полная версия

полная версияSouth London

She, too, had to retire to the seclusion of Bermondsey, where she could sit and watch the ships go up and down, and so feel that the world, with which she had no more concern, still continued. It has been suggested that she retired voluntarily to the Abbey. Such a retreat was not in the character of Elizabeth Woodville, so long as there was a daughter or a kinsman left to fight for. Like Katharine of Valois, she made an end not without dignity. Witness the following clause in her will: —

Item. Whereas I have no worldly goods with which to do the Queen's Grace, my dearest daughter, a pleasure, neither to reward any of my children, according to my heart and mind, I beseech God Almighty to bless her Grace with all her noble Issue, and, with as good a heart and mind as may be, I give her Grace aforesaid my blessing and all the aforesaid my children.

In this chapter it has been my endeavour to restore an ecclesiastical foundation which has somehow dropped out of history and become no more than a name. If this were a history of South London it would be necessary to devote an equal space to other houses; to the churches and to the two ancient hospitals 'Le Loke' and St. Thomas's. It is impossible, even in these narrow limits, to speak of the religious foundations of South London without mention of the other great House, more ancient than that of Bermondsey. Few Americans who visit London leave it without paying a pilgrimage to the venerable and beautiful church which glorifies Southwark. There were great marriages and great functions held in the Church of St. Mary Overy: Gower, that excellent poet whom the professors of literature praise and nobody reads, died and lies buried in this church; it was the church of the playerfolk: here lie buried Edmund Shakespeare, John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, and Philip Henslow. Here lie buried, in that 'sure and certain hope' which the Church allows even to them, the rufflers, 'roreres' and sinners of Bank Side and Maiden Lane; the brawlers and the topers and the strikers of the Bear Garden and the Bull Baiting. Here were tried notable heretics: Hooper and Rogers, and many more, while Gardiner and Bonner thundered and bullied. From this church the martyrs went forth to meet the flames. The people of Southwark needed not to cross the river in order to learn such lessons as the martyrdoms had to teach them. The stake was set up in St. George's Fields, where they could read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest the undesigned teaching of Bonner and his friends.

It is the custom of historians to point to the martyrdom of Cranmer and the Bishops as the chief cause of the overwhelming Protestant reaction. So great was the horror, they say, of the people at the death of the Archbishop, that the whole nation was roused – and so on. For myself I like to think that, as the people would feel now, so, mutatis mutandis, they felt then. Was there any such mighty horror felt in London when Cranmer died in Oxford? Not so much horror, I believe, as when from their own ranks, from their own houses, from their own families, men and women and boys were taken out and led to execution. Violent deaths – by beheading, by hanging, by the flames – were witnessed every day. How many were hanged by Henry VIII.? The deaths of nobles did not touch the people; they looked on unmoved while the most innocent and most holy men in the country – the blameless Carthusians – suffered death as traitors; they looked on at the death of Sir Thomas More; when witches were burned they looked on. It was when they saw their own brothers, sisters, cousins, dragged out and put to death without a cause, that they began to doubt and to question. Nay, I think it was not the manner of death that affected them, because burning was a thing so common: it was the sentence itself passed on honest and godly folk, and the behaviour of the people at their death. Tender women chained to the stake suffered without a groan, only praying loudly till death came; people remembered, they recalled with tears afterwards, how the martyr and his wife and his children knelt on the ground for one last prayer before the stake; they remembered how the sufferer stepped into his place with a smiling face and welcomed the fiery lane that led him to the place where he longed to be: was this, they asked, the courage inspired of God, or of the devil? They remembered how another washed his hands in the mounting and roaring flames; how the clouds parted at the prayer of another, and the smiling sun of heaven shone upon him; and it was even like unto the countenance of the Blessed Lord. The sight and the remembrance of the sufferings of their own folk, not the execution at a distance of an Archbishop and a few Bishops, moved the people and remained with them, and enveloped the Church of Rome with a hatred from which it has not wholly recovered even in these latter days.

The foundation of St. Thomas's Hospital belongs to both the great Houses of Southwark.

