полная версия

полная версияMary Queen of Scots

Disposal of Mary.

Whatever doubt there may be about these things, there is none about the events which followed. After Mary had surrendered herself to her nobles they took her to the camp, she herself riding on horseback, and Grange walking by her side. As she advanced to meet the nobles who had combined against her, she said to them that she had concluded to come over to them, not from fear, or from doubt what the issue would have been if she had fought the battle, but only because she wanted to spare the effusion of Christian blood, especially the blood of her own subjects. She had therefore decided to submit herself to their counsels, trusting that they would treat her as their rightful queen. The nobles made little reply to this address, but prepared to return to Edinburgh with their prize.

Return to Edinburgh.

The banner.

Rudeness of the populace.

The people of Edinburgh, who had heard what turn the affair had taken, flocked out upon the roads to see the queen return. They lined the waysides to gaze upon the great cavalcade as it passed. The nobles who conducted Mary thus back toward her capital had a banner prepared, or allowed one to be prepared, on which was a painting representing the dead body of Darnley, and the young prince James kneeling near him, and calling on God to avenge his cause. Mary came on, in the procession, after this symbol. They might perhaps say that it was not intended to wound her feelings, and was not of a nature to do it, unless she considered herself as taking sides with the murderers of her husband. She, however, knew very well that she was so regarded by great numbers of the populace assembled, and that the effect of such an effigy carried before her was to hold her up to public obloquy. The populace did, in fact, taunt and reproach her as she proceeded, and she rode into Edinburgh, evincing all the way extreme mental suffering by her agitation and her tears.

She expected that they were at least to take her to Holyrood; but no, they turned at the gate to enter the city. Mary protested earnestly against this, and called, half frantic, on all who heard her to come to her rescue. But no one interfered. They took her to the provost's house, and lodged her there for the night, and the crowd which had assembled to observe these proceedings gradually dispersed. There seemed, however, in a day or two, to be some symptoms of a reaction in favor of the fallen queen; and, to guard against the possibility of a rescue, the lords took Mary to Holyrood again, and began immediately to make arrangements for some more safe place of confinement still.

Bothwell's retreat.

He is pursued.

Bothwell's narrow escape.

In the mean time, Bothwell went from Carberry Hill to his castle at Dunbar, revolving moodily in his mind his altered fortunes. After some time he found himself not safe in this place of refuge, and so he retreated to the north, to some estates he had there, in the remote Highlands. A detachment of forces was sent in pursuit of him. Now there are, north of Scotland, some groups of dismal islands, the summits of submerged mountains and rocks, rising in dark and sublime, but gloomy grandeur, from the midst of cold and tempestuous seas. Bothwell, finding himself pursued, undertook to escape by ship to these islands. His pursuers, headed by Grange, who had negotiated at Carberry for the surrender of the queen, embarked in other vessels, and pressed on after him. At one time they almost overtook him, and would have captured him and all his company were it not that they got entangled among some shoals. Grange's sailors said they must not proceed. Grange, eager to seize his prey, insisted on their making sail and pressing forward. The consequence was, they ran the vessels aground, and Bothwell escaped in a small boat. As it was, however, they seized some of his accomplices, and brought them back to Edinburgh. These men were afterward tried, and some of them were executed; and it was at their trial, and through the confessions they made, that the facts were brought to light which have been related in this narrative.

He turns pirate.

Bothwell in prison.

His miserable end.

Bothwell, now a fugitive and an exile, but still retaining his desperate and lawless character, became a pirate, and attempted to live by robbing the commerce of the German Ocean. Rumor is the only historian, in ordinary cases, to record the events in the life of a pirate; and she, in this case, sent word, from time to time, to Scotland, of the robberies and murders that the desperado committed; of an expedition fitted out against him by the King of Denmark, of his being taken and carried into a Danish port; of his being held in imprisonment for a long period there, in a gloomy dungeon; of his restless spirit chafing itself in useless struggles against his fate, and sinking gradually, at last under the burdens of remorse for past crimes, and despair of any earthly deliverance; of his insanity, and, finally, of his miserable end.

