полная версия

полная версияBuffon's Natural History, Volume I (of 10)

This ice, which is looked upon as a barrier that opposes the navigation near the poles, and the discovery of the southern continent, proves only that there are large rivers adjacent to the places where it is met with; and indicates also there are vast continents from whence these rivers flow; nor ought we to be discouraged at the sight of these obstacles; for if we consider, we shall easily perceive, this ice must be confined to some particular places; that it is almost impossible that it should occupy the whole circle which encompasses, as we suppose, the southern continent, and therefore we should probably succeed if we were to direct our course towards some other point of this circle. The description which Dampier and some others have given of New Holland, leads us to suspect that this part of the globe is perhaps a part of the southern lands, and is a country less ancient than the rest of this unknown continent. New Holland is a low country, without water or mountains, but thinly inhabited, and the natives without industry; all this concurs to make us think that they are in this continent nearly what the savages of Amaconia or Paraguais are in America. We have found polished men, empires, and kings, at Peru and Mexico, which are the highest, and consequently the most ancient countries of America. Savages, on the contrary, are found in the lowest and most modern countries; therefore we may presume that we should also find men united by the bands of society in the upper countries, from whence these great rivers, which bring this prodigious ice to the sea, derive their sources.

The interior parts of Africa are unknown to us, almost as much as they were to the ancients: they had, like us, made the tour of that vast peninsula, but they have left us neither charts, nor descriptions of the coasts. Pliny informs us, that the tour of Africa was made in the time of Alexander the Great, that the wrecks of some Spanish vessels had been discovered in the Arabian sea, and that Hanno, a Carthaginian general, had made a voyage from Gades to the Arabian sea, and that he had written a relation of it. Besides that, he says Cornelius Nepos tells us that in his time one Eudoxus, persecuted by the king Lathurus, was obliged to fly from his country; that departing from the Arabian gulph, he arrived at Gades, and that before this time they traded from Spain to Ethiopia by sea16. Notwithstanding these testimonies of the ancients, we are persuaded that they never doubled the Cape of Good Hope, and the course which the Portuguese took the first to go to the East-Indies, was looked upon as a new discovery; it will not perhaps, therefore, be deemed amiss to give the belief of the 9th century on this subject.

"In our time an entire new discovery has been made, which was wholly unknown to those who lived before us. No one thought, or even suspected, that the sea, which extends from India to China, had a communication with the Syrian sea. We have found, according to what I have learnt, in the sea Roum, or Mediterranean, the wreck of an Arabian vessel, shattered to pieces by the tempest, some of which were carried by the wind and waves to the Cozar sea, and from thence to the Mediterranean, and was at length thrown on the coast of Syria. This proves that the sea surrounds China and Cila, the extremity of Turqueston and the country of the Cozars; that it afterwards flows by the strait till it has washed the coast of Syria. The proof is drawn from the construction of the vessel; for no other vessels but those of Siraf are built without nails, which, as was the wreck we speak of, are joined together in a particular manner, as if they were sewed. Those, of all the vessels of the Mediterranean and of the coast of Syria, are nailed and not joined in this manner17."

To this the translator of this ancient relation adds. —

"Abuziel remarks, as a new and very extraordinary thing, that a vessel was carried from the Indian sea, and cast on the coasts of Syria. To find a passage into the Mediterranean, he supposes there is a great extent above China, which has a communication with the Cozar sea, that is, with Muscovia. The sea which is below Cape Current, was entirely unknown to the Arabs, by reason of the extreme danger of the navigation, and from the continent being inhabited by such a barbarous people, that it was not easy to subject them, nor even to civilize them by commerce. From the Cape of Good Hope to Soffala, the Portuguese found no established settlement of Moors, like those in all the maritime towns as far as China, which was the farthest place known to geographers; but they could not tell whether the Chinese sea, by the extremity of Africa, had a communication with the sea of Barbary, and they contented themselves with describing it as far as the coast of Zing, or Caffraria. This is the reason why we cannot doubt but that the first discovery of the passage of this sea, by the Cape of Good Hope, was made by the Europeans, under the conduct of Vasco de Gama, or at least some years before he doubled the Cape, if it is true there are marine charts of an older date, where the Cape is called by the name of Frontiera du Africa. Antonio Galvin testifies, from the relation of Francisco de Sousa Tavares, that, in 1528, the Infant Don Ferdinand shewed him such a chart, which he found in the monastery of Acoboca, dated 120 years before, copied perhaps from that said to be in the treasury of St. Mark, at Venice, which also marks the point of Africa, according to the testimony of Ramusio, &c."

