полная версия

полная версияThe Memoirs of Admiral Lord Beresford

The men were classed in the following categories, each "part of the ship" being divided into port watch and starboard watch.

The Forecastlemen

The Foretopmen

The Maintopmen

The Mizentopmen

The Gunners

The Afterguard

The Royal Marines

The Idlers

The Forecastlemen were most experienced seamen. They wore their caps a little differently from the others. They manned the foreyard, and worked the foresail, staysail, jib, flying jib, jibboom, flying jibboom and lower studdingsails.

The Foretopmen worked the foretopsail, foretopgallant and foreroyal yards, foretopgallantmast, foretopmast and topgallant studding-sails.

The Maintopmen worked the maintopsail, maintopgallant and main-royal yards and maintopgallantmast, maintopmast and topgallant studding-sails.

The Mizentopmen worked the mizentopsail, mizentopgallant and mizen-royal yards, and mizentopgallantmast, mizentopmast and mizencourse (if there was one), also the driver.

The upper-yard men were the smartest in the ship, whose character largely depended upon them.

The Gunners, assisted by the Afterguard, worked the mainsail and mainyard. These were generally old and steady men, who were not very quick aloft. The gunners were also responsible for the care and maintenance of the gun gear, side tackles, train tackles and the ammunition. The senior warrant officer was the gunner.

There were only three warrant officers: – gunner, boatswain and carpenter.

The Royal Marines were divided between fore and aft, working on forecastle and quarterdeck. I remember seeing a detachment of Marines, upon coming aboard, fallen in while the blacksmith, lifting up each man's foot behind him, wrenched off and dropped into a bucket the metal on the heel of his boot, lest it should mark the deck.

The Afterguard worked on the quarterdeck and helped with the mainyard. They were the less efficient men and were therefore employed under the eye of the commander.

The Idlers were not idlers. They were so called because (theoretically) they had their nights in, although actually they turned out at four o'clock a.m. They were artificers, such as carpenters, caulkers, plumbers, blacksmiths, etc. They worked all day at their several trades until their supper-time. They were nearly all old petty officers, steady and respectable. It was part of their duty to man the pumps every morning for washing decks. I made up my mind that, if ever I was in a position to do so, I would relieve them of an irksome and an inappropriate duty.

In action, the carpenters worked below decks, stopping holes with shot-plugs, while many of the other Idlers worked in the magazines. Among the Idlers was the ship's musician – unless the ship carried a band – who was a fiddler. He used to play to the men on the forecastle after working hours and when they manned the capstan. Personally I always considered the name of Idlers to be anomalous. They are now called Daymen.

Among the ship's company were several negroes. At that time, it was often the case that the captain of the hold and the cooper were coloured men.

An instance of the rapidity and efficiency of the organisation of the Marlborough occurred upon the night before she sailed for the Mediterranean. She was newly commissioned, and she carried a large number of supernumeraries on passage. We took out 1500 all told. A fire broke out on the orlop deck; the drum beat to quarters; every man instantly went to his station, to which he had previously been told off; and the fire was speedily extinguished. The event was my first experience of discipline in a big ship.

The nature of the discipline which was then in force, I learned on the way out to the Mediterranean. In the modern sense of the word, discipline was exemplified by the Royal Marines alone. I cannot better convey an idea of the old system than by means of an illustration. Supposing that a Marine and a bluejacket had each committed an offence. The Marine was brought up on the quarter-deck before the commander, and the charge was read to him. The commander asked him what he had to say. The prisoner, standing rigidly to attention, embarked upon a long rambling explanation. If his defence were invalid, the commander cut him short, and the sergeant gave his order. "Right turn. Quick march." The Marine, although continuing to protest, obeyed automatically, and away he went. He continued to talk until he was out of hearing, but he went. Not so the bluejacket. He did not stand to attention, not he. He shifted from one foot to the other, he hitched his breeches, fiddled with his cap, scratched his head.

"Well, sir," said he, "it was like this here, sir," … and he began to spin an interminable yarn.

"That'll do, my man," quoth the commander. But, not at all. "No, sir, look here, sir, what I wants to say is this" – and so on, until the commander had to order a file of Marines to march him below.

