полная версия

полная версияBuffon's Natural History. Volume X (of 10)

Different objects are proposed when we set plants to pass through the winter in shelters exposed to the south, and sometimes it is to expedite vegetation: it is, for example, with this intention, that along espaliers we plant ranges of lettuces, which for that reason are termed winter-lettuces; these will tolerably well resist the frost in whatever part we plant them, but are always most forward in this exposition; at other times, it is to preserve them from the rigour of this season, with an intention of replanting them early in the spring. This practice is also followed in winter cabbages, which are sown in this season along an espalier border. These kind of cabbages, like brocoli, are tender and cannot endure the frost, and would often perish in these shelters, if care were not taken to cover them during the sharp frosts with straw or dung supported on frames.

To forward the vegetation of some plants which will not bear the frost, as green peas, &c. it is usual for that purpose to plant them on borders exposed to the south, besides which, they are defended from sharp frosts when the weather requires it.

It is well known, without being compelled to dwell any longer on this point, that the southern exposition is more proper than all the rest to accelerate vegetation, and we have shewn that this is also what is principally proposed when some plants are set in that exposition to pass through the winter, since, in addition, we are also obliged to make use of coverings to guard those plants which are very delicate from the frost. But we must add, that if there be some circumstances wherein the frost causes more disorders to the southern than to other expositions, there are also many cases which are favourable to this exposition: for example, in winter, when there is any thing to fear from the ice, it frequently happens that the heat of the sun, increased by the reflection of the wall, has sufficient force to dissipate all the humidity, and then the plants are almost perfectly secure against the cold. Besides, dry frosts often happen, which unceasingly act towards the north, and which are scarcely ever felt towards the south. In spring, likewise, we perceive that after a rain which proceeds from the south-west, or south-east, if the wind change to the north, the southern espalier being under the shelter of the wind, will suffer more than the rest; but these cases are very rare, and most often it is after rains, which come from the north-east or north-west that the wind changes to the north, and then the southern espalier having been under shelter from the rain by the wall, the plants there will have less to suffer than the rest, not only because it will have received less rain, but also because there is always less cold here, than in other expositions. It is likewise to be observed that as the sun dries much earth along the espaliers which are to the south, the earth transpires there less than elsewhere.

It is well known that what we have just advanced must be considered as applying also to peach and apricot trees, which it is customary to put in this exposition and in that of the east. We shall only add, that it is not unusual to see peach trees frozen in the east and southern expositions, while those are not so which stand in the west or north; but notwithstanding this we can never rely on having many, nor good peaches in this last exposition, for great quantities of blossoms fall off entirely without setting; others, after having set fall from the trees, and those which remain with difficulty arrive to maturity. I have an espalier of peach-trees in a western exposition, a little declining to the north, which scarcely ever produce any fruit, although the trees are handsomer than those to the southern and northern. We cannot, therefore, avoid the inconveniences of the frost with respect to the southern exposition without feeling others that are worse.

All delicate trees, as fig, laurel, &c. must be set to the south, and great care taken to cover them; it is only requisite to remark that dry dung is preferable for this purpose to straw, because the latter not only does not so exactly cover them, but also from its always retaining some grain which attracts moles and rats, who sometimes eat the bark of trees to quench their thirst in frosty weather, when they can meet with no water to drink, nor herb to feed upon; and however singular this may appear, it is a circumstance which has happened to us several times; but when dung is made use of it must be dry, without which it will heat and make the young branches grow mouldy.

All these precautions are, nevertheless, very inferior to the espaliers in niches, as in that manner plants are sheltered from all winds, except the south, which cannot hurt them; the sun, which warms these places during the day, prevents the cold from being so violent during the night; and over these defended places we may put a slight covering with great facility, which will hold the plants there in a state of dryness, infinitely proper to prevent all the accidents which the spring frosts and ice might produce; and most plants will not suffer from being deprived of their external humidity, because they scarcely transpire in the winter, or in the beginning of spring, so that the humidity of the air is sufficient for their supply.

