полная версия

полная версияLiving on a Little

"What forfeit?" asked Dolly.

"Why, we have an arrangement that Dick can bring any friends home to dinner at any time, the number not to exceed two at once," explained her sister. "Then if there is dinner enough, and if it really is good enough for the occasion, he has to pay me for my extra trouble. Of course, if I ever fail, I'll have to pay up in my turn, but so far he has been caught every time. Dolly and I will consider, Dick, what the forfeit shall be. Matinee tickets, I rather think, this time."

"Well, I'll get them cheerfully, for that was really a good dinner, and the kind a man likes, which is another matter."

The next day Mrs. Thorne replaced the soup, cheese, and peas she had taken out of her emergency closet. She had also to buy extra meat for dinner as there was none left over for a second day's meal, but as the dinner had been a cheap one for five, she did not grudge the small amount expended. "But now we must economize in earnest this week," she said as she added up her accounts, "because next week I want to have a real little dinner-party. I must have several, in fact, to return the hospitality shown you, my dear. Luckily it is spring, now; remember that it is always cheaper to entertain in spring than at any other time in the year."

"It's a lot cheaper not to entertain at all," Dolly grumbled rebelliously. "Don't let's have any dinner-parties – they're such a bother!"

"On the contrary, they are no bother at all, but lots of fun when you have them as I do, simply and inexpensively. And you really must do some entertaining in your turn if you do not want to drop out of everything when you are married, and that would be a most foolish thing to do."

"Who waits on the table?" demanded Dolly.

"Oh, that's the trouble with the dinner-party, is it? Well, I hasten to relieve your mind – you don't! When I give a company dinner I have in a young girl whom I have trained. She does all the waiting, and stays and washes the dishes, and I pay her seventy-five cents for the evening. Sometimes, when I have a little luncheon I do my own waiting, and of course in a surprise-party dinner I have to also, but not when I give a regular invitation dinner. I wait till I have money enough in hand for the waitress as well as the food and flowers and all, and then I go ahead."

A few days later the party was arranged for. A young couple and their unmarried brother were asked, making a group of six to sit about the round table. This was the menu Mrs. Thorne wrote out:

Cream of beet soupRadishes, almonds, olivesForequarter of lamb, stuffed; mint jelly; new potatoes; peasLettuce and cheese balls; wafersVanilla ice-cream and sherried cherries; small cakesCoffee"Doesn't that sound good?" she asked, surveying the paper with her head on one side.

"Now to make as many things as possible to-day, so we won't get too tired to-morrow. First, we will salt the almonds."

"Do let me do those all alone! I saw somebody do it once, and I know exactly how. You just take off the skins and fry them in olive oil."

"My dear, I hate to seem unappreciative or hurt your little feelings, but the fact is, that is a most abominable way to do them, though it's common enough. It makes them greasy and streaky, partly brown and partly white. This is the really-truly way to make them: first you put them in boiling water till the skins loosen, and then drop them in cold water; slip off the skins, and dry them and mix them with the half beaten white of an egg – that is, about half the whole white; then you sprinkle them with salt and put them on a tin in the oven and occasionally stir them. They will turn a lovely creamy brown and will be crisp and evenly colored, and you can keep those you do not use at one dinner and heat them up to freshen them when you need them, for a second dinner, just as you do crackers. We will do them that way to-day. Then besides that we will get the dining-room in order, polish the silver and glass, fill the salts, and look over the china and table linen, so that to-morrow there will not be much to do."

The next morning the marketing was done early, so that the things would come home in good season. At the grocery they bought the beets, – one bunch of old ones, not the young ones just in market; a can of small American peas; a head of lettuce; a square cream cheese and a round one half its size in order to have enough; a little American cheese; two lemons, and a pint of cream.

At the butcher's they ordered lamb. "Not what you call 'spring lamb,'" she explained, "but exactly what you have been selling all winter; that is still nice, and plenty young enough. Now cut off the neck and the trimmings, and take out the shoulder-blade and make a pocket for the stuffing to go in comfortably, and send me a bunch of mint with it all." While she waited for her change she told Dolly about this purchase. "Forequarter of lamb is really the cheapest roast there is. Sometimes even when we are all by ourselves I buy it and make ever so many meals of it. I get a big piece, as much as eight or nine pounds, because that is the cheapest way, and the butcher keeps it for me and lets me have it as I want it. The roast makes at least two dinners, and there is a lot left over still for croquettes and soufflés and such things. Then there are four chops for one or even two dinners more for two people – "

"'With a good filling soup to take off the edge of the appetite first,' otherwise the four chops would make only one dinner," interrupted Dolly, quoting freely.