Chapter X

Loch Leven Castle

1567-1568Grange of Kircaldy.

Mary's letter.

Grange, or, as he is sometimes called, Kircaldy, his title in full being Grange of Kircaldy, was a man of integrity and honor, and he, having been the negotiator through whose intervention Mary gave herself up, felt himself bound to see that the stipulations on the part of the nobles should be honorably fulfilled. He did all in his power to protect Mary from insult on the journey, and he struck with his sword and drove away some of the populace who were addressing her with taunts and reproaches. When he found that the nobles were confining her, and treating her so much more like a captive than like a queen, he remonstrated with them. They silenced him by showing him a letter, which they said they had intercepted on its way from Mary to Bothwell. It was written, they said, on the night of Mary's arrival at Edinburgh. It assured Bothwell that she retained an unaltered affection for him; that her consenting to be separated from him at Carberry Hill was a matter of mere necessity, and that she should rejoin him as soon as it was in her power to do so. This letter showed, they said, that, after all, Mary was not, as they had supposed, Bothwell's captive and victim, but that she was his accomplice and friend; and that, now that they had discovered their mistake, they must treat Mary, as well as Bothwell, as an enemy, and take effectual means to protect themselves from the one as well as from the other. Mary's friends maintain that this letter was a forgery.

Removal of Mary.

A ride at night.

They accordingly took Mary, as has been already stated, from the provost's house in Edinburgh down to Holyrood House, which was just without the city. This, however, was only a temporary change. That night they came into the palace, and directed Mary to rise and put on a traveling dress which they brought her. They did not tell her where she was to go, but simply ordered her to follow them. It was midnight. They took her forth from the palace, mounted her upon a horse, and, with Ruthven and Lindsay, two of the murderers of Rizzio, for an escort, they rode away. They traveled all night, crossed the River Forth and arrived in the morning at the Castle of Loch Leven.

Loch Leven Castle.

The square tower.

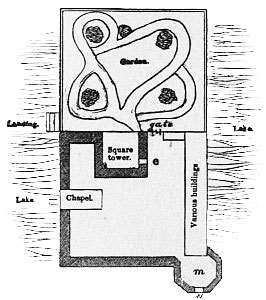

Plan of Loch Leven Castle.

The Castle of Loch Leven is on a small island in the middle of the loch. It is nearly north from Edinburgh. The castle buildings covered at that time about one half of the island, the water coming up to the walls on three sides. On the other side was a little land, which was cultivated as a garden. The buildings inclosed a considerable area. There was a great square tower, marked on the plan below, which was the residence of the family. It consisted of four or five rooms, one over the other. The cellar, or, rather, what would be the cellar in other cases, was a dungeon for such prisoners as were to be kept in close confinement. The only entrance to this building was through a window in the second story, by means of a ladder which was raised and let down by a chain. This was over the point marked e on the plan. The chain was worked at a window in the story above. There were various other apartments and structures about the square, and among them there was a small octagonal tower in the corner at m which consisted within of one room over another for three stories, and a flat roof with battlements above. In the second story there was a window, w, looking upon the water. This was the only window having an external aspect in the whole fortress, all the other openings in the exterior walls being mere loop-holes and embrasures.

The following is a general plan of Loch Leven Castle:8

Lady Douglas.

Lady Douglas Mary's enemy.

This castle was in possession of a certain personage styled the Lady Douglas. She was the mother of the Lord James, afterward the Earl of Murray, who has figured so conspicuously in this history as Mary's half brother, and at first her friend and counselor, though afterward her foe. Lady Douglas was commonly called the Lady of Loch Leven. She maintained that she had been lawfully married to James V., Mary's father, and that consequently her son, and not Mary, was the rightful heir to the crown. Of course she was Mary's natural enemy. They selected her castle as the place of Mary's confinement partly on this account, and partly on account of its inaccessible position in the midst of the waters of the lake. They delivered the captive queen, accordingly, to the Lady Douglas and her husband, charging them to keep her safely. The Lady Douglas received her, and locked her up in the octagonal tower with the window looking out upon the water.

