полная версия

полная версияTime Telling through the Ages

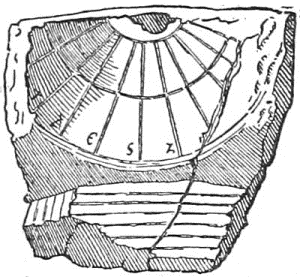

ANCIENT GREEK HEMICYCLE

This the ancients accomplished in a very simple and ingenious way. The sun moves in the sky as it were upon the inner surface of a hollow globe or sphere. So they made the dial a little hemisphere, place with its hollow side up toward the sky as a bowl stands on a table. The pointer was placed above and to the South of this, on the side toward the sun; and the Time was marked by the shadow of the tip end of the pointer which was a little ball or bead. The path of this shadow across the bowl reproduced exactly on a small scale the path of the sun across the great bowl of the heavens. And it was then an easy matter to mark off the bowl into equal divisions which the shadow would cross at equal intervals of the day. Of course, the track of the shadow changed with the season of the year. But it moved always as the sun moved, and just as regularly, giving a true measure of the solar day.

The principle of this was applied in several interesting variations. The defect of the Hemicycle, as this hollow type of dial was called, was that it could not be read accurately for short intervals. A shadow moving only a few inches in the whole day must move so slowly that one could hardly see it move at all. To mark the minutes, it must move faster, just as the minute hand of your watch moves faster than the hour hand, and the second hand faster still. One cannot read seconds from the hour hand, however accurately it moves, because it moves so slowly. So the idea was applied by making the shadow move across a street or courtyard, down one side and across and up the other side, as the sun opposite went up and across and down the sky. Sometimes the place was partly roofed over, and a single beam of light admitted through a small hole at the South end. The resulting spot of light would then move in the same way. The long sunbeam or shadow moved faster, and so could be read at shorter intervals. The Hemicycle is not certainly known to have been invented until long after this, about B. C. 350. But the principle of it is so simple and so entirely such as would occur to an intelligent man still ignorant of its mathematical explanation, that we may not unreasonably suppose it to have been discovered by experiments long before.

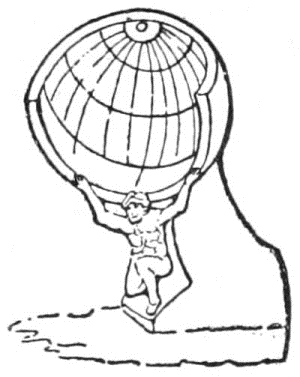

ANCIENT ROMAN HEMICYCLE

The final improvement of the sundial was the discovery that by slanting the gnomon so that it pointed exactly toward the North Pole of the sky, the direction of its shadow could be made to show the solar time correctly. Since the sky is infinitely far away, the line of the gnomon would then lie parallel to the axis of the heavens. And the sun, moving parallel to the celestial Equator, would always move straight across the gnomon. In other words, he would practically revolve around its sloping edge. Therefore the North and South motion of the sun would be as it were along the edge of the gnomon, and would not influence the direction of the shadow at all. His East and West motion alone would govern the swing of the shadow; and the dial would keep true time with the sun for every day in the year. There was no longer any necessity for hollowing out the dial itself into the concave form; it might just as well be the more convenient flat surface, and this might be either vertical or horizontal, so long as the gnomon pointed straight to the Celestial Pole. All that was needed was to mark out on the dial the true direction in which the shadow fell for each hour of the day.

