligations, and the dogmas of the Catholic faith. It may be doubted whether the mere habitual repetition of certain formulas affords more satisfactory evidence of Christian advancement than the openly avowed ignorance of these heathen races.

If an Indian is murdered by one of a neighbouring tribe, and the offence not condoned by some arranged payment, it is deemed an obligation on the part of the injured to retaliate by killing one of the offending tribe.

The popular amusement is dancing; they form themselves into a circle, stretching out their hands, using their feet alternately, leaping on one and lifting the other behind; so they move round and round with loud cries to the sounds of cylindrical drums struck by both hands.

The skulls of animals are frequently used for the decoration of the houses of the Indians. Galvey says he counted in one dwelling, in Capangar, 405 heads of buffaloes and bullocks, and more than a thousand of pigs, causing an intolerable stench.

They use the bark of the Uplay in cases of intermittent fever, and have much knowledge of the curative qualities of certain herbs; they apply hot iron to counteract severe local pain, so that the flesh becomes cauterized; but they almost invariably have recourse to amulets or charms, and sacrifice fowls and animals, which are distributed among the attendants on the sick persons.

Padre Mozo says of the Italons (Luzon) that he has seen them, after murdering an enemy, drink his blood, cut up the lungs, the back of the head, the entrails, and other parts of the body, which they eat raw, avowing that it gave them courage and spirit in war. The skulls are kept in their houses to be exhibited on great occasions. This custom is probably of Bornean origin, for Father Quarteron, the vicar apostolic of that island, told me that he once fell in with a large number of savages who were carrying in procession the human skulls with which their houses were generally adorned, and which they called “giving an airing to their enemies.” The teeth are inserted in the handles of their hangers. After enumerating many more of the barbarous customs of the islands, the good friar Mozo exclaims: – “Fancy our troubles and labours in rescuing such barbarians from the power of the devil!” They sacrifice as many victims as they find fingers opened after death. If the hand be closed, none. They suffer much from cutaneous diseases. The Busaos paint their arms with flowers, and to carry ornaments bore their ears, which are sometimes stretched down to their shoulders. The Ifugaos wear on a necklace pieces of cane denoting the number of enemies they have killed. Galvey says he counted twenty-three worn by one man who fell in an affray with Spanish troops. This tribe frequently attacks travellers in the mountains for the sake of their skulls. The missionaries represent them as the fiercest enemies of Christians. Some of the monks speak of horrible confessions made by Igorrote women after their conversion to Christianity, of their intercourse with monkeys in the woods, and the Padre Lorenzo indulges in long details on the subject, declaring, moreover, that a creature was once brought to him for baptism which “filled him with suspicion.” De Mas reports that a child with long arms, covered with soft hair, and much resembling a monkey, was exhibited by his mother in Viyan, and taught to ask for alms.

De Mas recommends that the Spanish Government should buy the saleable portion of the Mahomedan and pagan tribes, convert them, and employ them in the cultivation of land; and he gives statistics to show that there would be an accumulation of 120 per cent., while their removal would set the Indians together by the ears, who would destroy one another, and relieve the islands from the plague of their presence. This would seem a new chapter in the history of slave-trade experiments. He calculates that there are more than a million pagans and Mahomedans in the islands. Galvey’s “Diary of an Expedition to Benguet in January, 1829,” and another to Bacun in December, 1831, are histories of personal adventures, many of a perilous character, in which many lives were lost, and many habitations destroyed. They are interesting as exhibiting the difficulties of subjugating these mountain races. Galvey conducted several other expeditions, and died in 1839.

There are few facts of more interest, in connection with the changes that are going on in the Oriental world, than the outpouring of the surplus Chinese population into almost every region eastwards of Bengal; and in Calcutta itself there is now a considerable body of Chinese, mostly shoemakers, many of whom have acquired considerable wealth, and they are banded together in that strong gregarious bond of nationality which accompanies them wherever they go, and which is not broken, scarcely even influenced, by the circumstances that surround them. In the islands of the Philippines they have obtained almost a monopoly of the retail trade, and the indolent habits of the natives cannot at all compete with these industrious, frugal, and persevering intruders. Hence they are objects of great dislike to the natives; but, as their generally peaceful demeanour and obedience to the laws give no hold to their enemies, their numbers, their wealth, their importance increase from year to year. Yet they are but birds of passage, who return home to be succeeded by others of their race. They never bring their wives, but take to themselves wives or hand-maidens from the native tribes. Legitimate marriage, however, necessitates the profession of Christianity, and many of them care little for the public avowal of subjection to the Church of Rome. They are allowed no temple to celebrate Buddhist rites, but have cemeteries specially appropriated to them. They pay a fixed contribution, which is regulated by the rank they hold as merchants, traders, shopkeepers, artisans, servants, &c. Whole streets in Manila are occupied by them, and wherever we went we found them the most laborious, the most prosperous of the working classes. Thousands upon thousands of Chinamen arrive, and are scattered over the islands, but not a single Chinese woman accompanies them from their native country.