But since the dew renders plants so susceptible of the spring frost, might we not hope, that from the researches of Messrs. Musschenbroeck and Fay, some inferences may be deduced which may turn to the advantage of agriculture? for since there are some bodies which seem to attract dew, while others evidently repel it, if we could paint, plaster, or wash the walls with some matter which would have the latter effect, it is certain we should have room to expect a more fortunate success than from the precaution taken to place a plank in form of a roof over the espaliers, which cannot prevent the abundance of dew from resting on trees, since Fay has proved that it very often does not fall perpendicularly like rain, but floats in the air, and attaches itself to those bodies it encounters; so that frequently as much dew is amassed under a roof as in places entirely open. It would be easy for us to recapitulate all our observations, and continue to deduce useful consequences, but what we have said must be sufficient to shew the necessity of rooting up all trees which prevent the wind from dissipating mists.

Since by cultivating the earth we cause more exhalations to issue, great attention should be paid not to cultivate them in critical times.

We must expressly declare against sowing kitchen-plants on vine-furrows, as by their transpiration they hurt the vine.

Props should be put to the vines as late as possible. The hedges, which border them on the north side, should be kept lower than the rest. It is preferable to improve vines with mould rather than dung. And in choosing a soil we should avoid those which are in bottoms and grounds which transpire much.

A part of these precautions may be also usefully employed for fruit-trees; with respect, for example, to plants which gardeners are forward to put at the feet of their bushes and along their espaliers.

If there are some parts high and others low in a garden, we should pay attention to sow spring and delicate plants on elevated parts, at least if we do not design to cover them with glasses, &c. but in cases where humidity cannot hurt them it might be often advantageous to choose low places, where they might be sheltered from the north and north-west winds.

We may also profit from what has been said to the advantage of forests, for if we mean to make a reserve of any of the trees, it should never be in parts where the frost is severe; and in planting we should pay attention to put in vallies those trees which can endure the frost better than the oak.

When any considerable fall of timber is made we should make them in roads, beginning always on the north side, in order that the wind, which generally blows in frosty weather, may dissipate that humidity which is so prejudicial to the underwood.

There might be also many other useful consequences drawn from our observations; but we shall content ourselves with having briefly adverted to some, because the ingenious man may supply what we have omitted by paying a little attention to the observations we have mentioned. We are well convinced there are a great number of further experiments to be made on this matter; and perhaps even those which we have related will engage some persons to work on the same subject, and from our hints general and useful advantages may be derived.

ON THE TEMPERATURE OF THE PLANETS

MAN newly created, and even the ignorant man at this day beholds the extent and nature of the universe only by the simple organ of light: to him the earth is but a solid body, whose volume is unbounded, and whose extent is without limits, of which he can only survey small superficial spaces: while the sun and planets seem to be luminous points, of which the sun and moon appear to be the only objects worthy regard in the immensity of the heavens. To this false idea on the extent of nature and the proportions of the universe is joined the still more disproportionate sentiment of superiority. Man, by comparing himself with other terrestrial beings, feels that he ranks the first, and hence he presumes that all was made for him; that the earth was created only to serve for his habitation, and the heavens for a spectacle; and in short the whole universe ought to yield to his necessities, and even his pleasures. But in proportion as he makes use of that divine light, which alone ennobles his being; in proportion as he obtains instruction, he is forced to abate his pretensions; he finds himself lessened in proportion as the universe increases in his ideas, and it becomes demonstrable to him, that the earth, which forms all his domain, and on which unfortunately he cannot subsist without trouble and sorrow, is as small with respect to the universe, as he is with respect to the Creator. In short, from study and application, he finds that there does not remain a possible doubt, that this earth, large and extensive as it may seem to him, is but a moderate sized planet, a small mass of matter, which, with others, has a regular course round the sun: for as it appears our globe is at the distance of at least 33 millions of leagues, and the planet Saturn at 313 millions, the natural conclusion is, that the extent of the sun’s empire is a sphere, whose diameter is 627 millions of leagues, and that the earth, relative to this space, is not more than a grain of sand to the volume of the globe.

