полная версия

полная версияRuins of Ancient Cities (Vol. 1 of 2)

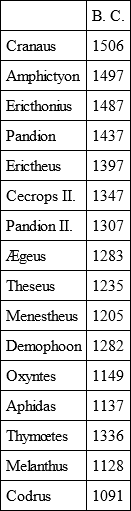

It was governed by seventeen kings, in the following order: —

After a reign of fifty years, Cecrops was succeeded by

The history of the first twelve monarchs is, for the most part, fabulous.

Athens was founded by Cecrops, who led a colony out of Egypt, and built twelve towns, of which he composed a kingdom.

Amphictyon, the third king of Athens, procured a confederacy between twelve nations, who met every year at Thermopylæ, there to consult over their affairs in general, as also upon those of each nation in particular. This convention was called the assembly of the Amphictyons.

The reign of Ægeus is remarkable for the Argonautic expedition, the war of Minos, and the story of Theseus and Ariadne.

Ægeus was succeeded by his son, Theseus, whose exploits belong more to fable than to history.

The last king was Codrus, who devoted himself to die for his people.

After Codrus, the title of king was extinguished among the Athenians: his son was set at the head of the commonwealth, with the title of Archon, which after a time was declared to be an annual office.

After this Draco was allowed to legislate, and then Solon. The laws of the former were so severe, that they were said to be written in blood. Those of the latter were of a different character. Pisistratus acquired ascendancy; became a despot, and was assassinated: whereon the Athenians recovered their liberties, and Hippias, the son of Pisistratus, in vain attempted to re-establish a tyranny. The Athenians, sometime after, burnt Sardis, a city of the Persians, in conjunction with the Ionians; and, to revenge this, Darius invaded Greece, but was conquered at Marathon by Miltiades.

Xerxes soon after invaded Attica, and the Athenians having taken to their "wooden walls," their city was burnt to the ground.

After the victory, gained over the Persians at Salamis, the Athenians returned to their city, but were obliged to abandon it again; Mardonius having wasted and destroyed every thing in its neighbourhood. They returned to it soon after their victory at Platæa. Their first care, after returning to their city, was to rebuild their walls. This measure was opposed by the Lacedemonians, under the pretence of its being contrary to the interest of Greece, that there should be strong places beyond the isthmus. Their real motive, however, was suspected to be an aversion to the rising greatness of the Athenians. Themistocles conducted himself with great art in this matter48. He got himself appointed ambassador to Sparta; and before setting out he caused all the citizens, of every age and sex, to apply themselves to the task of building the walls, making use of any materials within their reach. Fragments of houses, temples, and other buildings, were accordingly employed, producing a grotesque appearance, which remained to the days of Plutarch. He then set out for Sparta; but, on various pretences, declined entering on his commission, till he had received intelligence that the work he had set on foot was nearly completed. He then went boldly to the Lacedemonian senate, declared what had been done, and justified it, not only by natural right of the Athenians to provide for their own defence, but by the advantage of opposing such an obstacle to the progress of the barbarians. The Lacedemonians, sensible of the justice of this argument, and seeing that remonstrance would now avail nothing, were fain to acquiesce.

No city in the world can boast, in such a short space of time, of such a number of illustrious citizens, equally celebrated for their humanity, learning, and military abilities. Some years after the Persian defeat, Athens was visited by a very terrible calamity, insomuch that its ravages were like what had never been before known. This was a plague. We now adopt the language of Rollin. "It is related, that this scourge began in Ethiopia, whence it descended into Egypt, from thence spread over Libya, and a great part of Persia; and at last broke at once like a flood upon Athens. Thucydides, who himself was seized with that deadly disease, has described very minutely the several circumstances and symptoms of it; in order, says he, that a faithful and exact relation of this calamity may serve as an instruction to posterity, in case the like should ever happen. This pestilence baffled the utmost efforts of art; the most robust constitutions were unable to withstand its attacks; and the greatest care and skill of the physicians were a feeble help to those who were infected. The instant a person was seized, he was struck with despair, which quite disabled him from attempting a cure. The assistance that was given them was ineffectual, and proved mortal to all such of their relations as had the courage to approach them. The prodigious quantity of baggage, which had been removed out of the country into the city, proved very noxious. Most of the inhabitants, for want of lodging, lived in little cottages, in which they could scarcely breathe, during the raging heat of the summer; so that they were seen either piled one upon the other, the dead as well as those who were dying, or else crawling through the streets; or lying along by the side of fountains, to which they had dragged themselves, to quench the raging thirst which consumed them. The very temples were filled with dead bodies, and every part of the city exhibited a dreadful image of death; without the least remedy for the present, or the least hopes with regard to futurity.

