полная версия

полная версияRuins of Ancient Cities (Vol. 1 of 2)

Freinshemius, in his supplement to Livy, relates, after Leo the African15, that the tomb of Alexander the Great was still to be seen in his time, and that it was reverenced by the Mohammedans, as the monument, not only of an illustrious king, but of a great prophet. 16 The ancient city, together with its suburbs, was about seven leagues in length; and Diodorus informs us that the number of its inhabitants amounted to above 300,000, consisting only of the citizens and freemen; but that, reckoning the slaves and foreigners, they were allowed, at a moderate computation, to be upwards of a million. These vast numbers of people were enticed to settle here by the convenient situation of the place for commerce; since, besides the advantage of a communication to the eastern countries by the canal cut out of the Nile into the Red Sea, it had two very spacious and commodious ports, capable of containing the shipping of all the then trading nations in the world.

The harbour, called Portus Eunostus, lay in the centre of the city; thus rendering the ships secure, not only by nature but by art. The figure of this harbour was a circle, the entrance being nearly closed up by two artificial moles, which left a passage for two ships only to pass abreast. At the western extremity of one of these moles stood the celebrated tower called Pharos. The ruins of it are buried in the sea, at the bottom of which, in a calm day, one may easily distinguish large columns and several vast pieces of marble, which give sufficient proofs of the magnificence of the building in which they were anciently employed.

This light-house was erected by Ptolemy Philadelphus. Its architect was Sostratus of Cnidos; its cost was 180,000l. sterling, and it was reckoned one of the seven wonders of the world17. It was a large square structure built of white marble, on the top of which a fire was constantly kept burning, in order to guide ships by night. Pharos was originally an island at the distance nearly of a mile from the continent, but was afterwards joined to it by a causeway like that of Tyre.

This Pharos was destroyed, and, in its stead, a square castle was built without taste or ornament, and incapable of sustaining the fire of a single vessel of the line: at present, in a space of two leagues, walled round, nothing is to be seen but marble columns lying in the dust, and sawed in pieces; for the Turks make mill-stones of them; together with the remains of pilasters, capitals, obelisks, and mountains of ruins heaped on each other.

Alexandria had one peculiar advantage over all others: – Dinocrates, considering the great scarcity of good water in this country, dug very spacious vaults, which, having communication with all parts of the city, furnished its inhabitants with one of the chief necessaries of life. These vaults were divided into capacious reservoirs, or cisterns, which were filled, at the time of the inundation of the Nile, by a canal cut out of the Canopic branch, entirely for that purpose. The water was, in that manner, preserved for the remainder of the year; and being refined by the long settlement, was not only the clearest, but the wholesomest of any in Egypt. This grand work is still remaining; whence the present city, though built out of the ruins of the ancient one, still enjoys the benefactions of Alexander, its founder.

A street18, two thousand feet wide, began at the Marine gate, and ended at the gate of Canopus, adorned with magnificent houses, temples, and public edifices. Through this extent of prospect the eye was never satiated with admiring the marble, the porphyry, and the obelisks which were destined hereafter to adorn Rome and Constantinople. This street was indeed the finest the world ever saw.

Besides all the private buildings constructed with porphyry and marble, there was an admirable temple to Serapis, and another to Neptune; also a theatre, an amphitheatre, gymnasium, and circus. The materials had all the perfection which the experience of one thousand years could afford; and the wealth and exertions, not only of Egypt but of Asia. The place was extensive and magnificent; and a succession of wise and good princes rendered it, by means of Egyptian materials and Grecian taste, one of the richest and most perfect cities the world has ever beheld.

The palace occupied one quarter of the city; but within its precincts were a museum, extensive groves, and a temple containing the sepulchre of Alexander.

This city was also famous for a temple erected to the God Serapis, in which was a statue which the natives of Sinope (in Pontus) had bartered, in a season of famine, for a supply of corn. The temple was called the Serapion; and Ammianus Marcellinus assures us19, that it surpassed all the temples then in the world for beauty and magnificence, with the sole exception of the Capitol at Rome.

