полная версия

полная версияThe Golden Butterfly

5. This is a country where people read a great deal. More books are printed in England than in any other country in the world. Reading forms the amusement of half our hours, the delight of our leisure time. For the whole of its reading Society agrees to pay Mundie & Smith from three to ten guineas a house. Here is a sum in arithmetic: house-bills, £1,500 a year; wine-bill, £300; horses, £500; rent, £400; travelling, £400; dress – Lord knows what; reading – say £5; also, spent at Smith's stalls in two-shilling novels, say thirty shillings. That is the patronage of Literature. Successful authors make a few hundreds a year – successful grocers make a few thousands – and people say, "How well is Literature rewarded!"

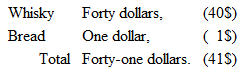

Mr. Gilead Beck once told me of a party gathered together in Virginia City to mourn the decease of a dear friend cut off prematurely. The gentleman intrusted with the conduct of the evening's entertainment had one-and-forty dollars put into his hands to be laid out to the best advantage. He expended it as follows: —

"What, in thunder," asked the chairman, "made you waste all that money in bread?"

Note. – He had never read Henry IV.

The modern patronage of Literature is exactly like the proportion of bread observed by the gentleman of Virginia City.

Five pounds a year for the mental food of all the household.

Enough; social reform is a troublesome and an expensive thing. Let it be done by the societies; there are plenty of people anxious to be seen on platforms, and plenty of men who are rejoiced to take the salary of secretary.

Think again of Mr. Gilead Beck's Luck and what it meant. The wildest flights of your fancy never reach to a fourth part of his income. The yearly revenues of a Grosvenor fall far short of this amazing good fortune, Out of the bowels of the earth was flowing for him a continuous stream of wealth that seemed inexhaustible. Not one well, but fifty, were his, and all yielding. When he told Jack Dunquerque that his income was a thousand pounds a day, he was far within the limit. In these weeks he was clearing fifteen hundred pounds in every twenty-four hours. That makes forty-five thousand pounds a month; five hundred and forty thousand pounds a year. Can a Grosvenor or a Dudley reach to that?

The first well was still the best, and it showed no signs of giving out; and as Mr. Beck attributed its finding to the direct personal instigation of the Golden Butterfly, he firmly believed that it never would give out. Other shafts had been sunk round it, but with varying success; the ground covered with derricks and machinery erected for boring fresh wells and working the old, an army of men were engaged in these operations; a new town had sprung up in the place of Limerick City; and Gilead P. Beck, its King, was in London, trying to learn how his money might best be spent.

It weighed heavily upon his mind; the fact that he was by no effort of his own, through no merit of his own, earning a small fortune every week made him thoughtful. In his rough way he took the wealth as so much trust-money. He was entitled, he thought, to live upon it according to his inclination; he was to have what his soul craved for he was to use it first for his own purposes; but he was to devote what he could not spend – that is, the great bulk of it – somehow to the general good. Such was the will of the Golden Butterfly.

I do not know how the idea came into Gilead Beck's head that he was to regard himself a trustee. The man's antecedents would seem against such a conception of Fortune and her responsibilities. Born in a New England village, educated till the age of twelve in a village school, he had been turned upon the world to make his livelihood in it as best he could. He was everything by turns; there was hardly a trade that he did not attempt, not a calling which he did not for a while follow. Ill luck attended him for thirty years; yet his courage did not flag. Every fresh attempt to escape from poverty only seemed to throw him back deeper in the slough. Yet he never despaired. His time would surely come. He preserved his independence of soul, and he preserved his hope.

But all the time he longed for wealth. The desire for riches is an instinct with the Englishman, a despairing dream with the German, a stimulus for hoarding with the Frenchman, but it is a consuming fire with the American. Gilead P. Beck breathed an atmosphere charged with the contagion of restless ambition. How many great men – presidents, vice-presidents, judges, orators, merchants – have sprung from the obscure villages of the older States? Gilead Beck started on his career with a vague idea that he was going to be something great. As the years went on he retained the belief, but it ceased to take a concrete form. He did not see himself in the chair of Ulysses Grant; he did not dream of becoming a statesman or an orator But he was going to be a man of mark. Somehow he was bound to be great.