The ignorance of those ages, on the subject of the navigation around Africa, will appear perhaps less singular than the silence of the editor of this ancient relation on the subject of the passages of Herodotus, Pliny, &c. which we have quoted, and which proves the ancients had made the tour of Africa.

Be it as it may, the African coasts are now well known; but whatever attempts have been made to penetrate into the inner parts of the country, we have not been able to attain sufficient knowledge of it to give exact relations18. It might, nevertheless, be of great advantage, if we were, by Senegal, or some other river, to get farther up the country and establish settlements, as we should find, according to all appearances, a country as rich in precious mines as Peru or the Brazils. It is perfectly known that the African rivers abound with gold, and as this country is very mountainous, and situated under the equator, it is not to be doubted but it contains, as well as America, mines of heavy metals, and of the most compact and hard stones.

The vast extent of north and east Tartary has only been discovered in these latter times. If the Muscovite maps are just, we are at present acquainted with the coasts of all this part of Asia; and it appears that from the point of eastern Tartary to North America, it is not more than four or five hundred leagues: it has even been pretended that this tract was much shorter, for in the Amsterdam Gazette, of the 24th of January, 1747, it is said, under the article of Petersburgh, that Mr. Stalleravoit had discovered one of these American islands beyond Kamschatca, and demonstrated that we might go thither from Russia by a shorter tract. The Jesuits, and other missionaries, have also pretended to have discovered savages in Tartary, whom they had catechised in America, which should in fact suppose that passage to be still shorter19. This author even pretends, that the two continents of the old and new world join by the north, and says, that the last navigations of the Japanese afford room to judge, that the tract of which we have spoken is only a bay, above which we may pass by land from Asia to America. But this requires confirmation, for hitherto it has been thought that the continent of the north pole is separated from the other continents, as well as that of the south pole.

Astronomy and Navigation are carried to so high a pitch of perfection, that it may reasonably be expected we shall soon have an exact knowledge of the whole surface of the globe. The ancients knew only a small part of it, because they had not the mariner's compass. Some people have pretended that the Arabs invented the compass, and used it a long time before we did, to trade on the Indian sea, as far as China; but this opinion has always appeared destitute of all probability; for there is no word in the Arab, Turkish, or Persian languages, which signifies the compass; they make use of the Italian word Bossola; they do not even at present know how to make a compass, nor give the magnetical quality to the needle, but purchase them from the Europeans. Father Maritini says, that the Chinese have been acquainted with the compass for upwards of 3000 years; but if that was the case, how comes it that they have made so little use of it? Why did they, in their voyages to Cochinchina, take a course much longer than was necessary? And why did they always confine themselves to the same voyages, the greatest of which were to Java and Sumatra? And why did not they discover, before the Europeans, an infinity of fertile islands, bordering on their own country, if they had possessed the art of navigating in the open seas? For a few years after the discovery of this wonderful property of the loadstone, the Portuguese doubled the Cape of Good Hope, traversed the African and Indian seas, and Christopher Columbus made his voyage to America.

By a little consideration, it was easy to divine there were immense spaces towards the west; for, by comparing the known part of the globe, as for example, the distance of Spain to China, and attending to the revolution of the Earth and Heavens, it was easy to see that there remained a much greater extent towards the west to be discovered, than what they were acquainted with towards the east. It, therefore, was not from the defect of astronomical knowledge that the ancients did not find the new world, but only for want of the compass. The passages of Plato and Aristotle, where they speak of countries far distant from the Pillars of Hercules, seem to indicate that some navigators had been driven by tempest as far as America, from whence they returned with much difficulty; and it may be conjectured, that if even the ancients had been persuaded of the existence of this continent, they would not have even thought it possible to strike out the road, having no guide nor any knowledge of the compass.

