полная версия

полная версияThrough Finland in Carts

"I found the Hotel was so full when I came that I told the landlord rooms would be required to-night, for I did not wish you to be disappointed."

She was a stranger, and her thoughtfulness was very kind. The plot thickened, however, a moment afterwards, when the Russian General, who had also travelled for a whole day on a steamer with us, arrived in his scarlet-lined uniform, and, saluting profoundly, begged to inform Madame he had taken the liberty of bespeaking rooms "as the Hotel was very full."

This was somewhat alarming, and it actually turned out that three suites of rooms had been engaged for us by three different people, each out of the goodness of his heart trying to avoid the dreadful possibility of our being sent away roofless. No wonder our host, thinking such a number of Englishwomen were arriving, had procured the only carriage in the neighbourhood and ordered it and a cart to come down to the pier and await this vast influx of folk. Although the Hotel was not a hundred yards actually from where we stood, everybody insisted on our getting into the little carriage for the honour of the thing, and my sister and I drove off in triumph by a somewhat circuitous route to the Hotel, only to find all our friends and acquaintances there before us, as they had come up the short way by the steps.

Even more strange was the fact that each one of our kind friends had told a certain Judge and his wife of our probable arrival, and promised to introduce the strange English women to them, while, funnily enough, we ourselves bore an introduction from the lady's brother, so, before any of our compagnons de voyage had time to introduce us, we had already made the acquaintance of the Judge and his wife through that gentleman's card. They were all exceedingly kind to us, and we thoroughly enjoyed our short stay among them. Such friendliness is very marked in Finland.

Punkaharju is certainly a strange freak of Nature. Imagine a series of the most queerly-shaped islands all joined together by a natural roadway, for, strange to say, there is a ridge of land sometimes absolutely only the width of the road joining these islands in a connective chain. For about five miles these four or five islands are bound together in this very mysterious manner, so mysterious, in fact, that it seems impossible, as one walks along the roadway, to believe it is nature's freak and not man's hand that has made this extraordinary thoroughfare. It is most beautiful in the wider parts, where, there being more land, the traveller comes upon lovely dells, while the most marvellous mosses and ferns lie under the pine trees, and the flowers are beautiful.

No wonder Runeberg the poet loved to linger here – a veritable enchanted spot.

The morning after our arrival we had a delightful expedition in a boat to the end of the islands; but as a sudden storm got up, in the way that storms sometimes do in Finland, we experienced great difficulty in landing, and were ultimately carried from the boat to the beach in somewhat undignified fashion. However, we landed somehow, and most of us escaped without even wet feet. Just above us was a woodman's house, where our kind Judge had ordered coffee to be in readiness, and thither we started, a little cold and somewhat wet from the waves that had entered our bark and sprinkled us. On the way we paused to eat wild strawberries and to look at the ancient Russian bakeries buried in the earth. These primitive ovens of stone are of great size, for a whole regiment had been stationed here at the time of the war early in the last century when Russia conquered Finland. And then we all sat on the balcony of the woodman's cottage and enjoyed our coffee, poured from a dear little copper pot, together with the black bread and excellent butter, which were served with it.

On that balcony some six or eight languages were spoken by our Finnish friends, such wonderful linguists are they as a nation. At the end of our meal the wind subsided and out came the most brilliant sunshine, changing the whole scene from storm to calm, like a fairy transformation at the pantomime.

We walked back to the Hotel, and the Finlanders proved to be right. As a beautiful bit of quaint nature, Punkaharju equals some of the finest passes in Scotland, while its formation is really most remarkable.

A ridiculous incident happened that day at dinner. Grandpapa, like a great many other persons in Finland, being a vegetarian, had gone to the rubicund and comfortable landlord that morning and explained that he wanted vegetables and fruit for his dinner. At four o'clock, the time for our mid-day meal, we all seated ourselves at table with excellent appetites, the Judge being on my left hand and his wife on my right.