Parties for and against Mary.

The Hamilton lords.

In the mean time, all Scotland took sides for or against the queen. The strongest party were against her; and the Church was against her, on account of their hostility to the Catholic religion. A sort of provisional government was instituted, which assumed the management of public affairs. Mary had, however, some friends, and they soon began to assemble in order to see what could be done for her cause. Their rendezvous was at the palace of Hamilton. This palace was situated on a plain in the midst of a beautiful park, near the River Clyde, a few miles from Glasgow. The Duke of Hamilton was prominent among the supporters of the queen, and made his house their head-quarters. They were often called, from this circumstance, the Hamilton lords.

Plans of Mary's enemies.

On the other hand, the party opposed to Mary made the castle of Stirling their head-quarters, because the young prince was there, in whose name they were proposing soon to assume the government. Their plan was to depose Mary, or induce her to abdicate the throne, and then to make Murray regent, to govern the country in the name of the prince until the prince should become of age. During all this time Murray had been absent in France, but they now sent urgent messages to him to return. He obeyed the summons, and turned his face toward Scotland.

Mary's tower.

Ruins.

In the mean time, Mary continued in confinement in her little tower. She was not treated like a common prisoner, but had, in some degree, the attentions due to her rank. There were five or six female, and about as many male attendants; though, if the rooms which are exhibited to visitors at the present day as the apartments which she occupied are really such, her quarters were very contracted. They consist of small apartments of an octagonal form, one over the other, with tortuous and narrow stair-cases in the solid wall to ascend from one to the other. The roof and the floors of the tower are now gone, but the stair-ways, the capacious fire-places, the loop-holes, and the one window remain, enabling the visitor to reconstruct the dwelling in imagination, and even to fancy Mary herself there again, seated on the stone seat by the window, looking over the water at the distant hills, and sighing to be free.

The scale turns against Mary.

The Hamilton lords were not strong enough to attempt her rescue. The weight of influence and power throughout the country went gradually and irresistibly into the other scale. There were great debates among the authorities of government as to what should be done. The Hamilton lords made proposals in behalf of Mary which the government could not accede to. Other proposals were made by different parties in the councils of the insurgent nobles, some more and some less hard for the captive queen. The conclusion, however, finally was, to urge Mary to resign her crown in favor of her son, and to appoint Murray, when he should return, to act as regent till the prince should be of age.

Proposals made to Mary.

They accordingly sent commissioners to Loch Leven to propose these measures to the queen. There were three instruments of abdication prepared for her to sign. By one she resigned the crown in favor of her son. By the second she appointed Murray to be regent as soon as he should return from France. By the third she appointed commissioners to govern the country until Murray should return. They knew that Mary would be extremely unwilling to sign these papers, and yet that they must contrive, in some way, to obtain her signature without any open violence; for the signature, to be of legal force, must be, in some sense, her voluntary act.

The commissioners.

The two commissioners whom they sent to her were Melville and Lindsay. Melville was a thoughtful and a reasonable man, who had long been in Mary's service, and who possessed a great share of her confidence and good will. Lindsay was, on the other hand, of an overbearing and violent temper, of very rude speech and demeanor, and was known to be unfriendly to the queen. They hoped that Mary would be induced to sign the papers by Melville's gentle persuasions; if not, Lindsay was to see what he could do by denunciations and threats.

Melville unsuccessful.

When the two commissioners arrived at the castle, Melville alone went first into the presence of the queen. He opened the subject to her in a gentle and respectful manner. He laid before her the distracted state of Scotland, the uncertain and vague suspicions floating in the public mind on the subject of Darnley's murder, and the irretrievable shade which had been thrown over her position by the unhappy marriage with Bothwell; and he urged her to consent to the proposed measures, as the only way now left to restore peace to the land. Mary heard him patiently, but replied that she could not consent to his proposal. By doing so she should not only sacrifice her own rights, and degrade herself from the position she was entitled to occupy, but she should, in some sense, acknowledge herself guilty of the charges brought against her, and justify her enemies.

