полная версия

полная версияFlorizel's Folly

September 5-7. – 'In the high winds of Wednesday night, the Prince of Wales's Marquee, in the Camp at Brighton, was blown down; his Royal Highness, however, suffered nothing; for, except on the nights when he is Colonel of the Camp, his residence is in the Pavilion. Many of the officers and men had their tents blown down on the same night.'

This marquee was a very splendid and spacious affair, with a kitchen and all sorts of conveniences attached. Indeed, Florizel was ever attentive to his own comfort, vide the following account of his new travelling-carriage:

August 22-24. – 'The Prince of Wales has just built a long carriage for travelling – it is so constructed, that, in a few moments, it forms a neat chamber, with a handsome bed, and every other convenience for passing the night in it, on the road, or in a camp.'

It is all very nice to have travelling-carriages and marquees, and whatever one's soul desires, but if the income is a fixed one, albeit over £70,000 a year, there must be a limit to expenditure. Poor Florizel was deeply in debt, and one of his best friends, the Earl of Malmesbury, tells us about it:71

'Landed at Dover on Saturday, June 2nd, 1792… Saw Prince of Wales early the 4th – he was very well pleased with what I had done at Berlin, thanked me for it, etc. – Stated his affairs to me as more distressed than ever – Several executions had been in his house – Lord Rawdon had saved him from one – that his debts amounted to £370,000. He said he was trying, through the Chancellor, to prevail on the King to apply to Parliament to increase his income.

'On the Wednesday following, I was with him by appointment. He repeated the same again; said that if the King would raise his revenue to £100,000 a year, he would appropriate £35,000 of it to pay the interest of his debts, and establish a Sinking fund. That, if this could not be done, he must break up his establishment, reduce his income to £10,000 a year, and go abroad. He made a merit of having given up the turf, and blamed the Duke of York for remaining on it. He said (which I well knew before), that his racing stable cost him upwards of £30,000 yearly. He was very anxious, and, as is usual on these occasions, nervous and agitated. He said (on my asking him the question), that he did not stand so well with the King, as he did some months ago, but that he was better than ever with the Queen – that she had advised him to press the King, through the Chancellor, to propose to Mr. Pitt to bring an increase of the Prince's income before Parliament, and that, if this was done, she would use her influence to promote it.

'I strongly recommended his pressing the Queen. He suggested the idea of going to Mr. Pitt directly through the Chancellor, etc. I doubted both the consent of the Chancellor to such a step, at the moment he was going out, and his influence and weight if he did consent to it. I took the liberty of disapproving his going abroad, on any terms, and, particularly, under the circumstances he mentioned; said, that if he should, unfortunately, be reduced to the necessity of lowering his income to the degree he had mentioned, it would be much better to live in England, than out of it. That the showing, in England, that he could reduce his expences, and live economically, would do him credit, prove him in earnest, and if he kept up to such a plan, would, in the event, be much more likely to induce the public to take his situation into consideration, than any attempts through Ministry, Opposition, or even the Queen herself.

'I saw the Prince again on the 7th June, at Carlton House, as before. He repeated the same things, and added, that, if he could not obtain some assurance from the King that he would apply to Parliament in the next Session of Parliament, before this ended, that he should be ruined, and must go abroad – I, again, combated this idea; but he appeared to have a wish and some whim about going abroad, I could not discover. – He talked coldly and unaffectionately about the Duke and Duchess of York, and very slightingly of the Duke of Clarence.

'Colonel St. Leger called on me on the 8th June. He said the Prince was more attached to Mrs. Fitzherbert than ever; that he had been living with Mrs. Crouch72; that she (Mrs. Fitzherbert) piqued him by treating this with ridicule, and coquetted on her side. This hurt his vanity, and brought him back; and he is, now, more under her influence than ever.'

And yet he could sacrifice her, in order to get his debts paid, and himself have a larger income to squander. There was but one way out of his mess: that he must commit bigamy, and deliberately repudiate his wife.