In the year 1857, 4,232 Chinamen landed in the port of Manila alone, and 2,592 left for China.

Of the extraordinary unwillingness of the women of China to emigrate, no more remarkable evidence can be found than in the statistics of the capital of the Philippines. In 1855, there were in the fortress of Manila 525 Chinamen, but of females only two women and five children. In Binondo, 5,055 Chinamen, but of females only eight, all of whom were children. Now, when it is remembered that the Philippines are, with a favourable monsoon, not more than three or four days’ sail from China, that there are abundance of opulent Chinese settled in the island, that the desire of having children and perpetuating a race is universal among the Chinese people, it may be easily conceived that there must be an intensely popular feeling opposed to the emigration of women.

And such is undoubtedly the fact, and it is a fact which must prove a great barrier to successful coolie emigration. No women have been obtainable either for the British or Spanish colonies, though the exportation of coolies had exceeded 60,000, and except by kidnapping and direct purchase from the procuresses or the brothels, it is certain no woman can be induced to emigrate. This certainty ought to be seriously weighed by the advocates of the importation of Chinese labourers into the colonies of Great Britain. In process of time, Hong Kong will probably furnish some voluntary female emigrants, and the late legalization of emigration by the Canton authorities will accelerate the advent of a result so desirable.

During five years, ending in 1855, there were for grave crimes only fourteen committals of Chinamen in the whole of the provinces, being an average of less than three per annum; no case of murder, none of robbery with violence, none for rape. There were nine cases of larceny, two of cattle-stealing, one forgery, one coining, one incendiarism. These facts are greatly creditable to the morality of the Chinese settlers. Petty offences are punished, as in the case of the Indians, by their own local principalia.

A great majority of the shoemakers in the Philippines are Chinese. Of 784 in the capital, 633 are Chinamen, and 151 natives. Great numbers are carpenters, blacksmiths, water-carriers, cooks, and daily labourers, but a retail shopkeeping trade is the favourite pursuit. Of late, however, many are merging into the rank of wholesale dealers and merchants, exporting and importing large quantities of goods on their own account, and having their subordinate agents scattered over most of the islands. Where will not a Chinaman penetrate – what risks will he not run – to what suffering will he not submit – what enterprises will he not engage in – what perseverance will he not display – if money is to be made? And, in truth, this constitutes his value as a settler: he is economical, patient, persistent, cunning; submissive to the laws, respectful to authority, and seeking only freedom from molestation while he adds dollar to dollar, and when the pile is sufficient for his wants or his ambition, he returns home, to be succeeded by others, exhibiting the same qualities, and in their turn to be rewarded by the same success.

When encouragement was first given to the Chinese to settle in the Philippines, it was as agricultural labourers, and they were not allowed to exercise any other calling. The Japanese were also invited, of whom scarcely any are now to be found in the islands. The reputation of the Chinese as cultivators of the land no doubt directed the attention of the Manila authorities towards them; but no Chinaman continues in any career if he can discover another more profitable. Besides this, they were no favourites among the rural population, and in their gregarious nature were far more willing to band themselves together in groups and hwey (associations) than to disperse themselves among the pastoral and agricultural races, who were jealous of them as rivals and hated them as heathens. They have created for themselves a position in the towns, and are now too numerous and too wealthy to be disregarded or seriously oppressed. They are mostly from the province of Fokien, and Amoy is the principal port of their embarkation. I did not find among them a single individual who spoke the classical language of China, though a large proportion read the Chinese character.