We had all fetched our trifles from the Smörgåsbord, and there ensued a pause before the arrival of the soup. Solemnly a servant, bearing a large dish, came up to our table, and in front of our youthful Grandpapa deposited her burden. His title naturally gave him precedence of us all – an honour his years scarcely warranted. The dish was covered with a white serviette, and when he lifted the cloth, lo! some two dozen eggs were lying within its folds.

"How extraordinary," he said; "I told the landlord I was a vegetarian, and should like some suitable food; surely he does not think I am going to eat this tremendous supply of eggs."

We laughed.

"Where is our dinner?" we asked, a question which interested us much more than his too liberal supply.

"Oh! it will come in a moment," he replied cheerfully.

"But did you order it?" we ventured to inquire.

"No, I cannot say I did. There is a table d'hôte."

Unmercifully we chaffed him. Fancy his daring to order his own dinner, and never inquiring whether we were to have anything to eat or not; he, who had catered for our wants in the mysteries of that castle home, so basely to desert us now.

He really looked quite distressed.

"I'm extremely sorry," he said, "but I thought, being in a hotel, you were sure to have everything you wanted. Of course there is a table d'hôte meal."

At this juncture the servant returned, bearing another large dish. Our dinner, of course, we hoped. Not a bit of it. A large white china basin, full of slices of cucumber, cut, about a quarter of an inch thick, as cucumber is generally served in Finnish houses, again solemnly paused in front of Grandpapa. He looked a little uneasy as he inquired for our dinner.

"This is for the gentleman," she solemnly remarked; and so dish number two, containing at least three entire cucumbers for the vegetarian's dinner, was left before him. Another pause, and still our soup did not come; but the girl returned, this time bearing a glass dish on a long spiral stand filled with red stewed fruit, which, with all solemnity, she deposited in front of Grandpapa.

His countenance fell. Twenty-four eggs, three cucumbers, and about three quarts of stewed fruit, besides an enormous jug of milk and an entire loaf of bread, surrounded his plate, while we hungry mortals were waiting for even crumbs.

Fact was, the good housewife, unaccustomed to vegetarians, could not rightly gauge their appetites, and as the gentleman had ordered his own dinner she thought, and rightly, he was somebody very great, and accordingly gave him the best of what she had, and that in large quantities.

After dinner, which, let us own, was excellent, we had to leave our kind friends and drive back in the soft light of the night to Nyslott, for which purpose we had ordered two kärra (Swedish for cart), karryts (Finnish name), a proceeding which filled the Judge and his wife with horror.

"It is impossible," they said, "that you can drive such a distance in one of our ordinary Finnish kärra. You do not know what you are undertaking. You will be shaken to death. Do wait and return to-morrow by the steamer."

We laughed at their fears, for had we not made up our minds to travel a couple of hundred miles through Finland at a not much later date by means of these very kärra? Certainly, however, when we reached the door our hearts failed us a little.

The most primitive of market carts in England could not approach the discomfort of this strange Finnish conveyance. There were two wheels, undoubtedly, placed across which a sort of rough-and-ready box formed the cart; on this a seat without a back was "reserved" for us. The body of the kärra was strewn with hay, and behind us and below us, and before us our luggage was stacked, a small boy of twelve sitting on our feet with his legs dangling out at the side while he drove the little vehicle.

Grandpapa and I got into one, our student friend and my sister into the other, and away we went amid the kindly farewells of all the occupants of the hostelry, who seemed to think we were little short of mad to undertake a long tiring journey in native carts, and to elect to sleep at our haunted castle on an island, instead of in a proper hotel.

We survived our drive – nay more, we enjoyed it thoroughly, although so shaken we feared to lose every tooth in our heads. It was a lovely evening, and we munched wild strawberries by the way, which we bought for twopence in a birch-bark basket from a shoeless little urchin on the road. We had no spoon of course; but we had been long enough in Finland to know the correct way to eat wild strawberries was with a pin. The pin reminds us of pricks, and pricks somehow remind of soap, and soap reminds us of a little incident which may here be mentioned.

