полная версия

полная версияTelepathy, Genuine and Fraudulent

A few words will suffice to describe the experiments which Yoga Rama carried out to show (1) the control he had acquired over the functions of his body, and (2) his insensibility to pain. As has already been stated, he asked two members of the Committee to stand by him and note by their watches the length of time that he was able to cease breathing. He retained his breath for fifty seconds. A member of the Committee at the back of the stage called out, when the length of time was announced, "That is nothing. I can stop breathing for a full minute." This exclamation appeared to disconcert Yoga Rama a good deal. The standing barefooted on a board studded with nails and on broken glass are common tricks which can be seen performed by negroes at country fairs. I felt the points of the nails and found they had been filed down and were blunt. Mr. Marriott sat on the nails to the amusement of the audience while Yoga Rama had gone off the stage to remove his boots. When Yoga Rama returned he stood barefooted on these nails only for about half a minute. He then proceeded to break some bottles on a piece of felt. He pounded away on the glass with a hammer till he had reduced the greater part to nearly a powder. He carefully pushed the larger pieces of glass on one side and stood on the powdered portion.

I will now proceed to state the reasons which lead me to the conclusion that Yoga Rama was able to see, although apparently blindfolded.

1. The bandages were removed from his eyes by Mr. Marriott, who had blindfolded him at the commencement of the performance. While this was being done I had my face about two feet away from Yoga Rama's face and I carefully noted the position of each article as it was being removed. The lower edge of the porous plaster was above the tip of the performer's nose, and the edge of the white handkerchief above the edge of the plaster, and above the edge of the handkerchief was the edge of the crimson scarf. The edges of the handkerchief and scarf were sufficiently high up, so that, had the blindfolding depended only on these, he could have seen under them. The gloves which had been placed on the handkerchief need not be taken into account, as the folded pieces of paper on his eyes prevented them from pressing into the sockets of Yoga Rama's eyes, and he, by merely closing the eyes and bringing the eyebrows well down when he was being blindfolded and then opening his eyes and lifting the eyebrows well up, could displace the gloves from their original position and cause them to rise, as a conjurer well knows; therefore the blindfolding really depended on the position of the porous plaster. Now when Mr. Marriott placed the plaster over the pieces of paper he took care that the lower edges of both pieces should be on one of the lines of holes which existed in the plaster as shown in the accompanying engraving (which is taken from a photograph).

He also took care that the lower edge of the plaster should stick against Yoga Rama's cheeks. On examining the plaster just before it was removed we found that the lower edge no longer stuck against the performer's cheeks. There were hollow spaces between the bridge of his nose and his cheeks through which he could have seen with a downward glance. The point now arises whether he used both his eyes or only one. I noticed that Yoga Rama always kept the right side of his face towards the sitters when trying the experiments. If the reader will look at the engraving, which shows the exact position of the folded pieces of paper at the time of the removal of the plaster from Yoga Rama's face, he will see that the piece of paper which covered his right eye is no longer on the same line of holes as the left piece, but is higher up, and, what is most suspicious, he will note some pieces of tissue paper which were stuck on the plaster by Yoga Rama and were under the pieces of folded paper, which prevented these from adhering to the plaster; thus by an upper movement of the eyebrows Yoga Rama succeeded in raising the folded piece of paper which covered his right eye, and with this eye he glanced under the plaster and watched the movements of the sitter's hands, etc.

2. As I have stated above, Yoga Rama always kept the right side of his head towards the person with whom he was experimenting. He tried one experiment with a gentleman who sat in the second row of the stalls. He then turned his body round so that the right side of his face was in the same position relatively to this gentleman as it had been to the sitters on the stage. Moreover, the lights in the body of the theatre were not alight when Yoga Rama was trying his alleged thought-readings with the members of the Committee on the stage, but when he experimented with the gentleman in the stalls, one of the electric chandeliers in the body of the theatre, not far from the gentleman, was immediately lit, thus enabling Yoga Rama to watch the movements of the gentleman's right hand when tracing the letters of the name he had chosen on the palm of his left hand, and giving the taps corresponding to the number of the letters.

