полная версия

полная версияRuins of Ancient Cities (Vol. 1 of 2)

196

Jose.

197

Thucydides; Rollin; Wheler; Dodwell; Williams.

198

Rollin.

199

Rollin.

200

Demens! qui nimbos et non imitabile fulmen,Ære et cornipedum cursu simulâretsquorum. – Virg.201

Kennet.

202

History of the Turks.

203

Dodwell.

204

Herodotus; Pliny the Nat.; Du Loir; Rollin; Kennet; Knowles; Wheler; Chandler; Barthelemy; Stuart; Dodwell; Quin; Turner.

205

The story of the maid of Corinth may be found in Pliny, lib. xxxv.; and in Athenagoras, with this additional circumstance, that the lover, while his outlines were taken, is described to have been asleep.

206

Gibbon.

207

The royal canal (Nahar-Malcha) might be successively restored, altered, divided, &c. (Cellarius Geograph. Antiq. tom. ii. p. 453): and these changes may serve to explain the seeming contradictions of antiquity. In the time of Julian, it must have fallen into the Euphrates, below Ctesiphon.

208

These works were erected by Orodes, one of the Arsacidæan kings.

209

"I suspect," says Mr. Gibbon, "that the extravagant numbers of Elmacin may be the error, not of the text, but of the version. The best translators from the Greek, for instance, I find to be very poor arithmeticians."

210

Selman the Pure.

211

Rollin; Gibbon; Porter; Buckingham.

212

Williams.

213

Dodwell.

214

Rollin; Barthélemi; Chandler; Clarke; Dodwell; Williams.

215

In Judith, Dejoces is called Arphaxad: – "1. In the twelfth of the reign of Nabuchodonosor, who reigned in Nineveh, the great city; in the days of Arphaxad, which reigned over the Medes in Ecbatana.

2. And built in Ecbatana walls round about of stones hewn, three cubits broad and six cubits long, and made the height of the walls seventy cubits, and the breadth thereof fifty cubits.

3. And set the towers thereof upon the gates of it, an hundred cubits high, and the breadth thereof in the foundation thereof three score cubits.

4. And he made the gates thereof, even gates that were raised to the height of seventy cubits, and the breadth of them was forty cubits, for the going forth of his mighty armies, and for the setting in array of his footmen."

216

It is said, in Esther, that Ahasuerus reigned over one hundred and twenty-seven princes; from India to Ethiopia.

217

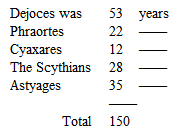

According to Herodotus, the reign of

218

Some authors have made a strange mistake: they have confused this city with that of the same name in Syria, at the foot of Mount Carmel; and still more often with that which was called the "City of the Magi."

219

Lib. x. 24.

220

Clio, 98.

221

Ecbatana was taken by Nadir Shah. Nadir marched against the Turks as soon as his troops were refreshed from the fatigues they had endured in the pursuit of the Afghauns. He encountered the force of two Turkish pachas on the plains of Hameden, overthrew them, and made himself master, not only of that city, but of all the country in the vicinity. – Meerza Mehdy's Hist. Sir William Jones's works, vol. v. 112; Malcolm's Hist. of Persia, vol. ii. 51. 4to.

222

"This custom," says Mr. Morier, "which I had never seen in any other part of Asia, forcibly struck me as a most happy illustration of our Saviour's parable of the labourer in the vineyard; particularly when passing by the same place, late in the day, we still found others standing idle, and remembered his words, 'Why stand ye here all the day idle?' as most applicable to their situation; for in putting the question to them, they answered 'Because no one has hired us.'"

223

Lib. x. c. 24.

224

"The habitations of the people here (at Hameden) were equally mean as those of the villages through which we had passed before. The occupiers of these last resembled, very strongly, the African Arabs, or Moors, and also the mixed race of Egypt, in their physiognomy, complexion, and dress. The reception, given by these villagers to my Tartar companions, was like that of the most abject slaves to a powerful master; and the manner in which the yellow-crowned courtiers of the Sublime Porte treated their entertainers in return, was quite as much in the spirit of the despotic sultan whom they served." —Buckingham's Travels in Mesopotamia, vol. ii. p. 18.

225

Herodotus; Diodorus Siculus; Plutarch; Arrian; Quintus Curtius; Rollin; Rennell; Morier; Sir R. Ker Porter; Buckingham.

226

Rollin.

227

Dodwell.

228

Rollin; Barthelemy; Wheler; Chandler; Sandwich; Clarke; Hobhouse; Dodwell.

229

Gillies.

230

Chandler.