I own, that it is not impossible to traverse the high seas without a compass, and that very resolute people might have undertaken to seek after the new world by conducting themselves simply by the stars. The Astrolabe being known to the ancients, it might strike them they could leave France or Spain, and sail to the west, by keeping the polar star always to the right, and by frequent soundings might have kept nearly in the same latitude; without doubt the Carthaginians, of whom Aristotle makes mention, found the means of returning from these remote countries by keeping the polar star to the left; but it must be allowed that a like voyage would be looked upon as a rash enterprize, and that consequently we must not be astonished that the ancients had not even conceived the project.

Previous to Christopher Columbus's expedition, the Azores, the Canaries, and Madeira were discovered. It was remarked, that when the west winds lasted a long time, the sea brought pieces of foreign wood on the coast of these islands, canes of unknown species, and even dead bodies, which by many marks were discovered to be neither European nor African. Columbus himself remarked, that on the side of the west certain winds blew only a few days, and which he was persuaded were land winds; but although he had all these advantages over the ancients, and the knowledge of the compass, the difficulties still to conquer were so great, that there was only the success he met with which could justify the enterprise. Suppose, for a moment, that the continent of the new world had been 1000 or 1500 miles farther than it in fact is, a thing with Columbus could neither know nor foresee, he would not have arrived there, and perhaps this great country might still have remained unknown. This conjecture is so much the better founded, as Columbus, although the most able navigator of his time, was seized with fear and astonishment in his second voyage to the new world; for as in his first, he only found some islands, he directed his course more to the south to discover a continent, and was stopt by currents, the considerable extent and direction of which always opposed his course, and obliged him to direct his search to the west; he imagined that what had hindered him from advancing on the southern side was not currents, but that the sea flowed by raising itself towards the heavens, and that perhaps both one and the other touched on the southern side. True it is, that in great enterprises the least unfortunate circumstance may turn a man's brain, and abate his courage.

ARTICLE VII.

ON THE PRODUCTION OF THE STRATA, OR BEDS OF EARTH

We have shewn, in the first article, that by virtue of the mutual attraction between the parts of matter, and of the centrifugal force, which results from its diurnal rotation, the earth has necessarily taken the form of a spheroid, the diameters of which differ about a 230th part, and that it could only proceed from the changes on the surface, caused by the motion of the air and water, that this difference could become greater, as is pretended to be the case from the measures taken under the equator, and within the polar circle. This figure of the earth, which so well agrees with hydrostatical laws, and with our theory, supposes the globe to have been in a state of liquefaction when it assumed its form, and we have proved that the motions of projection and rotation were imprinted at the same time by a like impulsion. We shall the more easily believe that the earth has been in a state of liquefaction produced by fire, when we consider the nature of the matters which the globe incloses, the greatest part of which are vitrified or vitrifiable; especially when we reflect on the impossibility there is that the earth should ever have been in a state of fluidity, produced by the waters; since there is infinitely more earth than water, and that water has not the power of dissolving stone, sand, and other matters of which the earth is composed.

It is plain then that the earth took its figure at the time when it was liquefied by fire: by pursuing our hypothesis it appears, that when the sun quitted it, the earth had no other form than that of a torrent of melted and inflamed vapour matter; that this torrent collected itself by the mutual attraction of its parts, and became a globe, to which the rotative motion gave the figure of a spheroid; and when the earth was cooled, the vapours, which were first extended like the tails of comets, by degrees condensed and fell upon the surface, depositing, at the same time, a slimy substance mixed with sulphurous and saline matters, a part of which, by the motion of the waters, was swept into the perpendicular cracks, where it produced metals, while the rest remained on the surface, and produced that reddish earth which forms the first strata; and which, according to different places, is more or less blended with animal and vegetable particles, so reduced that the organization is no longer perceptible.