When a Chinese is examined on oath, the formula of cutting off the head of a white cock is performed by the witness, who is told that, if he do not utter the truth, the blood of his family will, like that of the cock, be spilt and perdition overtake them. My long experience of the Chinese compels me to say that I believe no oath whatever – nothing but the apprehension of punishment – affords any, the least security against perjury. In our courts in China various forms have at different times been used – cock beheading; the breaking of a piece of pottery; the witness repeating imprecations on himself, and inviting the breaking up of all his felicities if he lied; the burning of a piece of paper inscribed with a form of oath, and an engagement to be consumed in hell, as that paper on earth, if he spoke not the truth; – these and other ceremonies have utterly failed in obtaining any security for veracity. While I was governor of Hong Kong an ordinance was passed abolishing the oath-taking, as regards the Chinese, and punishing them severely as perjurers when they gave false testimony. The experiment has succeeded in greatly fortifying and encouraging the utterance of truth and in checking obscurity and mendacity. I inquired once of an influential person in Canton what were the ceremonies employed among themselves where they sought security for truthful evidence. He said there was one temple in which a promise made would be held more binding than if made in any other locality; but he acknowledged their tribunals had no real security for veracity. There is a Chinese proverb which says, “Puh tah, puh chaou,” meaning “Without blows, no truth;” and the torture is constantly applied to witnesses in judicial cases. The Chinese religiously respect their written, and generally their ceremonial, engagements – they “lose face” if these are dishonoured. But little disgrace attends lying, especially when undetected and unpunished, and the art of lying is one of the best understood arts of government. Lies to deceive barbarians are even recommended and encouraged in some of their classical books.

CHAPTER IX

ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE

The supreme court of justice in the Philippines is the Audiencia established in Manila, which is the tribunal of appeal from the subordinate jurisdiction, and the consultative council of the Governor-General in cases of gravity.

The court is composed of seven oidores, or judges. The president takes the title of Regent. There are two government advocates, one for criminal, the other for civil causes, and a variety of subordinate officers. There are no less than eighty barristers, matriculated to practise in the Audiencia.

A Tribunal de Comercio, presided over by a judge nominated by the authorities, and assisted, under the title of Consules, by gentlemen selected from the principal mercantile establishments of the capital, is charged with the settlement of commercial disputes. There is a right of appeal to the Audiencia, but scarcely any instance of its being exercised.

There is a censorship called the Comercia permanente de censura. It consists of four ecclesiastics and four civilians, presided over by the civil fiscal, and its authority extends to all books imported into or printed in the islands.

There are fourscore lawyers (abogados) in Manila. As far as my experience goes, lawyers are the curse of colonies. I remember one of the most intelligent of the Chinese merchants who had settled at Singapore, after having been long established at Hong Kong, telling me that all the disadvantages of Singapore were more than compensated by the absence of “the profession,” and all the recommendations of Hong Kong more than counterbalanced by the presence of gentlemen occupied in fomenting, and recompensed for fomenting, litigations and quarrels. Many of them make large fortunes, not unfrequently at the expense of substantial justice. A sound observer says, that in the Philippines truth is swamped by the superfluity of law documents. The doors opened for the protection of innocence are made entrances for chicanery, and discussions are carried on without any regard to the decorum which prevails in European courts. Violent invectives, recriminations, personalities, and calumnies, are ventured upon under the protection of professional privilege. When I compare the equitable, prompt, sensible and inexpensive judgments of the consular courts in China with the results of the costly, tardy, unsatisfactory technicalities of judicial proceedings in many colonies, I would desire a general proviso that no tribunal should be accessible in civil cases until after an examination by a court of conciliation. The extortions to which the Chinese are subjected, in Hong Kong, for example – and I speak from personal knowledge – make one blush for “the squeezing” to which, indeed, the corruption of their own mandarins have but too much accustomed them. In the Philippines there is a great mass of unwritten, or at least unprinted, law, emanating from different and independent sources, often contradictory, introduced traditionally, quoted erroneously; a farrago, in which the “Leyes de Indias,” the “Siete partidas,” the “Novisima recompilacion,” the Roman code, the ancient and the royal fueros – to say nothing of proclamations, decrees, notifications, orders, bandos – produce all the “toil and trouble” of the witches’ cauldron, stirred by the evil genii of discord and disputation.

Games of chance (juegos de azar) are strictly prohibited in the Philippines, but the prohibition is utterly inefficient; and, as I have mentioned before, the Manila papers are crowded with lists of persons fined or imprisoned for violation of the law; sometimes forty or fifty are cited in a single newspaper. More than one captain-general has informed me that the severity of the penalty has not checked the universality of the offence, connived at and participated in by both ecclesiastics and civilians.

The fines are fifty dollars for the first, and one hundred dollars for the second, offence, and for the third, the punishment which attaches to vagabondage – imprisonment and the chain-gang.

Billiard-tables pay a tax of six dollars per month. There is an inferior wooden table which pays half that sum.

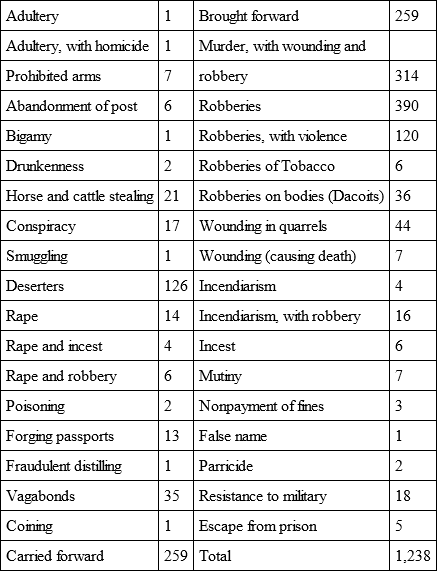

The criminal statistics of five years, from 1851 to 1855 present the following total number of convictions for the graver offences. They comprise the returns from all the provinces. Of the whole number of criminals, more than one-half are from 20 to 29 years old; one-third from 30 to 39; one-ninth from 40 to 49; one-twentieth from 15 to 19; and one-forty-fifth above 50.

They consist of 467 married, 81 widowers, and 690 unmarried men.

During the said period 236 had completed the terms of their sentences, 217 had died, and 785 remained at the date of the returns.

In the city of Manila there was only one conviction for murder in five years. The proportion of the graver offences in the different provinces is nearly the same, except in the island of Negros, where of forty-four criminals, twenty-eight were convicted of murder.

CHAPTER X

ARMY AND NAVY

The army of the Philippines, with the exception of two brigades of artillery and a corps of engineers which are furnished by Spain, is recruited from the Indians, and presents an appearance generally satisfactory. They are wholly officered by Europeans.

There are nine regiments of native infantry, one of cavalry, called the Luzon Lancers, and there is a reserve corps of officers called Cuadro de Remplazos, from whom individuals are selected to fill up vacancies.

There is a small body of Alabarderos de servicio at the palace in the special service of the captain-general. Their origin dates from A.D. 1590, and their halberds and costume add to the picturesque character of the palace and the receptions there.

There are also four companies called the Urban Militia of Manila, composed of Spaniards, who may be called upon by the governor for special services or in cases of emergency.

A medical board exercises a general inspection over the troops. Its superior functionaries are European Spaniards. Hospitals in which the military invalids are received are subject to the authority of the medical board as far as the treatment of such invalids is concerned. The medical board nominates an officer to each of the regiments, who is called an Ayudante.

Of late a considerable body of native troops has been sent from Manila to Cochin China, in order to co-operate with the French military and marine forces in that country. They are reported to have behaved well in a service which can have had few attractions, and in which they have been exposed to many sufferings, in consequence of the climate and the hostile attitude of the native inhabitants. What object the Spaniards had in taking so important a part in this expedition to Touron remains hitherto unexplained. Territory and harbours in Oriental regions, rich and abundant, they hold in superfluity; and assuredly Cochin China affords nothing very inviting to well-informed ambition; nor are the Philippines in a condition to sacrifice their population to distant, uncertain, perilous, and costly adventures. There is no national pride to be flattered by Annamite conquests, and the murder of a Spanish bishop may be considered as atoned for by the destruction of the forts and scattering of the people, at the price, however, of the lives of hundreds of Christians and of a heavy pecuniary outlay. France has its purposes – frankly enough disclosed – to obtain some port, some possession of her own, in or near the China seas. I do not think such a step warrants distrust or jealousy on our part. The question may be asked, whether the experiment is worth the cost? Probably not, for France has scarcely any commercial interest in China or the neighbouring countries; nor is her colonial system, fettered as it always has been by protections and prohibitions, likely to create such interest. In the remote East, France can carry on no successful rivalry with Great Britain, the United States, Holland, or Spain, each of which has points of geographical superiority and influence which to France are not accessible. One condition is a sine quâ non in these days of trading rivalry – lowness of price, associated with cheapness of transport. France offers neither to the foreign consumer in any of the great articles of supply: she will have high prices for her producers.