An old traveller never leaves home without a supply of soap; so, naturally, being very old travellers, we started with many cakes among our treasured possessions. But in the interior of Suomi, quite suddenly, one of our travelling companions confided to us the fact that he had finished his soap, and could not get another piece. My sister's heart melted, and she gave away our last bit but one, our soap having likewise taken unto itself wings. He was overjoyed, for English soap is a much-appreciated luxury in all foreign lands. Some days went by and the solitary piece we had preserved grew beautifully less and less; but we hoped to get some more at each little village we came to. We did not like to confide our want to our friend, lest he should feel that he had deprived us of a luxury – we might say a necessity.

Every morning my sister grumbled that our soap was getting smaller and smaller, which indeed it was, while the chance of replacing it grew more and more remote. Her grief was so real, her distress so great, that I could not help laughing at her discomfiture, and, whenever possible, informed her that I was about to wash my hands for the sake of enjoying the last lather of our rapidly dwindling treasure. At last she became desperate.

"I don't care what it costs," she said; "I don't care how long it takes, but I am going out to get a piece of soap, if I die for it."

So out she went, and verily she was gone for hours. I began to think she had either "died for it," or got into difficulties with the language, or been locked up in a Finnish prison!

I was sitting writing my notes, when suddenly the door was thrown open, and my sister, her face aflame with heat and excitement, appeared with a large bright orange parcel under her arm.

"I've got it, I've got it," she exclaimed.

"Got what – the measles or scarlet fever?"

"Soap," she replied with a tragic air, waving the bright orange bag over her head.

"You don't mean to say that enormous parcel contains soap?"

"I do," she replied. "I never intend to be without soap again, and so I bought all I could get. At least," with a merry twinkle and in an undertone, she added, "I brought away as little as I could, after explaining to the man for half an hour I did not want the enormous quantity he wished to press upon me."

Dear readers, it was not beautiful pink scented soap, it was not made in Paris or London; heaven only knows the place of its birth; it gave forth no delicious perfume; it was neither green, nor yellow, nor pink, to look upon. It was a hideous brown brick made in Lapland, I should think, and so hard it had probably been frozen at the North Pole itself.

But that was not all; when we began to wash, this wondrous soap which had cost so much trouble to procure – such hours in its pursuit – was evidently some preparation for scrubbing floors and rough household utensils, for there was a sandy grit about it which made us clean, certainly, but only at the expense of parting with our skin.

My poor sister! Her comedy ended in tragedy.

CHAPTER XIII

THE LIFE OF A TREE

What different things are prized in different lands!

When walking round a beautiful park on an island in Suomi, the whole of which and a lovely mansion belonged to our host, he pointed with great pride to three oak trees, and said —

"Look at our oaks, are they not wonderful?"

We almost smiled. They were oaks, certainly, perhaps as big in circumference as a soup plate, which to an English mind was nothing; but the oak, called in Finnish Jumalan Puu, or God's tree, is a great rarity in Suomi, and much prized, whereas the splendid silver birches and glorious pines, which call forth such praise and admiration from strangers, count for nothing, in spite of the magnificent luxuriance of their growth.

The pine is one of the most majestic of all trees. It is so superbly stately – so unbending to the breeze. It raises its royal head aloft – soaring heavenwards, heedless of all around; while the silvery floating clouds gently kiss its lofty boughs, as they fleet rapidly hither and thither in their endless chase round this world. Deep and dark are the leaves, strong and unresisting; but even they have their tender points, and the young shoots are deliciously green and sweet scented. Look at its solid stem – so straight that every maiden passing by sighs as she attempts to imitate its superb carriage, and those very stems are coloured by a wondrous pinky hue oft-times; so pink, in fact, we pause to wonder if it be painted by Nature's brush, or is merely a whim of sunset playing upon the sturdy bark.

Look beneath the pine; its dark and solid grandeur protects and fosters the tenderest of green carpets. See the moss of palest green, its long fronds appearing like ferns, or note those real ferns and coarser bracken fighting the brambles for supremacy or trying to flout that little wild rose daring to assert its individuality.

Pines and silver birches flourish on all sides.

Everything or anything can apparently be made of birch bark in Finland – shoes, baskets, huge or small, salt bottles, flower vases – even an entire suit of clothing is hanging up in Helsingfors Museum, manufactured from the bark of the silver birch.