However, the planet Saturn, although the furthest from the sun, is not by any means near the confines of his empire: his limits extend much further, since comets pass over spaces beyond that distance, as may be estimated by the time of their revolutions: a comet which like that of the year 1680 revolves round the sun in 575 years must be 15 times more remote from him than Saturn; for the great axis of its orbit is 138 times greater than the distance from the earth to the sun. Hence we must still augment the extent of the solar power 15 times the distance from the sun to Saturn, so that all the space in which the planets are included is only a small province of his domain, whose bounds should be placed at least 138 times his distance from the earth.

What immensity of space! What quantity of matter! For independently of the planets, there is a probability of the existence of 400 or 500 comets, perhaps larger than the earth, which run over the different regions of this vast sphere of which the terrestrial globe only constituting a part, a unity on 191,201,612,985,514,272,000, a quantity represented by numbers, which imagination cannot attain or comprehend.

Nevertheless, this enormous extent, this vast sphere, is yet only a very small space in the immensity of the heavens; each fixed star is a sun, a center of a sphere equally as extensive; and as we reckon more than 2000 of these fixed stars perceived by the naked eye, and as with telescopes we can discover so much the greater number as these instruments are more powerful; the extent of the universe appears to be without bounds and the solar system forms only a province of the universal empire of the Creator; an infinite empire like himself.

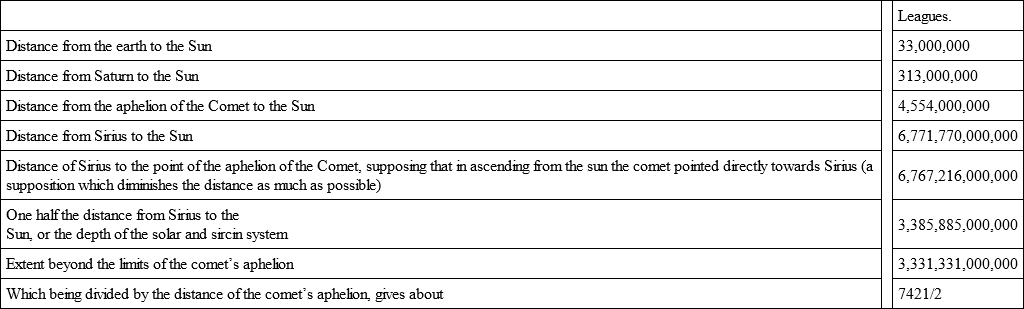

Sirius, the most brilliant fixed star, and which for that reason may be regarded as the nearest sun to our’s, affords to our sight only a second of annual parrallax on the whole diameter of the earth’s orbit, and is therefore at the distance of 6,771,770, millions of leagues distant from us, that is, 6,767,216 millions of leagues from the limits of the solar system, such as we have assigned it after the depth to which the comets immerse. Supposing then, there is an equal space from Sirius to that which belongs to our sun, we shall perceive that we must extend the limits of our solar system 742 times more than it is at present, as far as the aphelion of the comet, whose enormous distance from the sun is nevertheless only a unit on 742 of the total diameter of the solar system.

We can form another idea of our immense distance from Sirius, by recollecting that the sun’s disk forms to our sight an angle of 32 minutes, whereas that of Sirius forms only that of a second; and Sirius being a sun like ours, which we shall suppose of equal magnitude, since there is no reason to conceive it larger or smaller, it would appear to us as large as the sun, if it were but a like distance. Taking therefore two numbers proportional to the square of 32 minutes, and to the square of a second, we shall have 3,686,400 for the distance of the earth to Sirius, and one for its distance to the sun; and as this unit is equal to 33 millions of leagues, we see how many millions of leagues Sirius is distant from us, since we must multiply these 33 millions by 3,686,400; and if we divide the space between these two neighbouring suns, although at so great a distance, we shall see that the comets might be removed to a distance 1,800,000 times greater than that of the earth to the sun without quitting the limits of the solar universe, and without being subjected to other laws than that of our sun, and hence it may be concluded that the solar system for its diameter has an extent, which, although prodigious, nevertheless, forms only a very small portion of the heavens; and we must infer a truth therefrom but little known, namely, that from the sun, the earth and all the other planets, the sky must appear the same.