3. At the conclusion of the performance, after the bulk of the audience had left, some persons remained in the foyer of the theatre, and a discussion arose, during which some of the persons present asserted that Yoga Rama had brought about his results by supernormal means. Mr. Marriott, Mr. Guttwoch, and I denied this. At that moment Yoga Rama came into the foyer, and he was accused by us of having been able to see. He asserted that he had not seen, and to prove it offered to try some experiments while a handkerchief was held tightly against his eyes. Mr. Guttwoch held a handkerchief against his eyes. As Yoga Rama was not now able to see, he resorted to a different method from the one he used on the stage. He held the wrist of the left hand of a lady with the thumb and three fingers of his right hand, while his forefinger rested against the back of the lady's hand. He then asked her to trace the letters of the name thought of with the forefinger of her right hand on the palm of her left hand, which was being held by him. He was able to tell the name, but only after repeated tracing of the letters by the lady. Yoga Rama not being able to be guided by sight as in his stage performances, now guided himself by the sense of touch. Although I have never before carried out an experiment of this nature myself, when Miss Newton and I returned to the rooms of the Society for Psychical Research I tried the experiment with her. I closed my eyes and held her wrist, and was able to feel the letter which she traced on the palm of her hand. Manifestly this is a difficult trick to perform, and requires great practice. I noticed that Yoga Rama chose the hand of a lady in preference to that of a gentleman, obviously because a lady's hand is thinner than that of a man, and the motion of her finger would be more easily felt.

What convinced me more than any of the above reasons that Yoga Rama was able to see during his performance is the following fact. I placed the sticking plaster over my eyes after it had been taken from Yoga Rama's eyes and, to my surprise, I found I could perfectly well see through it. The numerous small holes with which it was perforated allowed me to do this.

The audience at the "Little Theatre" had had their expectations raised that they were to witness manifestations of the occult powers of the mind through the mediumship of an Abyssinian Yogi, instead of which they witnessed an ordinary conjuring entertainment by a man who previously to assuming the name of "Yoga [sic] Rama" was known as Professor A. D. Pickens of Conduit Street, London.

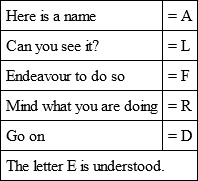

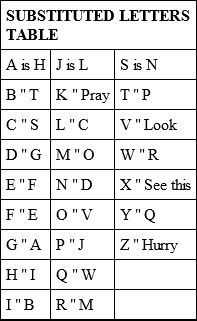

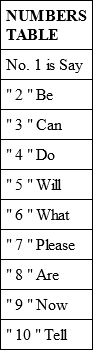

Besides the method used by Yoga Rama for producing his so-called thought transference, there are others resorted to by public entertainers. The one most in use is by means of a verbal code. The letters of the alphabet are substituted and a word can be conveyed by the agent asking a series of questions, each question beginning with a substituted letter. The percipient has to remember what letters the substituted ones represent; he takes note of the first letter only of each question, puts them together in his mind, and thus gets the word that it is the intention of the agent to convey.

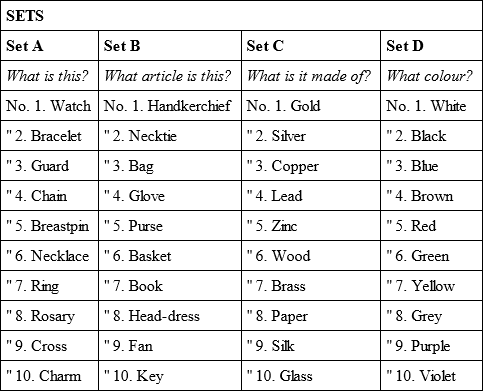

I have made a table (shown opposite) which shows one of these systems.

If the name "Alfred" is to be conveyed, it can be done by the following questions: —

TABLE

The transmission of the nature of an article is by dividing articles that would be likely to be brought to a public entertainment into sets of ten, each set being indicated by a different question. These sets have to be learned by heart by the agent and the percipient. I give in the table four sets to illustrate my meaning. After asking the question which conveys the set to which the article belongs, a second question is asked, beginning with the word corresponding to the number on the number table. This will indicate what number in the set the article corresponds to. As an example: when the question "What is this?" is asked, it means that the article corresponds to Set A. If the second question begins with "Do," such as "Do you know?", this question on referring to the number table would mean No. 4; therefore the article would be a chain. Now, if the question "What is it made of?" is asked, it would refer to Set C, and if this question is followed by "Can you tell me?", on referring to the number table it will be found to correspond to No. 3; therefore the article would be a chain made of copper. When an article is not in any one of the sets the substituted letter code is used. Of course public entertainers learn by heart a number of sets, not only four.