It was the general Rule in all religious Houses that there should be a provision for the poor, the sick, and those who were orphans. St. Mary Overy had a hospital adjoining the priory which was an almshouse certainly, and probably an orphanage as well. It was under the care of the Archdeacon of Surrey. Attached to St. Saviour's was an almonry intended for the same purpose. But the Abbey was entirely secluded: it lay far from any highway; there were no houses, except farm buildings for the monastery's labourers; there were no poor, no sick, and no orphans. So that, when the great fire of 1213 destroyed Southwark and crossed the river by the Bridge into London, the monks of St. Saviour's bethought them that to make their almonry useful it would be well to rebuild it half a mile to the west, on the Southwark Causeway. This was done, and the Hospital of St. Mary was united with it, and the new foundation which Bishop Peter de Rupibus most liberally endowed was named after St. Thomas. At first it was not a hospital especially for the sick, as St. Bartholomew's and St. Mary of Spittal. It was a fraternity like St. Catherine's by the Tower, for brethren and sisters under a master, with bedesmen and women, and a school, and an infirmary; but not, as St. Bartholomew's was from the beginning altogether, only a hospital for the sick.

As for the religious life of the place, it was in most respects like that of London. There were no houses for Friars, but the Friars came across the river en quête, 'mumping,' on their begging rounds; and in the taverns were put up boxes for the contributions of the faithful (towards the end these contributions fell off sadly). There was plenty of life and colour in the streets: serving men in bright liveries of the great Houses – the Bishops of Winchester and Rochester, the Abbots of Lewes, Hyde, and Battle – went about their errands; there were Gilds, notably that of St. George, which had their processions and their days: there were crosses and images of saints, at which the passer-by doffed his hat – in the wall of Lambeth Palace was an image of St. Thomas à Becket overlooking the river, to which every waterman and bargee paid reverence.

Some of the punishments of the time were ordered by the Church. There was whipping, but not the terrible murderous flogging of the eighteenth century; there were hangings, but not for everything. Mostly to the credit of the Church, punishment was designed not to crush a man, but to shame him into repentance, and to give him a chance of retrieving his character. A man might be set in the stocks, or put in pillory, and so made to feel the heinousness of his offence. This punishment was like that which is inflicted on a schoolboy: the thing done, the boy is taken back to favour. The eighteenth century branded him, imprisoned him, transported him, made a brute of him, and then hanged him. Did a woman speak despitefully of authority? Presumptuous quean! Set her up in the cage besides the stoulpes of London Bridge, that everyone should see her there and should ask what she had done. After an hour or two take her down; bid her go home and keep henceforth a quiet tongue in her head. This leniency was only for offences moral and against the law. For freedom of thought or doctrine there was Bishop Bonner's better way. And it was a way inhuman, inflexible, unable to forgive.

CHAPTER IV

THE ROYAL HOUSES OF SOUTH LONDON

All round London, like beads upon a string, were dotted Royal Houses, Palaces, and Hunting Places. On the north side were Westminster, Whitehall, St. James's, Kensington, Shene, Theobald's, Hatfield, Cheshunt, King's Langley, Hunsdon, Havering-atte-Bower, Stepney, the Tower; on the south side were Kennington, Eltham, Greenwich, Kew, Hampton, Windsor, a tradition attaching to Streatham, and the House of Nonesuch, built by Henry VIII. at Cheam. Most of these royal houses are now clean forgotten. Eltham preserves some ruins left of Edward IV.'s buildings; it still shows the moat and the old bridge, and the line of its former wall; but tradition, which has quite forgotten its memories of the Edwards and the Tudors, describes it as the Palace of King John. The sailors – now, alas! also gone – have deprived Greenwich of Edward VI. and Elizabeth. Theobald's is gone altogether, Nonesuch is wholly cleared away. Of Kennington, of which I have to speak in this place, not one stone remains upon another; not a vestige is above ground; the people on the spot know of no remains underground; its very memory is gone and forgotten: there is not even a tradition left, although part of the ruins were still standing only a hundred years ago.

The reason for this oblivion is not far to seek. The palace was deserted; it was pulled down before 1607 – Camden says that even then there was not a stone remaining – there was not a single house within half a mile in every direction. There was no one, when the last stones had been carted away, left to remember or to remind his children that there had been a palace on this spot. Another house was built here, but no tradition attached to it. Two hundred years passed, and then came the destruction of the second house; in 1745 there was not even a cottage near the spot. This being so, it is not difficult to understand why the site was forgotten.