"Exactly. And besides, there are the trimmings and odds and ends for meat pies and stews, so you see how far it goes."

"Really, I should think you and Dick would fairly bleat!"

"Well, perhaps we might if we deliberately sat down to lamb night after night, but we don't do anything half so foolish. We have things between, veal and beef and pork, and as the lamb is practically in cold storage at the butcher's, it can wait indefinitely, and when we do have it we live on what I used to think the old Jews wanted to live on in Canaan, – 'the fat of the lamb!' But now's let's hurry home, for there's lots to do yet."

As soon as their things were taken off and kitchen dresses put on, the plain vanilla ice-cream was frozen and packed away to ripen. For the sauce which was to be put on each glass which it was served, a small can of preserved cherries was opened and drained; the juice was boiled down to a thick syrup with a small cup of sugar, and the cherries put back in it to cool, with a flavoring of sherry.

The salad was made next, the lettuce washed and rolled up in a clean towel and put where it was very cold, to crisp. They rolled balls of cream cheese, wetting them with a bit of oil to make them smooth, and adding salt and a dash of cayenne; as each one was made it was rolled in grated American cheese and then laid away. The French dressing was also made, and at the last moment was to be poured over the lettuce, and the golden, white-centred balls laid on it.

The beets for the soup were next chopped and boiled in a pint of water; as much milk was added, the whole seasoned with a slice of onion, salt and pepper, and then strained and slightly thickened. This made the prettiest of pink soups, and one which could be set away and be reheated at dinner time in three minutes. The mint jelly was also made: a cup of water was put with the juice of a lemon and heated; when hot, a small bunch of bruised mint was put in and simmered for two minutes; then this was strained and a level tablespoonful of gelatine, dissolved in half a cup of cold water, was put in with a tiny bit of green vegetable coloring, the whole strained through flannel and put into a pretty little mould. It would come out a lovely sparkling green, quite decorative enough to be put on the table, and delicious to eat with the lamb, Mrs. Thorne assured Dolly complacently.

The peas were turned out of the can, drained, seasoned and made ready to heat up quickly. The potatoes were boiled and cut up in a very little thick white sauce, and a spoonful of parsley was minced to be scattered over them, last of all.

After their luncheon the dinner table was laid. It had a white damask cloth, and a white, lace-edged centrepiece. There were four glass candlesticks with yellow candles and shades, and in the middle a bowl of the yellow jonquils, now in season and inexpensive. At each place was a pretty plate, which was to remain on till exchanged for a hot one later, and a small array of silver, with a tumbler and napkin. The latter hid a dinner roll, so no bread and butter was served at the dinner. The table was then finished except for the last touch; the small dishes of radishes and salted almonds, and a few white peppermints, were to be put on just before dinner, with the dish of mint jelly.

After the dinner was over Dolly confessed her amazement.

"I 'never did,' as the children say. I had no idea you could have so nice, so pretty a party with so little to 'do' with. Really, we never missed the fish, or the entrée, or the game or anything else. It was a lovely and delicious meal, wasn't it, Dick?"

"Modesty compels me to refrain from saying what I truly think, Dolly. Otherwise I should mention my conviction is that it was as good a dinner and as nice a party as you'd often find, and your sister is about as fine a cook and manager as they make 'em. But as I said to begin with, in my position of host my lips are sealed."

"So little trouble, too," Dolly went on, smiling at him. "I really thought you were crazy to ask the Osgoods, whom everybody is afraid to entertain because they have everything in the world, but our dinner was just as nice as though we had followed in their footsteps and had a table decorated with orchids, and whitebait and fancy ices and everything else to eat. Mary, permit me to say I consider you a genius!"