For silent thought transference occasionally electrical contrivances are resorted to. These are placed in different parts of the hall, and when being pressed by the foot or hand of the agent will convey a message to a certain part of the stage upon which the percipient (who may be blindfolded) rests his foot.

There is another silent method which can be worked by a confederate who is placed behind a curtain close to the chair on the stage upon which the blindfolded percipient sits. The confederate watches the performer who stands amongst the audience and reads through a spyglass what he is writing on his tablet when putting down what members of the audience wish to be done. The confederate then communicates the contents of the writing to the percipient on the stage by whispering or by an electrical apparatus. The position of the performer or agent while he is writing in a clear hand on his tablets with his back to the stage easily enables a confederate to read the writing.

Then there is the silent method of a French conjurer, some of whose performances I have witnessed, which consists of suggesting or "forcing" the spectators to do certain things, each action having a corresponding number which he conveys to his lady assistant, who is blindfolded, by touching her foot with his after she has come down from the stage and stands by his side amongst the audience.

The "time-coding" method consists of silently counting by the agent and percipient at the same rate, starting from a preconcerted signal and ending at another preconcerted signal. The performer amongst the audience has in his hand a piece of paper on which is written the number that he wishes to silently convey to the other blindfolded performer on the stage. At the moment that he bends his head to look at the number he begins silently counting at a certain rate; a confederate behind the scenes begins counting at the same rate from the moment that the performer bends his head. When the performer lifts his head he ceases counting, so does the confederate. Each number written on the paper is thus conveyed, and the confederate communicates the total to the blindfolded performer by means of an electrical apparatus or otherwise.

I have attended several performances in public halls in London at which thought transference – so-called – was carried out by the above trick methods.

Sir Oliver Lodge was present with me at one of the performances at which the time-coding method was used. He has sent me the following note: —

"I was with Mr. Baggally on one of these occasions, and took note of the fact that he could often guess what was being transmitted by the performers quite as well as they could themselves. We sat in a box looking at them, and he often told me before they had spoken what they were going to say (or words to that effect).

"I perceived even without his assistance that the performance, which was stimulated by the success of the Zancigs, was an exceedingly inferior imitation of what they had achieved, and was manifestly done by a code of some kind.

"O. J. L."Some of the methods resorted to by public entertainers are so ingenious that the spectator is led to believe that genuine thought transference has taken place. The following correspondence, which appeared in the spiritualistic weekly paper called Light, illustrates a case in point. In the number of Light of the 25th October 1902 there appeared this letter headed "Thought Transference": —

"Sir, – A few years ago Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin gave the following entertainment in almost every large town in the three kingdoms. The public were invited to write any question or questions they desired to have answered on a piece of paper, to place it in their pockets, and keep it there without communicating its contents to anyone, and then when they went to the hall their names were called out and their question answered without the papers leaving their possession. About fifty such inquiries were answered each evening without a single failure by Mrs. Baldwin, who sat blindfolded with her back to the audience. From my experience and that of my friends, collusion was impossible, and the only way of accounting for the performance was by thought transference or telepathy between Mrs. Baldwin and those of the audience with whom she was in mental sympathy.

(Signed) "C. A. M."Commenting on this letter, I wrote to Light, and my communication appeared the following week. It was to this effect: —