On August 24, 1794, the King wrote thus to Pitt from Weymouth:

'Agreeable to what I mentioned to Mr. Pitt before I came here, I have this morning seen the Prince of Wales, who has acquainted me with his having broken off all connection with Mrs. Fitzherbert, and his desire of entering into a more creditable line of life, by marrying; expressing, at the same time, that his wish is that my niece, the Princess of Brunswick, may be the person. Undoubtedly she is the person who, naturally, must be most agreeable to me. I expressed my approbation of the idea, provided his plan was to lead a life that would make him appear respectable, and, consequently, render the Princess happy. He assured me that he perfectly coincided with me in opinion. I then said that till Parliament assembled, no arrangement could be taken, except my sounding my sister, that no idea of any other marriage may be encouraged.

'G. R.'At this time Lady Jersey, a lady of mature age, had great influence over the Prince, and this probably made his rupture with Mrs. Fitzherbert the easier. The caricaturist (this time J. Cruikshank), who always seems to have been as well posted up in any Court scandal as one of our Society papers, has a picture, August 26, 1794, 'My Grandmother, alias the Jersey Jig, alias the Rival Widows.' Old Lady Jersey, who is taking snuff, sits on the knee of the Prince, who says:

'I've kissed & I've prattled with fifty Grand Dames,And changed them as oft, do you see;But of all the Grand Mammys that dance on the Steine,The Widow of Jersey give me.'Mrs. Fitzherbert, one hand clasping her forehead, and in the other holding a bond for £6,000 per annum, cries distractedly: 'Was it for this Paltry Consideration I sacrificed my – my – my – ? for this only I submitted to – to – ? Oh! shame for ever on my ruin'd Greatness!!!'

It came very suddenly. Both Mrs. Fitzherbert and the Prince were to dine with the Duke of Clarence; the lady was there, but Florizel was not; instead, a letter from him was handed to his wife repudiating her. Lord Stourton had the story from her own lips. Let him tell it:

'Her first separation from the Prince was preceded by no quarrel, or even coolness, and came upon her quite unexpectedly. She received, when sitting down to dinner at the table of William the Fourth, then Duke of Clarence, the first intimation of the loss of her ascendancy over the affections of the Prince; having, only the preceding day, received a note from his Royal Highness, written in his usual strain of friendship, and speaking of their appointed engagement to dine at the house of the Duke of Clarence. The Prince's letter was written from Brighton, where he had met Lady Jersey. From that time she never saw the Prince, and this interruption of their intimacy was followed by his marriage with Queen Caroline; brought about, as Mrs. Fitzherbert conceived, under the twofold influence of the pressure of his debts on the mind of the Prince, and a wish on the part of Lady Jersey to enlarge the Royal Establishment, in which she was to have an important situation.

'Upon her speaking to me of this union (confiding in her own desire that I should disguise from her nothing that I might conceive to be of doubtful character as affecting her conduct to the Prince), I told her I had been informed that some proposals had been made to her immediately preceding the marriage of the Prince, of which her uncle, Mr. Errington, had been the channel, offering some terms upon which his Royal Highness was disposed to give up the match. She told me there was no truth whatever in the report; that a day or two preceding the marriage, he had been seen passing rapidly on horseback before her house at Marble Hill, but that his motive for doing so, was unknown to her; and that, afterwards, when they were reconciled, she cautiously abstained from alluding to such topics; as the greatest interruptions to their happiness, at that period, were his bitter and passionate regrets and self accusations for his conduct, which she always met by saying – "We must look to the present and the future, and not think of the past."

'I ventured, also, to mention another report, that George the Third, the day before the marriage, had offered to take upon himself the responsibility of breaking off the match with the Princess of Brunswick, should the Prince desire it. Of this, too, she told me, she knew nothing; but added, that it was not improbable, for the King was a good and religious man. She owned, that she was deeply distressed and depressed in spirits at this formal abandonment, with all its consequences, as it affected her reputation in the eyes of the world.