The bark thus used, however, is often cut from the growing tree, but this requires to be carefully done so as not to destroy the sap. As one drives through the forests, one notices that many of the trees have dark-brown rings a foot or more wide round their trunks, showing where the bark has been stripped away. The ribband for plaiting is made, as a rule, about an inch wide, although narrower necessarily for fine work, and then it is plaited in and out, each article being made double, so that the shiny silvery surface may show on either side. Even baby children manipulate the birch bark, and one may pass a cluster of such small fry by the roadside, shoeless and stockingless, all busily plaiting baskets with their nimble little fingers. We often marvelled at their dexterity.

What were those packets of brown paper securely fixed to the top of long poles all over that field, we wondered?

"Why, sheets of birch bark," answered our friend, "put out to dry in the sun for the peasants to plait baskets and boxes, shoes and satchels, such as you have just seen; they peeled those trees before cutting them down."

On another of our drives we noticed bunches of dried leaves tied at the top of some of the wooden poles which support the strangely tumbledown looking wooden fences which are found everywhere in Finland, and serve not only as boundaries to fields but also to keep up the snow.

"What are those dead leaves?" we asked the lad who drove our kärra.

"They are there to dry in the sun, for the sheep to eat in the winter," was his reply, with which we ought to have rested satisfied; but thinking that was not quite correct, as they were in patches round some fields and not in others, we asked the boy of the second springless vehicle the same question.

"Those," he said, "are put up to dry in the sun round the rye fields, and in the autumn, when the first frost comes and might destroy the whole crop in a single night, they are lighted, and the warmth and the wind from them protect the crops till they can be hastily gathered the next day."

This sounded much more probable, and subsequently proved perfectly correct. These sudden autumn frosts are the farmer's terror, for his crops being left out one day too long may mean ruin, and that he will have to mix birch bark or Iceland moss with his winter's bread to eke it out, poor soul!

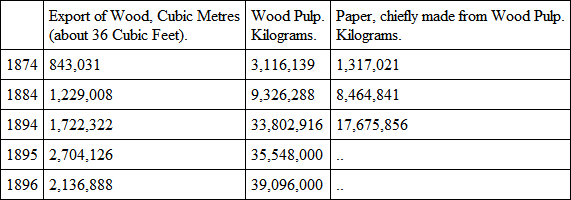

The export of timber from Finland is really its chief trade.

In 1909, 5,073,513 cubic metres of wood were exported, and 192,373,500 kilograms of pulp and paper.

From this table it will be seen that a large quantity of pulp is exported, likewise a great deal of paper, and chiefly to our own country.

England exports to Finland somewhat, but very little, of her own produce, unfortunately; tea, coffee, sugar, and such foreign wares being transhipped from England and Germany – principally from the latter to Finland. The foreign inland trade of Suomi is chiefly in the hands of the Germans. "Made in Germany" is as often found on articles of commerce, as it is in England. Well done, Germany!

We gained some idea of the magnitude of the Finnish wood trade when passing Kotka, a town in the Gulf of Finland, lying between Helsingfors and Wiborg.

Immense stacks of sawn wood were piled up at Kotka, and in the bay lay at least a dozen large ships and steamers, with barges lying on either side filling them with freight as quickly as possible for export to other lands.

The trees of Finland are Finland. They are the gold mines of the country, the props of the people, the products of the earth; the money bags that feed most of its two million and a half of inhabitants. The life of a Finnish tree is worth retailing from the day of its birth until it forms the floor or walls of a prince's palace or a peasant's hut. To say that Finland is one huge forest is not true, for the lakes – of which there are five or six thousand – play an important part, and cover about one-sixth of the country, but these lakes, rivers, and waterways all take their share in the wood trade. Some of the lakes are really inland seas, and very rough seas too. Tradition says they are bottomless – anyway, many of them are of enormous depth. Tradition might well say the forests are boundless, for what is not water in Finland is one vast and wonderful expanse of wood.