"The plague, before it spread into Attica, had, as we have before stated, made wild havoc in Persia. Artaxerxes, who had been informed of the mighty reputation of Hippocrates of Cos, the greatest physician of that or any other age, caused his governors to write to him, to invite him into his dominions, in order that he might prescribe for those who were infected. The king made him the most advantageous offers; setting no bounds to his rewards on the side of interest, and, with regard to honours, promising to make him equal with the most considerable persons in his court. This great physician sent no other answer but this: – that he was free from either wants or desires; and he owed all his cares to his fellow-citizens and countrymen; and was under no obligation to the declared enemies of Greece. – Kings are not used to denials. Artaxerxes, therefore, in the highest transports of rage, sent to the city of Cos, the native place of Hippocrates, and where he was at that time; commanding them to deliver up to him that insolent wretch, in order that he might be brought to condign punishment; and threatening, in case they refused, to lay waste their city and island in such a manner, that not the least footsteps of it should remain. However, the inhabitants of Cos were not under the least terror. They made answer, that the menaces of Darius and Xerxes had not been able to prevail with them to give them earth and water, or to obey their orders; that Artaxerxes' threats would be equally impotent; that, let what would be the consequence, they would never give up their fellow citizens; and that they depended upon the protection of the gods.

"Hippocrates had said in one of his letters, that he owed himself entirely to his country. And, indeed, the instant he was sent for to Athens, he went thither, and did not once stir out of the city till the plague had ceased. He devoted himself entirely to the service of the sick; and, to multiply himself, as it were, he sent several of his disciples into all parts of the country, after having instructed them in what manner to treat their patients. The Athenians were struck with the deepest sense of gratitude for this generous care. They therefore ordained, by a public decree, that Hippocrates should be initiated in the most exalted mysteries, in the same manner as Hercules the son of Jupiter; that a crown of gold should be presented him, of the value of a thousand staters49, and that the decree by which it was granted him, should be read aloud by a herald in the public games, on the solemn festival of Panathenæa: that the freedom of the city should be given him, and himself be maintained at the public charge, in the Prytaneum all his lifetime, in case he thought proper: in fine, that the children of all the people of Cos, whose city had given birth to so great a man, might be maintained and brought up in Athens, in the same manner."

In the time of Agis and Pausanias, kings of Lacedemonia, Lysander was sent to besiege Athens. He arrived, therefore, at the Piræus, with a fleet of one hundred and fifty sail, and prevented all other ships from coming in or going out. The Athenians, besieged by land and sea, without provisions, ships, hope of relief, or any resources, sent deputies to Agis, to propose a treaty with Sparta, upon condition of abandoning all their possessions, the city and port only excepted. He referred the deputies to Lacedemon, as not being empowered to treat with them. When they arrived at Salasia, upon the frontier of Sparta, and had made known their commission to the Ephori, they were ordered to retire, and to come with other proposals, if they expected a peace. The Ephori had demanded, "that one thousand two hundred paces of the wall on each side of the Piræus should he demolished;" but an Athenian, for venturing to advise a compliance, was sent to prison, and prohibition made against proposing any thing of that kind for the future.