Lindsay called in.

Lindsay's brutality.

Abdication.

Melville, finding that his efforts were vain, called Lindsay in. He entered with a fierce and determined air. Mary was reminded of the terrible night when he and Ruthven broke into her little supper-room at Holyrood in quest of Rizzio. She was agitated and alarmed. Lindsay assailed her with denunciations and threats of the most violent character. There ensued a scene of the most rough and ferocious passion on the one side, and of anguish, terror, and despair on the other, which is said to have made this day the most wretched of all the wretched days of Mary's life. Sometimes she sat pale, motionless, and almost stupefied. At others, she was overwhelmed with sorrow and tears. She finally yielded; and, taking the pen, she signed the papers. Lindsay and Melville took them, left the castle gate, entered their boat, and were rowed away to the shore.

Coronation of James.

This was on the 25th of July, 1567, and four days afterward the young prince was crowned at Stirling. His title was James VI. Lindsay made oath at the coronation that he was a witness of Mary's abdication of the crown in favor of her son, and that it was her own free and voluntary act. James was about one year old. The coronation took place in the chapel where Mary had been crowned in her infancy, about twenty-five years before. Mary herself, though unconscious of her own coronation, mourned bitterly over that of her son. Unhappy mother! how little was she aware, when her heart was filled with joy and gladness at his birth, that in one short year his mere existence would furnish to her enemies the means of consummating and sealing her ruin.

Ceremonies.

On returning from the chapel to the state apartments of the castle, after the coronation, the noblemen by whom the infant had been crowned walked in solemn procession, bearing the badges and insignia of the newly-invested royalty. One carried the crown. Morton, who was to exercise the government until Murray should return, followed with the scepter, and a third bore the infant king, who gazed about unconsciously upon the scene, regardless alike of his mother's lonely wretchedness and of his own new scepter and crown.

Return of Murray.

In the mean time, Murray was drawing near toward the confines of Scotland. He was somewhat uncertain how to act. Having been absent for some time in France and on the Continent, he was not certain how far the people of Scotland were really and cordially in favor of the revolution which had been effected. Mary's friends might claim that her acts of abdication, having been obtained while she was under duress, were null and void, and if they were strong enough they might attempt to reinstate her upon the throne. In this case, it would be better for him not to have acted with the insurgent government at all. To gain information on these points, Murray sent to Melville to come and meet him on the border. Melville came. The result of their conferences was, that Murray resolved to visit Mary in her tower before he adopted any decisive course.

Murray's interview with Mary.

Affecting scene.

Murray assumes the government.

Murray accordingly journeyed northward to Loch Leven, and, embarking in the boat which plied between the castle and the shore, he crossed the sheet of water, and was admitted into the fortress. He had a long interview with Mary alone. At the sight of her long-absent brother, who had been her friend and guide in her early days of prosperity and happiness, and who had accompanied her through so many changing scenes, and who now returned, after his long separation from her, to find her a lonely and wretched captive, involved in irretrievable ruin, if not in acknowledged guilt, she was entirely overcome by her emotions. She burst into tears and could not speak. What further passed at this interview was never precisely known. They parted tolerably good friends, however, and yet Murray immediately assumed the government, by which it is supposed that he succeeded in persuading Mary that such a step was now best for her sake as well as for that of all others concerned.

His warnings.

Murray, however, did not fail to warn her, as he himself states, in a very serious manner, against any attempt to change her situation. "Madam," said he, "I will plainly declare to you what the sources of danger are from which I think you have most to apprehend. First, any attempt, of whatever kind, that you may make to create disturbance in the country, through friends that may still adhere to your cause, and to interfere with the government of your son; secondly, devising or attempting any plan of escape from this island; thirdly, taking any measures for inducing the Queen of England or the French king to come to your aid; and, lastly, persisting in your attachment to Earl Bothwell." He warned Mary solemnly against any and all of these, and then took his leave. He was soon after proclaimed regent. A Parliament was assembled to sanction all the proceedings, and the new government was established, apparently upon a firm foundation.