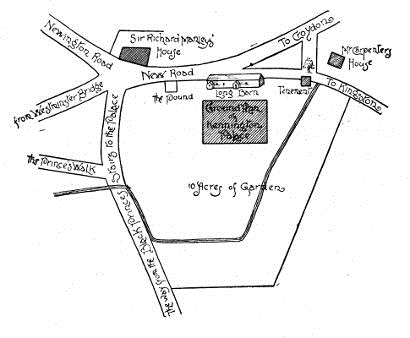

The moat remained, however, and apparently some of the substructures; a building of stone and thatch, part of the offices of the palace, also stood. They called it the 'Long Barn,' and when the distressed Protestants were brought over here in 1700 as many as the place would hold were crammed into the Long Barn. Market gardens lay all over the country between Kennington Road and Lambeth, and on the site of the palace there was not a single person left who could carry on the tradition of the king's house that once stood here. Roque, the map-maker of 1745, knew nothing about it. In 1795 the Long Barn was taken down. At the beginning of the century houses began to rise here and there; streets began to be formed: at least three streets cross the gardens and the site of the palace; but there is not one tradition of a place which, as we shall see, was full of history for six hundred years. 'Is this fame?' might ask the king who crowned himself here, the king who died here, the king who was brought up here, the kings who kept their Christmas feast here, the kings who here received their brides, held Parliament, and went out a-hunting.

The king who crowned himself here was Harold Harefoot, son of Cnut – that is to say, it was at 'Lambeth,' and there was no other house at Lambeth.

SKETCH MAP

The king who died in this house was that young Dane who appears to have been an incarnation of the ideal Danish brutality. He dragged his brother's body out of its grave and flung it into the Thames; he massacred the people of Worcester and ravaged the shire; and he did these brave deeds and many others all in two short years. Then he went to his own place. His departure was both fitting and dramatic. For one so young it showed with what a yearning and madness he had been drinking. He went across the river – there was, I repeat, no other house in Lambeth except this, so that it must have been here – to attend the wedding of his standard-bearer, Tostig the Proud, with Goda, daughter of the Thane Osgod Clapa, whose name survives in his former estate of Clapham. A Danish wedding was always an occasion for hard drinking, while the minstrels played and sang and the mummers tumbled. When men were well drunken the pleasing sport of bone throwing began: they threw the beef bones at each other. The fun of the game consisted in the accident of a man not being able to dodge the bone which struck him, and probably killed him. Archbishop Alphege was thus killed. The soldiers had no special desire to kill the old man: why couldn't he enter into the spirit of the game and dodge the bones? As he did not, of course he was hit, and as the bone was a big and a heavy bone, hurled by a powerful hand, of course it split open his skull. One may be permitted to think that perhaps King Hardacnut, who is said to have fallen down suddenly when he 'stood up to drink,' did actually intercept a big beef bone which knocked him down; and as he remained comatose until he died, the proud Tostig, unwilling to have it said that even in sport his king had been killed at his wedding, gave out that the king fell down in a fit. This, however, is speculation.

Forty years after this event, when Domesday Book was compiled, the place was in the possession of a London citizen, Theodric by name and a goldsmith by trade. It was still a royal manor, because the goldsmith held it of Edward the Confessor. It was then valued at three pounds a year. It is impossible to arrive at the meaning of this valuation. We may compare it with that of other estates, with the rental and price of other lands, with the cost of provisions, and with the wages and pay of servants and officers; and when we have done all, we are still very far from understanding the value of money then or at any subsequent time. There are, you see, so many points which the writers on the value of money do not take into consideration. There is the price of bread; but then there were so many kinds of bread – wheaten bread, barley bread, oat bread, rye bread; and how much bread did a family of the working class consume? Flesh, fish, fowl, but how much of either did the working classes enjoy? Rent? But on the farms the "villains" paid no rent. There is, in a word, not only the market prices that have to be considered, but the standard of comfort – always a little higher than the practice – and the daily relations of the demand to the supply. So that when we read that this manor of Kennington was worth three pounds a year we are not advanced in the least. As most of the land was still marshy and useless, we may understand that the value was low.

