полная версия

полная версияOld Country Life

The account-book of Mrs. Joyce Jefferies, a lady resident in Herefordshire and Worcestershire during the Civil War, comprises the receipt and expenditure of nine years. She lived a single person in her house in Hereford, and by no means on a contracted scale. Many female servants are mentioned, two having wages from £3 to £3 4s. per annum, with gowns of dark stuff at midsummer. Her coachman, receiving 40s. per annum, had at Whitsuntide, 1639, a new cloth suit and cloak; and when he was dressed in his best, wore fine blue silk ribbon at the knees of his hose. The liveries of this and another man-servant were, in 1641, of green Spanish cloth, and cost upwards of nine pounds. Her steward received a salary of £5 16s., and she kept for him a horse, which he rode to collect her rents and dues, and to see to the management of her estate.

I have myself a book of accounts, a little later, where the "mayde of my wyfe" gets £3, and the footman £4 and his livery.

In some houses a whole series of account-books has been preserved, showing, among other things, the rise in wages paid for servants, and very instructive they are.

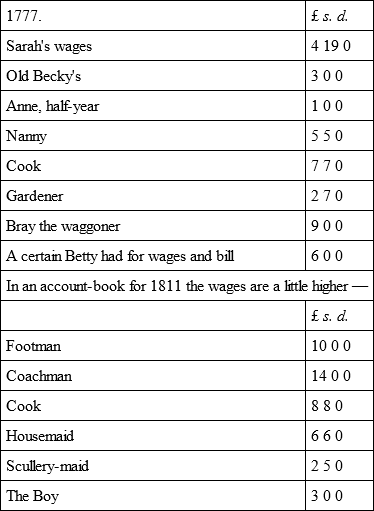

Here is from an account-book of 1777, in a country squire's house. Wages were paid on Lady Day for the whole year, and not quarterly.

There died only a year ago an old woman who had been a servant since she was eighteen in two of the greatest houses in the neighbourhood. When she first went into service, she told me, it was at K – . She received £4 as her wage, and managed to save money on that. She was, however, given a washing-dress by her mistress at Lady Day. After some years she went to L – Park, where she received £6. This was after a while raised to £7, and she invariably put away some of her wage. When after tried service her wage was raised to £10, the climax of her ambition was reached, she regarded herself as passing rich, and never hoped to obtain more.

"For certain, sir," she said, "my work wasn't worth more."

In my own parish churchyard, one of the best of the monuments is that raised by my grandfather to the memory of an old servant of his grandmother's.

MR. THOMAS HILSDEN,

WHO DIED FEB. 21, 1806,AGED 70,HAVING LIVED IN THE FAMILY OFMrs. Margaret Gould, of Lew House,44 YEARSTHIS STONE WAS ERECTEDIN CONSIDERATION OF HIS FAITHFUL SERVICEThere is an ancient family I know of historic dignity. It has lost its ancestral estates, lost almost all of its family portraits; but one great picture remains to it, so poorly painted, that at the sale of the Manor-house and its contents no one would buy it, – it is the portrait of an old servant, a giant, a tall and powerful ranger, who, partly for his size, chiefly for his fidelity, was painted and hung up in the hall along with the knights and squires and ladies of the family which he had served so well.

The mention of this picture leads me to say a few words about a worthy man who died some twenty years ago. Rawle was hind to the late Sir Thomas Acland of Killerton. Sir Thomas introduced Arab blood among the Exmoor ponies, and greatly improved the breed. About 1810 he appointed Rawle in charge of these ponies. He was a fine man, fully six feet high, and big in proportion. His power of breaking in the ponies was extraordinary. He was quite indifferent to falls, often pony and man rolling over and over each other. The sale of the ponies generally took place at Bampton and at Taunton fairs. The system was this – a herd of the wild little creatures was driven into the fair. Buyers attended from all parts of the country, and when a dealer took a fancy to a pony, he pointed him out to the moor-man in attendance, who went into the herd, seized upon the selected one, and brought him out by sheer strength. This is no easy matter, for the Exmoor pony fights with his fore-feet in desperate fashion. It usually took, and takes, two men to do this, but Rawle did not require assistance, such was his strength. Indeed so strong was Rawle, that he would put a hand under the feet of a maid-servant on each side of him, and raise himself and at the same time both of them, till he was upright, and he held each woman on the palm of his hand, one on each side of him, level with his waist. Sir Thomas Acland was wont, when he had friends with him, to get the man to make this exhibition of his strength before them.