'One of her great friends and advisers, Lady Claremont, supported her on this trying occasion, and counselled her to rise above her own feelings, and to open her house to the town of London. She adopted the advice, much as it cost her to do so; and all the fashionable world, including all the Royal Dukes, attended her parties. Upon this, as upon all other occasions, she was principally supported by the Duke of York, with whom, through life, she was always united in the most friendly and confidential relations. Indeed, she frequently assured me, that there was not one of the Royal family who had not acted with kindness to her. She particularly instanced the Queen; and, as for George the Third, from the time she set foot in England, till he ceased to reign, had he been her own father, he could not have acted towards her with greater tenderness and affection. She had made it her constant rule to have no secrets of which the Royal Family were not informed by frequent messages, of which, the Duke of York was, generally, the organ of communication, and, to that rule, she attributed, at all periods, much of her own contentment and ease in extricating herself from embarrassments which would, otherwise, have been insurmountable.'

Compare this paragraph with the ideas of the pictorial satirist on her abandonment. Take, for instance, 'The Rage,' published November 21, 1794. Here we see Mrs. Fitzherbert, having thrown off her Princess of Wales's coronet, with clenched fists and dishevelled hair, sparring at the new Princess of Wales.

Another, which is of the same date, and is called 'Penance for past Folly,' shows Mrs. Fitzherbert weeping, and on her knees, before a Roman Catholic priest, who holds a birch rod in his hand.

The newspapers had an early inkling of the state of affairs between Mrs. Fitzherbert and the Prince, and the following cuttings from the Times of 1794 do not redound much to the paper's credit, or knowledge:

July 21. – 'A certain lady has not been so improvident as the beauteous harlot in the days of Edward. She has, wisely, laid up ample provision for a rainy day; and, therefore, her approach, unlike to that of Shore, is still as likely as ever to make "a little holiday!"'

July 23. – 'We have, hitherto, forborne to mention the report in circulation for many days past, of the final separation between a Gentleman of the most distinguished rank, and a Lady who resides in Pall Mall, until we had an opportunity to ascertain the fact beyond all doubt.

'We are now enabled to state from the most undoubted authority, that a final separation between the parties in question has actually taken place; that the agreements formerly entered into, have been given up by mutual consent; that a new contract has been signed, by which the lady is secured in the possession of £4,000 per annum, for her life, besides retaining her house in Pall Mall, plate, jewels, etc.

'Mrs. Fitzherbert has no intention of retiring into Switzerland, as has been reported. She is looking out for a house at, or near, Margate, where she means to reside for six months, in the society of the Duchess of Cumberland, Lady E. Luttrell, Mrs. Concannon,73 and others of her old acquaintance.'

August 5. – 'Mrs. Fitzherbert, we learn, wished to have a title and £4,000 annuity settled on her, but this was peremptorily refused.'

August 7. – 'Much has been said respecting the jointure settled on Mrs. Fitzherbert, in consequence of a late separation; but the precise fact has never been hitherto stated. – The truth is this: – When the incumbrances of a certain great personage were put in a state of settlement, two, or three years since, £3,000 a year was allotted out of his revenues, for Mrs. Fitzherbert, which has been punctually paid by Mr. Coutts, the banker. This sum has been lately settled on the lady for life; which, with her own private fortune of £1,800 annually, will make her present income £4,800 a year. Unincumbered as she now is, the lady will, probably, be a happier woman than she has ever been.'

CHAPTER XIV

Another camp at Brighton – The Prince's second marriage – His debts – Parliamentary debate thereon – Prince and Princess at Brighton – 'Moral Epistle from the Pavilion at Brighton to Carlton House' – Manners at Brighton, 1796 – Description of the townEARLY in the summer of 1794 another encampment took place at Brighton, about a mile and a half to the west of the town, as it then was. It consisted of about 7,000 men, and did not break up until the second week in November. The Prince was at the Pavilion in May, but not much afterwards. Mrs. Fitzherbert did not go there this year.

The King, in his speech in opening the session of Parliament, on December 30, 1794, said: 'I have the greatest satisfaction in announcing to you the happy event of the conclusion of a treaty for the marriage of my son, the Prince of Wales, with the Princess Caroline, daughter of the Duke of Brunswick; the constant proofs of your affection for my person and family persuade me that you will participate in the sentiments I feel on an occasion so interesting to my domestic happiness, and that you will enable me to make provision for such an establishment, as you may think suitable to the rank and dignity of the Heir apparent to the crown of these kingdoms.'