"Nothing of the sort. I am simply a woman, more or less sensible, I fondly trust, who knows that nowadays nobody cares for long, ten-course meals, and if what is set out is only good of its kind, that is all that matters. Then, too, when we are really living on a little and everybody knows it, either we cannot entertain at all, which means that we cannot accept invitations, or we must do it in a plain way, in keeping with the general style of our home life. Anything else would be absurd, snobbish and extravagant. And to prove that people like to come to simple dinner-parties like ours, I shall have two more right away."

"Three cheers," said her husband calmly.

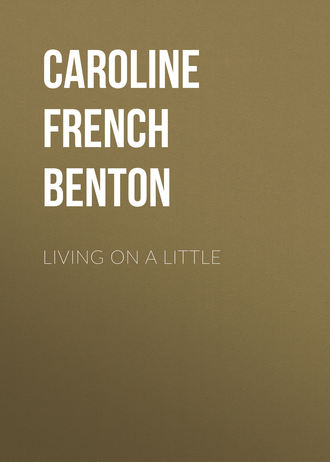

The next morning the sisters added up their accounts and set down the dinner menu and what it cost in a little dinner-party book which was often used for reference by them. This is what the dinner proved to have cost:

"That is all, except the flowers, which were forty cents, and the cherries, which I made myself last summer and paid for then, so I did not have to put their cost in now, you see. The little bottle of olives cost ten cents; so did the radishes. The Jordan almonds were forty cents a pound, and I got half a pound and have some over for next time. With the flowers, that makes the dinner $3.15; say $3.25, to allow a liberal margin for little bits of butter, sugar, salt and so on used up in cooking, and $4, including the pay of the waitress. I call that a cheap party."

As soon as finances permitted and small economies had made the two sisters feel comparatively rich, they gave a second dinner. This time they found some pink tulips at a small florist's, and these they used in making a lovely table. They stuck them one by one into a very shallow dish filled with sand, the leaves put in and out also, and the edge of the dish concealed with moss; this gave exactly the effect of a little bed of growing flowers.

The menu was quite different from the other dinner:

Cream of almond soupOlives, radishes, salted nutsMaryland chicken with cream gravy; new potatoes; corn frittersLettuce and cherry salad; crackersVanilla ice-cream with strawberriesCoffeeThe soup was made by chopping a quarter of a pound of almonds and simmering them in a pint of milk; then the other pint was put in with the seasoning, and it was slightly thickened, strained, and at last beaten up well with an egg-beater to make it foamy. The chicken was cut up and the best pieces dipped in batter and fried in deep fat; a rich cream gravy was passed with this. The corn fritters which were the necessary accompaniment of the dish were made of canned, grated corn.

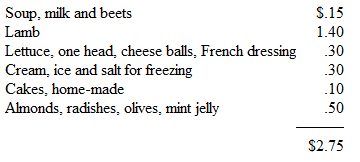

The salad was very cheap at this time of year. Large California cherries were stoned, laid on lettuce, and a French dressing poured over all. The ice-cream was a nice vanilla, and on each glass was put one fine large strawberry. The next day the remains of the chicken appeared at dinner in the shape of croquettes, with a rice border, and the rest of the box of berries came on also. This materially reduced the expenses of that meal, and the difference went on to the cost of the party dinner, to help out. The account was like this:

Adding the little things as before, the flowers, nuts, olives, pay of the waitress, and a margin, brought this up to a trifle over four dollars.

"That is too much," said Mary soberly, as she set down the figures. "I mean to keep strictly within a four-dollar limit. So our third dinner, Dolly, must be less than these and even things."

This was the third dinner:

Clear soup with tapiocaSalted nuts, radishes, almondsRoast of veal, stuffed; fresh mushrooms; potatoesLettuce with chopped nuts; French dressingStrawberry icesCoffee"That is a good, sensible dinner," said Dolly. "No frills, unless you count the mushrooms."

"It is the cost of the waitress that makes these dinners so expensive," said her sister. "It provokes me to have to put money on that, yet I will do it at a real dinner-party. But as for the rest, this ought not to be a costly affair."

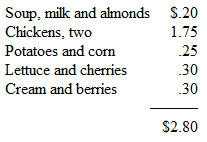

The soup was made of very ordinary materials, but it looked and tasted well. The roast was crisply browned and juicy within, and the delicious stuffing and broiled mushrooms were substantial and good. The salad was lettuce covered with chopped almonds put on after the French dressing. The ices called for no cream and so were inexpensive. The figures showed this result:

"Ah, that's better," said Mary, when she saw the total. "Then the flowers were the same as before, only red instead of pink tulips; the waitress, too, and the margin – only $3.25. I feel relieved."

