полная версия

полная версияA Voyage Round the World, from 1806 to 1812

The game of draughts is now introduced, and the natives play it uncommonly well.

Flying kites is another favorite amusement. They make them of taper, of the usual shape, but uncommon size, many of them being fifteen or sixteen feet in length, and six or seven in breadth; they have often three or four hundred fathom of line, and are so difficult to hold, that they are obliged to tie them to trees.

The only employment I ever saw Tamena, the queen, engaged in, was making these kites.

A theatre was erected under the direction of James Beattie, the king’s block-maker, who had been at one time on the stage in England. The scenes representing a castle and a forest were constructed of different coloured pieces of taper, cut out and pasted together.

I was present on one occasion, at the performance of Oscar and Malvina. This piece was originally a pantomime, but here it had words written for it by Beattie. The part of Malvina was performed by the wife of Isaac Davis. As her knowledge of the English language was very limited, extending only to the words yes and no, her speeches were confined to these monosyllables. She, however, acted her part with great applause. The Fingalian heroes were represented by natives clothed in the Highland garb, also made out of taper, and armed with muskets.

The audience did not seem to understand the play well, but were greatly delighted with the after-piece, representing a naval engagement. The ships were armed with bamboo cannon, and each of them fired a broadside, by means of a train of thread dipped in saltpetre, which communicated with each gun, after which one of the vessels blew up. Unfortunately, the explosion set fire to the forest, and had nearly consumed the theatre.

The ceremonies that took place upon the death of a chief have been already described. The bodies of the dead are always disposed of secretly, and I never could learn where they were interred. My patroness, the queen, preserved the bones of her father, wrapt up in a piece of cloth. When she slept in her own house they were placed by her side; in her absence they were placed on a feather bed she had received from the captain of a ship, and which was only used for this purpose. When I asked her the reason of this singular custom, she replied, “it was because she loved her father so dearly.”

When the king goes to war, I understand that every man capable of bearing arms must follow his chief; for which purpose they are all trained from their youth to the use of arms. I saw nothing like a regular armed force, except a guard of about fifty men, who constantly did duty at the king’s residence. There were about twenty of them on guard daily, but the only sentry which they posted was at the powder magazine. At night he regularly called out every hour, “All’s well.”

They were armed with muskets and bayonets, but had no uniform; their cartridge-boxes, which were made by the king’s workmen, are of wood, about thirteen inches long, rounded to the shape of the body, and covered with hide.

I have seen those guards at their exercise; rapidity, and not precision, seemed to be their great object. The men stood at extended order, and fired as fast as they could, beating the butt upon the ground, and coming to the recover without using the ramrod; each man gave the word “fire,” before he drew the trigger.

The natives of these islands have been accused of being cannibals; but as far as I could judge, either from my own observation, or from the enquiries I made, I believe the accusation to be perfectly destitute of foundation. Isaac Davis, who had the best means of knowing, having resided there more than twenty years, and who had been present and borne a share in all their wars, declared to me most pointedly, that “it was all lies – that there never had been cannibals there since they were islands.”

From a perusal of the foregoing pages, it will be seen, that these islanders have acquired many of the useful arts, and are making rapid progress towards civilization. Much must be ascribed, no doubt, to their natural ingenuity and unwearied industry; but great part of the merit must also be ascribed to the unceasing exertions of Tamaahmaah, whose enlarged mind has enabled him to appreciate the advantages resulting from an intercourse with Europeans, and he has prosecuted that object with the utmost eagerness.

The unfortunate death of captain Cook, and the frequent murders committed by the natives on navigators, particularly in Wahoo, in which Lieutenant Hengist, and Mr. Gooch, astronomer of the Dædalus, Messrs. Brown and Gordon, masters of the ships Jackall and Prince Le Boo, lost their lives, gave such ideas of the savage nature of the inhabitants, that for many years few ships would venture to touch at these islands.29

But since Tamaahmaah has established his power, he has regulated his conduct by such strict rules of justice, that strangers find themselves as safe in his port as in those of any civilized nation.

Although always anxious to induce white people to remain, he gives no encouragement to desertion, nor does he ever attempt to detain those who wish to depart.