231

Pausanias; Plutarch; Barthelemy; Chandler; Dodwell; Rees; Gillies.

232

Breadth scarcely anywhere exceeding forty miles.

233

The others were, Miletus, Myus, Lebedos, Colophon, Priene, Teos, Erythræ, Phocæa, Clazomenæ, Chios, and Samos.

234

Polyen. Strat. vi.

235

Diana was the patroness of all women in labour, as well as of the children born.

236

The Ephesians have a very wise law relative to the construction of public edifices. The architect whose plan is chosen enters into a bond, by which he engages all his property. If he exactly fulfils the condition of his agreement, honours are decreed him; if the expense exceeds the sum stipulated only by one quarter, the surplus is paid from the public treasury; but if it amounts to more, the property of the architect is taken to pay the remainder. – Barthelemy, vol. v. 394, 5; from Vitruvius Præf., lib. x. 203.

237

We often see this temple represented upon medals with the figure of Diana. It is never charged with more than eight pillars; and sometimes only with six, four, and now and then only with two.

238

The columns being sixty feet high, the diameter, according to rule, must be six feet eight inches; that is, one-ninth part. Thus, every column would contain one hundred and ten tons of marble, besides base and capital! – Wren's Parentalia, p. 361.

239

Mithridates caused 150,000 Romans in Asia to be massacred in one day

240

Hist. August, p. 178; Jornandes, c. 20.

241

Strabo, 1. xiv. 640; Vitruvius, 1. i. c. 1; Præf. 1. vii.; Tacitus Annal. iii. 61; Plin. Nat. Hist. xxxvi. 14.

242

The length of St. Peter's is 840 Roman palms; each palm is very little short of nine English inches.

243

They offered no sacrifices to the Grecian gods.

244

Acts xx. 31.

245

Acts xix. 11; 1 Cor. xv. 9.

246

Acts xx. 19.

247

Ch. ii.

248

Revett's MS. notes.

249

On this passage Mr. Revett has left the following observation in a MS. note: "Upon what authority? Vitruvius, though he relates the story, does not give us the name of the mountain on which it happened. If mount Prion consists of white marble, it is very extraordinary it was not discovered sooner; part of the mountain being included in the city."

250

Diodorus Siculus; Vitruvius; Plin. Nat. Hist.; Plutarch; Polyænus; Wren's Parentalia; Barthelemy; Gibbon; Wheler; Chandler; Revett; Clarke; Hobhouse; Brewster; Rees.

251

Seetzen; Burckhardt; Irby; Robinson.

252

From a work published in 1778.

253

Anon.

254

Hippolyto de Jose; Swinburne; Wright; Murphy; Washington Irving.

255

Lempriere.

256

Morritt.

257

Turner.

258

Turner; Clarke.

259

Barthelemy; Lempriere; Rees; Mitford; Clarke; Walpole; Morritt; Turner.

260

Rollin.

261

Bossuet; Rollin; Encyclop. Metropolitana; Denon.

262

Eustace.

263

Dionysius of Halicarnassus makes it sixty years before the fall of Troy; or 1342 B. C.

264

Chambers.

265

Chambers.

266

He was then only eighteen.

267

The death of this celebrated naturalist was probably occasioned by carbonic acid gas. This noxious vapour must have been generated to a great extent during the eruption. It is heavier than common air, and, of course, occupies in greater proportion the substrata of that circumambient fluid. The supposition is greatly strengthened by the fact, that the old philosopher had lain down to rest; but the flames approaching him, he was compelled to rise, assisted by two servants, which he had no sooner done than he fell down dead.

268

It is a remarkable circumstance that some naturalists walking amid the flowers, on the summit of Vesuvius, the very day before this eruption, were discussing whether this mountain was a volcano.

269

Gandy, 53.

270

Mons. Du Theil.

271

Rees.

272

Brewster.

273

Ibid.

274

Brewster.

275

Brewster.

276

Brewster, 741.

277

Ibid, 740.

278

Rees.

279

Dupaty.

280

Brewster.

281

The letters in the smaller type were inserted by Ciampitti; as those he considered appropriate for filling up passages which could not be deciphered.

282

Pliny the younger; Encycl. Rees, Metrop.; Brewster; Dupaty; Eustace.

283

Plin. v. c. 26. Ptolem. v. c. 15.

284

Ptolemy; Pliny; Pococke; Chandler.

285

This was an epithet given to Crete, from the 100 cities which it once contained: also to Thebes in Egypt, on account of its 100 gates. The territory of Laconia had the same epithet for the same reason that Thebes had; and it was the custom of these 100 cities to sacrifice a hecatomb every year.