But both Marine and bluejacket had this in common: each would ask the commander to settle the matter rather than let it go before the captain; and the captain, to sentence him rather than hold a court-martial.

The explanation of the difference between the old system of discipline and the new is that in the sailing days it was of the first importance that the seaman should be capable of instant independent action. The soldier's uniformity and military precision were wholly unsuited to the sailor, who, at any moment, might have to tackle an emergency on his own initiative. If a seaman of the old days noticed anything wrong aloft, up he would run to put it right, without waiting for orders. Life and death often hung upon his promptitude of resource.

In the old days, we would often overhear such a conversation as the following: —

Officer: "Why the blank dash didn't you blank well do so-and-so when I told you?"

Man: "Why didn't I? Because if I had I should have been blank well killed and so would you."

Officer: "Damn you, sir, don't you answer me! I shall put you in the report."

Man: "Put me in the ruddy report, then."

And the next day the commander, having heard both sides, would say to the officer,

"Why, the man was quite right." And to the man, "You had no right to argue with the officer. Don't do it again. Now get away with you to hell."

And everyone would part the best of friends.

The change came with the improvement and progress in gunnery, which involved, first, the better drilling of the small-arm companies. In my early days, the small-arm companies used to drill with bare feet. Indeed, boots were never worn on board. It was of course impossible to wear boots going aloft for a sailor going aloft in boots would injure the heads and hands of his topmates. Occasionally the midshipmen went aloft barefooted like the men. So indurated did the feet of the sailors become, that they were unable to wear boots without discomfort, and often carried them when they were ashore.

A sailor's offences were hardly ever crimes against honour. They rather arose from the character induced by his calling. Its conditions were hard, dangerous and often intensely exciting. The sailor's view was devil-may-care. He was free with his language, handy with his fists and afraid of nothing. A smart man might receive four dozen for some violence, and be rated petty officer six months afterwards. Condemnation was then the rule. Personally, I endeavoured to substitute for it, commendation. For if there are two men, one of whom takes a pride in (say) keeping his rifle clean, and the other neglects it, to ignore the efficiency of the one is both to discourage him and to encourage the other.

Before the system of silence was introduced by the Marlborough the tumult on deck during an evolution or exercise was tremendous. The shouting in the ships in Malta Harbour could be heard all over Valetta. The Marlborough introduced the "Still" bugle-call. At the bugle-call "Still" every man stood motionless and looked at the officer. For in order to have an order understood, the men must be looking at the officer who gives it. During the Soudan war, I used the "Still" at several critical moments. Silence and attention are the first necessities for discipline. About this time the bugle superseded the drum in many ships for routine orders.

There were few punishments, the chief punishment being the cat. The first time I saw the cat applied, I fainted. But men were constantly being flogged. I have seen six men flogged in one morning. Even upon these painful occasions, the crew were not fallen in. They were merely summoned aft "for punishment" – "clear lower deck lay aft for punishment" was piped – and grouped themselves as they would, sitting in the boats and standing about, nor did they even keep silence while the flogging was being inflicted. The officers stood within three sides of a square formed by the Marines. Another punishment was "putting the admiral in his barge and the general in his helmet," when one man was stood in a bucket and the other had a bucket on his head.

Very great credit is due to Admiral Sir William Martin, who reformed the discipline of the Fleet. The Naval Discipline Act was passed in 1861; the New Naval Discipline Act in 1866. In 1871 a circular was issued restricting the infliction of corporal punishment in peace time. Flogging was virtually abolished in 1879. (Laird Clowes' The Royal Navy, vol. 7.) Now we have proper discipline and no cat. In former days, we had the cat but no proper discipline.

The men were granted very little leave. They were often on board for months together. When they went ashore, there they remained until they had spent their last penny; and when they came on board they were either drunk or shamming drunk. For drunkenness was the fashion then, just as sobriety is, happily, the fashion now. In order to be in the mode, a man would actually feign drunkenness on coming aboard. In many a night-watch after leave had been given have I superintended the hoisting in of drunken men, who were handed over to the care of their messmates. To-day, an intoxicated man is not welcomed by his mess, his comrades preferring that he should be put out of the way in cells. It was impossible to keep liquor out of the ship. Men would bring it aboard in little bladders concealed in their neckties. Excess was the rule in many ships. On Christmas Day, for instance, it was not advisable for an officer to go on the lower deck, which was given up to license. I remember one man who ate and drank himself to death on Christmas Day. There he lay, beside a gun, dead. Other cases of the same kind occurred in other ships.