In 1809 the king seemed about fifty years of age; he is a stout, well-made man, rather darker in the complexion than the natives usually are, and wants two of his front teeth. The expression of his countenance is agreeable, and he is mild and affable in his manners, and possesses great warmth of feeling; for I have seen him shed tears upon the departure of those to whom he was attached, and has the art of attaching others to himself. Although a conquerer, he is extremely popular among his subjects; and not without reason, for since he attained the supreme power, they have enjoyed repose and prosperity. He has amassed a considerable treasure in dollars, and possesses a large stock of European articles of every description, particularly arms and ammunition; these he has acquired by trading with the ships that call at the islands. He understands perfectly well how to make a bargain; but is unjustly accused of wishing to over-reach in his dealings. I never knew of his taking any undue advantages; on the contrary, he is distinguished for upright and honourable conduct in all his transactions. – War, not commerce, seems to be his principal motive in forming so extensive a navy. Being at peace, his fleet was laid up in ordinary during the whole time of my stay. When he chooses to fit it out, he will find no difficulty in manning his vessels. Independently of the number of white people he has constantly about him, and who are almost all sailors, he will find, even among his own subjects, many good seamen. He encourages them to make voyages in the ships that are constantly touching at the islands, and many of them have been as far as China, the northwest coast of America, and even the United States. In a very short time they become useful hands, and continue so as long as they remain in warm climates; but they are not capable of standing the effects of cold.

During my stay the building of the navy was suspended, the king’s workmen being employed in erecting a house, in the European style, for his residence at Hanaroora. When I came away, the walls were as high as the top of the first story.

His family consisted of the two queens, who are sisters, and a young girl, the daughter of a chief, destined to the same rank. He had two sons alive, one about fifteen, and the other about ten years of age, and a daughter, born when I was upon the island.

The queen was delivered about midnight, and the event was instantly announced by a salute of sixteen guns, being a round of the battery in front of the house.

I was informed by Isaac Davis, that his eldest son had been put to death by his orders in consequence of criminal connexion with one of his wives. This took place before he fixed his residence at Wahoo.

His mode of life has already been described. He sometimes dressed himself in the European fashion, but more frequently laid aside his clothes, and gave them to an attendant, contenting himself with the maro. Another attendant carried a fan, made of feathers, for the purpose of brushing away the flies; whilst a third carried his spit-box, which was set round with human teeth, and had belonged, as I was told, to several of his predecessors.

It is said that he was at one time strongly addicted to the use of ardent spirits; but that, finding the evil consequences of the practice, he had resolution enough to abandon it. I never saw him pass the bounds of the strictest temperance.

His queen, Tamena, had not the same resolution; and although, when he was present, she durst not exceed, she generally availed herself of his absence in the morai to indulge her propensity for liquor, and seldom stopped short of intoxication. Two Aleutian women had been left on the island, and were favorite companions of hers. It was a common amusement to make them drunk; but, by the end of the entertainment, her majesty was generally in the same situation.

CHAPTER XI

Departure from Wahoo – Pass Otaheite – Double Cape-Horn – Arrival at Rio Janeiro – Transactions there, during a residence of nearly two years – Voyage home – and from thence to the United States.

The ship in which I left the Sandwich islands was called the Duke of Portland, commanded by captain Spence. She had procured a cargo of about one hundred and fifty tons of seal oil, and eleven thousand skins, at the island of Guadaloupe, on the coast of California, and had put into Wahoo for the purpose of procuring refreshments.

Every thing being ready, we sailed from Hanaroora on the 4th of March, and stood to the southward with pleasant weather.

In the beginning of April we descried the mountains of Otaheite, but did not touch at that island.

About a week before we doubled Cape Horn, we saw two large whales, and the boats were hoisted out in the hope of taking them, but it began to blow so hard that the attempt proved unsuccessful.

Early in May we passed Cape Horn; the captain stood as far south as the latitude of 60, and we never saw the land. Although the season was far advanced we did not experience the smallest difficulty in this part of the voyage.