As soon as possible afterwards the pictorial satirist has (January 24, 1795) The Lover's Dream.

'A thousand virtues seem to lackey her,Driving far off each thing of sin and guilt.'Milton.The Prince is represented as asleep in bed, and dreaming of his coming bride, who is descending from heaven, accompanied by Cupids, and driving away Bacchus, Fox, the Jews, Mrs. Fitzherbert and fiends, racehorses, etc.; and by the bedside are the King and Queen, the former holding a bag labelled £15,000 per annum.

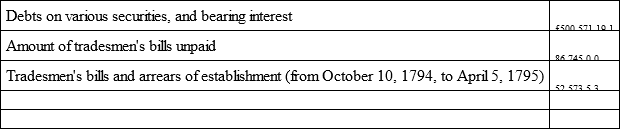

Much Florizel cared for reforming his character; he only wanted to get clear of debts, and have an increased income; and, not caring how he obtained this relief, he committed bigamy on April 8, 1795, in order to obtain the longed-for relief. His debts were, according to a schedule presented to Parliament, up to April 5, as follows:

On April 27 the King sent a message to his faithful Commons respecting an establishment for the Prince and Princess of Wales, and in the last paragraph he says: 'Anxious as his Majesty must necessarily be, particularly under the present circumstances, to relieve the Prince of Wales from these difficulties, his Majesty entertains no idea of proposing to his Parliament to make any provision for this object, otherwise than by the application of a part of the income which may be settled on the Prince; but he earnestly recommends it to the House, to consider of the propriety of thus providing for the gradual discharge of these incumbrances, by appropriating and securing, for a given term, the revenues arising from the Duchy of Cornwall, together with a proportion of the Prince's other annual income; and his Majesty will be ready and desirous to concur in any provisions which the wisdom of Parliament may suggest for the purpose of establishing a regular and punctual order of payment in the Prince's future expenditure, and of guarding against the possibility of the Prince being again involved in so painful and embarrassing a situation.'

On May 14 the House went into Committee on the subject. Pitt pointed out that fifty years previously the Prince's grandfather, as Prince of Wales, had an annual income of £100,000. 'He, therefore, now proposed, that the income of his Royal Highness should be £125,000, exclusive of the Duchy of Cornwall, which was only £25,000 a year more than was enjoyed 50 years ago. This being the only vote he had to propose, he should merely state, in the nature of a notice, those regulations which were intended to be made hereafter. The preparations for the marriage would be stated at £27,000 for jewels and plate; and £25,000 for finishing Carlton House. The jointure of the Princess of Wales, he proposed to be £50,000 a year, being no more than had been granted on a similar occasion.'

The addition to the Prince's income was carried by 241 to 100.

In the course of the debate Pitt proposed that the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall and part of the income of £125,000 should be applied to the payment of the interest of the debts, and to the gradual discharge of the principal; that the sum so taken should be vested in the hands of Commissioners. From the income of £125,000 a year he should propose that £25,000 should be deducted annually for the payment of the debts at 4 per cent., and that the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall should be appropriated as a sinking fund, at compound interest, to discharge the principal of the debts, which they would do in twenty-seven years.

Finally, by an Act which received the royal assent on June 27, 1795 (35 Geo. III., c. 129), £60,000 per annum was to be set apart and vested with Commissioners from the Prince's income, as well as £13,000 per annum from the Duchy of Cornwall, to pay the Prince's debts, a proceeding which found small favour in Florizel's sight.

Of the wretched marriage nothing need be said. Public appearances were kept up until the birth of the Princess Charlotte, and the Prince and his consort visited Brighton together, as we see from the following extracts from the Sussex Weekly Advertiser:

June 22, 1795. – 'Their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales arrived at Brighton between one and two o'clock on Thursday morning last. They alighted at the house of Mr. Hamilton, on the Steine, which is to be made the Royal residence, till the alterations that are going forward at the Pavilion, can be completed.

'In the evening the whole town was illuminated, in honour of their Royal Highnesses' arrival; but the effect of the illumination was greatly lessened by the wetness of the night, as it prevented the lamps with which the Castle, the Libraries, and other houses were decorated, from burning.