The Corinthians and several other allies, especially the Thebans, insisted that it was absolutely necessary to destroy the city without hearkening any further to a treaty. But the Lacedemonians, preferring the glory and safety of Greece to their own grandeur, made answer, that they would never be reproached with having destroyed a city that had rendered such great services to all Greece; the remembrance of which ought to have much greater weight with the allies than the remembrance of private injuries received from it. A peace was, therefore, concluded under these conditions: – "that the fortifications of the Piræus, with the long wall that joined that port to the city, should be demolished; that the Athenians should deliver up all their galleys, twelve only excepted; that they should abandon all the cities they had seized, and content themselves with their own lands and country." The deputies, on their return, were surrounded by an innumerable throng of people, who apprehended that nothing had been concluded; for they were not able to hold out any longer, such multitudes dying of famine. The next day they reported the success of their negociation; the treaty was ratified, and Lysander, followed by the exiles, entered the port. It was on the very day the Athenians had formerly gained the famous battle of Salamis. He caused the works to be demolished to the sound of flutes and trumpets, as if all Greece had that day regained its liberty. Thus ended the Peloponnesian war, after having continued during the space of twenty-seven years.

The walls, thus demolished, were rebuilt by Conon. He did more; he restored Athens to its former splendour, and rendered it more formidable to its enemies than it had ever been before.

Philip50 having gained the battle of Cheronæa, Greece, and above all, Athens, received a blow from which she never recovered. It was generally expected, that Philip would avail himself of this opportunity of entirely crushing his inveterate enemy. That prudent prince, however, foresaw that powerful obstacles were yet to be encountered, and that there was still a spirit in the Athenian people which might render it difficult to hold them in subjection. It would appear, also, says an elegant writer, as if the genius and fame of Athens had, in the hour of her calamity, thrown a shield over her: for Philip is reported to have said, "Have I done so much for glory, and shall I destroy the theatre of that glory?" A treaty, in consequence, was entered into; and thus the Athenians, though reluctant to exist by Philip's clemency, were permitted to retain the whole Attic territory.

The number of men able to bear arms at Athens, in the reign of Cecrops, was computed at twenty thousand; and there appears to have been no considerable augmentation in the more civilised age of Pericles; but in the time of Demetrius Phalareus, there were found twenty-one thousand citizens, ten thousand foreigners, and forty thousand slaves.

Philip51, son of Demetrius of Macedon, seems to have been one of the most inveterate enemies by whom Athens was ever ravaged. With unsparing cruelty he destroyed almost every thing which had either escaped the Persian invaders, or which had been erected after their final expulsion. Livy tells us, that, not content with burning and destroying the temples of the gods, he ordered that the very stones should be broken into small pieces, that they might no longer serve to repair the buildings; and Diodorus Siculus asserts, that even the inviolability of the sepulchres could not command his respect, or repress his violence.

Athens, however, still recovered some portion of its power; for when Sylla arrived before the Piræus, he found the walls to be sixty feet high, and entirely of hewn stone. The work was very strong, and had been raised by order of Pericles in the Peloponnesian war: when, the hopes of victory depending solely upon this port, he had fortified it to the utmost of his power.

The height of the walls did not deter Sylla. He employed all sorts of engines in battering them, and made continual assaults. He spared neither danger, attacks, nor expense, to hasten the conclusion of the war. Without enumerating the rest of the warlike stores and equipage, twenty thousand mules were perpetually employed in working the machines only. Wood happening to fall short, from the great consumption made of it in the machines, which were often either broken or spoiled by the vast weight they carried, or burned by the enemy, he did not spare the sacred groves. He cut down the trees in the walks of the Academy and Lycæum, which were the finest and best planted in the suburbs, and caused the high walls that joined the port to the city to be demolished, in order to make use of the ruins in erecting his works, and carrying on his operations.

Notwithstanding all disadvantages, the Athenians defended themselves like lions. They found means either to burn most of the machines erected against the walls, or by undermining them, to throw them down and break them to pieces. The Romans, on their side, behaved with no less vigour. Sylla, discouraged by so obstinate a defence, resolved to attack the Piræus no longer, and confined himself to reduce the place by famine. The city was now at the last extremity; a bushel of barley having been sold in it for a thousand drachms (about 25l. sterling). In the midst of the public misery, the governor, who was a lieutenant of Mithridates, passed his days and nights in debauch. The senators and priests went to throw themselves at his feet, conjuring him to have pity on the city, and to obtain a capitulation from Sylla; he dispersed them with arrow-shot, and in that manner drove them from his presence.