We next hear of Kennington in 1189, when King Richard granted it on lease, or for life, to Sir Robert Percy with the title of Lord of the Manor. Henry III. came here on several occasions; here he held his Lambeth Parliament. He kept his Christmas here in 1231. Great was the feasting and boundless the hospitality of this Christmas, at which this king lavished the treasures of the State.

The site of the palace is indicated in the accompanying map. If you walk along the Kennington Road from Bridge Street, Westminster, you presently come to a place where four roads meet, Upper Kennington Lane on the left, and Lower Kennington Lane on the right; the road goes on to the Horns Tavern and Kennington Park. On the right-hand side stood the palace. In the year 1636 a plan of the house and grounds was executed; but by that time the mediæval character of the place was quite forgotten. It was a square house, probably Elizabethan; the home of King Henry III. at some time or other had been completely taken away. The site of the moat, however, was left, and there was still standing the 'Long Barn.' The only way to find out what the palace really was in the thirteenth or fourteenth century is to compare it with another palace built under much the same conditions, and intended to serve the same purpose. Fortunately there still stand, some miles to the east of Kennington, at Eltham, important remains of such a contemporary palace, with a description of the place as it was before it was allowed to fall into ruins.

We are not at this moment concerned with the history of Eltham. Sufficient to note that it was a great and stately place for five hundred years and more; that it passed through the hands of Bishop Odo; of the Mandevilles; of the De Vescis; of Bishop Anthony Bec; and of Geoffrey le Scrope of Masham. As a royal residence its history begins with Henry III., who kept his Christmas here in 1270, and ends with Elizabeth, who came over here occasionally from Greenwich. Here Isabella, wife of Edward II., gave birth to a son, John of Eltham. The greatest builder at Eltham was Edward IV.

The house in 1649, fifty years after Elizabeth had visited it, is said to have contained a chapel, a banqueting-hall, rooms on the ground floor and first floor called the King's side and the Queen's side. There were buildings and rooms of all kinds round the courtyard. The number of chambers in all was very great, and it is said, further, that the large courtyard covered a whole acre in extent. Such an area would give about two hundred and ten feet to each side of a square. This would be large for a college at Oxford or Cambridge. It would cover about the same area as that of New Palace Yard. There were, however, other courts; four courts in all are spoken of. The lesser courts were used for the 'service,' the kitchens, butteries, pantries, stables, rooms for the servants, the barracks for the men-at-arms who accompanied the king, the grooms, armourers, makers and menders, bakers and brewers, cooks and scullions, and the women servants, and the wives and the children. A strong stone wall, battlemented, with loopholed turrets, surrounded the palace; a broad and deep moat defended the wall; the bridge which crossed the moat had a drawbridge; the gate had its portcullis. The palace, in a word, was a fortress, for there was never a king in England who would have dared to keep his court, or to sleep, in an unfortified manor house, or outside a fortress – certainly not Henry III. or Edward IV. – unless, of course, it was on the tented field in the midst of his army.

The existing remains of the palace correspond to this description. There is the moat, deep and broad; there is the bridge, the drawbridge gone. Within, the most important ruin is that of Edward IV.'s banqueting hall. This is a most noble chamber, with a roof of oak as perfect as when it was built; the two magnificent bays remain, with the double row of windows. It would be difficult to find a finer banqueting hall in the whole country than that of Eltham. In the grounds, the traces of the wall and those of other buildings ought to make it possible, with a very little excavation, to trace a plan of the whole house.

As was Eltham, so was Kennington. Both places were built for the same purpose about the same time. Both were castles erected on a plain without the aid of hillock, mound or running stream – unless the moat at Kennington was fed by one of the many streams of South London. The plan of 1636 shows approximately the line of the wall; the stream or the ditch marks the course of the moat; the 'Long Barn' on the east side of the palace belonged to the 'service' – it was kitchens, stables, armoury, brewery, or granary. The house itself had its principal entrance on the north. This is certain, because all the supplies were brought by what is now Kennington Road either from Westminster Ferry or from Southwark. A gate on this side simplified the transference which took place when the court moved from one place to another; when everything – bedding, blankets, utensils of all kinds, plate, batterie de cuisine, the workmen with their tools, the wardrobe of king and queen – was packed up and carried from Westminster over the ferry to Kennington, or from Kennington to Woolwich. Provisions and goods sent up from the City were also landed at Stangate, Lambeth, so as to get as short a land journey as possible. For these reasons I place the principal gate at the north.