'The Prince, we are informed, perambulated the town, in his great coat, to view the different devices.

'Though the untowardness of the weather has, hitherto, obscured the beauties of Brighton from the Princess of Wales, it has had no effect whatever on her Royal Highness's spirits; on the contrary, her cheerfulness and pleasantry strongly bespeak her approbation of the place.

'The Prince, about noon yesterday, set off for town, but we understand his Royal Highness signified his intention of returning to Brighton some time in the course of this day.

'On Wednesday morning, should the weather prove favourable, the Prince and Princess of Wales intend visiting the Camp, when the whole line will be drawn up, and fire a Royal salute, on the occasion. After which, there will be a grand field day.'

June 29. – 'The Prince and Princess of Wales did not visit the Camp, last Wednesday, as was expected, owing to the absence of his Royal Highness, who, on that day, went to town, in order to attend the Privy Council. The whole line was, nevertheless, out, and had a field day.

'On Saturday morning, however, their Royal Highnesses honoured the Camp with their promised visit, when the whole line was drawn up in readiness to receive them; after which, the troops marched to Goldstone Bottom, where they had a very grand field day, and fired a Royal salute, on the occasion.

'We are glad to hear, from the best authority, that the air of Brighton proves extremely agreeable to the above illustrious Princess. Since her arrival at that place, her Royal Highness has enjoyed an excellent flow of spirits, and has frequently been heard to declare she had never before experienced so good an appetite. Her Royal Highness has signified her intention of continuing at Brighton, the whole of the summer.'

July 6. – 'The Prince and Princess of Wales removed from Mr. Hamilton's house, on the Steine, to the Royal Pavilion, on Thursday last.'

They stopped at Brighton till November, and Queen Caroline never again revisited it, as, after the birth of the Princess Charlotte (January 7, 1796), the royal couple separated for good.

The Prince went to Brighton for the season on July 28, 1796, and the Pavilion, as it then was, is thus described in a contemporary pamphlet:74

'The Pavilion is built principally of wood; it is a nondescript monster in building, and appears like a mad house, or a house run mad, as it has neither beginning, middle, nor end; yet, to acquire this design, a miserable bricklayer was despatched to Italy, to gather something equal to the required magnificence, and actually charged two thousand guineas for his expenses. – There are four pillars in scagliola, in a sort of oven, where the Prince dines; and, when the fire is lighted, the room is so hot, that the parties are nearly baked and incrusted: the ground on which it is erected was given to the Prince by the town, for which he allows them fifty pounds yearly, to purchase grog and tobacco; and has so far mended their ways, as to make a common sewer to hold the current filth of the parish.'

The same pamphlet contains 'A Moral Epistle from the Pavilion at Brighton to Carlton House, London,' which gives an account of the style of company kept there:

'When he first nestled here, he was handsome and thin,No razor had then mown his stubbleless chin:He was sportive and careless, bland, upright and young,And I smiled on his feats when he said, or he sung:Then youth bore its own pardon, while stumbling o'er ill,As the passions o'erthrew what was meant by the will.*****I have seen him inwove with a pestilent crew,Who, nine tenths came undone, and the rest to undo!When those caitiffs came thund'ring in impudent state,And drew up their tandems and gigs at my gate,Full of wrath at their daring, I rav'd and I swore,Then I let in an Eddy that slamm'd to the door:But, alas! it avail'd not – 'twas open'd again,And the P – rose, and welcom'd the toad eating train!He, urbane, smil'd on all, where 'twas sin to look sad,As God's light aids, in common, the good and the bad.I tore off Folly's cloak, to exhibit the wrong;How I toil'd to advise, but was stunn'd with a song:I made signs on my plaster to rally them all,But no Daniel was there to decipher the wall. —Ah! I know his large heart, and beneficent plan;Though he's run from the course, yet HE FEELS LIKE A MAN:Though he dissipates seeds of an undeserv'd sorrow,And, gaily, puts off half his ills till the morrow,His radical nobleness knows no decay;He will act, but not cant; – he'll relieve ere he'll pray:As Charity's retinue own, while embrac'd,In his gift he gives twice, 'tis a deed so well grac'd.When their mirth grew to madness, and jests met the ear,Which Philosophy scorns, and no maiden should hear,Convuls'd with disdain, I soon alter'd their note,For I shut up the principal valve of my throat;Till the smoke, in vast volumes, pour'd into the room,And enwrapp'd the loud mob in a horrible gloom,More fœtid than Vulcan inhal'd with his breath;More thick than e'er pass'd o'er the threshold of Death;More choking than Cyclops drank in at their forge;More rank than the reptile of Thebes could disgorge:As they gasp'd, it rush'd down their intestines, and clogg'd 'em,And from pharynx to rectum begrim'd and befogg'd 'em:While, hoarsely, they growl'd at the house, and the smother,Though, by knowing the cause, they had curs'd one another.'Mid their baneful carousals, I've fum'd and I've fretted,Till from kitchen to garret, I've croak'd, and I've sweated;By pressure, I made my joints crack – I can't bawl —And drops, drawn from my heart, ran from every wall:But, his H – s, not knowing my woes, or displeasure,Renew'd the broad catch, and refill'd every measure;While the rascals around him, revil'd the damp mansion,And my marrow, scorch'd up by the fire's expansion:Which so heated my fibres and bones – I mean wood —That a putrescent fever polluted my blood;Which settled behind the bed's head of the P – e,And I've not had my health, or my ease, ever since;Yet I'm sure he would grieve, his politeness is such,Had he known that a lady had suffered so much.Thus they swill'd and re-swill'd, and repeated their boozings,Till their shirts became dy'd with purpureal oozings.When the taster sought wine of a primary sort,I have cough'd 'neath the bin, and shook all the old port,Till 'twas muddy as Will B – ck's brains – yet each varletSaid 'twas as bright as a ruby, and toasting some harlot,Would then smack his lips, in despite of my labour!Oh, ye Gods! how I wish'd for a fist and a sabre,To cut down the hiccupping roist'rers with glee,That is, if their heads could be injur'd by me.When Weltje has cook'd for the half famish'd group,How oft have I belch'd pecks of soot in his soup:Yet e'en that could not drive them from board, or from bed,Though 'twas render'd as black as an Ethiop's head:When I've made it as foul as a Scot's ragged tartan,The rogues gulp'd it down, and all swore it was Spartan.When they've sat near the fire, in knee squeezing rows,I have spit out a coal, and demolished their hose:All my grates have breath'd sulphur to stifle their powers;I'd a watch at my side to beat minutes and hours:When I've seen a Blight glide 'twixt the earth and the skies,I've coax'd in the demon, and ruin'd their eyes:I've edg'd down a poker on legs swell'd with gout,Till the miscreant has roar'd like swine stuck in the snout;When Lord – from my windows was making a beck,I have hurl'd down my sashes, and wounded his neck;Though my rage could but bruise him black, yellow and blue,'Twas a hint that might show what the nation should do:But each knave all the arts of my anger withstood,For the leeches will suck while the body has blood.I'd have prophecied much, had I Cerberus' three tongues;I would fulminate oaths, but, alas! I've no lungs.When they thought 'twas an earthquake that palsied my walls,It was I who was shudd'ring to witness their brawls.There's no office so dirty but they would fulfil;There's no sense of debasement could alter their will:When the munching of immature codlings might gripe him,They would tear out the leaves of the Psalter to wipe him.Yet these summer fed vermin will fly him, if e'erHis wintery fortunes should leave his trunk bare;Then he'll know that but virtue can keep the soul great,As they'd make their past meanness the cause of their hate!I have dropp'd lumps of lime in their glasses while drinking;I've made thieves in the candle to move him to thinking;I have clatter'd my casements and chairs to confound 'em;I have let in the dews and the blast all around 'em;I have elbow'd my timbers 'gainst many a head;I have stirr'd up the sewers to stink 'em to bed:Yet this mass of antipathy marr'd my own liver,And my tears fill'd the gutter like Egypt's deep river.– My eyes, my dear Coz, are exhausted with crying;So I'll give o'er at present – I'm yours till I'm dying.'Pavilion.'We learn what the society at Brighton was like at this time by the following excerpt from the Times of July 13, 1796: