полная версия

полная версияWoman under socialism

With Laveleye, Schaeffle also detects in the changed character of the family of our days the effect of social development. He says:131 "It is true that the tendency described in Chapter II, to reduce and limit the family to its specific functions is traceable throughout history. The family relinquishes one provisional and temporary function after the other. In so far as it officiated only in a surrogate and gap-filling capacity it makes way to independent institutions for law, order, authority, divine service, education, technique, etc., as soon as these institutions take shape."

Women are pressing even further, though as yet only in a minority, and only a fraction of these with clear aims. They aspire to measure their power with men, not on the industrial field alone; they aspire not only after a freer and more independent position in the family; they also aspire at turning their mental faculties to the higher walks of life. The favorite objection raised against them is that they are not fit for such pursuits, not being intended therefor by Nature. The question of engaging in the higher professional occupations concerns at present only a small number of women in modern society; it is, however, important in point of principle. The large majority of men believe in all seriousness that, mentally as well, woman must ever remain subordinate to them, and, hence, has no right to equality. They are, accordingly, the most determined opponents of woman's aspirations.

The self-same men, who raise no objection whatever to the employment of woman in occupations, many of which are very exhausting, often dangerous, threaten the impairment of her feminine physique and violently compel her to sin against her duties as a mother, – these self-same men would exclude her from pursuits in which these obstacles and dangers are much slighter, and which are much better suited to her delicate frame.

Among the learned men, who in Germany want to hear nothing of the admission of women to the higher studies, or who will yield only a qualified assent, and express themselves publicly on the subject are Prof. L. Bischoff, Dr. Ludwig Hirt, Prof. H. Sybel, L. von Buerenbach, Dr. E. Reich, and many others. Notedly has the livelier agitation, recently set on foot, for the admission of women to the Universities, incited a strong opposition against the plan in Germany. The opposition is mainly directed against woman's qualifications for the study of medicine. Among the opponents are found Pochhammer, Fehling, S. Binder, Waldeyer, Hegar, etc. Von Buerenbach is of the opinion that both the admission to and the fitness of woman for science can be disposed of with the argument that, until now, no genius has arisen among woman, and hence woman is manifestly unfit for philosophic studies. It seems the world has had quite enough of its male philosophers: it can, without injury to itself, well afford to dispense with female. Neither does the objection that the female sex has never yet produced a genius seem to us either to hold water, or to have the weight of a demonstration. Geniuses do not drop down from the skies; they must have opportunity to form and mature. This opportunity woman has lacked until now, as amply shown by our short historic sketch. For thousands of years she has been oppressed, and she has been deprived or stunted in the opportunity and possibility to unfold her mental faculties. It is as false to reason that the female sex is bereft of genius, by denying all spark of genius to the tolerably large number of great women, as it would be to maintain that there were no geniuses among the male sex other than the few who are considered such. Every village schoolmaster knows what a mass of aptitudes among his pupils never reach full growth, because the possibilities for their development are absent. Aye, there is not one, who, in his walk through life, has not become acquainted, some with more, others with fewer persons of whom it had to be said that, had they been able to mature under more favorable circumstances, they would have been ornaments to society, and men of genius. Unquestionably the number of men of talent and of genius is by far larger among the male sex than those that, until now, have been able to reveal themselves: social conditions did not allow the others to develop. Precisely so with the faculties of the female sex, a sex that for centuries has been held under, hampered and crippled, far worse than any other subject beings. We have absolutely no measure to-day by which to gauge the fullness of mental powers and faculties that will develop among men and women so soon as they shall be able to unfold amid natural conditions.

It is with mankind as in the vegetable kingdom. Millions of valuable seeds never reach development because the ground on which they fall is unfavorable, or is taken up by weeds that rob the young and better plant of air, light and nourishment. The same laws of Nature hold good in human life. If a gardener or planter sought to maintain with regard to a given plant that it could not grow, although he made no trial, perhaps even hindered its growth by wrong treatment, such a man would be pronounced a fool by all his intelligent neighbors. Nor would he fare any better if he declined to cross one of his female domestic animals with, a male of higher breed, to the end of producing a better animal.