Sir Thomas had a hunting box at Higher Combe (called in the district Yarcombe); he occupied one portion of the house when there, a farmer occupied the rest. It was a curious scene – a remnant of feudal times – when Sir Thomas came there. His tenants, summoned for the purpose, had accompanied him in a cavalcade from Winsford, or Hornicott. John Rawle could never be persuaded to eat a bite or take a draught when his master was in a house; he planted himself as a sentry upright before the door when Sir Thomas went in to refresh himself anywhere, and nothing could withdraw him from his post.

In connexion with these expeditions to Higher Combe, it may be added that the cavalcade of tenants would attend Sir Thomas to the wood where a stag had been harboured. Among them was a band, each member of the band played one note only; but it was so arranged that a hunting tune was formed by these notes being played in succession. When the stag was unharboured, and started across the moor, the band commenced this tune, and until it was played out the hounds were kept in leash. The time occupied by this tune was the "law" given to the stag, and when it was ended the hounds were laid on.

A famous china bowl was made in China, and presented to Sir Thomas by the Hunt. This bowl used to be kept at Higher Combe; it represented a stag-hunt. And twelve glasses were presented to Sir Thomas along with it, each engraved with a stag, and the words, "Success to the hunting."

One day Sir Thomas said to Rawle, "Rawle, I want to send a gelding and a mare in foal to Duke Ludwig of Baden, at Baden Baden. Can you take them?"

"Certainly, Sir Thomas."

The man could neither read nor write, and of course knew no other language than the broadest Exmoor dialect – and this was at the beginning of the century, when there were not the facilities for travelling that there are now. He started for Baden Baden, and took his charges there in safety, and delivered them over to the Grand Duke. He had, however, an added difficulty, in that the mare foaled en route, and he had a pass for two ponies only.

Is the old "good and faithful servant" a thing of the past? Not perhaps the good servant, but the servant who continues in a family through the greatest portion of his or her life, who becomes a part of the family, is probably gone for ever; the change in the signification of words tells us of social changes. A man's family, even in Addison's time, comprised his servants. "Of what does your family consist?" A hundred and fifty years ago this would have been answered by an enumeration of those comprising the household, from the children to the scullion. Now who would even think of a servant when such a question is asked? The family is shrunk to the blood-relatives, and the servants are outside the family circle.

We are in a condition of transformation in our relations to our servants; we no longer dream of making them our friends, and consequently they no longer regard us with devotion. But I am not sure that the fault lies with the master. The spirit of unrest is in the land; the uneducated and the partially educated crave for excitement, and find it in change; they can no longer content themselves with remaining in one situation, and when the servants shift quarters every year or two, how can master and mistress feel affection for them, or take interest in them?

Does the reader know Swift's Rules and Directions for Servants? They occupy one hundred and eighteen pages of volume twelve of his works, in the edition of 1768, and comprise instructions to butler, cook, footman, coachman, groom, steward, chambermaid, housemaid, nurse, etc. They show us that human nature among servants was much the same in the middle of last century as in this. Only a scanty extract must be given.

"When your master or lady calls a servant by name, if that servant be not in the way, none of you are to answer, for then there will be no end of your drudgery.

"When you have done a fault be always pert and insolent, and behave yourself as if you were the injured person.

"The cook, the butler, the groom, and every other servant should act as if his master's whole estate ought to be applied to that particular servant's business.

"Take all tradesmen's parts against your master. You are to consider if your master hath paid too much, he can better afford the loss than a poor tradesman.

"Never submit to stir a finger in any business but that for which you were particularly hired. For example, if the groom be drunk or absent, and the butler be ordered to shut the stable-door, the answer is ready, 'An' please, your honour, I don't understand horses.'

"If you find yourself to grow into favour with your master or lady, take some opportunity to give them warning, and when they ask the reason, and seem loath to part with you, answer that a poor servant is not to be blamed if he strives to better himself. Upon which, if your master hath any generosity, he will add five or ten shillings a quarter rather than let you go.