"Under the heading of 'Thought Transference,' your correspondent, C. A. M., gives an account of some entertainments by Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin, at which he says" (I here quoted from C. A. M.'s letter, and then continued as follows): – "I never was present at entertainments given by Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin, and therefore cannot express an opinion as to the modus operandi in their particular case, but I would point out that their entertainments bear a close resemblance to those given by conjurers. The explanation of the mystery in a conjurer's case is as follows: – The conjurer asks members of the audience to write their questions secretly, to sign their names at the bottom of the question, and then to fold the pieces of paper on which the questions are written and place them in their pockets. To facilitate the writing he hands pencils round and tablets upon which to rest the pieces of paper during the writing of the questions, or the members of the audience, if they so wish, can retire into an adjoining room and write their questions on a table. The tablets and pencils are then collected by an assistant who is a confederate, who then retires from the hall to the room where the table is. The tablets and table have false surfaces of leather or other material, which, on being removed by the confederate, disclose a layer of carbon paper resting on another of white paper upon which the questions have been recorded unknown to the inquirers. The confederate then proceeds to read the questions with their respective attached signatures, and to communicate them to the blindfolded medium by an electrical apparatus upon which the medium's foot rests, or by other mechanical means."

I signed my letter W. W. B. A fortnight after, the following letter appeared in Light: —

"Sir, – With reference to the communication by W. W. B. referring to the supposed thought transference, and mentioned by another correspondent, C. A. M., in connection with the entertainments of Professor Baldwin (an American conjurer and brother mason), whom I met in Cape Town on two separate occasions, permit me to state that (1) if it is the same Baldwin, he is one of the cleverest illusionists in his special line of trick thought transference, and W. W. B. is quite right. (2) I know that Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin did most of their experiments by trick, because, being one of the chosen committee to test the so-called thought reading, I fixed it absolutely as trickery on the lines indicated by W. W. B.

(Signed) "Berks Hutchinson"I was gratified to read this letter and to find that my conjecture was correct that the Baldwin performance was a mere exhibition of conjuring.

PART III

THE ZANCIGS

Some years ago there appeared at the Alhambra Theatre, London, two entertainers – Mr. and Mrs. Zancig – whose performances were of so puzzling a nature that to many who had witnessed them the only explanation of the results obtained appeared to be that genuine telepathy was at play. The Daily Mail newspaper arranged that Mr. and Mrs. Zancig should be subjected to a series of severe tests at its office, and on the 30th November 1906 these were carried out.

On the 1st December the Daily Mail published a full account of these experiments. The publication of this and of other accounts by persons who had witnessed the remarkable performances of the Zancigs led to a heated controversy between the correspondents of the Daily Mail and the Daily Chronicle. Those of the first paper mostly asserted that the performance was an exhibition of true telepathy, while those of the second paper declared that codes – visual and verbal – would account for the phenomena. Previously to the experiment carried out by the Daily Mail I had obtained a letter of introduction to the Zancigs from a friend of mine who had had private tests with them, but as it was necessary to have the permission of the manager of the Alhambra before an interview with the Zancigs could be arranged, I called at the offices of that theatre, and saw Mr. Scott, the manager. I informed him that I was a member of the Society for Psychical Research, which body I told him took the deepest interest in telepathy. I handed him a letter that I had written to Mr. Zancig, and on the 29th November 1906 I received the following communication from the last-named gentleman: —

"Dear Sir, – I received a letter from Miss H. A. Dallas, telling me that you would like to meet us. Now, my dear sir, we would be pleased to make your acquaintance, and have you call for a visit, but if it is for any private show and to be tried and judged if our work is, as we represent, 'two minds with but a single thought,' I will have to say No. We have done nothing since we arrived in London but have callers to test and try us every day, from three to four ladies and gentlemen. My wife and I agreed to all tests they put to us, and all was quite satisfactory. Personally I do not care, but it has been quite a strain on my wife. Should you care to witness our show, you would be able to see us at ten p.m. on the Alhambra stage, but if you care to call and see us, and have a little talk, we both would be pleased to meet you. – Trusting that I am understood, I remain, yours sincerely,

(Signed) "Julius Zancig"Although the contents of the above letter were of a discouraging nature, I determined to strike the iron while it was hot; therefore, on the evening of the same day I called, accompanied by my wife, at the flat where the Zancigs resided. They were at the time partaking of their evening meal. We apologized for our intrusion, but by the kind way that they received us we were soon put at our ease. I informed Mr. Zancig that I was much interested in telepathy, and that I had personally carried out experiments in this branch of psychical research, and that I was assured of the truth of its existence through the successes that I had obtained.