Ptolemy Soter made this city the metropolitan seat of arts and sciences. He founded the museum, the most ancient and most sumptuous temple ever erected by any monarch, in honour of learning; he filled it with men of abilities, and made it an asylum for philosophers of all descriptions, whose doctrines were misunderstood, and whose persons were persecuted; in whose unfeigned tribute of grateful praise he has found a surer road to everlasting renown, than his haughty nameless predecessors, who pretended to immortality, and braved both heaven and corroding time by the solid structure of their pyramids.

He founded also a library, which was considerably augmented by Ptolemy Philadelphus, and by the magnificence of his successors, was at length increased to 700,000 volumes.

In Cæsar's time, part of this library, – that portion which was situated in the quarter of the city called the Bruchion, – was consumed by fire; a conflagration which caused the loss of not fewer than 400,000 volumes.

This library, a short time after, received the increase of 200,000 volumes from Pergamus; Antony having given that library to Cleopatra. It was afterwards ransacked several times; but it was still a numerous and very celebrated library at the time in which it was destroyed by the Saracens, viz. A. D. 642; a history of which we shall soon have to relate.

The manner in which this library was originally collected, may be judged of, in no small degree, by the following relation: – All the Greek and other books that were brought into Egypt were seized and sent to the Museum, where they were transcribed by persons employed for that purpose; the copies were then delivered to the proprietors, and the originals were deposited in the library. Ptolemy Evergetes, for instance, borrowed the works of Sophocles, Euripides, and Æschylus, of the Athenians, and only returned them the copies, which he had caused to be transcribed in as beautiful a manner as possible; and he likewise presented them with fifteen talents, equal to fifteen thousand crowns, for the originals, which he kept.

On the death of Cleopatra, Egypt was reduced into a province of the Roman empire, and governed by a prefect sent from Rome. Alexander founded the city in 3629; and the reign of the Ptolemies, who succeeded him, lasted to the year of the world 3974.

The city, in the time of Augustus, must have been very beautiful; for when that personage entered it, he told the natives, who had acted against him, that he pardoned them all; first, out of respect to the name of their founder; and, secondly, on account of the beauty of their city. This beauty and opulence, however, were not without their corresponding evils; for Quintilian informs us, that as Alexandria improved in commerce and in opulence, her inhabitants grew so effeminate and voluptuous, that the word Alexandrine became proverbial, to express softness, indelicacy, and immodest language.

Egypt having become a province of Rome, some of the emperors endeavoured to revive in it a love of letters, and enriched it by various improvements. The emperor Caligula was inclined to favour the Alexandrians, because they manifested a readiness to confer divine honours upon him. He even conceived the horrid design of massacring the chief senators and knights of Rome (A. D. 40), and then of abandoning the city, and of settling at Alexandria; the prosperity and wealth of which in the time of Aurelian was so great, that, after the defeat of Zenobia, a single merchant of this city undertook to raise and pay an army out of the profits of his trade!

The rapid rise of the power of the Moslems, and the religious discord which prevailed in Egypt, levelled a death-blow at the grandeur of this powerful city, whose prosperity had been unchecked from the time of its foundation; – upwards of nine hundred and seventy years. Amrou, the lieutenant of Omar, king of the Saracens, having entered Egypt, and taken Pelusium, Babylon, and Memphis, laid siege to Alexandria, and after fourteen months carried the city by assault, and all Egypt submitted to the yoke of the Caliphs. The standard of Mahomet was planted on the walls of Alexandria A. D. 640. Abulfaragius, in his history of the tenth dynasty, gives the following account of this catastrophe: – John Philoponus, a famous Peripatetic philosopher, being at Alexandria when the city was taken by the Saracens, was admitted to familiar intercourse with Amrou, the Arabian general, and presumed to solicit a gift, inestimable in his opinion but contemptible in that of the barbarians, and this was the royal library. Amrou was inclined to gratify his wish, but his rigid integrity scrupled to alienate the least object without the Caliph's consent. He accordingly wrote to Omar, whose well-known answer was dictated by the ignorance of a fanatic.