There is no peasant in Germany to-day so ignorant as not to understand the advantage of such treatment of his trees or animals – provided always his means allow him to introduce the better method. Only with regard to human beings do even men of learning deny the force of that which with regard to all other matters, they consider an established law. And yet every one, even without being a naturalist, can make instructive observations in life. Whence comes it that the children of peasants differ from city children? It comes from the difference in their conditions of life and education.

The one-sidedness, inherent in the education for one calling, stamps man with a peculiar character. A clergyman or a schoolmaster is generally and easily recognized by his carriage and mien; likewise an officer, even when in civilian dress. A shoe maker is easily told from a tailor, a joiner from a locksmith. Twin brothers, who closely resembled each other in youth, show in later years marked differences if their occupations are different, if one had hard manual work, for instance, as a smith, the other the study of philosophy for his duty. Heredity, on one side, adaptation on the other, play in the development of man, as well as of animals, a decisive role. Indeed, man is the most bending and pliable of all creatures. A few years of changed life and occupation often suffice to make quite a different being out of the same man. Nowhere does rapid external change show itself more strikingly than when a person is transferred from poor and reduced, to materially improved circumstances. It is in his mental make-up that such a person will be least able to deny his antecedents, but that is due to the circumstance that, with most of such people, after they have reached a certain age, the desire for intellectual improvement is rarely felt; neither do they need it. Such an upstart rarely suffers under this defect. In our days, that look to money and material means, people are far readier to bow before the man with a large purse, than before a man of knowledge and great intellectual gifts, especially if he has the misfortune of being poor and rankless. Instances of this sort are furnished every day. The worship of the golden calf stood in no age higher than in this, – whence it comes that we are living "in the best possible world."

The strongest evidence of the effect exercised upon man by radically different conditions of life is furnished in our several industrial centers. In these centers employer and employe present externally such a contrast as if they belonged to different races. Although accustomed to the contrast, it struck us almost with the shock of a surprise on the occasion of a campaign mass meeting, that we addressed in the winter of 1877 in an industrial town of the Erzgebirge region. The meeting, at which a debate was to be held between a liberal professor and ourselves, was so arranged that both sides were equally represented. The front part of the hall was taken by our opponents, – almost without exception, healthy, strong, often large figures; in the rear of the hall and in the galleries stood workingmen and small tradesmen, nine-tenths of the former weavers, – mostly short, thin, shallow-chested, pale-faced figures, with whom worry and want looked out at every pore. One set represented the full-stomached virtue and solvent morality of bourgeois society; the other set, the working bees and beasts of burden, on the product of whose labor the gentlemen made so fine an appearance. Let both be placed for one generation under equally favorable conditions, and the contrast will vanish with most; it certainly is blotted out in their descendants.

It is also evident that, in general, it is harder to determine the social standing of women than of men. Women adapt themselves more readily to new conditions; they acquire higher manners more quickly. Their power of accommodation is greater than that of more clumsy man.