Mary remained, during the winter, in captivity, earnestly desiring, however, notwithstanding Murray's warning, to find some way of escape. She knew that there must be many who had remained friends to her cause. She thought that if she could once make her escape from her prison, these friends would rally around her, and that she could thus, perhaps, regain her throne again. But strictly watched as she was, and in a prison which was surrounded by the waters of a lake, all hope of escape seemed to be taken away.

The young Douglases.

Their interest in Mary.

Now there were, in the family of the Lord Douglas at the castle, two young men, George and William Douglas. The oldest, George, was about twenty-five years of age, and the youngest was seventeen. George was the son of Lord and Lady Douglas who kept the castle. William was an orphan boy, a relative, who, having no home, had been received into the family. These young men soon began to feel a strong interest in the beautiful captive confined in their father's castle, and, before many months, this interest became so strong that they began to feel willing to incur the dangers and responsibilities of aiding her in effecting her escape. They had secret conferences with Mary on the subject. They went to the shore on various pretexts, and contrived to make their plans known to Mary's friends, that they might be ready to receive her in case they should succeed.

Plan for Mary's escape.

The plan at length was ripe for execution. It was arranged thus. The castle not being large, there was not space within its walls for all the accommodations required for its inmates; much was done on the shore, where there was quite a little village of attendants and dependents pertaining to the castle. This little village has since grown into a flourishing manufacturing town, where a great variety of plaids, and tartans, and other Scotch fabrics are made. Its name is Kinross. Communication with this part of the shore was then, as now, kept up by boats, which generally then belonged to the castle, though now to the town.

The laundress.

The disguise.

On the day when Mary was to attempt her escape, a servant woman was brought by one of the castle boats from the shore with a bundle of clothes for Mary. Mary, whose health and strength had been impaired by her confinement and sufferings, was often in her bed. She was so at this time, though perhaps she was feigning now more feebleness than she really felt. The servant woman came into her apartment and undressed herself, while Mary rose, took the dress which she laid aside, and put it on as a disguise. The woman took Mary's place in bed. Mary covered her face with a muffler, and, taking another bundle in her hand to assist in her disguise, she passed across the court, issued from the castle gate, went to the landing stairs, and stepped into the boat for the men to row her to the shore.

Escape.

Discovery.

The oarsmen, who belonged to the castle, supposing that all was right, pushed off, and began to row toward the land. As they were crossing the water, however, they observed that their passenger was very particular to keep her face covered, and attempted to pull away the muffler, saying, "Let us see what kind of a looking damsel this is." Mary, in alarm, put up her hands to her face to hold the muffler there. The smooth, white, and delicate fingers revealed to the men at once that they were carrying away a lady in disguise. Mary, finding that concealment was no longer possible, dropped her muffler, looked upon the men with composure and dignity, told them that she was their queen, that they were bound by their allegiance to her to obey her commands, and she commanded them to go on and row her to the shore.

Mary's return.

Banishment of George Douglas.

The men decided, however, that their allegiance was due to the lord of the castle rather than to the helpless captive trying to escape from it. They told her that they must return. Mary was not only disappointed at the failure of her plans, but she was now anxious lest her friends, the young Douglases, should be implicated in the attempt, and should suffer in consequence of it. The men, however, solemnly promised her, that if she would quietly return, they would not make the circumstances known. The secret, however, was too great a secret to be kept. In a few days it all came to light. Lord and Lady Douglas were very angry with their son, and banished him, together with two of Mary's servants, from the castle. Whatever share young William Douglas had in the scheme was not found out, and he was suffered to remain. George Douglas went only to Kinross. He remained there watching for another opportunity to help Mary to her freedom.

![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](/covers_200/36364270.jpg)