A few days afterwards we made the Falkland islands; the land is of great height, and seems perfectly barren.

Upon the 25th we saw the coast of Brazil, and next day entered the harbour of Rio Janeiro.

Being apprehensive of a mortification in my legs, I applied for admission into the English hospital, which is situated in a small island that lies off the harbour. When captain Spence, who took me thither in his boat, mentioned that I had lost my feet in the service of the Americans, he was informed, that since that was the case, I must apply to them to take care of me.

I then went on board an American brig, called the Lion, the captain of which directed me to call on Mr. Baulch, the consul for that nation; by his interest I was admitted into the Portuguese hospital, de la miserecorde.

During the whole voyage I experienced the utmost attention and kindness from the captain and crew of the Duke of Portland; and when I quitted them they did not leave me unprovided for in a strange country; they raised a subscription, amounting to fifty dollars, which was paid into the hands of the Portuguese agent on my account.

I remained in the hospital ten weeks; the Portuguese surgeons, although they could not effect a cure, afforded me considerable relief, and I was dismissed as well as I ever expected to be.

I was now in a different situation from what I had been either at Kodiak or the Sandwich islands; I was in a civilized country, in which I must earn my subsistence by my own industry; but here, as well as there, I was under the protection of Divine Providence, and in all my misfortunes, I found friends who were disposed to assist me.

Mr. Baulch, the American consul, gave me a jar of the essence of spruce, which I brewed into beer; and having hired a negro with a canoe, I went about the ships, furnishing them with that, and other small articles of refreshment.

While engaged in this employment, I went on board the ship Otter, returning from the South Seas, under the command of Mr. Jobelin, whom I had seen in the same vessel at the Sandwich islands. He informed me that he had visited Wahoo a few months after my departure, and found all my friends in good health, except Isaac Davis, who had departed this life after a short illness.

In this manner I was not only enabled to support myself, but even to save a little money. I afterwards hired a house at the rent of four milreas a month, and set up a tavern and boarding house for sailors; this undertaking not proving successful, I gave it up for a butcher’s stall, in which I was chiefly employed in supplying the ships with fresh meat. This business proved a very good one, and I was sanguine in my hopes of being able to raise a small sum; but an unfortunate circumstance took place, which damped all my hopes, and reduced me again to a state of poverty.

In the night of the 24th July, my home was broken into, and I was robbed of every farthing I had, as well as of all my clothes.

As the purchase of carcasses required some capital, I was under the necessity of giving up my stall for the present. I again took myself to my old trade of keeping a bum-boat, till I had saved as much as enabled me to set up the stall again.

I was much assisted by the good offices of a gentleman from Edinburgh, of the name of Lawrie, who resided in my neighbourhood; he took great interest in my welfare, and was of essential service by recommending me to ships, as well as by occasionally advancing a little money to enable me to purchase a carcase.

The state of my health, however, prevented me from availing myself of the advantages of my situation; the sores in my legs, although relieved, had never healed, and gradually became so painful as to affect my health, and render me unable to attend to any business.

In consequence of this, I determined to return home, in hopes of having the cure effectually performed in my native country.

On the 5th of February, 1812, I quitted Rio Janeiro, after a stay of twenty-two months. I came home in the brig Hazard, captain Anderson, and arrived in the Clyde on the 21st of April, after an absence of nearly six years.

After residing nearly four years in my native country, and having still a desire to visit the Sandwich islands, I left Scotland, in the American ship Independence, commanded by captain John Thomas, on the 3d of September, 1816, for New-York. We had sixty-three passengers, and after a very tedious voyage of fifty-three days, we arrived in good health at our port of destination. I had been led to believe that I should find no difficulty in getting a passage to the Sandwich islands from New-York; but after a short residence there, I did not see any prospect of obtaining a conveyance thither. My funds growing low, I commenced soliciting subscribers for my work. In this I met with considerable success, and was enabled to publish an edition of one thousand copies. But on account of the ulcers in my legs never healing, and being apprehensive of mortification, I was deterred from proceeding any farther. I therefore applied to the governors of the New-York city hospital for admittance, with the intention of having my legs amputated higher up, so that I might not be troubled with them in future. I was accordingly admitted on the 4th of November, 1817; and on the 20th of the same month, one of my legs was taken off a little below the knee. The second operation was performed on the 17th of January following; and I was enabled to leave the hospital on the 3d of April, 1818.