"Write your own name and your sweetheart's with the smoke of a candle on the roof of the kitchen, to show your learning. If you are a young sightly fellow, whenever you whisper your mistress at the table, run your nose full into her cheek, or breathe full in her face.

"Never come till you have been called three or four times, for none but dogs will come at the first whistle.

"When you have broken all your earthen vessels below stairs – which is usually done in a week – the copper-pot will do as well; it can boil milk, heat porridge, hold small beer – apply it indifferently to all these uses, but never wash or scour it.

"Although you are allowed knives for the servants' hall at meals, yet you ought to spare them, and make use of your master's.

"Let it be a constant rule, that no chair or table in the servants' hall have above three legs.

"Quarrel with each other as much as you please, only always bear in mind that you have a common enemy, which is your master and lady.

"When your master and lady go abroad together to dine, you need leave only one servant in the house to answer the door and attend the children. Who is to stay at home is to be determined by short and long cuts, and the stayer at home may be comforted by a visit from a sweetheart.

"When your master or lady comes home, and wants a servant who happens to be abroad, your answer must be, that he had but just that minute stepped out, being sent for by a cousin who was dying. When you are chidden for a fault, as you go out of the room mutter loud enough to be plainly heard.

"When your lady sends for you to her chamber to give you orders, be sure to stand at the door and keep it open, fiddling with the lock all the while she is talking to you.

"When you want proper instruments for any work you are about, use all expedients you can invent. For instance, if the poker be out of the way, stir the fire with the tongs; if the tongs be not at hand, use the muzzle of the bellows, the wrong end of the shovel, or the handle of the fire-brush. If you want paper to singe a fowl, tear the first book you see about the house. Wipe your shoes, for want of a clout, on the bottom of a curtain or a damask napkin.

"There are several ways of putting out a candle, and you ought to be instructed in them all: you may run the candle-end against the wainscot, which puts the snuff out immediately; you may lay it on the ground and tread the snuff out with your foot; you may hold it upside down until it is choked in its own grease, or cram it into the socket of the candlestick; you may whirl it round in your hand till it goes out.

"Clean your plate, wipe your knives, and rub the dirty tables with the napkins and tablecloths used that day, for it is but one washing.

"When a butler cleans the plate, leave the whiting plainly to be seen in all the chinks, for fear your lady should not believe you had cleaned it.

"You need not wipe your knife to cut bread for the table, because in cutting a slice or two it will wipe itself.

"A butler must always put his finger into every bottle to feel whether it be full.

"Whet the backs of your knives until they are as sharp as the edge, that when gentlemen find them blunt on one side they may try the other.

"Cooks should scrape the bottom of pots and kettles with a silver spoon, for fear of giving them a taste of copper.

"Get three or four charwomen to attend you constantly in the kitchen, whom you pay with the broken meat, a few coals, and all the cinders.

"Never make use of a spoon in anything that you can do with your hands, for fear of wearing out your master's plate.

"In roasting and boiling use none but the large coals, and save the small ones for the fires above stairs." And so on.

If the old servants had their merits, they had also their demerits. Have they not bequeathed the latter to their successors, and carried away their merits with them into a better world?

CHAPTER XIII

THE HUNT

THE genuine Englishman loves a hunt, loves sport, above everything else; I do not mean only those who can afford to ride and shoot, but every Englishman born and bred in the country.

One day the masons were engaged on my house, on the top of a scaffold, the carpenters were occupied within laying a floor, some painters were employed on doors and windows, the gardener was putting into a bed some roses; in the back-yard a youth was chopping up wood; in the stable-yard the coachman was washing the body of the carriage, and in the stable itself the groom was currycombing a horse. Suddenly from the hillside opposite, mantled with oak, came the sound of the hounds in cry, and then the call of the horn. Down from the scaffold came the masons, head over heels, at the risk of their necks; out through the windows shot the carpenters and painters, throwing aside hammers, nails, paint-pot and brushes; down went the roses in the garden; from behind the house leaped the wood-chopper; the coach was left half-washed, and the horse half-currycombed; and over the lawn and through the grounds, regardless of everything, went a wild excited throng of masons, carpenters, woodcutter, coachman, stable-boy, gardener, my own sons, then my own self, having dropped pen, and, forgotten on the terrace was left only the baby – a male, erect in its perambulator, with arms extended, screaming to follow the rout and go after the hounds. Let agitators come and storm and denounce in the midst of our people; they cannot rouse them to fury against the gentry, because they and the gentry run after the hounds together, enjoy a hunt together, and are the best of friends in the field. No, the great socialistic revolution will not take place till the hunt is abolished. That is the great solvent of all prejudices, that the great festival that binds all in one common bond of sympathy.

This season there has appeared at our meets an old man of seventy-five, who was for many years a butler to a rector, a quiet, studious man, who died a few years ago. After the death of his master the butler retired on his savings, and built himself a house. Then – this winter he appeared on a cob at the meet of the foxhounds. "Sir," said he to the Master, "now the ambition of my life is satisfied. Since I was a boy I have wished, and all my days have worked, that I might have a cob on which I could hunt."

Alas! the old fellow found himself so stiff after the first hunt, that at the next meet of the harriers he appeared on foot. He had walked four miles to it; and he ran with the hounds, and was in at the death. After the hunt he walked home hot and happy, and elastic in step.

The farmers naturally like a hunt, as it affords them, apart from the sport, an occasion of showing off and selling their horses. The workmen like a hunt, especially after the hare, for it forms a break in their work. They have their half day's sport, and their masters pay wage just the same as if they had been at work.

The hare hunt naturally lends itself to footers, as the hare runs in a circle, and not straight with the wind in his tail like reynard. Here and there is to be found a cantankerous farmer who objects to having his hedges broken down and his land trampled by the hunters, but he is looked on with distrust and dislike by all in every class, and spoken of as a curmudgeon. Of course, also, there are to be found men who trap and kill foxes, but I verily believe those men's consciences sting them far more on this account than if they had committed a fraud or become drunk. And – by the way, that reminds me of a story.

There came a Hungarian nobleman, whom we will call the Baron Hounymhum, to England. His Christian name was Arpad. He came to England, having a title, but having nothing else; he came, in fact, to seek there his fortune. Belonging to a good family, he was well supplied with letters of introduction, and he was received into society. On more than one occasion he donned his uniform, and had reason to believe that the uniform as well as his handsome face was much admired by the ladies, and envied by the men. Among the acquaintances he made was the Hon. Cecil Blank, through whom he was introduced to one of the first clubs in Piccadilly. He also got acquainted with Lord Ashwater. This nobleman was fond of collecting around him notabilities of all kinds, literary, scientific, and political. He himself was in his politics an advanced Liberal.

The Baron Arpad found, to his astonishment, soon after his arrival in town, that a rumour had got about that he had been implicated in an attempt to assassinate his most gracious sovereign Franz Joseph, King of Hungary and Bohemia, and Emperor of Austria. The idea was absolutely baseless. The fact that he was received at the embassy ought to have shut men's mouths, but no – he was credited with having contrived an infernal machine for the destruction of his beloved sovereign.

He found, to his amazement, that this rumour did him good. He became an interesting foreigner; hitherto he had been only a foreigner. Quite an eager feeling manifested itself among persons of rank and position for having him at their parties; not only so, but he was solicited by magazine editors to write for them articles on the Anarchist party in Hungary and Austria.

Scarce had this odious rumour died away, before he became the victim of another, equally false and equally detestable. A distant cousin, the Baron Adorian Hounymhum, ran away with the Princess Nornenstein, the mother of three sweet little children. The elopement caused a great sensation at Vienna, as the princess was much esteemed by her Majesty the Empress. Prince Nornenstein pursued the fugitives, overtook them in Belgium, fought a duel with the baron, and was shot through the heart.

Well, the report got about that it was Baron Arpad who had run away with the princess, ruined her home, deprived her sweet children of father and mother, and shot the aggrieved husband. It was in vain for him to protest, he was credited with these infamies – and rose in popular estimation. The Duchess of Belgravia at once invited him to her dances. The ladies now courted his society, as before the gentlemen had courted it, when they held him to be a would-be regicide. These two rumours, crediting him with crimes of which he was incapable, did a great deal towards pushing him in society.

