полная версия

полная версияRuins of Ancient Cities (Vol. 2 of 2)

“All the implements that Belzoni had for removing this colossus were fourteen poles, eight of which were employed in making a car for the colossus, four ropes of palm-leaves, four rollers, and no tackle of any description. With these sorry implements and such wretched workmen as the place could produce, he contrived to move the colossus from the ruins where it lay to the banks of the Nile, a distance considerably more than a mile. But it was a no less difficult task to place the colossus on board a boat, the bank of the river being ‘more than fifteen feet above the level of the water, which had retired at least a hundred yards from it.’ This, however, was effected by making a sloping causeway, along which the heavy mass descended slowly till it came to the lower part, where, by means of four poles, a kind of bridge was made, having one end resting on the centre parts of the boat, and the other on the inclined plane. Thus the colossus was moved into the boat without any danger of tilting it over by pressing too much on one side. From Thebes it was carried down the river to Rosetta, and thence to Alexandria, a distance of more than four hundred miles: from the latter place it was embarked for England.

“The material of this colossus is a fine-grained granite, which is found in the quarries near the southern boundary of Egypt, from which masses of enormous size may be procured free from any split or fracture. These quarries supplied the Egyptians with the principal materials for their colossal statues and obelisks, some of which, in an unfinished form, may still be seen in the granite quarries of Assouan. There is considerable variety in the qualities of this granite, as we may see from the specimens in the Museum, some of which consist of much larger component parts than others, and in different proportions; yet all of them admit a fine polish. The colossal head, No. 8, opposite to the Memnon, No. 2, commonly called an altar, will serve to explain our meaning.

“This Memnon’s bust consists of one piece of stone, of two different colours, of which the sculptor has judiciously applied the red part to form the face. Though there is a style of sculpture which we may properly call Egyptian, as distinguished from and inferior to the Greek, and though this statue clearly belongs to the Egyptian style, it surpasses as a work of art most other statues from that country by a peculiar sweetness of expression and a finer outline of face. Though the eyebrows are hardly prominent enough for our taste, the nose somewhat too rounded, and the lips rather thick, it is impossible to deny that there is great beauty stamped on the countenance. Its profile, when viewed from various points, will probably show some new beauties to those only accustomed to look at it in front. The position of the ear in all Egyptian statues that we have had an opportunity of observing is very peculiar, being always too high; and the ear itself is rather large. We might almost infer, that there was some national peculiarity in this member, from seeing it so invariably placed in the same singular position. The appendage to the chin is common in Egyptian colossal statues, and is undoubtedly intended to mark the beard, the symbol of manhood; and it may be observed not only on numerous statues, but also on painted reliefs, where we frequently see it projecting from the end of the chin and not attached to the breast, but slightly curved upwards. Osiris, one of the great objects of Egyptian adoration, is often thus represented; but the beard is generally only attached to the clothed figure, being, for the most part, but not always, omitted on naked ones. The colossal figures, No. 8 and 38, have both lost their beards. There is a colossal head in the Museum, No. 57, that is peculiar in having the upper margin of the beard represented by incisions on the chin, after the fashion of Greek bearded statues. It is the only instance we have seen, either in reality or in any drawing, of a colossus with a genuine beard. There is more variety in the head-dresses of colossal statues than in their beards. No. 8, opposite the Memnon, has the high cap which occurs very often on Egyptian standing colossi, which are placed with their backs to pilasters. No. 38 has the flat cap fitting close to the head and descending behind, very much like the pigtails once in fashion. The Memnon head-dress differs from both of these, and has given rise to discussions, called learned, into which we cannot enter here. On the forehead of this colossus may be seen the remains of the erect serpent, the emblem of royalty, which always indicates a deity or a royal personage. This erect serpent may be traced on various monuments of the Museum, and perhaps occurs more frequently than any single sculptured object.

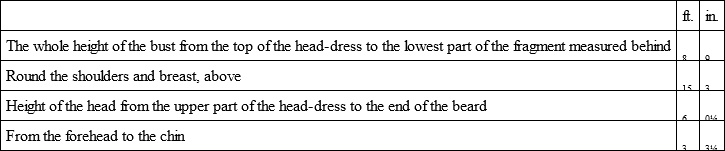

“Our limits prevent us from going into other details, but we have perhaps said enough to induce some of our readers to look more carefully at this curious specimen of Egyptian art; and to examine the rest of the ornamental parts. The following are some of the principal dimensions: —

“Judging from these dimensions, the figure in its entire state would be about twenty-four feet high as seated on its chair: which is about half the height of the real Memnon, who still sits majestic on his ancient throne, and throws his long shadow at sun-rise over the plain of Thebes.”

Many pages have been written in regard to the time when the arch was first invented. It is not known that the two divisions of the city were ever connected by any bridge.

“A people,” remarks Heeren, “whose knowledge of architecture had not attained to the formation of arches, could hardly have constructed a bridge over a river, the breadth of which would even now oppose great obstacles to such an undertaking. We have reason to believe, however, that the Egyptians were acquainted with the formation of the arch, and did employ it on many occasions. Belzoni contends that such was the case, and asserts that there is now at Thebes a genuine specimen, which establishes the truth of his assertion. No question exists, it should be observed, that arches are to be found in Thebes; it is their antiquity alone which has been doubted. The testimony of Mr. Wilkinson on this point is decisive in their favour. He tells us that he had long been persuaded that most of the innumerable vaults and arches to be seen at Thebes, were of an early date, although unfortunately, from their not having the names of any of the kings inscribed on them, he was unable to prove the fact; when, at last, chance threw in his way a tomb vaulted in the usual manner, and with an arched door-way, ‘the whole stuccoed, and bearing on every part of it the fresco paintings and name of Amunoph the First,’ who ascended the throne 1550 years B. C. We thus learn that the arch was in use in Egypt nearly three thousand four hundred years ago, – or more than twelve hundred years before the period usually assigned as the date of its introduction among the Greeks.”

At Thebes have lately been found, that is, about fifteen years ago, several papyri; one of which gives an ancient contract for the sale of land in this city. The following is a translation: —

“‘In the reign of Cleopatra and Ptolemy her son, surnamed Alexander, the gods Philometores Soteres, in the year XII, otherwise IX; in the priesthood, &c. &c., on the 29th of the month Tybi; Apollonius bring president of the Exchange of the Memnonians, and of the lower government of the Pathyritic Nome.

“‘There was sold by Pamonthes, aged about 45, of middle size, dark complexion, and handsome figure, bald, round-faced, and straight-nosed; and by Snachomnenus, aged about 20, of middle size, sallow complexion, likewise round-faced, and straight-nosed; and by Semmuthis Persineï, aged about 22, of middle size, sallow complexion, round-faced, flat-nosed, and of quiet demeanour; and by Tathlyt Persineï, aged about 30, of middle size, sallow complexion, round face, and straight nose, with their principal, Pamonthes, a party in the sale; the four being of the children of Petepsais, of the leather-cutters of the Memnonia; out of the piece of level ground which belongs to them in the southern part of the Memnonia, eight thousand cubits of open field; one-fourth of the whole, bounded on the south by the Royal Street; on the north and east by the land of Pamonthes and Boconsiemis, who is his brother, – and the common land of the city; on the west by the house of Tages, the son of Chalome; a canal running through the middle, leading from the river; these are the neighbours on all sides. It was bought by Nechutes the Less, the son of Asos, aged about 40, of middle size, sallow complexion, cheerful countenance, long face, and straight nose, with a scar upon the middle of his forehead; for 601 pieces of brass; the sellers standing as brokers, and as securities for the validity of the sale. It was accepted by Nechutes the purchaser.

“‘Apollonius, Pr. Exch.’“Attached278 to this deed is a registry, dated according to the day of the month and year in which it was effected, ‘at the table in Hermopolis, at which Dionysius presides over the 20th department;’ and briefly recapitulating the particulars of the sale, as recorded in the account of the partners receiving the duties on sales, of which Heraclius is the subscribing clerk; so that even in the days of the Ptolemies there was a tax on the transfer of landed property, and the produce of it was farmed out in this case to certain ‘partners.’

“According to Champollion, the date of this contract corresponds to the 13th or 14th of February, 105 B. C., and that of the registry to the 6th or the 14th of May in the same year. Dr. Young fixes it in the year 106 B. C.

“The contract is written in Greek; it is usually called the ‘Contract of Ptolemais,’ or the ‘Papyrus of M. d’Anatasy,’ having been first procured by a gentleman of that name, the Swedish consul at Alexandria. Three other deeds of a similar kind, but rather older, and written in the enchorial, or demotic character, were brought from Thebes, about fifteen years ago, by a countryman of our own, Mr. G. F. Grey, the same gentleman who was fortunate enough to bring that Greek papyrus which turned out, by a most marvellous coincidence, to be a copy of an Egyptian manuscript which Dr. Young was at the very time trying to decipher. These three deeds are in the enchorial character, and accompanied with a registry in Greek. They all relate to the transfer of land ‘at the southern end of Diospolis the Great,’ as the Greek registries have it. The Greek papyrus, too, of which we just spoke, and the original Paris manuscript, of which it is a copy, are instruments for the transfer of the rent of certain tombs in the Libyan suburb of Thebes, in the Memnonia; and also of the proceeds arising from the performance of certain ‘liturgies’ on the account of the deceased. They have been invaluable aids in the study of ancient Egyptian literature.”

The emperor Constantine, ambitious of foreign ornaments, resolved to decorate his newly-founded capital of Constantinople with the largest of all the obelisks that stood on the ruins of Thebes. He succeeded in having it conveyed as far as Alexandria, but, dying at the time, its destination was changed; and an enormous raft, managed by three hundred rowers, transported the granite obelisk from Alexandria to Rome.

Among the treasures of antiquity, found in the Thebais, were, till very lately, two granite columns, of precisely the same character as Cleopatra’s Needles. Of these one remains on the spot; the other, with great labour and expense, has been transported to Paris. When the French army, in their attempt on Egypt, penetrated as far as Thebes, they were, almost to a man, overpowered by the majesty of the ancient monuments they saw before them; and Buonaparte is then said to have conceived the idea of removing at least one of the obelisks to Paris. But reverses and defeat followed. The French were compelled to abandon Egypt; and the English, remaining masters of the seas, effectually prevented any such importation into France.

“279Thirty years after Buonaparte’s first conception of the idea, the French government, then under Charles X., having obtained the consent of the pasha of Egypt, determined that one of the obelisks of Luxor should be brought to Paris. ‘The difficulties of doing this,’ says M. Delaborde, ‘were great. In the first place, it was necessary to build a vessel which should be large enough to contain the monument, deep enough to stand the sea, and, at the same time, draw so little water as to be able to ascend and descend such rivers as the Nile and the Seine.’

“In the month of February, 1831, when the crown of France had passed into the hands of Louis Philippe, a vessel, built as nearly as could be on the necessary principles, was finished and equipped at Toulon. This vessel, which for the sake of lightness was chiefly made of fir and other white wood, was named the ‘Luxor.’ The crew consisted of one hundred and twenty seamen, under the command of Lieutenant Verninac, of the French royal navy; and there went, besides, sixteen mechanics of different professions, and a master to direct the works under the superintendence of M. Lebas.

“After staying forty-two days at Alexandria, the expedition sailed for the mouth of the Nile. At Rosetta they remained some days, and on the 20th of June M. Lebas, the engineer, two officers, and a few of the sailors and workmen, leaving the ‘Luxor’ to make her way up the river slowly, embarked in common Nile-boats for Thebes, carrying with them the tools and materials necessary for the removal of the obelisk. The ‘Luxor’ did not arrive at Thebes until the 14th of August, which was two months after her departure from Alexandria.

“Reaumur’s thermometer marked from thirty degrees to thirty-eight in the shade, and ascended to fifty, and even to fifty-five degrees, in the sun. Several of the sailors were seized with dysentery, and the quantity of sand blown about by the wind, and the glaring reflection of the burning sun, afflicted others with painful ophthalmia. The sand was particularly distressing: one day the wind raised it and rolled it onward in such volume as, at intervals, to obscure the light of the sun. After they had felicitated themselves on the fact that the plague was not in the country, they were struck with alarm, on the 29th of August, by learning that the cholera morbus had broken out most violently at Cairo. On the 11th of September the same mysterious disease declared itself on the plain of Thebes, with the natives of which the French were obliged to have frequent communications. In a very short time fifteen of the sailors, according to M. J. U. Angelina, the surgeon, caught the contagion, but every one recovered under his care and skill.

“In the midst of these calamities and dangers, the French sailors persevered in preparing the operations relative to the object of the expedition. One of the first cares of M. Lebas, on his arriving on the plain of Thebes, was to erect near to the obelisks, and not far from the village of Luxor, proper wooden barracks – sheds and tents to lodge the officers, sailors, and workmen on shore; he also built an oven to bake them bread, and magazines in which to secure their provisions, and the sails, cables, &c. of the vessel.

“The now desolate site, on which the City of the Hundred Gates once stood, offered them no resources of civilised life. But French soldiers and sailors are happily, and, we may say, honourably distinguished, by the facility with which they adapt themselves to circumstances, and turn their hands to whatever can add to their comfort and well-being. The sailors on this expedition, during their hours of repose from more severe labours, carefully prepared and dug up pieces of ground for kitchen-gardens. They cultivated bread-melons and watermelons, lettuces, and other vegetables; they even planted some trees, which thrived very well; and, in short, they made their place of temporary residence a little paradise, as compared with the wretched huts and neglected fields of the oppressed natives.

“It was the smaller of the two obelisks the French had to remove; but this smaller column of hard, heavy granite was seventy-two French feet high, and was calculated to weigh upwards of two hundred and forty tons. It stood, moreover, at the distance of about one thousand two hundred feet from the Nile, and the intervening space presented many difficulties.

“M. Lebas commenced by making an inclined plane, extending from the base of the obelisk to the edge of the river. This work occupied nearly all the French sailors, and about seven hundred Arabs, during three months; for they were obliged to cut through two hills of ancient remains and rubbish, to demolish half of the poor villages which lay in their way280, and to beat, equalise, and render firm the uneven, loose, and crumbling soil. This done, the engineer proceeded to make the ship ready for the reception of the obelisk. The vessel had been left aground by the periodical fall of the waters of the Nile, and matters had been so managed that she lay imbedded in the sand, with her figure-head pointing directly towards the temple and the granite column. The engineer, taking care not to touch the keel, sawed off a section of the front of the ship; in short, he cut away her bows, which were raised, and kept suspended above the place they properly occupied, by means of pulleys and some strong spars, which crossed each other above the vessel.

“The ship, thus opened, presented in front a large mouth to receive its cargo, which was to reach the very lip of that mouth or opening, by sliding down the inclined plane. The preparations for bringing the obelisk safely down to the ground lasted from the 11th of July to the 31st of October, when it was laid horizontally on its side.

“The rose-coloured granite of Syene (the material of these remarkable works of ancient art), though exceedingly hard, is rather brittle. By coming into contact with other substances, and by being impelled along the inclined plane, the beautiful hieroglyphics, sculptured on its surface, might have been defaced, and the obelisk might have suffered other injuries. To prevent these, M. Lebas encased it, from its summit to its base, in strong thick wooden sheathings, well secured to the column by means of hoops. The western face of this covering, which was that upon which the obelisk was to slide down the inclined plane, was rendered smooth, and was well rubbed with grease to make it run the easier.

“To move so lofty and narrow an object from its centre of gravity was no difficult task, – but then came the moment of intense anxiety! The whole of the enormous weight bore upon the cable, the cordage, and machinery, which quivered and cracked in all their parts. Their tenacity, however, was equal to the strain, and so ingeniously were the mechanical powers applied, that eight men in the rear of the descending column were sufficient to accelerate or retard its descent.

“On the following day the much less difficult task of getting the obelisk on board the ship was performed. It only occupied an hour and a half to drag the column down the inclined plane, and (through the open mouth in front) into the hold of the vessel. The section of the suspended bows was then lowered to the proper place, and readjusted and secured as firmly as ever by the carpenters and other workmen. So nicely was this important part of the ship sliced off, and then put to again, that the mutilation was scarcely perceptible.

“The obelisk was embarked on the 1st of November, 1831, but it was not until the 18th August 1832, that the annual rise of the Nile afforded sufficient water to float their long-stranded ship. At last, however, to their infinite joy, they were ordered to prepare every thing for the voyage homewards. As soon as this was done, sixty Arabs were engaged to assist in getting them down the river, (a distance of 180 leagues), and the ‘Luxor’ set sail.

“After thirty-six days of painful navigation, but without meeting with any serious accident, they reached Rosetta; and there they were obliged to stop, because the sand bank off that mouth of the Nile had accumulated to such a degree, that, with its present cargo the vessel could not clear it. Fortunately, however, on the 30th of December, a violent hurricane dissipated part of this sand-bank; and, on the first of January, 1833, at ten o’clock in the morning, the ‘Luxor’ shot safely out of the Nile, and at nine o’clock on the following morning came to a secure anchorage in the old harbour of Alexandria.

“Here they awaited the return of the fine season for navigating the Mediterranean; and the Sphynx (a French man-of-war) taking the ‘Luxor’ in tow, they sailed from Alexandria on the 1st of April. On the 2nd, a storm commenced, which kept the ‘Luxor’ in imminent danger for two whole days. On the 6th, the storm abated; but the wind continued contrary, and soon announced a fresh tempest. They had just time to run for shelter into the bay of Marmara, when the storm became more furious than ever.

“On the 13th of April, they again weighed anchor, and shaped their course for Malta; but a violent contrary wind drove them back as far as the Greek island of Milo, where they were detained two days. Sailing, however, on the 17th, they reached Navarino on the 18th, and the port of Corfu, where they were kindly received by Lord Nugent and the British, on the 23d of April. Between Corfu and Cape Spartivento, heavy seas and high winds caused the ‘Luxor’ to labour and strain exceedingly. As soon, however, as they reached the coast of Italy, the sea became calm, and a light breeze carried them forward, at the rate of four knots an hour, to Toulon, where they anchored during the evening on the 11th of May.

“They had now reached the port whence they had departed, but their voyage was not yet finished. There is no carriage by water, or by any other commodious means, for so heavy and cumbrous a mass as an Egyptian obelisk, from Toulon to Paris (a distance of above four hundred and fifty miles). To meet this difficulty they must descend the rest of the Mediterranean, pass nearly the whole of the southern coast of France, and all the south of Spain – sail through the straits of Gibraltar, and traverse part of the Atlantic, as far as the mouth of the Seine, which river affords a communication between the French capital and the ocean.

“Accordingly, on the 22d of June, they sailed from Toulon, the ‘Luxor’ being again taken in tow by the Sphynx man-of-war; and, after experiencing some stormy weather, finally reached Cherbourg on the 5th of August, 1833. The whole distance performed in this voyage was upwards of four hundred leagues.

“As the royal family of France was expected at Cherbourg by the 31st of August, the authorities detained the ‘Luxor’ there. On the 2d of September, King Louis Philippe paid a visit to the vessel, and warmly expressed his satisfaction to the officers and crew. He was the first to inform M. Verninac, the commander, that he was promoted to the rank of captain of a sloop-of-war. On the following day, the king distributed decorations of the Legion of Honour to the officers, and entertained them at dinner.

“The ‘Luxor,’ again towed by the Sphynx, left Cherbourg on the 12th of September, and safely reached Havre de Grace, at the mouth of the Seine. Here her old companion, the Sphynx, which drew too much water to be able to ascend the river, left her, and she was taken in tow by the Neva steam-boat. To conclude with the words of our author: ‘At six o’clock (on the 13th) our vessel left the sea for ever, and entered the Seine. By noon we had cleared all the banks and impediments of the lower part of the river; and on the 14th of September at noon, we arrived at Rouen, where the ‘Luxor’ was made fast before the quay d’Harcourt. Here we must remain until the autumnal rains raise the waters of the Seine, and permit us to transport to Paris this pyramid, – the object of our expedition.’ This event has since happened, and the recent French papers announce that the obelisk has been set up in the centre of the Place Louis XVI.”

For a more detailed account of this wonderful city, we must refer to the learned and elaborate account, published a few years since, by Mr. Wilkinson. We now have space only for impressions.

“That ancient city, celebrated by the first of poets and historians that are now extant: ‘that venerable city,’ as Pococke so plaintively expresses it, ‘the date of whose ruin is older than the foundation of most other cities,’ offers, at this day, a picture of desolation and fallen splendour, more complete than can be found elsewhere; and yet ‘such vast and surprising remains,’ to continue in the words of the same old traveller, ‘are still to be seen, of such magnificence and solidity, as may convince any one that beholds them, that without some extraordinary accident, they must have lasted for ever, which seems to have been the intention of the founders of them.’”