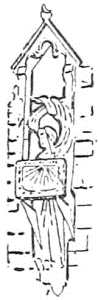

OLD ENGLISH DIAL

Just when or by whom the instrument was thus scientifically perfected is not known. The calculations necessary to the projection of the hour lines upon a flat surface could hardly have been performed before Greek times. The Greeks ascribed the invention of the sundial to Anaximander, in the sixth century B. C., but sundials of various types had been known in various parts of the world long before then. On the other hand, the Hemicycle remained the common form of the instrument all through the classic period and even afterwards. The Babylonians were quite capable of understanding the principle of the sloping gnomon. And once this was discovered, it would have been entirely practical to set up the new dial beside a Hemicycle or Clepsydra, and find the angles of the hour lines by experiment. These, once laid out correctly, would be determined once for all. Even at its best the sundial had certain very marked limitations. Scientifically constructed, it would keep accurate time according to the visible sun. But it could not be read accurately unless made inconveniently large. It was inaccurate when removed from its original latitude, or displaced from a true North and South position; so that in any portable form it became a very rough measure indeed. Moreover, it was of course entirely useless at night or in bad weather or in shadow. And finally, it was never absolutely exact under the most ideal conditions, because of what is known as the Equation of Time. The Earth does not, in fact, move around the sun at an absolutely regular rate of speed; it moves a trifle faster during certain parts of the year and slower at others. The sun therefore varies correspondingly his apparent speed along the Ecliptic, so that even from noon to noon the sun is not always precisely on time. He may be as much as fifteen minutes late or early, according to the season. And our modern days are measured according to the sun's average rate, so as to allow for this variation and keep every day exactly twenty-four hours long. This of course no sun-dial can possibly be made to do, since it must follow the actual sun.

The sun-dial has remained in use to the present day. It seems strange to think of a sun-dial being used as a standard for setting clocks and actually to regulate the running of trains. But these things were done in civilized Europe within the last half century. It was only when the railroad and the telegraph had made standard time at once necessary and easy to obtain that the sun-dial altogether lost its position of authority.

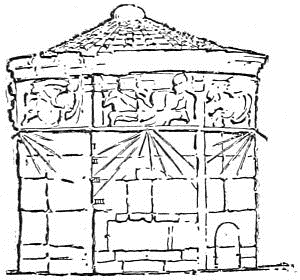

Sun-Dials, Descriptions – Classical sun-dials were of many forms. Vitruvius, the Roman engineer, mentions thirteen, some of them portable; and ascribes the invention of the Hemicycle to the Babylonian astronomer and priest, Berosus. There was a famous dial of this type at the base of Cleopatra's Needle in Egypt. It is now at the British Museum. And the Emperor Augustus, returning from his Egyptian wars, brought home to Rome an obelisk which he set up as the gnomon of a huge dial in the Campus Martius. At Athens there was the famous Tower of the Winds; octagonal in shape, with a weather vane above, and below around the tower, the hours and the winds, to each of which the Greeks gave a personality and a name. There is a curious bit of accidental poetry in the marking of the sun-dial in Greece. The Greek numerals, like the Roman, were simply the letters of their alphabet arranged in a certain order. The hot hours of the day from noon to four o'clock were those commonly devoted by the Greeks to rest and recreation. Reckoning the day from sunrise, this period ran from the sixth hour through the ninth. And the numeral letters for Six, Seven, Eight and Nine, which marked those hours upon the dial, spell out the Greek word ΖἩΟΙ, the imperative of the verb to live. The poet Lucian thus points the moral:

Six hours to labor, four to leisure give;In them – so say the dialled hours – LIVE.The shepherds of the Pyrenees still consult their pocket dials. And the Turk makes a sun-dial of his two hands by holding them up with the tips of the thumbs joined horizontally and the forefingers extended upward; so that the shadow of one forefinger falls toward the other and by its position roughly indicates the time. But even now, when it has nearly gone from practical use, the sun-dial, as an appropriate adornment of our public parks and our private gardens, is becoming increasingly fashionable in our own generation.

OLD FRENCH WALL DIAL

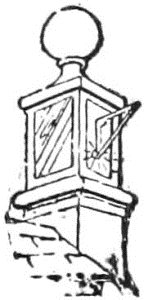

Sun-dials are common in almost all parts of the world, and not a few of them have in one way or another become famous. The largest is at Jaipur in India, and was erected about 1730. Its gnomon is ninety feet high and one hundred and forty-seven feet long. A flight of stone steps run up the slope of it, and at the top there is a sort of little watch-tower. And the shadow, which falls upon a great stone quadrant instead of upon a flat surface, moves at the rate of two and a half inches a minute. Another great dial is the so-called Calendar Stone of Mexico, which was made by the Aztec priests more than a hundred years before the Spaniards came. It weighs nearly fifty tons, and is not only a sun-dial but a representation of the zodiac and a diagram of the astronomical changes of the year: thus showing that the ancient Mexicans in their own way paralleled the astrology of the Babylonians on the other side of the world. Probably the most expensive and elaborate sun-dial ever built was the one set up in 1669 by King Charles II of England in front of the banqueting house at White Hall in London. It was in the form of a tall pyramid on which were two hundred and seventy-one different dials, giving not only the hour of the day but various astronomical and geographical indications as well. The place called Seven Dials in London takes its name from a tall pillar with sun-dials around its top which used to stand at the junction of seven streets radiating starwise from that spot as a center. The pillar was overthrown in 1773 by a party of vandals digging for buried treasure which they believed to have been hidden beneath its base. Extensive list, descriptions and illustrations, See Book of Sun-dials, Mrs. Alfred Gatty; Sun-dials and Roses, Mrs. Alice Morse Earle.

