полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

Let a few examples illustrate the effectiveness of irrigation. In the neighborhood of Weissensfels, 7½ hectares of well-watered meadows produced 480 cwt. of after-grass; 5 contiguous hectares of meadow land of the same quality, but not watered, yielded only 32 cwt. The former had, accordingly, a crop ten times as large as the latter. Near Reisa in Saxony, the irrigation of 65 acres of meadow lands raised their revenue from 5,850 marks to 11,100 marks. The expensive outlays paid. Besides the Mark there are in Germany other vast tracts, whose soil, consisting mainly of sand, yields but poor returns, even when the summer is wet. Crossed and irrigated by canals, and their soil improved, these lands would within a short time yield five and ten times as much. There are examples in Spain of the yield of well-irrigated lands exceeding thirty-seven fold that of others that are not irrigated. Let there but be water, and increased volumes of food are conjured into existence.

Where are the private individuals, where the States, able to operate upon the requisite scale? When, after long decades of bitter experience, the State finally yields to the stormy demands of a population that has suffered from all manner of calamities, and only after millions of values have been destroyed, how slow, with what circumspection, how cautious does it proceed! It is so easy to do too much, and the State might by its precipitancy lose the means with which to build some new barracks for the accommodation of a few regiments. Then also, if one is helped "too much," others come along, and also want help. "Man, help yourself and God will help you," thus runs the bourgeois creed. Each for himself, none for all. And thus, hardly a year goes by without once, twice and oftener more or less serious freshets from brooks, rivers or streams occurring in several provinces and States: vast tracts of fertile lands are then devastated by the violence of the floods, and others are covered with sand, stone and all manner of debris; whole orchard plantations, that demanded tens of years for their growth, are uprooted; houses, bridges, dams are washed away; railroad tracks torn up; cattle, not infrequently human beings also, are drowned; soil improvements are carried off; crops ruined. Vast tracts, exposed to frequent inundations, are cultivated but slightly, lest the loss be double.

On the other hand, unskilful corrections of the channels of large rivers and streams, – undertaken in one-sided interests, to which the State ever yields readily in the service of "trade and transportation" – increase the dangers of freshets. Extensive cutting down of forests, especially on highlands and for private profit, adds more grist to the flood mill. The marked deterioration of the climate and decreased productivity of the soil, noticeable in the provinces of Prussia, Pomerania, the Steuermark, Italy, France, Spain, etc., is imputed to this vandalic devastation of the woods, done in the interest of private parties.

Frequent freshets are the consequence of the dismantling of mountain woodlands. The inundations of the Rhine, the Oder and the Vistula are ascribed mainly to the devastation of the woods in Switzerland, Galicia and Poland; and likewise in Italy with regard to the Po. Due to the baring of the Carnian Alps, the climate of Triest and Venice has materially deteriorated. Madeira, a large part of Spain, vast and once luxurious fields of Asia Minor have in a great measure forfeited their fertility through the same causes.

It goes without saying that Socialist society will not be able to accomplish all these great tasks out-of-hand. But it can and will undertake them, with all possible promptness and with all the powers at its command, seeing that its sole mission is to solve problems of civilization and to tolerate no hindrance. Thus it will in the course of time solve problems and accomplish feats that modern society can give no thought to, and the very thought of which gives it the vertigo.

The cultivation of the soil will, accordingly, be mightily improved in Socialist society, through these and similar measures. But other considerations, looking to the proper exploitation of the soil, are added to these. To-day, many square miles are planted with potatoes, which are to be applied mainly to the distilling of brandy, an article consumed almost exclusively by the poor classes of the population. Liquor is the only stimulant and "care-dispeller" that they are able to procure. The population of Socialist society needs none of that, hence the raising of potatoes and corn for that purpose, together with the labor therein expended, are set free for the production of healthy food.196 The speculative purposes that our most fertile fields are put to in the matter of the sugar beet for the exportation of sugar, have been pointed out in a previous chapter. About 400,000 hectares of the best wheat fields are yearly devoted to the cultivation of sugar beet, in order to supply England, the United States and Northern Europe with sugar. The countries whose climate favors the growth of sugar cane succumb to this competition. Furthermore, our system of a standing army, the disintegration of production, the disintegration of the means of transportation and communication, the disintegration of agriculture, etc., – all these demand hundreds of thousands of horses, with the corresponding fields to feed them and to raise colts. The completely transformed social and political conditions free the bulk of the lands that are now given up to these various purposes; and again large areas and rich labor-power are reclaimed for purposes of civilization. Latterly, extensive fields, covering many square kilometers, have been withdrawn from cultivation, being needed for the manoeuvering and exercising of army corps in the new methods of warfare and long distance firearms. All this falls away.