"Of course roast veal is not quite as good as Maryland chicken," said Dolly, "but the mushrooms made it seem quite elegant; broiled mushrooms are certainly food for the gods. It is quite a saving to have an ice instead of an ice-cream, isn't it? And Mary, did you see what a big, big piece of roast was left over?"

"That is one of the good things about veal, that there is so little waste. I am sure we can easily make two dinners out of it, and that will save ever so much. And when we can get ahead at all, Dolly, we must hurry and have our luncheons."

CHAPTER X

Reducing Expenses

"I never feel as extravagant as I do in spring-time," Mrs. Thorne said as she hovered over asparagus, tiny new potatoes, fresh peas and strawberries in the market one May morning. "Everything is so tempting, and we are tired of winter vegetables, and yet we will run up dreadful accounts if we attempt to have any of these goodies. Come right along, Dolly; don't linger a moment longer, or I am lost."

"You could really have bought a spring vegetable or two," remonstrated her sister as they walked home. "We are ahead on our money, I know, because I rattled the bank this morning, and it was nearly full. I do not see why you did not get something nice and springy if you wanted to."

"Because now for a week or two I mean to reduce expenses. I want to give three small luncheons and have everything as nice and pretty as possible, and you know we used up our savings of two months on our dinner-parties. The rattling of the bank meant only pennies, my dear; I know, for I peeked. So we must cut down vigorously."

"That is an absolute impossibility," said Dolly with decision. "We do not waste a single crumb now, not a potato paring, not a bone nor even an egg-shell. We can't save a cent's worth."

"Oh, yes, we can; we can save a lot if we try. And there is a suggestion for to-day's lesson; it will be on Retrenchment."

Dolly still looked unconvinced when she sat down with book and pencil, but Mary was complacent.

"Of course we do not waste anything," she began, as she took her seat in the sitting-room after the entire apartment was in immaculate order and lunch under way, "and as you suggest, we have cheap meats and vegetables right along. But we can still find some things that are cheaper still, – because you always can, whatever you have. So if we cut down on those to begin with, and have desserts for a week made without butter or eggs, and abandon fruit altogether for the time, I am sure we can have quite a surplus presently.

"To begin with meat, because you know my theory that that is always the expensive point in housekeeping, you know I said veal was cheap in the spring. So it is, but instead of using the ordinary cuts, you can have something less expensive. There is a calf's heart, for one thing. A country butcher would probably give that away – and incidentally inquire what on earth you wanted it for. Here in town I suppose we must pay something for it, but it will not be much; only a few cents. You have no idea what a delicious meat that is, so delicate and tender. You wash it well and make a bread-crumbs stuffing for it with a good deal of seasoning, and after you cut out the strings and wipe it dry in the middle you stuff it. Bake it in a covered pan for two hours, basting it well frequently, then make a gravy and pour over it. You really should have cooked onions, browned in this gravy, to go with the dish, because they are the accepted thing with the heart, but you need not if you do not want to, for it will be good without them. Then the next day you will have enough left over for a dish of baked hash, or a cottage loaf. And all for, say, ten cents or less! Isn't that a stroke of economy?

"Then there is boiled calf's head. That, too, you could get for a song in the country. Have the butcher clean it well and let you have both the brain and the tongue; be sure and make him understand that. Wash and parboil both of these in separate saucepans. The brains taste exactly like sweetbreads, and if you chop them and make them up into croquettes, no one will suspect that they are not what they seem. It is strange that so many people are prejudiced against using brains, for they are the cleanest possible meat. They are kept shut up in a little bone box where nothing can soil or hurt them, and as a calf has little intelligence, they never grow tough from use! So have the brains for one meal. Then when the tongue is tender, take it up and peel it and braise it with minced vegetables; that is, cook it in the oven in a covered pan, smothered in vegetables. Have this as it is, as a roast, and what is left over make up into a loaf exactly as you do with chopped veal or beef; or dice, cream and bake it for a second dinner. If you have any tiny bits still left, put those through the meat chopper and spread them on toast; put an egg on each and serve for breakfast or luncheon.