I have seen it stated – I know not with what truth – that the people of the streets now on the site have found substructures beneath their houses. If so, one would expect, what one cannot find, some tradition to account for the existence of these stone vaults.

Such was the vanished Palace of Kennington: a fortress of the Lambeth Marsh, a place for keeping Christmas, a royal residence; now completely vanished.

Two other royal houses there were in South London, neither of which can be compared with Kennington. Greenwich, for instance, which appears in history from the time of King Alfred. Edward I., Henry IV., Henry V., Edward IV., Henry VII., Henry VIII., Edward VI., and Elizabeth – all had more or less to do with Greenwich. When Henry VIII. completed his buildings here he deserted Eltham; he left, that is, the mediæval fortress for the modern house. His Greenwich was not fortified. The accompanying view of it shows that it possessed none of the characteristics of the ancient residence, half castle, half manor house. Greenwich, however, before Henry rebuilt it, was a fortified castle. Had we a plan of Greenwich of the fourteenth century it would most certainly resemble those of Eltham and of Kennington, with certain small differences, just as one Benedictine monastery resembles in its general disposition another Benedictine monastery, and one Norman castle in general terms, and allowing for the site, resembles another.

The other house of which I have spoken is that of Nonesuch. This house was not a reconstruction and an adaptation with much of the ancient work: it was newly built and furnished entirely by Henry VIII. There was no suspicion of battlements, no pretence at a fortification; the house stood open and unprotected save by the order maintained by the strong king. It was not beautiful according to our ideas; nor was it what we now call a Tudor house; it bears upon it every mark of the builder's interference with the architect. The outside walls of Nonesuch were decorated by certain bas-reliefs representing subjects from the heathen mythology. The house was pulled down by the Duchess of Cleveland, to whom Charles II. gave it. Nonesuch, however, has nothing to do with Kennington, and must not detain us.

Let us next consider what it means when the king is said to have kept his Christmas at a place.

During the festival – for twenty days – he kept open house, nominally. That is to say, all comers received food and drink: his guests, one supposes, were bidden. Every day during the festival the king sat at the feast wearing his crown and his robes of royal state. Richard II., the most prodigal of all princes that ever lived, entertained every day no fewer than ten thousand persons at his palace. What the number was at Christmas no one knows. In addition to the ordinary following of the court – a huge army of chaplains, canons, scribes, secretaries, gentlemen archers, and servants – there were the bishops and abbots, the peers and barons, who came to the Christmas feast, each attended by his own following of knights and esquires and men in livery. For the entertainment of this enormous company what a huge establishment would be needed! The organisation was complete; everything was in departments, each under the yeomen: the chambers, the wardrobe, the kitchens, the stables, the cellars. Yet what an army in each department! Then, since at Christmas time we look for amusement, there was the Master of the Revels, and with him an extensive and variegated following; among them were all those who played on the different instruments of music, those who sang, the buffoons, tumblers, and mummers, the dancing girls. It was in the time of Henry III. that these performances were brought over for the delectation of the English court – perhaps with the pious intention of showing what joys and attractions awaited the Crusaders in the Holy Land itself.

Hall's account of the festivities of a Christmas a hundred and fifty years later than the time of Richard II. is as follows: —

'The Kyng this yere kept the feast of Christmas at Grenewiche, wher was suche abundance of viands served to all comers of any honest behaviour, as hath been few times seen; and against New Yeres night was made, in the Hall, a castle, gates, towers, and dungion, garnished with artilerie, and weapon after the most warlike fashion: and on the frount of the castle was written, Le Fortresse Dangerus, and within the castle were six ladies clothed in russet satin laide all over with leves of golde, and every owde knit with laces of blewe silke and golde; on ther heddes, coyfes and cappes all of golde. After this castle had been carried about the hal, and the Quene had behelde it, in came the Kyng with five other appareled in coates, the one half of russet satyn, spangled with spangles of fine golde, the other halfe riche cloth of gold; on their heddes cappes of russet satin embroudered with workes of fine gold bullion. These six assaulted the castle: the ladies seyng them so lustie and coragious were content to solace with them, and upon farther communication to yeld the castle, and so thei came down and daunced a long space. And after the ladies led the knightes into the castle, and then the castle sodainly vanished out of their sight.