What to a plant are good soil, light and air, are to man healthy social conditions, that allow him to unfold his powers. The well known saying: "Man is what he eats," expresses the same thought, although somewhat one-sidedly: The question is not merely what man eats; it embraces his whole social posture, the social atmosphere in which he moves, that promotes or stunts his physical and mental development, that affects, favorably or unfavorably, his sense of feeling, of thought, and of action. Every day we see people, situated in favorable material conditions, going physically and morally to wreck, simply because, beyond the narrower sphere of their own domestic or personal surroundings, unfavorable circumstances of a social nature operate upon them, and gain such overpowering ascendency that they switch them on wrong tracks. The general conditions under which a man lives are even of far greater importance than those of the home and the family. If the conditions for social development are equal to both sexes, if to neither there stand any obstacles in the way, and if the social state of society is a healthy one, then woman also will rise to a point of perfection in her being, such as we can have no full conception of, such conditions having hitherto been absent in the history of the development of the race. That which some women are in the meantime achieving, leaves no doubt upon this head: these rise as high above the mass of their own sex as the male geniuses do above the mass of theirs. Measured with the scale usually applied to Princes, women have, on an average, displayed greater talent than men in the ruling of States. As illustrations, let Isabella and Blanche of Castile be quoted; Elizabeth of Hungary; Catharine Sforza, the Duchess of Milan and Imola; Elizabeth of England; Catharine of Russia; Maria Theresa, etc. Resting upon the fact that, in all races and all parts of the world, women have ruled with marked ability, even over the wildest and most turbulent hordes, Burbach makes the statement that, in all probability, women are fitter for politics than men.132 For the rest, many a great man in history would shrink considerably, were it only known What he owes to himself, and what to others. Count Mirabeau, for instance, is described by German historians, von Sybel among them, as one of the greatest lights of the French Revolution: and now research has revealed the fact that this light was indebted for the concept of almost all of his speeches to the ready help of certain scholars, who worked for him in secret, and whom he understood to utilize. On the other hand, apparitions like those of a Sappho, a Diotima of the days of Socrates, a Hypatia of Alexander, a Madame Roland, Madame de Stael, George Sand, etc., deserve the greatest respect, and eclipse many a male star. The effect of women as mothers of great men is also known. Woman has achieved all that was possible to her under the, to her, as a whole, most unfavorable circumstances; all of which justifies the best hopes for the future. As a matter of fact, only the second half of the nineteenth century began to smooth the way for the admission of women in large numbers to the race with men on various fields; and quite satisfactory are the results attained.

But suppose that, on an average, women are not as capable of higher development as men, that they cannot grow into geniuses and great philosophers, was this a criterion for men when, at least according to the letter of the law, they were placed on a footing of equality with "geniuses" and "philosophers?" The identical men of learning, who deny higher aptitudes to woman, are quite inclined to do the same to artisans and workingmen. When the nobility appeals to its "blue" blood and to its genealogical tree, these men of learning laugh in derision and shrug their shoulders; but as against the man of lower rank, they consider themselves an aristocracy, that owes what it is, not to more favorable conditions of life, but to its own talent alone. The same men who, on one field, are among the freest from prejudice, and who hold him lightly who does not think as liberally as themselves, are, on another field, – the moment the interests of their rank and class, or their vanity and self-esteem are concerned – found narrow to the point of stupidity, and hostile to the point of fanaticism. The men of the upper classes look down upon the lower; and so does almost the whole sex upon woman. The majority of men see in woman only an article of profit and pleasure; to acknowledge her an equal runs against the grain of their prejudices: – woman must be humble and modest; she must confine herself exclusively to the house and leave all else to the men, the "lords of creation," as their domain: woman must, to the utmost, bridle her own thoughts and inclinations, and quietly accept what her Providence on earth – father or husband – decrees. The nearer she approaches this standard, all the more is she praised as "sensible, modest and virtuous," even though, as the result of such constraint, she break down under the burden of physical and moral suffering. What absurdity is it not to speak of the "equality of all" and yet seek to keep one-half of the human race outside of the pale!

Woman has the same right as man to unfold her faculties and to the free exercise of the same: she is human as well as he: like him, she should be free to dispose of herself as her own master. The accident of being born a woman, makes no difference. To exclude woman from equality on the ground that she was born female and not male – an accident for which man is as little responsible as she – is as inequitable, as would be to make rights and privileges dependent upon the accident of religion or political bias; and as senseless as that two human beings must look upon each other as enemies on the ground that the accident of birth makes them of different stock and nationality. Such views are unworthy of a truly free being. The progress of humanity lies in removing everything that holds one being, one class, one sex, in dependence and in subjection to another. No inequality is justified other than that which Nature itself establishes in the differences between one individual and another, and for the fulfillment of the purpose of Nature. The natural boundaries no sex can overstep: it would thereby destroy its own natural purpose.