Amrou wrote thus to his master, "I have taken the great city of the West. It is impossible for me to enumerate the variety of its riches and beauty; I shall content myself with observing, that it contains 4000 palaces, 4000 baths, 400 theatres or places of amusement, 12,000 shops for the sale of vegetable food, and 40,000 tributary Jews." He then related what Philoponus had requested of him. "If these writings of the Greeks," answered the bigoted barbarian, his master, "agree with the Koran, or book of God, they are useless, and need not be preserved; if they disagree they are pernicious, and ought to be destroyed." This valuable repository, therefore, was devoted to the flames, and during six months the volumes of which it consisted supplied fuel to the four thousand baths, which gave health and cleanliness to the city. "No complaint," says a celebrated moralist (Johnson), "is more frequently repeated among the learned, than that of the waste made by time among the labours of antiquity. Of those who once filled the civilised world with their renown nothing is now left but their names, which are left only to raise desires that never can be satisfied, and sorrow which never can be comforted. Had all the writings of the ancients been faithfully delivered down from age to age, had the Alexandrian library been spared, and the Palatine repositories remained unimpaired, how much might we have known of which we are now doomed to be ignorant, how many laborious inquiries and dark conjectures, how many collations of broken hints and mutilated passages might have been spared! We should have known the successions of princes, the revolutions of empires, the actions of the great, and opinions of the wise, the laws and constitutions of every state, and the arts by which public grandeur and happiness are acquired and preserved. We should have traced the progress of life, seen colonies from distant regions take possession of European deserts, and troops of savages settled into communities by the desire of keeping what they had acquired; we should have traced the progress and utility, and travelled upward to the original of things by the light of history, till in remoter times it had glimmered in fable, and at last been left in darkness." – "For my own part," says Gibbon, "I am strongly tempted to deny both the fact and the consequences." Dr. Drake also is disposed to believe, that the privations we have suffered have been occasioned by ignorance, negligence, and intemperate zeal, operating uniformly for centuries, and not through the medium of either concerted or accidental conflagration20.

The dominion of the Turks, and the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope, in 1499, completed its ruin; and from that time it has remained in decay. Its large buildings fell into ruins, and under a government which discouraged even the appearance of wealth, no person would venture to repair them, and mean habitations were constructed in lieu of them, on the sea-coast. Since that dismal epoch Egypt has, century after century, sunk deeper and deeper into a state of perfect neglect and ruin. In recent times, however, it has been under the immediate despotic rule of Mehemet Ali, nominally a pasha of the sultan of Constantinople, and a man apparently able and willing to do much towards restoring civilisation to the place of his birth.

The remains, in the opinion of some, have been greatly magnified. One writer21, for instance, states, "The present state of Alexandria affords a scene of magnificence and desolation. In the space of two leagues, inclosed by walls, nothing is seen but the remains of pilasters, of capitals, and of obelisks, and whole mountains of shattered columns and monuments of ancient art, heaped upon one another, and accumulated to a height even greater than that of the houses." Another writer22 says, "Alexandria now exhibits every mark by which it could be recognised as one of the principal monuments of the magnificence of the conqueror of Asia, the emporium of the East, and the chosen theatre of the far-sought luxuries of the Roman triumvirs and the Egyptian queen."

According to Sonnini, columns subverted and scattered about; a few others still upright but isolated; mutilated statues, fragments of every species, overspread the ground which it once occupied. "It is impossible to advance a step, without kicking, if I may use the expression, against some of its wrecks. It is the hideous theatre of destruction the most horrible. The soul is saddened on contemplating those remains of grandeur and magnificence; and it is raised into indignation against the barbarians, who dared to apply a sacrilegious hand to monuments, which time, the most pitiless of destroyers, would have respected." "So little," says Dr. Clarke, "are we acquainted with these valuable remains, that not a single excursion for purposes of discovery has yet been begun; nor is there any thing published with regard to its modern history, excepting the observations that have resulted from the hasty survey, made of its forlorn and desolated havens by a few travellers whose transitory visits ended almost with the days of their arrival23."

"On arriving at Alexandria," says Mr. Wilkinson, "the traveller naturally enquires where are the remains of that splendid city, which was second only to Rome itself, and whose circuit of fifteen miles contained a population of three hundred thousand inhabitants and an equal number of slaves; and where the monuments of its former greatness? He has heard of Cleopatra's Needle and Pompey's Pillar, from the days of his childhood, and the fame of its library, the Pharos, the temple of Serapis and of those philosophers and mathematicians, whose venerable names contribute to the fame of Alexandria, even more than the extent of its commerce or the splendour of the monuments, that once adorned it, are fresh in his recollection; – and he is surprised, in traversing mounds which mark the site of this vast city, merely to find scattered fragments or a few isolated columns, and here and there the vestiges of buildings, or the doubtful direction of some of the main streets."