Therefore, in the first state of the earth, the globe was internally composed of vitrified matter, as I believe it is at present, above which were placed those bodies the fire had most divided, as sand, which are only fragments of glass; and above these, pumice stones and the scoria of the vitrified matter, which formed the various clays; the whole was covered with water 5 or 600 feet deep, produced by the condensation of the vapours, when the globe began to cool. This water every where deposited a muddy bed, mixed with waters which sublime and exhale by the fire; and the air was formed of the most subtile vapours, which, by their lightness, disengaged themselves from the waters, and surmounted them.

Such was the state of the globe when the action of the tides, the winds, and the heat of the sun, began to change the surface of the earth. The diurnal motion, and the flux and reflux, at first raised the waters under the southern climate, which carried with them mud, clay, and sand, and by raising the parts of the equator, they by degrees perhaps lowered those of the poles about two leagues, as we before mentioned; for the waters soon reduced into powder the pumice stones and other spongeous parts of the vitrified matter that were at the surface, they hollowed some places, and raised others, which in course of time became continents, and produced all the inequalities, and which are more considerable towards the equator than the poles; for the highest mountains are between the tropics and the middle of the temperate zones, and the lowest are from the polar circle to the poles; between the tropics are the Cordeliers, and almost all the mountains of Mexico and Brazil, the great and little Atlas, the Moon, &c. Beside the land which is between the tropics, from the superior number of islands found in those parts, is the most unequal of all the globe, as evidently is the sea.

However independent my theory may be of that hypothesis of what passed at the time of the first state of the globe, I refer to it in this article, in order to shew the connection and possibility of the system which I endeavoured to maintain in the first article. It must only be remarked, that my theory does not stray far from it, as I take the earth in a state nearly similar to what it appears at present, and as I do not make use of any of the suppositions which are used on reasoning on the past state of the terrestrial globe. But as I here present a new idea on the subject of the sediment deposited by the water, which, in my opinion, has perforated the upper bed of earth, it appears to me also necessary to give the reason on which I found this opinion.

The vapours which rise in the air produce rain, dew, aerial fires, thunder, and other meteors. These vapours are therefore blended with aqueous, aerial, sulphurous and terrestrial particles, &c. and it is the solid and earthy particles which form the mud or slime we are now speaking of. When rain water is suffered to rest, a sediment is formed at bottom; and having collected a quantity, if it is suffered to stand and corrupt, it produces a kind of mud which falls to the bottom of the vessel. Dew produces much more of this mud than rain water, which is greasy, unctuous, and of a reddish colour.

The first strata of the earth is composed of this mud, mixed with perished vegetable or animal parts, or rather stony and sandy particles. We may remark that almost all land proper for cultivation is reddish, and more or less mixed with these different matters; the particles of sand or stone found there are of two kinds, the one coarse and heavy, the other fine and sometimes impalpable. The largest comes from the lower strata loosened in cultivating the earth, or rather the upper mould, by penetrating into the lower, which is of sand and other divided matters, and forms those earths we call fat and fertile. The finer sort proceeds from the air, and falls with dew and rain, and mixes intimately with the soil. This is properly the residue of the powder, which the wind continually raises from the surface of the earth, and which falls again after having imbibed the humidity of the air. When the earth predominates, and the stony and sandy parts are but few, the earth is then reddish and fertile: if it is mixed with a considerable quantity of perished animal or vegetable substances, it is blackish, and often more fertile than the first; but if the mould is only in a small quantity, as well as the animal or vegetable parts, the earth is white and sterile, and when the sandy, stony, or cretaceous parts which compose these sterile lands, are mixed with a sufficient quantity of perished animal or vegetable substances, they form the black and lighter earths, but have little fertility; so that according to the different combinations of these three different matters, the land is more or less fecund and differently coloured.