He did not demand a cessation of arms, nor send deputies to Sylla, till reduced to the last extremity. As those deputies made no proposals, and asked nothing of him to the purpose, but ran on in praising and extolling Theseus, Eumolpus, and the exploits of the Athenians against the Medes, Sylla was tired of their discourse, and interrupted them by saying, – "Gentlemen haranguers, you may go back again, and keep your rhetorical flourishes to yourselves. For my part, I was not sent to Athens to be informed of your ancient prowess, but to chastise your modern revolt."

During this audience, some spies having entered the city, overheard by chance some old men talking of the quarter called Ceramicus (the public place at Athens), and blaming the tyrant exceedingly for not guarding a certain part of the wall that was the only place by which the enemy could scale the walls. At their return into the camp, they related what they heard to Sylla. The parley had been to no purpose. Sylla did not neglect the intelligence given him. The next night he went in person to take a view of the place; and finding the wall actually accessible, he ordered ladders to be raised against it, began the attack there, and, having made himself master of the wall, after a weak resistance, entered the city. He would not suffer it to be set on fire, but abandoned it to be plundered by his soldiers, who, in several houses, found human flesh, which had been dressed to be eaten. A dreadful slaughter ensued. The next day all the slaves were sold by auction, and liberty was granted to the citizens who had escaped the swords of the soldiers, who were a very small number. He besieged the citadel the same day, where Aristion and those who had taken refuge there, were soon so much reduced by famine, that they were forced to surrender themselves. The tyrant, his guards, and all who had been in any office under him, were put to death. Some ten days after, Sylla made himself master of the Piæaus, and burned all its fortifications.

The reputation for learning, military valour, and polished elegance, which Athens enjoyed during the splendid administration of Pericles, was tarnished by the corruption which that celebrated person introduced. Prosperity was the forerunner of luxury and universal dissipation; every delicacy was drawn from distant nations; the wines of Cyprus, and the snows of Thrace, garlands of roses, perfumes, and a thousand arts of buffoonery, which disgraced a Persian court, were introduced; instead of the coarse meals, the herbs and plain bread, which the laws of Solon had recommended, and which had nourished the heroes of Marathon and Salamis.

Sylla's assault was the final termination of the power and greatness of Athens; she became a portion of the Roman empire; but in the reign of Hadrian and the Antonines, she resumed, at least in outward appearance, no small portion of her former splendour. Hadrian built several temples, and, above all, he finished that of Jupiter Olympius, the work of successive kings, and one of the greatest productions of human art. He founded, also, a splendid library; and bestowed so many privileges, that an inscription, placed on one of the gates, declared Athens to be no longer the city of Theseus, but of Hadrian. In what manner it was regarded too in the time of Trajan, may be gathered from Pliny's letter to a person named Maximus, who was sent thither as governor.

"Remember," said he, "that you are going to visit Achaia, the proper and true Greece; that you are appointed to govern a state of free cities, who have maintained liberty by their valour. Take not away any thing of their privileges, their dignity; no, nor yet of their presumption; but consider it is a country that hath of long time given laws, and received none; that it is to Athens thou goest, where it would be thought a barbarous cruelty in thee to deprive them of that shadow and name of liberty which still remaineth to them."

The Antonines trod in the steps of Hadrian. Under them Herodes Atticus devoted an immense fortune to the embellishment of the city and the promotion of learning.

But when the Roman world felt the wand of adversity, and her power began to decline, Athens felt her share; she had enjoyed a long respite from foreign war, but in the reign of Arcadius and Honorius a dreadful tempest burst upon her.