The vast field of agriculture, forestry and irrigation has become the subject of an extensive scientific literature. No special branch has been left untouched: irrigation and drainage, forestry, the cultivation of cereals, of leguminous and tuberous plants, of vegetables, of fruit trees, of berries, of flowers and ornamental plants; fodder for cattle raising; meadows; rational methods of breeding cattle, fish and poultry and bees, and the utilization of their excrements; utilization of manure and refuse in agriculture and manufacture; chemical examinations of seeds and of the soil, to ascertain its fitness for this or that crop; investigations in the rotations of crops and in agricultural machinery and implements; the profitable construction of agricultural buildings of all nature; the weather; – all have been drawn within the circle of scientific treatment. Hardly a day goes by without some new discovery, some new experience being made towards improving and ennobling one or other of these several branches. With the work of J. v. Liebig, the cultivation of the soil has become a science, indeed, one of the foremost and most important of all, a science that since then has attained a vastness and significance unique in the domain of activity in material production. And yet, if we compare the fullness of the progress made in this direction with the actual conditions prevailing in agriculture to-day, it must be admitted that, until now, only a small fraction of the private owners have been able to turn the progress to advantage, and among these there naturally is none who did not proceed from the view point of his own private interests, acted accordingly, kept only that in mind, and gave no thought to the public weal. The large majority of our farmers and gardeners, we may say 98 per cent. of them, are in no wise in condition to utilize all the advances made and advantages that are possible: they lack either the means or the knowledge thereto, if not both: as to the others, they simply do as they please. Socialist society finds herein a theoretically and practically well prepared field of activity. It need but to fall to and organize in order to attain wonderful results.

The highest possible concentration of productions affords, of itself, mighty advantages. Hedges, making boundary lines, wagon roads and footpaths between the broken-up holdings are removed, and yield some more available soil. The application of machinery is possible only on large fields: agricultural machinery of fullest development, backed by chemistry and physics could to-day transform unprofitable lands, of which there are not a few, into fertile ones. The application of accumulated electric power to agricultural machinery – plows, harrows, rollers, sowers, mowers, threshers, seed-assorters, chaff-cutters, etc. – is only a question of time. Likewise will the day come when electricity will move from the fields the wagons laden with the crops: draught cattle can be spared. A scientific system of fertilizing the fields, hand in hand with thorough management, irrigation and draining will materially increase the productivity of the land. A careful selection of seeds, proper protection against weeds – in itself a head much sinned against to-day – sends up the yield still higher.

According to Ruhland, a successful war upon cereal diseases would of itself suffice to render superfluous the present importation of grain into Germany.197 Seeding, planting and rotation of crops, being conducted with the sole end in view of raising the largest possible volume of food, the object is then obtainable.

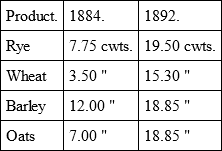

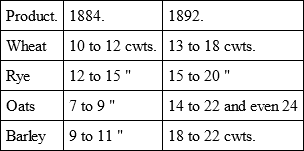

What may be possible even under present conditions is shown by the management of the Schnistenberg farm in the Rhenish Palatinate. In 1884 the same fell into the hand of a new tenant, who, in the course of eight years, raised three or four times as much as his predecessor.198 The said property is situated 320 meters above the level of the sea, 286 acres in size, of which 18 are meadows, and has generally unfavorable soil, 30 acres being sandy, 60 stony, 55 sand loam and 123 hard loam. The new method of cultivation had astonishing results. The crops rose from year to year. The increase during the period of 1884-1892 was as follows per acre:

The neighboring community of Kiegsfeld, the witness of this marvelous development, followed the example and reached similar results on its own ground. The yield per acre was on an average this:

Such results are eloquent enough.