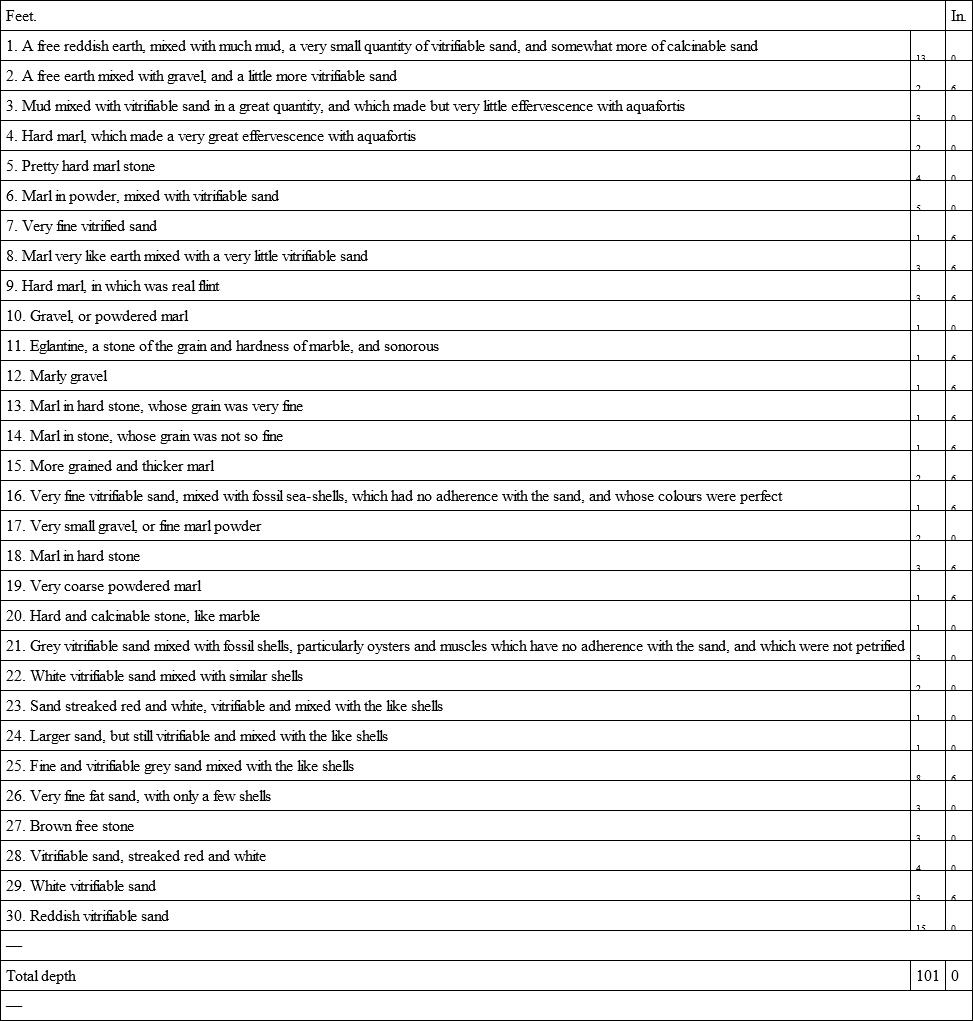

To fix some ideas relative to these stratas; let us take, for example, the earth of Marly-la-ville, where the pits are very deep: it is a high country, but flat and fertile, and its strata lie arranged horizontally. I had samples brought me of all these strata which M. Dalibard, an able botanist, versed in different sciences, had dug under his inspection; and after having proved the matters of which they consisted in aquafortis, I formed the following table of them.

The state of the different beds of earth, found at Marly-la-ville, to the depth of 100 feet.

I have before said that I tried all these matters in aquafortis, because where the inspection and comparison of matters with others that we are acquainted with is not sufficient to permit us to denominate and range them in the class which they belong, there is no means more ready, nor perhaps more sure, than to try by aquafortis the terrestrial or lapidific matter: those which acid spirits dissolve immediately with heat and ebullition, are generally calcinable, and those on which they make no impression are vitrifiable.