286

Sir John Malcolm.

287

The boundaries of Iran, which Europeans call Persia, have undergone many changes. The limits of the kingdom in its most prosperous periods may, however, be easily described. The Persian Gulf, or Indian Ocean, to the south; the Indies and the Oxus to the east and north-east; the Caspian Sea and Mount Caucasus to the north; and the river Euphrates to the west. The most striking features of this extensive country, are numerous chains of mountains, and large tracts of desert; amid which are interspersed beautiful valleys and rich pasture lands. – Sir John Malcolm.

288

I conquered the city of Isfahan, and I trusted in the people of Isfahan, and I delivered the cattle in their hands. And they rebelled; and the darogah whom I had placed over them they slew, with 3000 of the soldiers. And I also commanded that a general slaughter should be made of the people of Isfahan. – Timour's Institutes, p. 119. Malcolm's Hist. Persia, vol. i. 461.

289

Porter.

290

Lett. ii. 1. 3.

291

vii. 273, 486. viii. 2, 144.

292

Sir John Kinneir says of this causeway: "It is in length about 300 miles. The pavement is now nearly in the same condition as it was in the time of Hanway; being perfect in many places, although it has hardly ever been repaired."

293

At one time a horse's carcase sold for one thousand crowns.

294

Malcolm, Hist. Persia from Murza Mahdy.

295

The horrors of this siege, equal to any recorded in ancient history, have been described by the Polish Jesuit Krurinski, who personally witnessed them (see his History of the Revolution of Persia, published by Père du Cerceau); and they are noticed in the "Histoire de Perse depuis le commencement de ce siècle" of M. la Marnya Clairac, on authorities that cannot be disputed. – Ouseley's Trav.

296

Geog. Mem. of Persia.

297

Morier.

298

Malte-Brun.

299

Job, chap. xv. ver. 28.

300

Ferdousi; Ebn Hakekl; Della Valle; Chardin; Kinneir; Porter; Malcolm; Malte-Brun; Ouseley.

301

Hippolito de Jose.

302

From the time that Solomon, by means of his temple, had made Jerusalem the common place of worship to all Israel, it was distinguished from the rest of the cities by the epithet Holy, and in the Old Testament was called Air Hakkodesh, i. e., the city of holiness, or the holy city. It bore this title upon the coins, and the shekel was inscribed Jerusalem Kedusha, i. e., Jerusalem the Holy. At length Jerusalem, for brevity's sake, was omitted, and only Kedusha reserved. The Syriac being the prevailing language in Herodotus's time, Kedusha, by a change in that dialect of sh into th, was made Kedutha; and Herodotus, giving it a Greek termination, it was writ Κάδυτις, or Cadytis. – Prideaux's Connexion of the Old and New Testament, vol. i. part i. p. 80, 81, 8vo. edit.

303

And Joshua smote all the country of the hills, and of the south, and of the vale, and of the springs, and all their kings; he left none remaining; but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded. – Joshua, ch. x. ver. 40.

304

– The emotions which filled the minds of those who witnessed the laying of the foundation of the temple were strangely mingled. All gave thanks to the Lord; and the multitude shouted with a great shout when the foundations were laid; but, "many of the priests and Levites, and chief of the fathers, who were ancient men, that had seen the first house, when the foundation of this house was laid before their eyes, wept with a loud voice." – Ezra, iii. 12.

305

Besides this, he built another temple.

306

Some have thought that this description, which is from Josephus, applies rather to the temple of Herod.

307

It is remarkable that the sum mentioned is equal to the British national debt.

308

"Because thou servedst not the Lord thy God with joyfulness, and with gladness of heart, for the abundance of all things; therefore shalt thou serve thine enemies which the Lord shall send against thee, in hunger, and in thirst, and in nakedness, and in want of all things: and he shall put a yoke of iron upon thy neck, until he have destroyed thee. The Lord shall bring a nation against thee from far, from the end of the earth, as swift as the eagle flieth; a nation whose tongue thou shalt not understand; a nation of fierce countenance, which shall not regard the person of the old, nor show favour to the young: and he shall eat the fruit of thy cattle, and the fruit of thy land, until thou be destroyed: which also shall not leave thee either corn, wine, or oil, or the increase of thy kine, or flocks of thy sheep, until he have destroyed thee. And he shall besiege thee in all thy gates, until thy high and fenced walls come down, wherein thou trustedst, throughout all thy land: and he shall besiege thee in all thy gates throughout all thy land, which the Lord thy God hath given thee. And thou shalt eat the fruit of thine own body, the flesh of thy sons and of thy daughters, which the Lord thy God hath given thee, in the siege, and in the straitness, wherewith thine enemies shall distress thee: so that the man that is tender among you and very delicate, his eye shall be evil toward his brother, and toward the wife of his bosom, and toward the remnant of his children which he shall leave: so that he will not give to any of them of the flesh of his children whom he shall eat: because he hath nothing left him in the siege, and in the straitness, wherewith thine enemies shall distress thee in all thy gates. The tender and delicate woman among you, which would not adventure to set the sole of her foot upon the ground for delicateness and tenderness, her eye shall be evil toward the husband of her bosom, and toward her son, and toward her daughter, and toward her children which she shall bear: for she shall eat them for want of all things secretly in the siege and straitness wherewith thine enemy shall distress thee in thy gates." – Deut. xxviii. 47-57.