The cultivation of fruits, berries and garden vegetables will reach a development hardly thought possible. How unpardonably is being sinned at present in these respects, a look at our orchards will show. They are generally marked by a total absence of proper care. This is true of the cultivation of fruit trees even in countries that have a reputation for the excellence of these; Wurtemberg, for instance. The concentration of stables, depots for implements and manure and methods of feeding – towards which wonderful progress has been made, but which can to-day be applied only slightly – will, when generally introduced, materially increase the returns in raising cattle, and thereby facilitate the procurement of manure. Machinery and implements of all sorts will be there in abundance, very differently from the experience of ninety-nine one hundredths of our modern farmers. Animal products, such as milk, eggs, meat, honey, hair, wool, will be obtained and utilized scientifically. The improvements and advantages in the dairy industry reached by the large dairy associations is known to all experts, and ever new inventions and improvements are daily made. Many are the branches of agriculture in which the same and even better can be done. The preparation of the fields and the gathering of the crops are then attended to by large bodies of men, under skilful use of the weather, such as is to-day impossible. Large drying houses and sheds allow crops being gathered even in unfavorable weather, and save losses that are to-day unavoidable, and which, according to v. d. Goltz, often are so severe that, during a particularly rainy year, from eight to nine million marks worth of crops were ruined in Mecklenburg, and from twelve to fifteen in the district of Koenigsberg.

Through the skilful application of artificial heat and moisture on a large scale in structures protected from bad weather, the raising of vegetables and all manner of fruit is possible at all seasons in large quantities. The flower stores of our large cities have in mid-winter floral exhibitions that vie with those of the summer. One of the most remarkable advances made in the artificial raising of fruit is exemplified by the artificial vineyard of Garden-Director Haupt in Brieg, Silesia, which has found a number of imitators, and was itself preceded long before by a number of others in other countries, England among them. The arrangements and the results obtained in this vineyard were so enticingly described in the "Vossische Zeitung" of September 27, 1890, that we have reproduced the account in extracts:

"The glass-house is situated upon an approximately square field of 500 square meters, i. e., one-fifth of an acre. It is 4.5 to 5 meters high, and its walls face north, south, east and west. Twelve rows of double fruit walls run inside due north and south. They are 1.8 meters apart from each other and serve at the same time as supports to the flat roof. In a bed 1.25 meters deep, resting on a bank of earth 25 centimeters strong and which contains a net of drain and ventilation pipes, – a bed 'whose hard ground is rendered loose, permeable and fruitful through chalk, rubbish, sand, manure in a state of decomposition, bonedust and potash' – Herr Haupt planted against the walls three hundred and sixty grape vines of the kind which yields the noblest grape juice in the Rhinegau: – white and red Reissling and Tramine, white and blue Moscatelle and Burgundy.

"The ventilation of the place is effected by means of large fans, twenty meters long, attached to the roof, besides several openings on the side-walls. The fans can be opened and shut by means of a lever, fastened on the roof provided with a spindle and winch, and they can be made safe against all weather. For the watering of the vines 26 sprinklers are used, which are fastened to rubber pipes 1.25 meters long, and that hang down from a water tank. Herr Haupt introduced, however, another ingenious contrivance for quickly and thoroughly watering his 'wine-hall' and his 'vineyard', to wit, an artificial rain producer. On high, under the roof, lie four long copper tubes, perforated at distances of one-half meter. The streams of water that spout upward through these openings strike small round sieves made of window gauze and, filtered through these, are scattered in fine spray. To thoroughly water the vines by means of the rubber pipes requires several hours. But only one faucet needs to be turned by this second contrivance and a gentle refreshing rain trickles down over the whole place upon the grape vines, the beds and the granite flags of the walks. The temperature can be raised from 8 to 10 degrees R. above the outside air without any artificial contrivance, and simply through the natural qualities of the glass-house. In order to protect the vines from that dangerous and destructive foe, the vine louse, should it show itself, it is enough to close the drain and open all the water pipes. The inundation of the vines, thus achieved, the enemy can not withstand. The glass roof and walls protect the vineyard from storms, cold, frost and superfluous rain; in cases of hail, a fine wire-netting is spread over the same; against drought the artificial rain system affords all the protection needed. The vine-dresser of such a vineyard is his own weather-maker, and he can laugh at all the dangers from the incalculable whims and caprices of indifferent and cruel Nature, – dangers that ever threaten with ruin the fruit of the vine cultivator.