The adversaries of full equality for woman play as their trump card the claim that woman has a smaller brain than man, and that in other qualities, besides, she is behind man, hence her permanent inferiority (subordination) is demonstrated. It is certain that man and woman are beings of different sexes; that they are furnished with different organs, corresponding to the sex purpose of each; and that, owing to the functions that each sex must fill to accomplish the purpose of Nature, there are a series of other differences in their physiologic and psychic conditions. These are facts that none can deny and none will deny; nevertheless, they justify no distinction in the social and political rights of man and woman. The human race, society, consists of both sexes; both are indispensable to its existence and progress. Even the greatest male genius was born of a mother, to whom frequently he is indebted for the best part of himself. By what right can woman be refused equality with man?

Based upon information furnished us by a medical friend, we shall here sketch with a few strokes the essential differences, that, according to leading authorities, manifest themselves in the physical and mental qualities of man and woman. The bodily size of man and woman stands, on an average, in the relation of 100 to 93.2. The bones of woman are shorter and thinner, the chest smaller, wider, deeper and flatter. Other differences depend directly upon the sex purpose. The muscles of woman are not as massive. The weight of the heart is 310 grains in man, 255 in woman.

The composition of the blood in man and woman is as follows: Water, man, 77.19; woman, 79.11. Solid matter, man, 22.10; woman, 20.89. Blood corpuscles, man, 14.10; woman, 12.79. Number of blood corpuscles in a cubic millimeter of blood, man, 4½ to 5 millions; woman, 4 to 4½ millions. According to Meynert, the weight of the brain of man is from 1,018 to 1,925 grams; of woman, from 820 to 1,565; or in the relation of 100 to 90.93. LeBon and Bischoff agree that, while weight of brain corresponds with size of body, nevertheless short people have relatively larger brains. With woman, the smaller size of the heart, the narrower system of blood vessels and probably also the larger quantity of blood, has a lower degree of nourishment for its effect.133 That, however, the larger skulls of larger persons, coupled with the quantitative changes occasioned by the size of the skull promote the vigor of the several sections of the brain is a matter that cannot be asserted.134

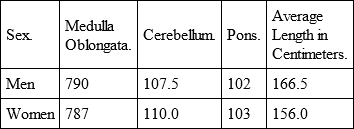

Of 107 mentally healthy men and 148 women of the ages of 20 to 59, the weight of the brain per thousand was:

The absolute and relative excess in the weight of the cerebellum of woman has an enormous significance. With animals that run immediately upon birth, the cerebellum is much more powerfully developed than with animals that are born blind, are helpless, and that learn to walk with difficulty. Accordingly, and in consequence of its connection with the cerebrum, subcortical center and the spinal cord, the cerebellum is a station of the muscular and of the chief nervous system, by means of both of which qualities we keep our equilibrium. The more massive cerebellum with woman, together with the comparative shortness and tenderness of her bones, explains her comparative quickness and easiness of motion, her quicker and higher co-ordination of the muscles for their functions, and her knack of quickly sizing up a situation, and finding her way in the midst of a confusion of associations. Woman is furthermore aided in the latter faculty through the greater excitability of her cerebral cortex. Meynert says: —

1. All structural anomalies associated with anaemia of the blood – including also a small heart and narrow arteries – should be considered as subject structural defects. Upon this depends not only the ready exhaustibility of the cortex, but also the phenomena of irritability, named by Meynert, localized irritable weakness.

2. The branches of blood vessels, supplying the subcortical centers from the base, are short, thick, straight, palisade-like, while those on the surface of the brain, supplying the cortex, run in long tortuous lines. And it is because of that, since with the increased length of the blood vessels the resistance to the propulsive force of the heart is increased, that the subcortical centers, the moment fatigue supervenes, are better supplied with blood than the cortex, they are less readily fatigued than the more readily exhaustible cerebrum.

3. Because of this and because of the more watery character of woman's blood and great extent of subcortical centers in woman in comparison with cerebrum, the physical equilibrium of woman is more unstable than of man.