Though the ancient boundaries, however, cannot be determined, heaps of rubbish are on all sides visible; whence every shower of rain, not to mention the industry of the natives in digging, discovers pieces of precious marble, and sometimes ancient coins, and fragments of sculpture. Among the last may be particularly mentioned the statues of Marcus Aurelius and Septimius Severus.24

The present walls are of Saracenic structure. They are lofty; being in some places more than forty feet in height, and apparently no where so little as twenty. These furnish a sufficient security against the Bedouins, who live part of the year on the banks of the canal, and often plunder the cattle in the neighbourhood. The few flocks and herds, which are destined to supply the wants of the city, are pastured on the herbage, of which the vicinity of the canal favours the growth, and generally brought in at night when the two gates are shut. "Judge," says M. Miot, "by Volney's first pages, of the impression which must be made upon us, by these houses with grated windows; this solitude, this silence, these camels; these disgusting dogs covered with vermin; these hideous women holding between their teeth the corner of a veil of coarse blue cloth to conceal from us their features and their black bosoms. At the sight of Alexandria and its inhabitants, at beholding these vast plains devoid of all verdure, at breathing the burning air of the desert, melancholy began to find its way among us; and already some Frenchmen, turning towards their country their weary eyes, let the expression of regret escape them in sighs; a regret which more painful proofs were soon to render more poignant." And this recals to one's recollection the description of an Arabic poet, cited by Abulfeda several centuries ago.

"How pleasant are the banks of the canal of Alexandria; when the eye surveys them the heart is rejoiced! the gliding boatman, beholding its towers, beholds canopies ever verdant; the lovely Aquilon breathes cooling freshness, while he, sportful, ripples up the surface of its waters; the ample Date, whose flexible head reclines like a sleeping beauty, is crowned with pendent fruit."

The walls to which we have alluded present nothing curious, except some ruinous towers; and one of the chief remains of the ancient city is a colonnade, of which only a few columns remain; and what is called the amphitheatre, on a rising ground, whence there is a fine view of the city and port. There is, however, one structure beside particularly entitled to distinction; and that is generally styled Pompey's Pillar.

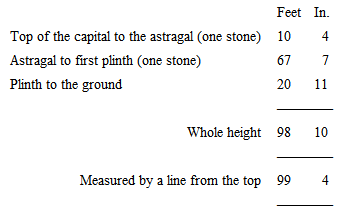

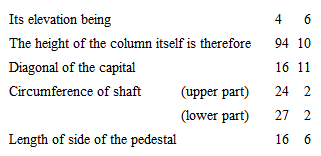

Pompey's Pillar, says the author of Egyptian Antiquities, "stands on a small eminence midway between the walls of Alexandria and the shores of the lake Mareotis, about three-quarters of a mile from either, quite detached from any other building. It is of a red granite; but the shaft, which is highly polished, appears to be of earlier date than the capital or pedestal, which have been made to correspond. It is of the Corinthian order; and while some have eulogised it as the finest specimen of that order, others have pronounced it to be in bad taste. The capital is of palm leaves, not indented. The column consists only of three pieces – the capital, the shaft, and the base – and is poised on a centre stone of breccia, with hieroglyphics on it, less than a fourth of the dimensions of the pedestal of the column, and with the smaller end downward; from which circumstance the Arabs believe it to have been placed there by God. The earth about the foundation has been examined, probably in the hopes of finding treasures; and pieces of white marble, (which is not found in Egypt) have been discovered connected to the breccia above mentioned. It is owing, probably, to this disturbance that the pillar has an inclination of about seven inches to the south-west. This column has sustained some trifling injury at the hands of late visiters, who have indulged a puerile pleasure in possessing and giving to their friends small fragments of the stone, and is defaced by being daubed with names of persons, which would otherwise have slumbered unknown to all save in their own narrow sphere of action; practices which cannot be too highly censured, and which an enlightened mind would scorn to be guilty of. It is remarkable, that while the polish on the shaft is still perfect to the northward, corrosion has begun to affect the southern face, owing probably to the winds passing over the vast tracts of sand in that direction. The centre part of the cap-stone has been hollowed out, forming a basin on the top; and pieces of iron still remaining in four holes prove that this pillar was once ornamented with a figure, or some other trophy. The operation of forming a rope-ladder to ascend the column has been performed several times of late years, and is very simple: a kite was flown, with a string to the tail, and, when directly over the pillar, it was dragged down, leaving the line by which it was flown across the capital. With this a rope, and afterwards a stout hawser, was drawn over; a man then ascended and placed two more parts of the hawser, all of which were pulled tight down to a twenty-four-pounder gun lying near the base (which it was said Sir Sidney Smith attempted to plant on the top); small spars were then lashed across, commencing from the bottom, and ascending each as it was secured, till the whole was complete, when it resembled the rigging of a ship's lower masts. The mounting this solitary column required some nerve, even in seamen; but it was still more appalling to see the Turks, with their ample trowsers, venture the ascent. The view from this height is commanding, and highly interesting in the associations excited by gazing on the ruins of the city of the Ptolemies, lying beneath. A theodolite was planted there, and a round of terrestrial angles taken; but the tremulous motion of the column affected the quicksilver in the artificial horizon so much as to preclude the possibility of obtaining an observation for the latitude. Various admeasurements have been given of the dimensions of Pompey's Pillar; the following, however, were taken by a gentleman who assisted in the operation above described: —