When in a serene and clear night we contemplate all those stars with which the celestial vault is illuminated, it might be imagined that by being conveyed into another planet more remote from the sun, we should see these glittering stars larger, and emitting a brighter light, since we should be so much nearer to them. Nevertheless, the calculation we have just made demonstrates that if we were placed in Saturn, which is 300 millions of leagues nearer Sirius, it would appear only an 194,021st part bigger, an augmentation absolutely insensible; from which it must be concluded, that the heaven, with respect to all the planets, has the same aspect as it has to the earth. Therefore if even there should exist comets whose periods of revolution might be double, or treble the period of 575 years, the longest known to us; if even the comets in consequence thereof, immerse at a depth ten times greater, there would still be a space 74 or 75 times deeper, to reach the last confines, as well of the solar system, as of the sirian; so that by allowing Sirius as much magnitude as our sun has, and supposing in his system as many or more cometary bodies than there are comets existing in the solar, Sirius will govern them as the sun governs his, and there will remain an immense interval between the confines of the two empires; an interval which appears to be no more than a desart in the vast space, and which must give a suspicion that cometary bodies do exist, whose periods are longer, and which are to a much greater distance than we can determine by our actual knowledge. Sirius may also be a sun much larger and more powerful than ours; and if that is the case, it must throw the borders of his domain so much the further back by approaching them to us, and at the same time retrench the circumference of the sun.

I cannot avoid presuming, that in this great number of fixed stars, which are all so many suns, there are some greater and others smaller than ours; others more or less luminous, some nearer, which are represented to us by those stars called by astronomers, stars of the first magnitude, and many others more remote, which for that reason appear to us smaller. The stars called nebulous seem to want light and fire, and to be only half lighted; those which appear and disappear alternately are, perhaps, of a form flattened by the violence of the centrifugal force in their motion of rotation, and are perceiveable only when they are in the full, disappearing when they are sideways. In this grand order of things, and in the nature of the stars, there are the same varieties, and the same differences, in number, size, space, motion, form, and duration; the same relation, the same degrees, and the same connection, as are found in all the other orders of the creation.

Each of the suns being endowed like ours, and like all matter, with an attractive power, which extends to an indefinite distance, and decreases, as the space increases, analogy leads us to imagine that within each of their spheres there exists a great number of opaque bodies, planets, or comets, which circulate round them, but which being much smaller than the suns which serve them for heat, they are beyond the reach of our sight.

It might be imagined that comets pass from one system to the other, and that if they happened to approach the confines of the two empires they would be attracted by the preponderating power, and forced to obey the laws of a new master. But, by the immensity of space which is beyond the aphelion of our comets, it appears that the Sovereign Ruler has separated each system by immense desarts, a thousand and a thousand times larger than all the extent of known spaces. These desarts, which numbers cannot fathom the depth of, are external and invincible barriers, that all the powers of created nature cannot surmount. To form a communication from one system to the other, and for the subjects of one to pass into the other, it would be requisite that the centre was not immoveable, for the sun, the head of the system, changing place, would draw with it in its course all the bodies which depend thereon, and hence might approach and invade another demesne. If its route were directed towards a weaker star, it would commence by carrying off the subjects of its most distant provinces, afterwards those more interior, and would oblige them all to increase its train by revolving round it; and its neighbour thus deprived of its subjects, no longer having planets nor comets, would lose both its light and fire, which their motion alone can excite and support; hence this detached star, being no longer maintained in its place by the equilibrium of its forces, would be obliged to change nutrition, by changing nature, and becoming an obscure body, would, like the rest, obey the power of the conqueror, whose fire would increase in proportion to the number of its conquests.