309

Deut. xxix. 22, 24, 27.

310

Robinson.

311

Buckingham.

312

The patriarch, says an accomplished traveller, makes his appearance in a flowing vest of silk, instead of a monkish habit, and every thing around him bears the character of Eastern magnificence. He receives his visitors in regal stateliness; sitting among clouds of incense, and regaling them with all the luxuriance of a Persian court.

313

Dr. Clarke.

314

Robinson.

315

Matt. xiii. 2.

316

D'Anville.

317

Id.

318

Buckingham.

319

2 Kings xxiii. 10, 12. 2 Chron. xxvii. 3.

320

2 Kings xxiii. 10.

321

Brewster.

322

Robinson.

323

Id.

324

Carne.

325

John xx.

326

Ib. v. 4.

327

Ib. v. 5, 11.

328

Clarke.

329

Robinson.

330

La Martine.

331

Carne.

332

Id.

333

Robinson.

334

Id.

335

Josephus; Tacitus; Prideaux; Rollin; Stackhouse; Pococke; D'Anville; Gibbon; Rees; Brewster; Clarke; Eustace; Chateaubriand; Buckingham; Robinson; La Martine; Carne.

336

Rollin.

337

Polybius; Plutarch; Rollin; Titler; Barthelemy; Chateaubriand; Dodwell.

338

Shaw; Chandler; Kinneir; Malte-Brun; Buckingham; Porter.

339

Rollin.

340

Rollin.

341

Turner.

342

Those of Magnesia amounted to fifty talents every year, a sum equivalent to 11,250l. sterling.

343

Such was the custom of the ancient kings of the East. Instead of settling pensions on persons they rewarded, they gave them cities, and sometimes even provinces, which, under the name of bread, wine, &c., were to furnish them abundantly with all things necessary for supporting, in a magnificent manner, their family and equipage. – Rollin.

344

Civil Architecture, 617.

345

Pococke; Chandler; Encycl. Metrop.

346

Rollin.

347

Rollin.

348

Dodwell.

349

Rollin; Dodwell; Williams.

350

This was the same plan as Hannibal followed afterwards at the battle of Cannæ.

351

Rollin; Wheler; Barthelemy; Clarke; Dodwell.

352

Barthelemy; Rollin; Rees; Dodwell.

353

Thucydides; Dodwell.

354

This story is told at length in Statius's Thebaid.

355

Dodwell.

356

Thucydides; Pausanias; Plutarch; Rollin; Wheler; Chandler; Barthelemy; Dodwell.

357

Savary.

358

Rollin.

359

Rollin.

360

Alexandria may be supposed to have been partly built with its ruins.

361

Malte-Brun.

362

Rollin.

363

The London and Birmingham Railway is unquestionably the greatest public work ever executed, either in ancient or modern times. If we estimate its importance by the labour alone which has been expended on it, perhaps the Great Chinese Wall might compete with it; but when we consider the immense outlay of capital which it has required, – the great and varied talents which have been in a constant state of requisition during the whole of its progress, – together with the unprecedented engineering difficulties, which we are happy to say are now overcome, – the gigantic work of the Chinese sinks totally into the shade.

It may be amusing to some readers, who are unacquainted with the magnitude of such an undertaking as the London and Birmingham Railway, if we give one or two illustrations of the above assertion. The great pyramid of Egypt, that stupendous monument which seems likely to exist to the end of all time, will afford a comparison.

After making the necessary allowances for the foundations, galleries, &c., and reducing the whole to one uniform denomination, it will be found that the labour expended on the great pyramid was equivalent to lifting fifteen thousand seven hundred and thirty-three million cubic feet of stone one foot high. This labour was performed, according to Diodoras Siculus by three hundred thousand, to Herodotus by one hundred thousand men, and it required for its execution twenty years.