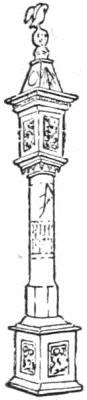

OLD ENGLISH PILLAR DIAL

Sun-Dials, Greek – 1. Diogenes asserts that the first Greek dial or gnomon was erected by Anaximander of Miletus. It was probably a vertical rod on a horizontal plane. This was two centuries after the Dial of Ahaz. 2. On the "Tower of the Winds" in Athens – a dial on each face.

Sun-Dial, Hollow – A form of sun-dial invented by the Chaldean Berosus. A hollow hemisphere with a bead at its center, whose shadow indicated the hour of the day.

Sun-Dial, Mottoes – On nearly all sun-dials both ancient and modern there there is inscribed a motto – usually of the moral significance of the passage of time.

Very ancient also, as well as equally common in modern times is the custom of placing upon the sun-dial some appropriate motto expressive of the mystery of Time. There are hundreds of such mottoes, ranging in sentiment from the old Roman one: Horas non numero nisi Serenas. "I number no hours but the fair ones," to the couplet of a modern poet:

"Time flies, you say? Ah no,Alas! Time stays; we go."And these two thoughts, expressed in many forms, represent fairly the tenor of most of them. There is a story of a lazy apprentice asking a motto for his dial, to whom his master sharply replied: "Begone about your business!" and the fellow, appropriately enough, took that for the motto required. It is at least a familiar sentiment, especially in Puritan times; and equally so during the Middle Ages is that more mystic suggestion, Umbra Dei– "the Shadow of God."

Sun-Dial, Portable – Made in different shapes and upon different plans small enough to carry about. The most common form was the ring dial, consisting of a metal ring with a hole in it through which the light fell upon an inside ring adjustable to the day and month. It required careful orienting to be dependable as a time-indicator.

Sun-Dials, Roman – The first dial in Rome was set up B. C. 293 near the temple of Quirinus by Papirius Cursor. It served ninety-nine years; then one more accurate was set up beside it. Before that, no time was noted except the rising and setting of the sun. Emperor Augustus erected a dial at Campus Martius. A dial captured in Sicily during the first Punic war was set up in the Forum about 263 B. C. and used for years before they learned that it was inaccurate in that latitude, being designed for the latitude of Sicily.

Sunk-Seconds – A dial in which the seconds circle is sunk below the rest of the dial. It allows the hour hand to be placed closer to the face thus making a thinner model possible.

Supplementary Arc – See: "Lifting Arc."

Sweep-Seconds – See: Center-Seconds.

Table Roller – The roller of a lever escapement which carries the impulse pin.

Tell-Tale Clock – A clock by which a record is left of periodical visits of some one as a night-watchman.

Template or Timplet – One of the four facets that surround a cut gem.

Tenon – A projection at the end of a piece cut to fit into a corresponding mortise.

Terry, Eli – The first man to make clocks by machinery in America. When it was learned that he planned to make two hundred clocks he was much laughed at. He was born at East Windsor, Conn., in 1772. His first clocks were made by hand, the movements being of wood. He was the leading maker of wooden clocks in America. He invented the shelf clock which contained distinctly new inventions and he introduced the pillar scroll-top case. He was a mechanical genius and contributed a great deal to developing clock-making in America into a great industry. He died in 1852.

Third Wheel – The wheel in the train between the center wheel and the fourth wheel.

Thales – A celebrated Ionian astronomer, one of the Seven Sages of Greece. He was born about 640 B. C., and is credited by Herodotus with having predicted an eclipse of the sun occurring about 609 B. C. He was the author of several solutions of geometrical problems. He died about 550 B. C.