I still wished to return to the Sandwich islands, and having so far recovered as to be able to walk about with considerable ease, and the favourable appearance of my wounds indicating a thorough cure, I therefore made application to several gentlemen in New-York, by whose means my intentions were represented to the Prudential Committee of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. By their advice I removed to the institution belonging to that body, at Cornwall, Litchfield county, Connecticut, in order that I might there study under the Rev. Herman Daggett, and that I might become acquainted with several young men, in that place from the Sandwich islands; to the end, that if ever it should please Divine Providence to permit me to visit those islands again, I might be able to render them and the cause of religion, all the assistance that lay in my power, and that my influence might be exerted on the side of virtue; and, above all things, that I might be instrumental in forwarding the introduction of missionaries into those dark and benighted islands of the sea.

APPENDIX.

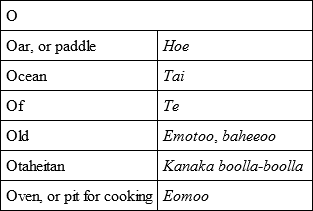

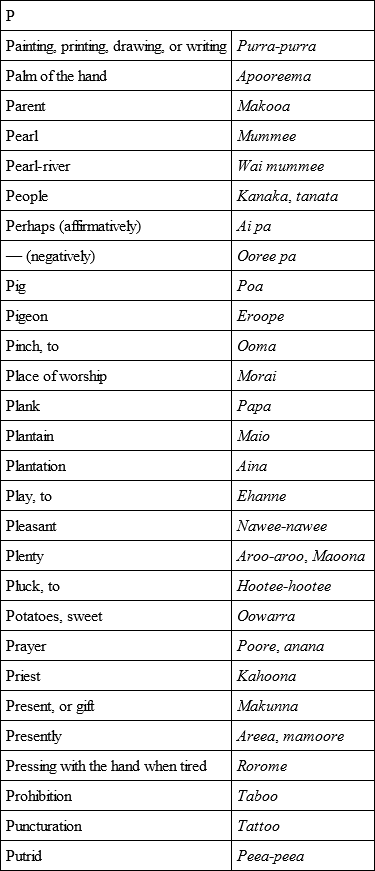

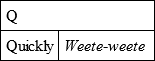

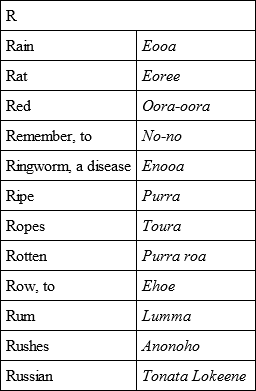

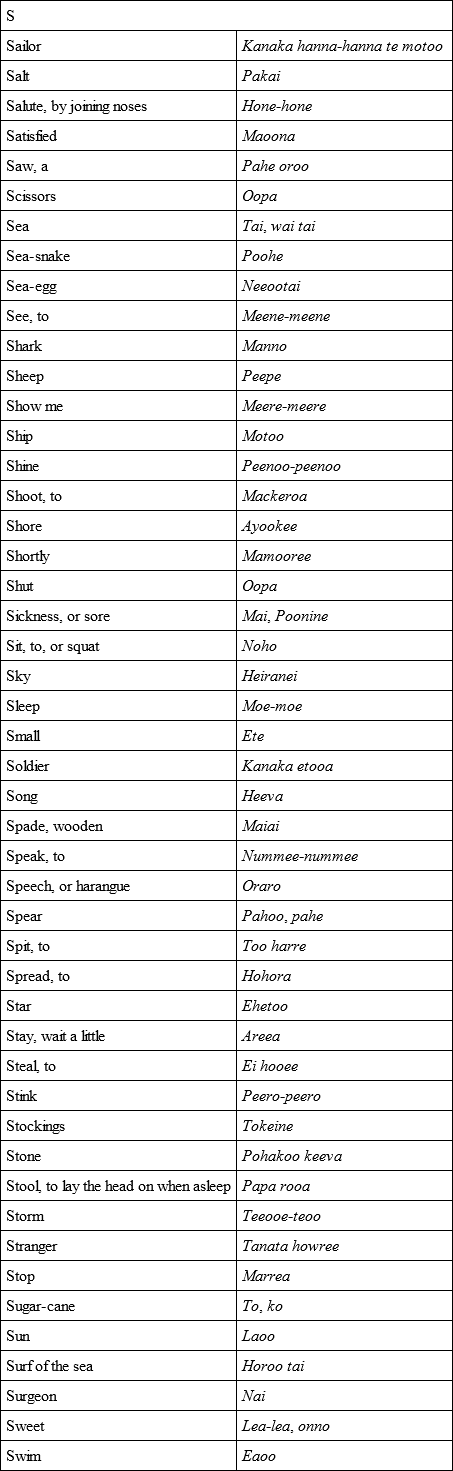

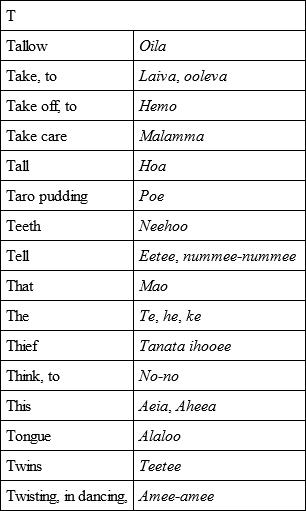

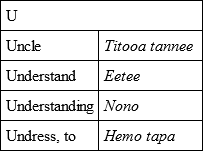

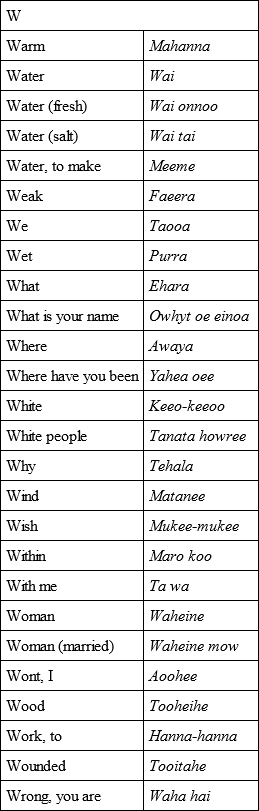

VOCABULARY OF THE LANGUAGE OF THE SANDWICH ISLANDS

APPENDIX No. I.