By this enumeration we perceive, that the soil of Marly-la-ville was formerly the bottom of the sea, which has been raised above 75 feet, since we find shells at that depth below the surface. Those shells have been transported by the motion of the water, at the same time as the sand in which they are met with, and the whole of the upper strata, even to the first, have been transported after the same manner by the motion of the water, and deposited in form of a sediment; which we cannot doubt, as well by reason of their horizontal position, as of the different beds of sand mixed with shells and marl, the last of which are only the fragments of the shells. The last stratum itself has been formed almost entirely by the mould we have spoken of, mixed with a small part of the marl which was at the surface.

I have chosen this example, as the most disadvantageous to my theory, because it at first appears very difficult to conceive that the dust of the air, rain and dew, could produce strata of free earth thirteen feet thick; but it ought to be observed, that it is very rare to find, especially in high lands, so considerable a thickness of cultivateable earth; it is generally about three or four feet, and often not more than one. In plains surrounded with hills, this thickness of good earth is the greatest, because the rain loosens the earth of the hills, and carries it into the vallies; but without supposing any thing of that kind, I find that the last strata formed by the waters are thick beds of marl. It is natural to imagine that the upper stratum had, at the beginning, a still greater thickness, besides the thirteen feet of marl, when the sea quitted the land and left it naked. This marl, exposed to the air, melted with the rain; the action of the air and heat of the sun produced flaws, and reduced it into powder on the surface; the sea would not quit this land precipitately, but sometimes cover it, either by the alternative motion of the tides, or by the extraordinary elevation of the waters in foul weather, when it mixed with this bed of marl, mud, clay, and other matters. When the land was raised above the waters, plants would begin to grow, and it was then that the dust in the rain or dew by degrees added to its substance and gave it a reddish colour; this thickness and fertility was soon augmented by culture; by digging and dividing its surface, and thus giving to the dust, in the dew or rain, the facility of more deeply penetrating it, which at last produced that bed of free earth thirteen feet thick.

I shall not here examine whether the reddish colour of vegetable earth proceeds from the iron which is contained in the earths that are deposited by the rains and dews, but being of importance, shall take notice of it when we come to treat of minerals; it is sufficient to have explained our conception of the formation of the superficial strata of the earth, and by other examples we shall prove, that the formation of the interior strata, can only be the work of the waters.

The surface of the globe, says Woodward, this external stratum on which men and animals walk, which serves as a magazine for the formation of vegetables and animals, is, for the greatest part, composed of vegetable or animal matter, and is in continual motion and variation. All animals and vegetables which have existed from the creation of the world, have successively extracted from this stratum the matter which composes it, and have, after their deaths, restored to it this borrowed matter: it remains there always ready to be retaken, and to serve for the formation of other bodies of the same species successively, for the matter which composes one body is proper and natural to form another body of the same kind. In uninhabited countries, where the woods are never cut, where animals do not brouze on the plants, this stratum of vegetable earth increases considerably. In all woods, even in those which are sometimes cut, there is a bed of mould, of six or eight inches thick, formed entirely by the leaves, small branches, and barks which have perished. I have often observed on the ancient Roman way, which crosses Burgundy in a long extent of soil, that there is formed a bed of black earth more than a foot thick upon the stones, which nourishes very high trees; and this stratum could be composed only of a black mould formed by the leaves, bark, and perished wood. As vegetables inhale for their nutriment much more from the air and water than the earth, it happens that when they perish, they return to the earth more than they have taken from it. Besides, forests collect the rain water, and by stopping the vapours increase their moisture; so in a wood which is preserved a long time, the stratum of earth which serves for vegetation increases considerably. But animals restoring less to the earth than they take from it, and men making enormous consumption of wood and plants for fire, and other uses, it follows that the vegetable soil of inhabited countries must diminish, and become, in time, like the soil of Arabia Petrea, and other eastern provinces, which, in fact, are the most ancient inhabited countries, where only sand and salt are now to be met with; for the fixed salts of plants and animals remain, whereas all the other parts volatilise, and are transported by the air.