Now let us look at the life of a tree. Like Topsy "it growed;" it was not planted by man. Those vast pine forests, extending for miles and miles, actual mines of wealth, are a mere veneer to granite rocks. That is the wonderful part of it all, granite is the basis, granite distinctly showing the progress of glaciers of a former period.

Such is the foundation, and above that a foot or two of soil, sometimes less, for the rocks themselves often appear through the slight covering; but yet out of this scant earth and stone the trees are multiplied.

Standing on the top of the tower of the old castle – alas! so hideously restored – at Wiborg, one can see for miles and miles nothing but lakes and trees, and as we lingered and wondered at the flatness of the land our attention was arrested by patches of smoke.

"Forest fires, one of the curses of the land," we learned. "In hot weather there are often awful fires; look, there are five to be seen from this tower at one moment, all doing much damage and causing great anxiety, because the resin in the pines makes them burn furiously."

"How do they put them out?" we asked.

"Every one is summoned from far and near; indeed, the people come themselves when they see smoke, and all hands set to work felling trees towards the fire in order to make an open space round the flaming woods, or beating with long poles the dry burning mass which spreads the fire. It is no light labour; sometimes miles of trenching have to be dug as the only means whereby a fire can be extinguished; all are willing to help, for, directly or indirectly, all are connected with the wood trade."

Here and there where we travelled, the forests were on fire – fires luckily not caused by those chance conflagrations, which do so much harm in Finland, but duly organised to clear a certain district. Matters are arranged in this wise: when a man wants to plough more land, he selects a nice stretch of wood, saws down all the big trees, which he sledges away, the next set (in point of size) he also hews down, but leaves where they fall, with all their boughs and leaves on, till the sun dries them. Then he makes a fire in their midst, the dried leaves soon catch, and in a few hours the whole acreage is bare except for the tree trunks, which are only charred and serve later for firewood. All the farm hands, often augmented by neighbours, assist at these fires, for although a man may wish to clear two or three acres, if the flames were not watched, they would soon lay twenty or thirty bare, and perhaps destroy an entire forest. The ashes lie on the ground and become manure, so that when, during the following summer, he begins to plough, the sandy soil is fairly well-fed, and ultimately mildly prolific. He is very ingenious this peasant, and takes the greatest care not to let the flames spread beyond his appointed boundary, beating them with huge sticks, as required, and keeping the flames well in hand. The disastrous forest fires, caused by accidental circumstances, spoil the finest timber, and can only be stayed in their wild career, as we remarked elsewhere, by digging trenches, over which the roaring flames cannot pass. Such fires are one of the curses of Finland, and do almost as much harm as a flight of locusts in Morocco.

"How old are those trees we see, twenty or thirty years?"

Our friend the Kommerserådet smiled.

"Far, far more," he replied; "speaking roughly, every tree eight inches in diameter twenty feet from the ground is eighty years old, nine inches ninety years, ten inches a hundred years old, and so on."

We were amazed to think that these vast forests should be so old, for if it took so long for a tree to grow, and so many millions were felled every year, it seemed to us that the land would soon be barren.

"Not at all," our friend replied; "a forest is never cleared. Only trees which have reached a proper girth are felled. In every forest but a certain number of trees are cut each year, so that fresh ones are in a continuous stream taking their places."

Rich merchants possess their own forests, their own saw-mills, their own store houses, and even their own ships; but the bulk of exporters pay for cut timber. In hiring a forest the tenant takes it on lease for so many years with the right to fell all trees so soon as they reach certain dimensions. The doomed trees are marked, and now we must follow their after course.

In the autumn and winter they are felled and left for the first fall of snow, when they are dragged, sometimes two or three logs one behind the other fixed together with iron chains, to the nearest open road for further conveyance by sledge when the snow permits.

No single horse could move such a weight in summer, but by the aid of sledges and snow all is changed, and away gallop the little steeds down the mountain side, pushed forward at times by the weight behind. By this means the trees are conveyed to the nearest waterway.

Then the logs are stamped with the owner's registered mark and rolled upon the ice of lake or river, to await the natural transport of spring. Once the ice thaws the forests begin to move, for as "Birnam Wood marched to Dunsinane," the Finnish forests float to other lands.