Among the many acquaintances the Baron made in town was Mr. Wildbrough, a country squire, M.F.H., a man of wealth, and an M.P. for his county. He had but one daughter, who would be his heiress, and who did not seem insensible to the good looks of the Baron. Now, thought the Hungarian, his opportunity had arrived. The position of landed proprietor in England was in prospect. Moreover, Mr. Wildbrough had invited the Baron to come to Wildbrough Hall in October to see the first meet of the foxhounds.

At the time appointed the Baron arrived, and was cordially received by the squire; Mrs. Wildbrough was gracious, but not gushing; Mary Wildbrough was manifestly pleased to see him – the tell-tale blood assured him of that.

A large party was assembled at the hall for the first meet of the season. The masters of other packs in the county were present. The meet was picturesque, the run excellent. The Baron was in at the death, and received the brush, which he at once presented to Mary Wildbrough. He had ridden beside her, and he felt that his prospects were brightening. He proposed to make the offer that evening at the dance after dinner, when, at Mary's particular request, he was to appear in his Magyar Hussar uniform, in which, as he well knew, he would be irresistible. The Baron took in Mary to dinner, and had an agreeable chat with her, which was only interrupted by Sir Harry Treadwin, a sporting baronet, who said across the table to him, "Baron, I suppose that you have foxes in Hungary?"

"Oh, yes," answered he, "I have shot as many as five or six in a day."

The Baron spoke loud, so as to be heard by all. He was quite unprepared for the consequences. Sir Harry stared at him as at a ghost, with eyes and nostrils and mouth distended. A dead silence fell on the whole company. The host's red face changed colour, and became as collared brawn. The master of another pack became purple as a plum. Mrs. Wildbrough fanned herself vigorously. Mary became white as a lily and trembled, whilst tears welled up in her beautiful eyes. The lady of the house bowed to the lady whom the squire had taken in, and in silence all rose, and the ladies without a word left the room.

The gentlemen remained; conversation slowly unthawed. The Baron turned to the gentleman nearest him, and spoke about matters of general interest. He answered shortly, almost rudely, and turned to converse with his neighbour on the other side. Then the Baron addressed Sir Harry, but he seemed deaf, he stared icily, but made no reply. It was a relief to an intolerable restraint when the gentlemen joined the ladies.

The Baron knew that with his handsome face and gorgeous uniform he could command as many partners in the dance as he desired; but what was his chagrin to find that his anticipations were disappointed. One young lady was engaged, another did not dance the mazurka, a third had forgotten the lancers, a fourth was tired, and a fifth indisposed. After a while he seized his chance, and caught Mary Wildbrough in the conservatory, – she was crying.

"Miss Wildbrough," said he, "are you ill? What ails you?"

"Oh, Baron!" Then she burst into an uncontrollable flood of tears. "I am so – so unhappy! Five or six foxes! Oh, Baron Hounymhum!"

Next day he left. His host would not shake hands with him when he departed. On reaching town he felt dull, and sauntered to the club, but no one would speak to him there. Next day he received this letter from the secretary —

"The secretary of the – Club regrets to be obliged to inform the Baron Hounymhum that he can no longer be considered the guest of the Club."

After that London society was sealed to him. It was nothing that he had been thought guilty of an attempt to assassinate his sovereign, nothing that he was thought to have eloped with a married woman, wrecked her home and shot her husband, but that he should have shot foxes was The Unpardonable Sin.

We have a peculiar institution in the county of Devon – a week of hare-hunting on Dartmoor after hare-hunting has ceased everywhere else. Dartmoor is a high elevated region totally treeless, with peaks covered with granite, having brawling streams that foam down the valleys between. One main road crosses this vast desolate region, as far as Two Bridges, where is an inn, The Saracen's Head, and there it divides, and runs for many miles more over moor to Moreton Hampstead on one side, and to Ashburton on the other. In the fork of this Y stands an eminently picturesque rugged tor, crested by and strewn with granite, called Bellever. About Easter – anyhow, after hare-hunting has ceased elsewhere – the country-side gathers at Bellever for a week, and nothing can be conceived more changed than the scene at this time from the usual solitude and stillness. The tor is covered with horses, traps, carriages, footers; and if the spring sun be shining, nothing can well be more picturesque.