"What Herr Haupt expected happened. The vines thrived remarkably under the uniformly warm climate. The grapes ripened to their fullest, and as early as the fall of 1885 they yielded a juice not inferior to that generally obtained in the Rhinegau in point of richness of sugar and slightness of sourness. The grapes thrived equally the next year and even during the unfavorable year of 1887. On this space, when the vines have reached their full height of 5 meters, and are loaded with their burden of swollen grapes, 20 hectoliters of wine can be produced yearly, and the cost of a bottle of noble wine will not exceed 40 pennies.

"There is no reason imaginable why this process should not be conducted upon a large scale like any other industry. Glass-houses of the nature of this one on one-fifth of an acre can be undoubtedly raised upon a whole acre with equal facilities of ventilation, watering, draining and rain-making. Vegetation will start there several weeks sooner than in the open, and the vine-shoots remain safe from May frosts, rain and cold while they blossom; from drought during the growth of the grapes; from pilfering birds and grape thieves and from dampness while they ripen; finally from the vine-louse during the whole year and can hang safely deep into November and December. In his address, held in 1888 to the Society for the Promotion of Horticulture, and from which I have taken many a technical expression in this description of the 'Vineyard', the inventor and founder of the same closed his words with this alluring perspective of the future: 'Seeing that this vine culture can be carried on all over Germany, especially on otherwise barren, sandy or stony ground, such as, for instance, the worst of the Mark, that can be made arable and watered, it follows that the great interests in the cultivation of the soil receive fresh vigor from "vineyards under glass." I would like to call this industry "the vineyard of the future".'

"Just as Herr Haupt has furnished the practical proof that on this path an abundance of fine and healthy grapes can be drawn from the vine, he has also proved by his own pressing of the same what excellent wine they can yield. More thorough, more experienced, better experts and tried wine-drinkers and connoisseurs than myself have, after a severe test, bestowed enthusiastic praise upon the Reissling of the vintage of '88, upon the Tramine and Moscatelle of the vintage of '89, and upon the Burgundy of the vintage of '88, pressed from the grapes of this 'vineyard'. It should also be mentioned that this 'vineyard' also affords sufficient space for the cultivation of other side and twin plants. Herr Haupt raises between every two vines one rose bush, that blossoms richly in April and May; against the east and west walls he raises peaches, whose beauty of blossom must impart in April an appearance of truly fairy charm to this wine palace."

The enthusiasm with which the reporter describes this artificial "vineyard" in a serious paper testifies to the deep impression made upon him by this extraordinary artificial cultivation. There is nothing to prevent similar establishments, on a much more stupendous scale and for other branches of vegetation. The luxury of a double crop is obtainable in many agricultural products. To-day all such undertakings are a question of money, and their products are accessible only to the privileged classes. A Socialist society knows no other question than that of sufficient labor-power. If that is in existence, the work is done in the interest of all.

Another new invention on the field of food is that of Dr. Johann Hundhausen of Hamm in Westphalia, who succeeded in extracting the albumen of wheat – the secret of whose utilization in the legume was not yet known – in the shape of a thoroughly nutritive flour. This is a far-reaching invention. It is now possible to render the albumen of plants useful in substantial form for human food.

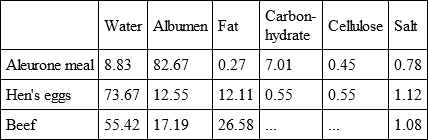

The inventor erected a large factory which produces vegetal albumen or aleurone meal from 80 to 83 per cent. of albumen, and a second quality of about 50 per cent. That the so-called aleurone meal represents a very concentrated albuminous food appears from the following comparison with our best elements of nourishment:

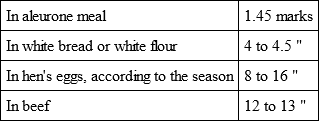

Aleurone meal is not only eaten directly, it is also used as a condiment in all sorts of bakery products, as well as soups and vegetables. Aleurone meal substitutes in a high degree meat preserves in point of nutrition; moreover, it is by far the cheapest albumen obtainable to-day. One kilogram of albumen costs:

Beef, accordingly, is about eight times dearer, as albuminous food, than aleurone meal; eggs five times as dear; white bread or common white flour about three times as dear. Aleurone meal also has the advantage that, with the addition of about one-eighth of the weight of a potato, it not only furnishes a considerable quantity of albumen to the body, but produces a complete digestion of the starch contained in the potato. Dogs, that have a nose for albumen, eat aleurone meal with the same avidity as meat, even if they otherwise refuse bread, and they are then better able to stand hardships.

Aleurone meal, as a dry vegetal albumen, is of great use as food on ships, in fortresses and in military hospitals during war. It renders large supplies of meat unnecessary. At present aleurone meal is a side product in starch factories. Within short, starch will become a side product of aleurone meal. A further result will be that the cultivation of cereals will crowd out that of potatoes and other less productive food plants; the volume of nutrition of a given field of wheat or rye is tripled or quadrupled at one stroke.

Dr. Rudolf Meyer of Vienna, whose attention was called by us to the aleurone meal says199 that he furnished himself with a quantity of it and had it examined on June 19, 1893, by the bureau of experiments of the Board of Soil Cultivation of the Kingdom of Bohemia. The examination fully confirmed our statements. For further details Meyer's work should be read. Meyer also calls attention to a discovery made by Otto Redemann of Bockenheim near Frankfort-on-the-Main. After granulating the peanut and removing its oil, he analyzed its component elements of nutrition. The analysis showed 47 per cent. of albumen, 19 of fat and 19 of starch – altogether 2,135 units of nutritious matter in one kilo. According to this analysis the peanut is one of the most nutritious vegetal products. The pharmacist Rud. Simpson of Mohrungen discovered a process by which to remove the bitterness from the lupine, which, as may be known, thrives best on sandy soil, and is used both as fodder and as a fertilizer; and he then produced from it a meal, which, according to expert authority, baked as bread tastes very good, is solid, is said to be more nutritious than rye-bread, and, besides all that, much cheaper.

Even under present conditions a regular revolution is plowing its way in the matter of human food. The utilization of all these discoveries is, however, slow, for the reason that mighty classes – the farmer element together with its social and political props – have the liveliest interest in suppressing them. To our agrarians, a good crop is to-day a horror – although the same is prayed for in all the churches – because it lowers prices. Consequently, they are no wise anxious for a double and threefold nutritive power of their cereals; it would likewise tend to lower prices. Present society is everywhere at fisticuffs with its own development.

The preservation of the soil in a state of fertility depends primarily upon fertilization. The obtaining of fertilizers is, accordingly, for future society also one of the principal tasks.200 Manure is to the soil what food is to man, and just as every kind of food is not equally nourishing to man, neither is every kind of manure of equal benefit to the soil. The soil must receive back exactly the same chemical substances that it gave up through a crop; and the chemical substances especially needed by a certain vegetable must be given to the soil in larger quantities. Hence the study of chemistry and its practical application will experience a development unknown to-day.

Animal and human excrements are particularly rich in the chemical elements that are fittest for the reproduction of human food. Hence the endeavor must be to secure the same in the fullest quantity and cause its proper distribution. On this head too modern society sins grievously. Cities and industrial centers, that receive large masses of foodstuffs, return to the soil but a slight part of their valuable offal.201 The consequence is that the fields, situated at great distances from the cities and industrial centers, and which yearly send their products to the same, suffer greatly from a dearth of manure; the offal that these farms themselves yield is often not enough, because the men and beasts who live on them consume but a small part of the product. Thus frequently a soil-vandalism is practiced, that cripples the land and decreases the crops. All countries that export agricultural products mainly, but receive no manure back, inevitably go to ruin through the gradual impoverishment of the soil. This is the case with Hungary, Russia, the Danubian Principalities, North America, etc. Artificial fertilizers, guano in particular, indeed substitute the offal of men and beasts; but many farmers can not obtain the same in sufficient quantity; it is too dear; at any rate, it is an inversion of nature to import manure from great distances, while it is allowed to go to waste nearby.