It will be remembered, however, that the pedestal of the column does not rest on the ground,

Shaw says, that in his time, in expectation of finding a large treasure buried underneath, a great part of the foundation, consisting of several fragments of different sorts of stone and marble, had been removed; so that the whole fabric rested upon a block of white marble scarcely two yards square, which, upon touching it with a key, sounded like a bell.

All travellers agree that its present appellation is a misnomer; yet it is known that a monument of some kind was erected at Alexandria to the memory of Pompey, which was supposed to have been found in this remarkable column. Mr. Montague thinks it was erected to the honour of Vespasian. Savary calls it the Pillar of Severus. Clarke supposes it to have been dedicated to Hadrian, according to his reading of a half-effaced inscription in Greek on the west side of the base; while others trace the name of Diocletian in the same inscription. No mention occurring of it either in Strabo or Diodorus Siculus, we may safely infer that it did not exist at that period; and Denon supposes it to have been erected about the time of the Greek Emperors, or of the Caliphs of Egypt, and dates its acquiring its present name in the fifteenth century. It is supposed to have been surmounted with an equestrian statue. The shaft is elegant and of a good style; but the capital and pedestal are of inferior workmanship, and have the appearance of being of a different period.

In respect to the inscription on this pillar, there are two different readings: – It must, however, be remembered, that many of the letters are utterly illegible.

TO DIOCLETIANUS AUGUSTUS,MOST ADORABLE EMPEROR,THE TUTELAR DEITY OF ALEXANDRIA,PONTIUS, A PREFECT OF EGYPT,CONSECRATES THISDr. Clarke's version is —

POSTHUMUS, PRÆFECT OF EGYPT,AND THE PEOPLE OF THE METROPOLIS,[honour] TO THE MOST REVERED EMPEROR,THE PROTECTING DIVINITY OF ALEXANDRIA,THE DIVINE HADRIAN AUGUSTUSNow, since it is known that Hadrian lived from A. D. 76 to 130, it seems clear that Pompey has no connexion with this pillar, and that it ought no longer to bear his name. Some writers, however, are disposed to believe that the inscription is not so old as the pillar, and this is very likely to be the case.

This celebrated pillar has of late years been several times ascended. The manner, as we have before stated, was this: – "By means of a kite, a strong cord was passed over the top of the column, and securely fastened on one side, while one man climbed up the other. When he had reached the top, he made the rope still more secure, and others ascended, carrying with them water of the Thames, of the Nile, and of one of the Grecian Islands: a due supply of spirits was also provided, and thus a bowl of punch was concocted; and the healths of distinguished persons were drunk. This ascent was made when the British fleet was in Egypt, since which time the ascents have been numerous; for, according to Mr. Webster, the crew of almost every man-of-war which has been stationed in the port of Alexandria have thought the national honour of British tars greatly concerned in ascending the height of fame, or, in other words, the famous height which Pompey's pillar affords. It is not unusual for a party to take breakfast, write letters, and transact other matters of business on this very summit; and it is on record that a lady once had courage to join one of these high parties."