"Then the head proper. This you had better have the butcher keep for you till you have used up the other things, or you will have too much meat on hand to use economically. When he sends it, tell him to split it open, as this must be done and you probably could not do it yourself. Put it into cold water and put it on the fire till it comes to the boiling point. Take it off and plunge it into cold water to blanch it, rub it all over with half a lemon, and then put it into boiling water, only just enough to cover it, and add a tablespoonful of vinegar, a small onion, chopped, a carrot and a sprig of parsley. If you have a bay leaf, put that in too. Cover the pot and gently simmer it for two hours, or till the meat is ready to drop from the bones. Take it up then, take out all the bones, skin, and gristle, and put the meat in an even pile; cover it with bread crumbs and brown it in the oven. In cool weather this will make two good dinners, and you will find it as good as the tongue. In summer, divide the meat and have only one dinner baked. Put the other half into a mould and fill it up with the stock it was boiled in, after you have cooked this down and strained it; it is so full of gelatine that it will set at once and you will have a fine dish of ice-cold meat set in a clear aspic, and what better could any one wish for? If there is more stock than you need, keep out part for the basis of a soup; it is so strong that it will make you an extra good one, with perhaps tomatoes added to it. Now when you consider that one calf's head will make at the very least four dinners for a small family, do you not think by having it you will materially reduce expenses?"

"Having a mind open to conviction, I do."

"Well, then! To go on to another sort of meat, here is another suggestion of cheapness. You know what a shin of beef is, don't you? The lower part of the leg, where the meat is apt to be stringy and tough; most people think it is good only for soup. Get the butcher to cut you two rounds from that, right through the bone. Perhaps you may need three, if he cuts low down, or possibly only one high up; you must watch him and judge how many you will need. Take this, put it in a casserole or stew-pan with hot water enough to cover it and put it on the very back of the stove, where it cannot boil, and let it stand there for three hours; then try it, and if it is tender, cover it with chopped vegetables, carrots, a little onion, parsley, and turnips and peas if you happen to have them at hand. Let it simmer now for an hour. Take up the meat, drain the vegetables and put them around it, thicken and brown the gravy and put it over all, and you would never guess you were dining off 'soup meat.'

"Or, here is another way to cook the same cut. Get a good large piece, say one weighing two and a half pounds. Brown it in a hot saucepan all over with a spoonful of drippings; when it is all a good color, pour enough water on to just cover it, and put in the vegetables as you did before and add six cloves. Simmer the whole under a cover for four hours and serve just as it is, in a hot dish.

"Still a third way to manage, is to cut the meat from the bone and dice it. Simmer this with the vegetables and the bone till it is very tender. Take up the meat and put it in a baking-dish, and strain and thicken the gravy and pour this over; then put a crust on top, either one of pastry or a mashed potato crust with an egg beaten in it to make it light, and bake the whole. Put a little butter on top to brown it if you use the potato. Now, no one who ate those three or four dishes would think they were related; but when you have them, do not serve them one after another, but let a week go by between, just to have a change of meat.

"Then there is calf's liver. That in town even in spring costs more than it did some years ago, but even here a little goes so far that I call it a cheap meat, too; there is not a particle of waste about it, you see. Get a pound and a half some time and lard it; that is, stick narrow strips of salt pork in it. If you cannot do that, lay two slices on top of the whole. Bake it in a covered pan and baste it often, and serve with a brown gravy. There will be one dinner off this roast to begin with. For a second, chop it up and either make a mock terrapin by a cook-book rule, or else cut it in dice, cream and bake it. If any bits are left over have those on toast for luncheon."

"Mary, you told me in the most solemn manner that I was never to have meat for either luncheon or breakfast."

"Did I say never? I did not quite mean that, because sometimes you have a very little bit of something you can economically utilize in that way. Of course you could have it in a soufflé for dinner if you had a small cupful, but if you had only half as much, you could not; then put it on toast and add plenty of gravy, and have it for breakfast with a clear conscience. Only do not have anything which would do for dinner; that is all I meant by my 'never.' The same thing applies to lunch. If you have just a little meat you are sure is useless elsewhere, mix it with boiled rice and lots of seasoning, and bake it in a mould in a pan of water and turn it out hot; that makes a very good and economical dish for once."