A VOCABULARY OF THE LANGUAGE OF THE SANDWICH ISLANDS

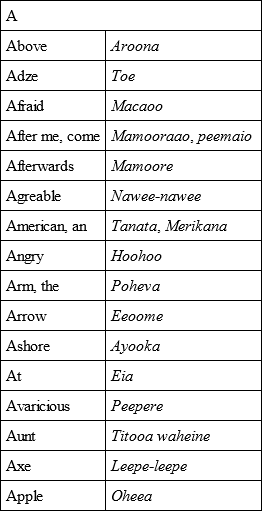

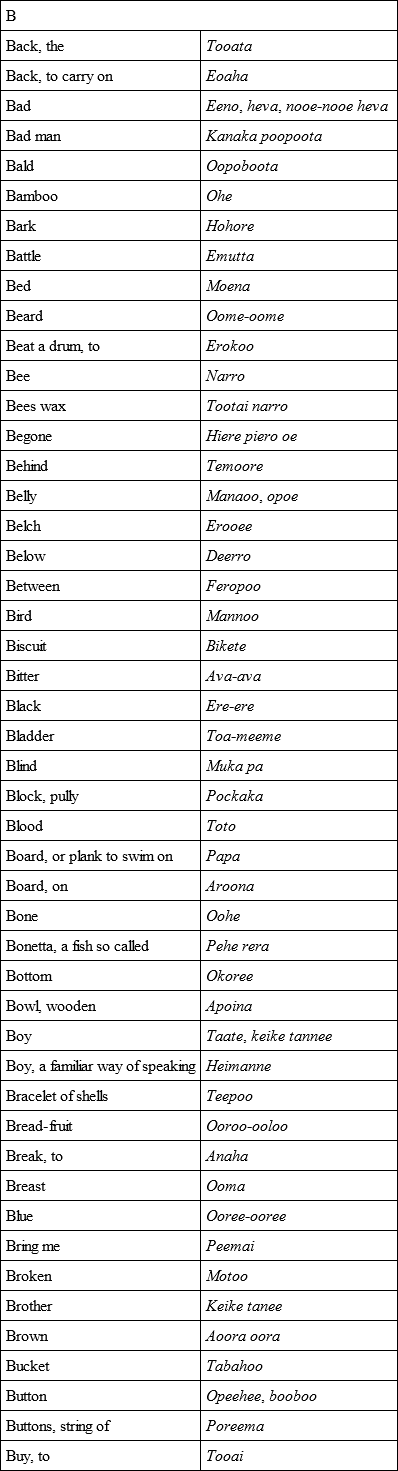

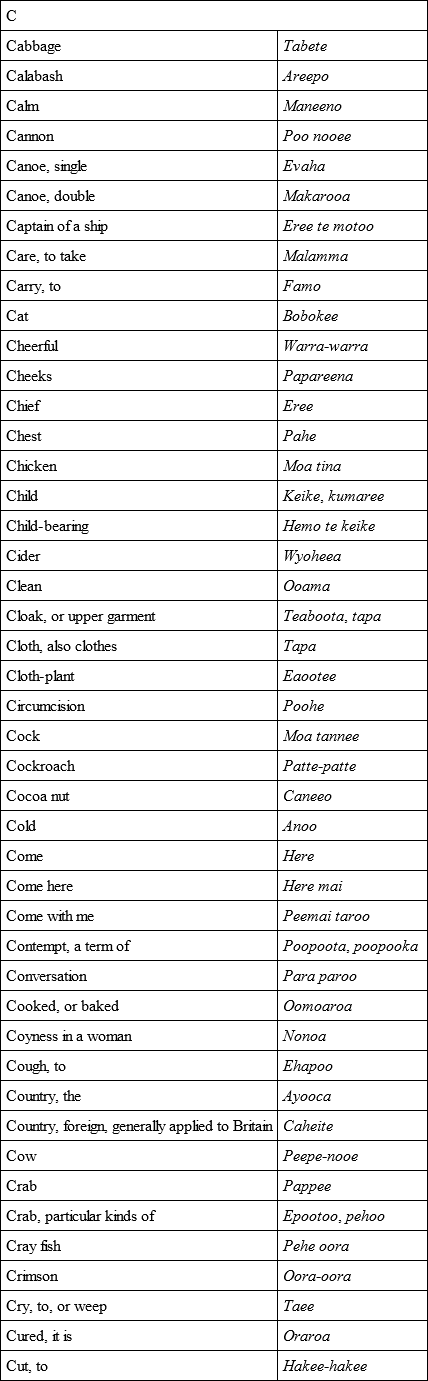

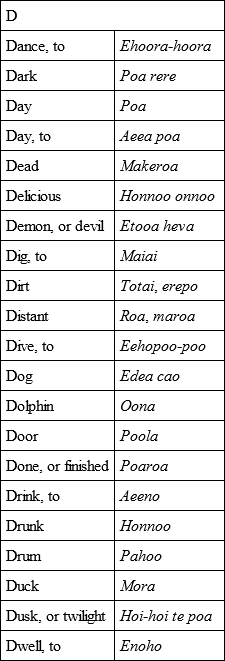

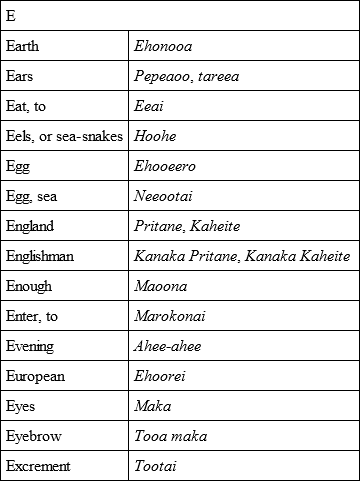

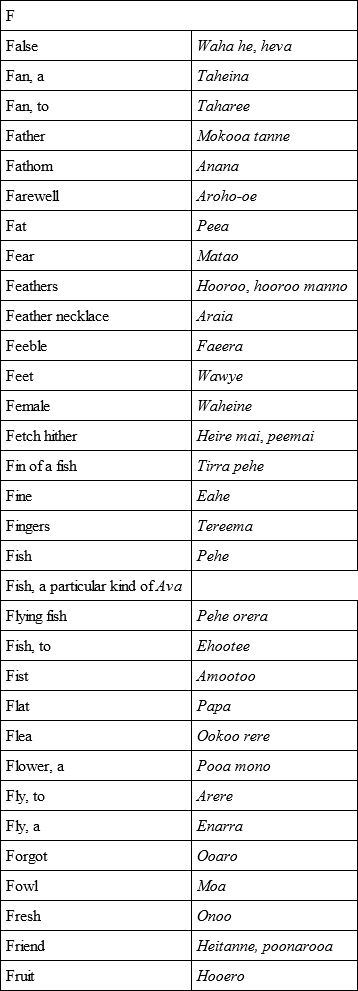

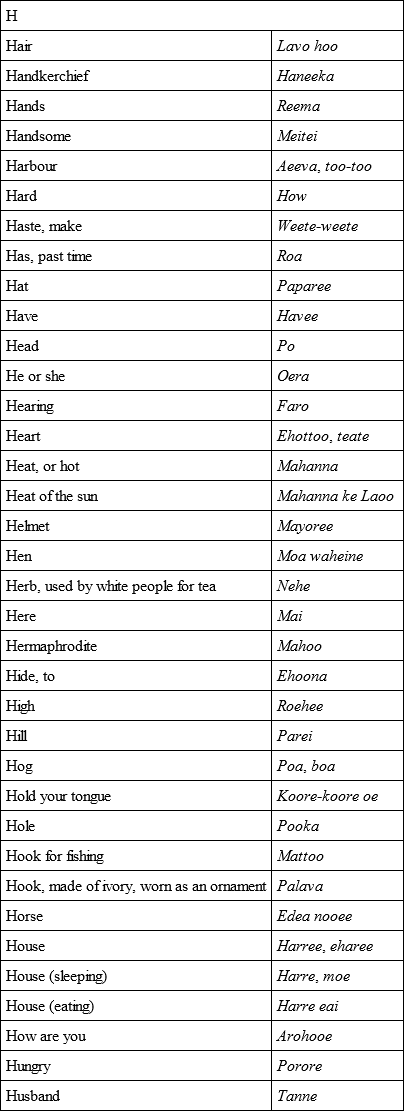

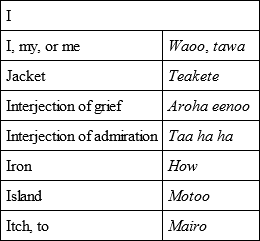

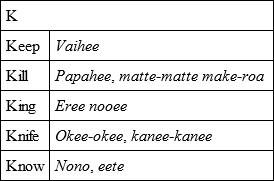

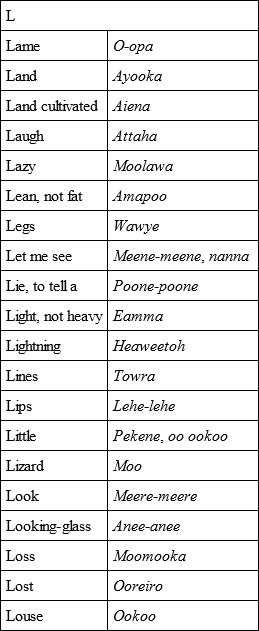

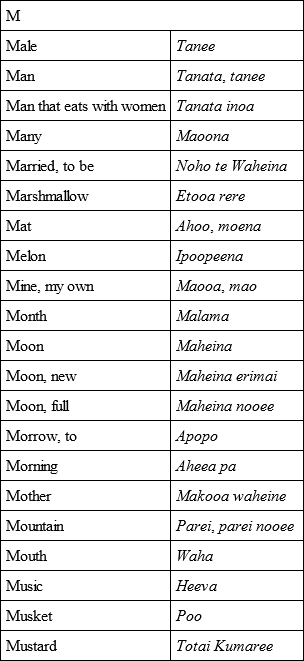

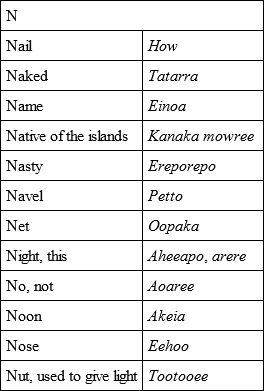

In pronouncing the words as spelt in the vocabulary, all letters must be sounded, with the exceptions after mentioned.

In sounding the vowels, A has always the sound of the initial and final letter in the word Arabia.

E, as in the word eloquence, or the final Y in plenty.

The double E, as in keep.

I, as in the word indolence.

O, as in the word form.

The double O, as in boot, good.

U, as in the word but.

The diphthongs Ai, as the vowel sounds in tye, fly, or the I in diameter.

Ei, as in the word height.

Oi, as in the word oil.

Ow, as in the word cow.

All other combinations of vowels are to be sounded separately; thus, oe, you, and roa, distant, are dissyllables.

In sounding the consonants, H is always aspirated; the letters K and T, L and R, B and P, are frequently substituted for each other.

Thus, kanaka, tanata, people; ooroo, ooloo, bread-fruit; boa, poa, a hog.

Where the words are separated by a comma, they are synonymous, and either may be used; but where there is no comma, both must be used.

Example. Taate, Keike tanne, a boy.

It frequently happens that the same word is repeated twice, in which case it is connected with a hyphen; thus leepe-leepe, an axe.

APPENDIX No. II.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE OF ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL

BY DR. NORDGOORST, IN THE SERVICE OF THE RUSSIAN AMERICAN COMPANY [Translated from the Russian.] STATEMENT OF THE CASE OF ARCHIBALD CAMPBELLThe bearer hereof, named Archibald Macbrait, has had the misfortune to have both of his feet frostbitten in so dreadful a manner, that nothing remained but to endeavour to save his life, as there were no hopes whatever of preserving his feet, although every attempt was made to that effect.

For the information of the humane and benevolent, I subjoin a short statement of my proceedings in his case, fearless of any compunctions of conscience; being sensible of the hard fate of this poor fellow creature, and how much he stands in need of assistance to support his existence.

This Englishman sailed from Kodiak in the winter time, in the ship’s cutter, for the island of Sannack. On their passage a storm came on, in which the boat was wrecked. The crew saved their lives on shore; but this man had both his feet frozen, and not having stripped off his clothes for twenty-seven days, he was not aware of the extent of his calamity, and did not apprehend the destruction of his feet.

The overseer of the district of Karlutzki brought him to Kodiak, at eight o’clock in the evening, to the hospital called the Chief District College of Counsellor and Chevalier Baranoff.

In the first place, I had his feet cleaned and dried; they were both in a state of mortification (gangrena sicca.) The mortified parts having separated from the sound to the distance of a finger’s breadth, where either amputation might take place or a cure be performed, as the patient himself hoped. I dressed the mortified, or frostbitten parts with oil of turpentine, and the unaffected parts with olive oil, and continued these applications for about five days, after which I used charcoal, gas, and other chimical applications; but as there appeared no chance of saving his feet, I began to consider that there was no resourse left but amputation. That the patient might not be alarmed, I talked over the matter with him as is usual in such cases, and endeavoured to persuade him to submit to the operation, as the only means of effecting a cure. But at first I was not successful, and could not get him to agree to it. I was therefore obliged to continue my former mode of treatment. At the end of three days, however, he gave his consent, and I fixed a time for the operations, which I performed satisfactorily. On the third day after the operation, the wound appeared to be in a good state, and I continued to dress it daily as it required.