Alaric, after over-running the rest of Greece, advanced into Attica, and found Athens without any power of defence. The whole country was converted into a desert; but it seems uncertain, whether he plundered the city, or whether he accepted the greater part of its wealth as a ransom. Certain, however, it is, that it suffered severely, and a contemporary compared it to the mere skin of a slaughtered victim.

It is reported that, during their stay in the city, the barbarians, having collected all the libraries of Athens, were preparing to burn them; but one of their number diverted them from their design, by suggesting the propriety of leaving to their enemies what appeared to be the most effectual instrument for cherishing and promoting their unwarlike spirit.

After the devastations of Alaric, and, still more, after the shutting up of her schools, Athens ceased almost entirely to attract the attention of mankind. These schools were suppressed by an edict of Justinian; an edict which excited great grief and indignation among the few remaining votaries of Grecian science and superstition. Seven friends and philosophers,52 who dissented from the religion of their sovereign, resolved to seek in a foreign land the freedom of which they were deprived in their native country. Accordingly, the seven sages sought an asylum in Persia, under the protection of Chosroes; but, disgusted and disappointed, they hastily returned, and declared that they had rather die on the borders of the empire than enjoy the wealth and favour of the barbarian. These associates ended their lives in peace and obscurity; and as they left no disciples, they terminate the long list of philosophers who may be justly praised, notwithstanding their defects, as the wisest and most virtuous of their times53.

After the taking of Constantinople by the Latins, in the beginning of the thirteenth century, the western powers began to view Greece as an object of ambition. In the division of the Greek empire, which they made among themselves, Greece and Macedonia fell to the share of the Marquis of Montferrat, who bestowed Athens and Thebes on one of his followers, named Otho de la Roche. This prince reigned with the title of Duke of Athens, which remained for a considerable time54.

It was afterwards seized by a powerful Florentine family, named Acciaioli, one of whom sold it to the Venetians; but his son seized it again, and it remained in that family till A. D. 1455, when it surrendered to Omar, a general of Mahomet II., and thus formed one of the two hundred cities which that prince took from the Christians. He settled a colony in it, and incorporated it completely with the Turkish empire. What has occurred of late years has not been embodied in any authentic history; but the consequences of the tumults of Greece may be in some degree imagined, from what is stated by a recent traveller in regard to Athens55. "When I sallied forth to explore the wonders of Athens, alas! they were no longer to be seen. The once proud city of marble was literally a mass of ruins – the inglorious ruins of mud-houses and wretched mosques forming in all quarters such indistinguishable piles, that in going about I was wholly unable to fix upon any peculiarities of streets or buildings, by which I might know my way from one part of the capital to another. With the exception of the remains of the Forum, the temple of Theseus, which is still in excellent preservation, the celebrated columns of the temple of Jupiter Olympius, and the Parthenon, nothing now exists at Athens of all the splendid edifices with which it was so profusely decorated in the days of its glory."

It has been well observed, that, associated in the youthful mind with all that is noble in patriotism, exalted in wisdom, excelling in art, elegant in literature, luminous in science, persuasive in eloquence, and heroic in action, the beautiful country of Greece, and its inhabitants, must, under every circumstance, even of degradation, be an interesting object of study. "We can all feel, or imagine," says Lord Byron, "the regret with which the ruins of cities, once the capital of empires, are beheld. But never did the littleness of man, and the vanity of his very best virtues, of patriotism to exalt and of valour to defend his country, appear more conspicuous than in the record of what Athens once was, and the certainty of what she now is."

The former state of Athens is thus described by Barthelemy. "There is not a city in Greece which presents so vast a number of public buildings and monuments as Athens. Edifices, venerable for their antiquity, or admirable for their elegance, raise their majestic heads on all sides. Masterpieces of sculpture are extremely numerous, even in the public places, and concur with the finest productions of the pencil to embellish the porticoes of temples. Here every thing speaks to the eyes of the attentive spectator."

To describe Athens entire would be to fill a volume. We shall, therefore, only give an account of the chief monuments of antiquity as they existed till very lately; the rest, as they give one little or no sort of idea of their ancient magnificence, were better omitted than mentioned.