4. All nerves (except the optic and olfactory, which spread out directly in the cortex, save some of their filaments terminating in the subcortical centers) terminate in the subcortical center; the cortex of the cerebrum acts as a checking organ for the subcortical center; as the cerebral cortex in woman, as already stated, is at a disadvantage not only from the anatomical standpoint, but also in the quality of its blood supply, woman is not only more easily fatigued, but also more readily excitable (irritable, nervous).

These facts explain, on the one hand, what is called the superior endowment of woman, and, on the other, her inclination to sudden changes of opinion, as well as to hallucinations and illusions. This state of unstable equilibrium between the dura mater and the pons becomes particularly normal during menstruation, pregnancy, lying-in, and at her climacteric. As a result of her physical organization, woman is more inclined to melancholy than man, and likewise is the inclination to mental derangement stronger with her; on the other hand, the male sex excels her in the number of cases of megalomania.

Such, in substance, is the information furnished us by the authority whom we have been quoting.

As a matter of course, in so far as the cited differences depend upon the nature of the sex-distinctions, they can not be changed; in how far these differences in the make-up of the blood and the brain may be modified by a change of life (nourishment, mental and physical gymnastics, occupation, etc.) is a matter that, for the present, lies beyond all accurate calculation. But this seems certain: modern woman differs more markedly from man than primitive woman, or than the women of backward peoples, and the circumstance is easily explained by the social development that the last 1,000 or 1,500 years forced upon woman among the nations of civilization.

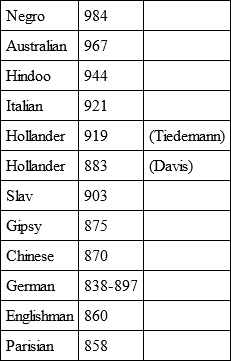

According to Lombroso and Ferrero, the mean capacity of the female skull, the male skull being assumed at 1,000, is as follows: —

The contradictory findings for Hollanders and Germans show that the measurements were made on very different quantitative and qualitative materials, and, consequently, are not absolutely reliable. One thing, however, is evident from the figures: Negro, Australian and Hindoo women have a considerably larger brain capacity than their German, English and Parisian sisters, and yet the latter are all more intelligent. The comparisons established in the weight of the brain of deceased men of note, reveal similar contradictions and peculiarities. According to Prof. Reclam, the brain of the naturalist Cuvier weighed 1,861 grams, of Byron 1,807, of the mathematician Dirichlet 1,520, of the celebrated mathematician Gauss 1,492, of the philologist Hermann 1,358, of the scientist Hausmann 1,226. The last of these had a brain below the average weight of that of women, which, according to Bischoff, weighs 1,250 grams. But a special irony of fate wills it that the brain of Prof. Bischoff himself, who died a few years ago in St. Petersburg, weighed only 1,245 grams, and Bischoff it was who most obstinately grounded his claim of woman's inferiority on the fact that woman, on the average, had 100 grams less brain than man. The brain of Gambetta also weighed considerably below the average female brain, it weighed only 1,180 grams, and Dante, too, is said to have had a brain below the average weight for men. Figures of the same sort are found in Dr. Havelock Ellis' work. According thereto, an every day person, whose brain Bischoff weighed, had 2,222 grams; the poet Turgeniew 2,012; while the third heaviest brain on the list belonged to an idiot of the duchy of Hants. The brain of a common workingman, also examined by Bischoff, weighed 1,925 grams. The heaviest woman's brains weighed 1,742 and 1,580 grams, two of which were of insane women.

The conclusion is, accordingly, justified that as little as size of body justifies inferences as to strength of body, so little does the weight of the brain-mass warrant inferences as to mental powers. There are very small animals (ants, bees) that, in point of intelligence, greatly excel much larger ones (sheep, cows), just as men of large body are often found far behind others of smaller or unimposing stature. Accordingly, the important factor is not merely the quantity of brain matter, but more especially the brain organization, and, not least of all, the exercise and use of the brain power.