Thomas, Seth – Born at Wolcott, Conn., 1785. A very successful clockmaker who contributed probably more than any other man toward popularizing the modern cheap clock. The Seth Thomas Clock Co., of today, he started in 1813 with twenty operatives. By 1853 it had nine hundred. He died in 1859.

Three-Quarter Plate – A three-quarter plate watch is one in which there is a piece cut out from the top plate large enough to permit the balance to rotate on a level with that plate. It is the most common form at present in use in both cheap and high grade watches, and found in both "pillar" and "bridge" models.

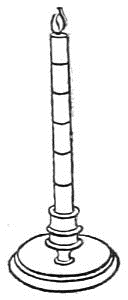

Time-Candles – Candles in alternate black and white sections were used to mark the passage of time in Europe and Asia for a long time. In England and France they were used to limit the bidding at an auction. The phrase "by inch of candle" meant that the one bidding when the flame expired was the successful bidder. King Alfred is said to have used time-candles and to have inclosed them in thin horn plates to protect them from drafts, thus originating the lantern.

Timekeeper – Any device primarily concerned with measuring and indicating the sub-divisions of the day.

Tompion, Thomas – "The father of English Watchmaking." Born 1638. He was the leading watchmaker at the court of Charles II. He found the construction of the time-keeping part of watches in a very indifferent condition and he left English clocks and watches the finest in the world, although many great improvements were made after his time. He associated closely with such scientists as Hooke, and Barlow, and made practical application of their theories – two notable instances being the cylinder escapement and the balance-spring. Tompion was the first to number his watches consecutively for the purpose of identification though he did not so mark his early ones. There is a famous clock in the pumproom at Bath, England, of Tompion's construction. Little is known of his domestic life but he appears to have been unmarried. He died in 1713 and is buried in Westminster Abbey. Tompion was master of the Worshipful Clockmakers' Company in 1704.

Top Plate – The plate in a watch farthest from the dial. In full plate watches it is circular; in three-quarter plate or half-plate watches a part is cut away.

Tower of the Winds – An octagonal tower north of the Acropolis of Athens spoken of as horological by Vario and Vitruvius. Believed to have had a sundial on each of its eight faces and to have contained a clepsydra fed by a spring.

Train – The toothed wheels of a watch or clock which connect the barrel or fusee with the escapement. In a going-barrel watch the teeth about the barrel drive the center pinion which drives the center wheel and then in turn the third wheel pinion, third wheel, fourth wheel pinion and fourth wheel, escape pinion and escape wheel.

Tripping – The running past the pallet's locking face, of an escape wheel tooth.

Vacheron and Constantin – In 1840 established the first complete watch factory in Switzerland. Not until later, however, was motor power used instead of foot-power; and later still manufacture by machinery. The work in this factory is carried on under a combination of all accepted methods.

Vailly, Dom – A Benedictine monk of about 1690 who made a water clock which Beckmann says was the first to be constructed on a really scientific principle. See Clocks, Interesting Old – Vailly's.

Van der Woerd, Charles – A prominent man in connection with watch manufacturing in this country. In 1864 he invented an automatic pinion cutter; in 1874 an automatic screw machine. From 1876-1883 he was superintendent of the Waltham factory.

Verge – The pallet axis of the verge escapement. See diagram of Verge Escapement. It carries the balance at its top.

Verge Watch – A watch with a verge escapement.

Vick, Henry de. See De Vick.

Volute – A flat spiral.

Volute-Spring – A flat metallic spring coiled in a spiral conical form and compressible in the direction of its axis.

Wallingford, Richard – An English mechanic and astronomer of the fourteenth century. He made a clock which is supposed to have been the first that was regulated by a fly-wheel. Several authorities, however, claim that Wallingford's "clock" was actually a planetarium.

Waltham – A town in Massachusetts – the site of the first successful watch factory in America. At present a great watch making center.

Watch – In modern parlance, a small timepiece to carry about on the person. Formerly a timepiece which showed time in distinction to clock which struck time. Derham (1734) uses the term to indicate all timepieces driven by springs. The term may have been derived from the Swedish vacht, German wachen, or Saxon woecca. The spaces of time between the fillings of a clepsydra were also called "watches."

Watch Collections – For list of principal collections, past and present, see Jewelers' Circular files August to December 1915. List compiled by Major Paul M. Chamberlain of Chicago. For list of principal present collections, see Appendix to this volume derived from the Chamberlain Compilation.