Mr. and Mrs. Zancig impressed my wife and myself most favourably by their unaffected and simple manner. After a conversation which lasted about ten minutes, Mr. Zancig very kindly spontaneously offered to try some experiments. I will now describe these. Madame Zancig went to the other end of the room farthest away from where Mr. Zancig, my wife, and I sat. She faced the wall with her back to us; Mr. Zancig then wrote with a chalk a line of figures on a slate which he held in his left hand, and called out the word "Ready." Madame Zancig immediately named the figures correctly and in their proper order. The same kind of experiment was tried successfully three times. The results might have been due to telepathy, but I was not satisfied, as it could have been possible that the figures were prearranged, or that Madame Zancig could tell by the sound of the chalk what figures were being written. I also had in my mind the fact that there is a method of communicating figures by time-coding.

Mr. Zancig then asked me to write a double line of figures. I handed the slate to him, and after he had called out "Ready" Madame Zancig proceeded to cast them up correctly.

As Madame Zancig named all my figures aloud as she was summing them up, this experiment was of a more complicated nature than the previous ones; nevertheless, I was not entirely satisfied, as time-coding in putting down the resultant figures by Mr. Zancig, and the hearing of the sound of the chalk by Madame Zancig when I was writing my own figures, might have accounted for the favourable result.

To prevent the possibility of communicating by an electrical or other apparatus concealed under the carpet, I requested Mr. Zancig to raise his feet from the floor. He immediately complied by sitting on the table, where he remained to the last experiment.

Madame Zancig then retired into an adjoining bedroom with a slate in her hand; the door was closed, but not entirely. My wife wrote down two lines of figures, the slate was handed by her to Mr. Zancig, who called out "Ready," and he then proceeded without speaking to add them up. Madame Zancig then came into the room with the correct result written by herself on her slate. This was a more crucial test than the last, but still, although visual-coding was excluded, sound-coding while Mr. Zancig was writing the resultant sum was not entirely so.

Then followed the experiment of transmitting a selected line in a book. Mr. Zancig handed me a book and asked me to open it at any page and to point out a line. After I had done so I handed the book to him. He called out "Ready." Then his wife opened a duplicate book at the proper page, and read the line which I had selected. Doubtless the words of the line were not communicated telepathically or otherwise by Mr. Zancig, but only the number of the page and the number of the line counting from the top of the page. Nevertheless, it was difficult to discover by what method this was done, as Mr. Zancig simply called out "Ready." There did not appear to be time for the numbers of the page and line to be transmitted by time-coding. The reader will observe that as the experiments proceeded they appeared to present increasing evidence that true telepathy was at work.

The following and last experiment that I tried on this occasion was the most crucial. I requested Mr. Zancig to go out with me on to the landing outside the door of the flat. I did not previously inform Madame Zancig nor Mr. Zancig of the nature of the test that I was about to put. Madame Zancig remained in the room with my wife. The door was closed, but not completely. When we were on the landing I suddenly drew my cheque-book out of my pocket, tore out a cheque, and handed it to Mr. Zancig, requesting him to transmit the number. Mr. Zancig observed to me in a whisper that the noise of the traffic in the street was very disturbing. This was true, as the hall door to the street was open. He then remained silent while he looked at the cheque. My wife then came out on to the landing, and handed me a slate upon which Madame Zancig had during the experiment written the words, "In the year 1875." Mr. Zancig then said aloud, "This is not what we want; it is the number." My wife returned into the room with the slate, and the door was closed, but not completely. It was impossible, however, for Madame Zancig to see her husband. The suspicion arose in my mind that the number on the cheque might have been communicated to Madame Zancig by the words that Mr. Zancig had spoken aloud. I therefore took the cheque that he had in his hand and substituted another one with a different number that I tore from the bottom of my cheque-book. Mr. Zancig remained absolutely silent during the whole time that this second experiment lasted. My wife again came out of the room with the slate, upon which Madame Zancig had written quite correctly, in their proper order, four of the five numbers of the second cheque, with the exception of the last figure, which was wanting, but just as we were returning to the room Madame Zancig said, "There was another figure; it was four" – which was correct. This impressed me as a good test, with regard to the three last numbers of this cheque, which were different from the corresponding ones of the first cheque. Madame Zancig could not see her husband, and he remained absolutely silent while the experiment was being carried out.