For what can be said on the nature of the sun but that it is a body of prodigious volume, an enormous mass of matter penetrated by fire, which appears to subsist without aliment, and which resembles a metal or a solid body in incandescence? And from whence can this constant state of incandescence, this continually renewed production of fire proceed, whose consumption does not appear to be supported by any aliment, and whose deperdition is at least insensible, although constant for such a great number of years? Is there, or can there be, any other cause of the production of this permanent fire, but the rapid motion from the strong pressure of all bodies, which revolve round this common heat, and which heats and sets fire to it, like a wheel rapidly turned round its axis? The pressure, which they exercise by virtue of their weight is equivalent to the friction, and even more powerful, because this pressure is a penetrating power, which not only rubs the external surface but all the internal parts of the mass: the rapidity of their motion is so great that the friction acquires a force almost infinite, and consequently sets the whole mass of the axis in a state of incandescence, of light, of heat, and of fire, which hence has no need of aliment to be supported, and which, in spite of the deperdition each day made by the emission of light, may remain for ever without any sensible alteration, other suns rendering as much light to ours as it sends to them, and no part of the smallest atom of fire, or any other matter, being lost in a system where all is attracted.

If from this sketch of the great table of the heavens, and in which I have only attempted to represent to myself the proportion of the spaces, and that of the motion of bodies which travel over them; if from this point of view, to which I only raised myself to see how greatly nature must be multiplied in the different regions of the universe, we descend to that proportion of space which we are better acquainted with, and in which the sun exercises its power, we shall discover, that although it governs all bodies therein, it, nevertheless, has not the power of vivifying them, nor even that of supporting life and vegetation.

Mercury, which is the nearest to the sun, nevertheless receives only a heat 400 times stronger than that of the earth, and this heat, so far from being burning, as it has always been supposed, would not be strong enough of itself to support animated nature, for the actual heat of the sun on the earth being only 1/50 part of the heat of the terrestrial globe, that of the sun on Mercury consequently is only 1/8 part of the actual heat of the earth. Now if 7/8 parts were subtracted from the heat which is at present the temperature of the earth, it is certain animated nature would be checked, if not entirely extinguished. Since the sun alone cannot maintain organised nature in the nearest planet, how much more aid must it require to animate those at a greater distance? To Venus it only sends a heat 2/50 times stronger than that it sends to the earth, which instead of being strong enough to support animated nature, would not certainly suffice to maintain the liquidity of water, nor perhaps even the fluidity of air, since our actual temperature would be refrigerated to 2/49, which is very near the term 1/25 we have given as the external limit of the slightest heat, relative to living nature. And with respect to Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and all their satellites, the quantity of heat which the sun sends to them, in comparison with that which is necessary for the support of nature, which may be looked upon as of little effect, especially in the two larger planets, which, nevertheless, appear to be the essential objects of the solar system.

All the planets, therefore, have always been volumes (as large as useless) of matter more than dead, profoundly frozen, and consequently places uninhabited and uninhabitable for ever, if they do not include within themselves treasures of heat much superior to what they receive from the sun. The heat which our globe possesses of itself, and which is 50 times greater than that which comes to it from the sun, is, in fact, the treasure of nature, the true fund which animates us as well as every being: it is this internal heat of the earth which causes all things to germinate and to develope; it is that which constitutes the element of fire, properly called an element, which alone gives motion to other elements, and which if it was reduced to 1/20 could not conquer their resistance, but would itself fall into an inertia. Now this element, this sole active power, which may render the air fluid, the water liquid, and the earth penetrable, might it not have been given to the terrestrial globe alone? Does analogy permit us to doubt that the other planets do not likewise contain a quantity of heat, which belongs to them alone, and which must render them capable of receiving and supporting living nature? Is it not greater and more worthy the idea we ought to have of the Creator, to suppose that there every where exists beings who acknowledge his power and celebrate his glory, than to depopulate all the universe, excepting the earth, and to despoil it of all beings, by reducing it to a profound solitude, in which we should only find a desart space, and frightful masses of inanimate matter.