Watchmakers' Schools – American. In America these schools usually teach watch-repairing and not the making of watches. Some of them offer courses in making watches but few pupils avail themselves of these courses. List of: De Selins Watch School, Attica, Ind.; Detroit Technical Institute – Detroit, Mich.; Kansas City Watchmaking and Engraving School, Kansas City, Mo.; Needles Institute of Watchmaking, Kansas City, Mo.; Bowman Technical School, Lancaster, Pa.; Ries and Armstrong, Macon, Ga.; Drexler School for Watchmaking, Milwaukee, Wis.; Newark Watchmaking School, Newark, N. J.; Philadelphia College of Horology, Philadelphia, Pa.; St. Louis Watchmaking School, St. Louis, Mo.; Schwartzman's Trade Schools, San Francisco, Cal.; Stone School of Watchmaking, St. Paul, Minn.; Waltham Horological School, Waltham, Mass.; Bradley Polytechnic Institute, Peoria, Ill.

Watchmakers' Schools, Switzerland – Usually under government management. Teach very thoroughly and completely the art of making a watch from the beginning.

Watch-Papers – During the 18th century it was a fad in England and America to carry small round papers, which exactly fitted the case of a watch. On these were portraits and verses, the latter of doubtful merit and usually of sinister or gloomy significance.

Waterbury – A town in Connecticut long a center of clock and watch making in America. Home of the original Waterbury watch. Location of principal factory of Robt. H. Ingersoll & Brothers., manufacturers of the Ingersoll watches.

Water-Clock – Any device, as a clepsydra, for measuring time by the fall or flow of water. More commonly applied to the type in which wheels are turned by water or in such as those in which water sets machinery of some form in motion as Vailly's water-clock. See Clock, Vailly's.

Wick Timekeeper – A wick or rope made of some fiber resembling flax or hemp with knots tied at regular intervals and so treated that upon ignition it would smolder instead of breaking into flame. Early in use in Japan and China. Time was estimated by the burning between the knots.

Wieck, Henry De – See De Vick.

Willard, Aaron – Born 1757. Probably learned his trade from his older brothers Simon and Benjamin. He made tall, and shelf clocks, later banjo clocks – so-called from their shape – gallery clocks, and regulators. A better business man than his brothers and successful from the start. His clocks did not lack decorative merit but were inferior to Simon Willard's. He made a greater number than his brother because more successful in a business way.

Willard, Benjamin – Older brother of Simon and Aaron Willard. Among the first of American clockmakers. Born 1743. Made, probably, only tall clocks with handsome cases and some with musical attachments. Not so good as the clocks of Aaron and Simon Willard but older and rarer now.

Willard, Simon – Born at Grafton, Mass., 1753. One of the earliest Massachusetts clock makers who disputed the claim of the Connecticut makers for the credit of revolutionizing the clock industry in America. So far as cases go they excelled Terry, Thomas, and others. But to the Connecticut makers belongs the credit for having developed clock making into a great industry. Willard at first made eight-day tall clocks and shelf clocks, later wall clocks which he called "time pieces." In 1802 he practically abandoned the making of tall clocks, and confined himself to his "time pieces" and special orders for tower and gallery clocks. For a detailed list of his productions see his Biography by John Ware Willard. He was an intimate friend of Jefferson, Madison and other leading men of the time. Died 1848.

Worshipful Clockmakers' Company of London, The – Incorporated August 22, 1631, under special charter by King Charles I of England. Was given the sole privilege of regulating the watch and clock trade in and for ten miles around London.

Webster, Ambrose – Mechanical superintendent, and later assistant superintendent, of the Waltham factory until his resignation in 1876. He systematized the work in the shop, standardized the measuring system, and forced automatic machinery to the front. He designed the first watch factory lathe with hard spindles and bearings of the two taper variety. He made the first interchangeable standard for parts of lathes. He invented many machines now in use, among them being the automatic pinion cutter.

Weight-Clock – A clock whose driving power is a weight suspended by a cord wound on a drum or cylinder.

Weights – The first clocks were made with a weight on a cord which was wound around a cylinder connected with the train. The weight descending caused the cylinder to revolve, setting the train in motion. Too rapid unwinding was prevented by the escapement. The weight as a driving power is still used, especially in large clocks.