The rations were so meagre that hunger induced the men constantly to chew tobacco. For the same reason I chewed tobacco myself as a boy. Nor have I ever been able to understand how on such insufficient and plain diet the men were so extraordinarily hardy. They used to go aloft and remain aloft for hours, reefing sails, when a gale was blowing with snow and sleet, clad only in flannel (vest) serge frock and cloth or serge trousers, their heads, arms and lower part of their legs bare. Then they would go below to find the decks awash in a foot of water, the galley fire extinguished, nothing to eat until next meal time but a biscuit, and nothing to drink but water.

Seamen often curse and swear when they are aloft furling or reefing sails in a gale of wind; but I have never heard a sailor blaspheme on these occasions. Their language aloft is merely a mode of speaking. Although in the old days I have heard men blaspheme on deck, blasphemy was never heard aloft in a gale. To be aloft in a whole gale or in a hurricane impresses the mind with a sense of the almighty power of the Deity, and the insignificance of man, that puny atom, compared with the vast forces of the elements.

In later life, I once said to a young man whom I heard using blasphemous language in a club:

"If you were up with me on the weather yard-arm of a topsail yard reefing topsails in a whole gale, you would be afraid to say what you are saying now. You would see what a little puny devil a man is, and although you might swear, you would be too great a coward to blaspheme."

And I went on to ram the lesson home with some forcible expressions, a method of reproof which amused the audience, but which effectually silenced the blasphemer.

The fact is, there is a deep sense of religion in those who go down to the sea in ships and do their business in the great waters. Every minister of God, irrespective of the denomination to which he belongs, is treated with respect. And a good chaplain, exercising tact and knowing how to give advice, does invaluable service in a ship, and is a great help in maintaining sound discipline, inasmuch as by virtue of his position he can discover and remove little misunderstandings which cause discontent and irritation.

The discomforts of the Old Navy are unknown to the new. The sanitary appliances, for instance, were placed right forward in the bows, in the open air. If the sea were rough they could not be used. On these occasions, the state of the lower deck may with more discretion be imagined than described. As the ship rolled, the water leaked in through the rebated joints of the gun-ports, and as long as a gale lasted the mess-decks were no better than cesspools. It is a curious fact that in spite of all these things, the spirits of both officers and men rose whenever it came on to blow; and the harder it blew, the more cheery everyone became. The men sang most under stress of weather; just as they will to-day under the same conditions or while coaling ship. After a gale of wind, the whole ship's company turned-to to clean the ship.

In those days the men used to dress in cloth trousers and tunic with buttons. The men used to embroider their collars and their fronts with most elaborate and beautiful designs. They had two hats, a black hat and a white hat, which they made themselves. The black hats were made of straw covered with duck and painted. Many a man has lost his life aloft in trying to save his heavy black hat from being blown away.

The fashion of wearing hair on the face was to cultivate luxuriant whiskers, and to "leave a gangway," which meant shaving upper lip, chin and neck. Later, Mr. Childers introduced a new order: a man might shave clean, or cultivate all growth, or leave a gangway as before, but he might not wear a moustache only. The order, which applied to officers and men (except the Royal Marines) is still in force.

Steam was never used except under dire necessity, or when entering harbour, or when exercising steam tactics as a Fleet. The order to raise steam cast a gloom over the entire ship. The chief engineer laboured under considerable difficulties. He was constantly summoned on deck to be forcibly condemned for "making too much smoke."

We were very particular about our gunnery in the Marlborough; although at the same time gunnery was regarded as quite a secondary art. It was considered that anyone could fire a gun, and that the whole credit of successful gunnery depended upon the seamanship of the sailors who brought the ship into the requisite position. The greater number of the guns in the Marlborough were the same as those used in the time of Nelson, with their wooden trucks, handspikes, sponges, rammers, worms and all gear complete. The Marlborough was fitted with a cupola for heating round-shot, which were carried red-hot to the gun in an iron bucket. I know of no other ship which was thus equipped.

The gunnery lieutenant of the Marlborough, Charles Inglis, was gifted with so great and splendid a voice, that, when he gave his orders from the middle deck, they were heard at every gun in the ship. We used to practise firing at a cliff in Malta Harbour, at a range of a hundred yards or so. I used to be sent on shore to collect the round-shot and bring them on board for future use. I remember that when, in the course of a lecture delivered to my men on board the Bulwark more than forty years afterwards, I related the incident, I could see by their faces that my audience did not believe me; though I showed to them the shot-holes in the face of the cliff, which remain to this day. On gunnery days, all fires were extinguished, in case a spark should ignite the loose powder spilt by the boys who brought the cartridges to the guns, making a trail to the magazines. At "night quarters," we were turned out of our hammocks, which were lashed up. The mess-tables were triced up overhead. The lower-deck ports being closed, there was no room to wield the wooden rammer; so that the charges for the muzzle-loading guns were rammed home with rope rammers. Before the order to fire was given, the ports were triced up. Upon one occasion, so anxious was a bluejacket to be first in loading and firing, that he cherished a charge hidden in his hammock since the last night quarters, a period of nearly three months, and, firing before the port was triced up, blew it into the next ship.

In those days, the master was responsible for the navigation of the ship. He was an old, wily, experienced seaman, who had entered the Service as master's mate. (When I was midshipman in the Defence, the master's assistant was Richard W. Middleton, afterwards Captain Middleton, chief organiser of the Conservative Central Office.) The master laid the course and kept the reckoning. As steam replaced sails, the office of master was transferred to the navigating officer, a lieutenant who specialised in navigation. The transformation was effected by the Order in Council of 26th June, 1867.

The sail-drill in the Marlborough was a miracle of smartness and speed. The spirit of emulation in the Fleet was furious. The fact that a certain number of men used to be killed, seemed to quicken the rivalry. Poor Inman, a midshipman in the Marlborough, a great friend of mine, his foot slipping as he was running down from aloft, lost his life. His death was a great shock to me.

The men would run aloft so quickly that their bare feet were nearly indistinguishable. Topmasts and lower yard were sent down and sent up at a pace which to-day is inconceivable.

I once saw the captain of the maintop hurl himself bodily down from the cap upon a hand in the top who was slow in obeying orders. That reckless topman was Martin Schultz, a magnificent seaman, who was entered by the captain direct from the Norwegian merchant service, in which he had been a mate.

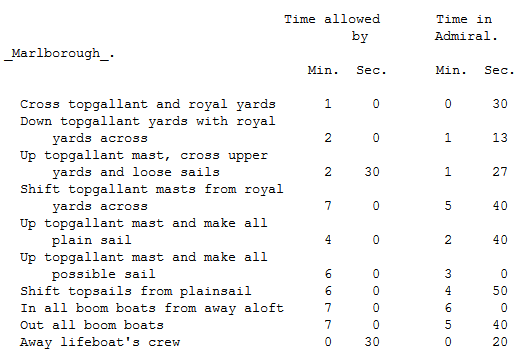

Mr. George Lewis, an old topmate of mine, who was one of the smartest seamen on board H.M.S. Marlborough, has kindly sent to me the following interesting details with regard to the times of sail-drill and the risks incidental to the evolutions.

What Mr. Lewis means by "admiral's time," let him explain in his own words. "When our admiral" (Sir William Martin) "was captain of the Prince Regent, which was considered the smartest ship in the Navy, he brought all her times of all her drills to the grand old Marlborough along with him; and you know, my lord, that he allowed us six months to get our good old ship in trim before we drilled along with the Fleet; but we started to drill along with the Fleet after three months, and were able to beat them all."

"Now, my lord," continues Mr. Lewis, "I come to one of the smartest bits of our drill. When we were sailing in the Bay of Naples under all possible sail, our captain wanted to let the world see what a smart ship he had and what a smart lot of men was under him. From the order 'Shift topsails and courses make all possible sail again'" – which really means that the masts were stripped of sails and again all sails were hoisted – "Admiral's time 13 minutes, our time 9 minutes 30 seconds. All went without a hitch, within 400 yards of our anchorage."

Mr. Lewis proceeds to recount a very daring act of his own. "We were sending down upper yards and topgallant mast one evening, and it was my duty to make fast the lizard. But I could only make fast one hitch, so I slid down the mast rope and it turned me right over, but I managed to catch the lizard and hold on to it, and so saved the mast from falling on the hundred men that were in the gangway. No doubt if it had fallen on them it would have killed a good many…"

What happened was that Lewis, in the tearing speed of the evolution, not having time properly to secure the head of the mast as it was coming down, held the fastening in place while clinging to the mast rope and so came hurtling down with the mast. He adds that he "felt very proud" – and well he might – when the captain "told the admiral on Sunday that I was the smartest man aloft that he had ever seen during his time in the Service." He had an even narrower escape. "I was at the yard-arm when we had just crossed" (hoisted into place). "I was pulling down the royal sheet and someone had let it go on deck, and I fell backwards off the yard head-foremost. I had my arm through the strop of the jewel block, and it held me, and dropped me in the topmast rigging, and some of my topmates caught me."

Mr. Lewis himself was one of the smartest and quickest men aloft I have ever seen during the whole of my career. The men of other ships used to watch him going aloft. "My best time," he writes – and I can confirm his statement "from ''way aloft' to the topgallant yard-arm was 13 seconds, which was never beaten." It was equalled, however, by Ninepin Jones on the foretopgallant yard. The topgallant and royal yard men started from the maintop, inside of the topmast rigging, at the order '"way aloft." The height to be run from the top, inside of the topmast rigging, to the topgallant yard-arm was 64 feet. From the deck to the maintop was 67 feet. At one time, the upper-yard men used to start from the deck at the word "away aloft"; but the strain of going aloft so high and at so great a speed injured their hearts and lungs, so that they ascended first to the top, and there awaited the order "away aloft."

The orders were therefore altered. They were: first, "midshipmen aloft," when the midshipmen went aloft to the tops; second, "upper-yard men aloft," when the upper-yard men went aloft to the tops, and one midshipman went from the top to the masthead.

At the evening or morning evolution of sending down or up topgallant masts and topgallant and royal yards, only the upper-yard men received the order, "upper-yard men in the tops." The next order was "away aloft," the upper-yard men going to the masthead.

At general drill, requiring lower- and topsail-yard men aloft, as well as upper-yard men, the orders were: first, "midshipmen aloft"; then "upper-yard men in the tops"; then, "away aloft," when the lower- and topsail-yard men went aloft to the topsail and lower yards, and the upper-yard men went aloft to the masthead.

These arrangements applied of course only to drill. In the event of a squall or an emergency, the men went straight from deck to the topgallant and royal yards.

Mr. Lewis's performance was a marvel. Writing to me fifty years afterwards, he says: – "I think, my lord, it would take me a little longer than 13 seconds now to get to the maintopgallant yard-arm and run in again without holding on to anything, which I have done many hundreds of times."

The men would constantly run thus along the yards – upon which the jackstay is secured, to which again the sail is bent, so that the footing is uneven – while the ship was rolling. Sometimes they would fall, catching the yard, and so save themselves.

The foretopgallant-yard man, Jones, was as smart as Lewis, though he never beat Lewis's record time. These two men were always six to ten ratlines ahead of the other yard men, smart men as these were. One day Jones lost a toe aloft. It was cut clean off by the fid of the foretopgallant mast. But Jones continued his work as though nothing had happened, until the drill was ended, when he hopped down to the sick bay. He was as quick as ever after the accident; and the sailors called him Ninepin Jack.

Another old topmate, Mr. S. D. Sharp, writing to me in 1909, when I hauled down my flag, says: – "I was proud of the old Marlborough and her successor up the Straits, the Victoria. They were a noble sight in full sail with a stiff breeze. No doubt the present fleet far excels the old wooden walls, but the old wooden walls made sailors. But sailors to-day have to stand aside for engine-men. Going round Portsmouth dockyard some few years since, I was very sad to see the noble old Marlborough a hulk" (she is now part of H.M.S. Vernon Torpedo School), "laid aside, as I expect we all shall be in time" (Mr. Sharp is only between seventy and eighty years of age). "I am doubtful if there are many men in the Navy to-day who would stand bolt upright upon the royal truck of a line-of-battle ship. I was one of those who did so. Perhaps a foolish practice. But in those days fear never came our way."