And then came the Golden Butterfly.

See Mr. Beck now. It is ten in the morning. He has left the pile of letters, most of them begging letters, unopened opened at his elbow. He has got the case of glass and gold containing the Butterfly on the table. The sunlight pouring in at the opened window strikes upon the yellow metal, and lights up the delicately chased wings of this freak of Nature. Poised on the wire, the Golden Butterfly seems to hover of its own accord upon the petals of the rose. It is alive. As its owner sits before it, the creature seems endowed with life and motion. This is nonsense, but Mr. Beck thinks so at the moment.

On the table is a map of his Canadian oil-fields.

He sits like this nearly every morning, the gilded box before him. It is his way of consulting the oracle. After his interview with the Butterfly he rises refreshed and clear of vision. This morning, if his thoughts could be written down, they might take this form:

"I am rich beyond the dreams of avarice. I have more than I can spend upon the indulgence of every whim that ever entered the head of sane man. When I have bought all the luxuries that the world has to sell, there still remains to be saved more than any other living man has to spend.

"What am I to do with it?

"Shall I lay it up in the Bank? The Bank might break. That is possible. Or the well might stop. No; that is impossible. Other wells have stopped, but no well has run like mine, or will again; for I have struck through the crust of the earth into the almighty reservoir.

"How to work out this trust? Who will help me to spend the money aright? How is such a mighty pile to be spent?

"Even if the Butterfly were to fall and break, who can deprive me of my wealth?"

His servant threw open the door: "Mr. Cassilis, sir."

CHAPTER XVIII

"Doubtfully it stood,As two spent swimmers that do cling togetherAnd choke their art."One of Gilead Beck's difficulties – perhaps his greatest – was his want of an adviser. People in England who have large incomes pay private secretaries to advise them. The post is onerous, but carries with it considerable influence. To be a Great Man's whisperer is a position coveted by many. At present the only confidential adviser of the American Cræsus was Jack Dunquerque, and he was unsalaried and therefore careless. Ladds and Colquhoun were less ready to listen, and Gabriel Cassilis showed a want of sympathy with Mr. Beck's Trusteeship which was disheartening. As for Jack, he treated the sacred Voice, which was to Gilead Beck what his demon was to Socrates, with profound contempt. But he enjoyed the prospect of boundless spending in which he was likely to have a disinterested share. Next to unlimited "chucking" of his own money, the youthful Englishman would like – what he never gets – the unlimited chucking of other people's. So Jack brought ideas, and communicated them as they occurred.

"Here is one," he said. "It will get rid of thousands; it will be a Blessing and a Boon for you; it will make a real hole in the Pile; and it's Philanthropy itself. Start a new daily."

Mr. Beck was looking straight before him with his hands in his pockets. His face was clouded with the anxiety of his wealth. Who would wish to be a rich man?

"I have been already thinking of it, Mr. Dunquerque," he said. "Let us talk it over."

He sat down in his largest easy-chair, and chewed the end of an unlighted cigar.

"I have thought of it," he went on. "I want a paper that shall have no advertisements and no leading articles. If a man can't say what he wants to say in half a column, that man may go to some other paper. I shall get only live men to write for me. I will have no long reports of speeches, and the bunkum of life shall be cut out of the paper."

"Then it will be a very little paper."

"No, sir. There is a great deal to say, once you get the right man to say it. I've been an editor myself, and I know."

"You will not expect the paper to pay you?"

"No, sir; I shall pay for that paper. And there shall be no cutting up of bad books to show smart writing. I shall teach some of your reviews good manners."

"But we pride ourselves on the tone of our reviews."

"Perhaps you do, sir. I have remarked, that Englishmen pride themselves on a good many things. I will back a first-class British subject for bubbling around against all humanity. See, Mr. Dunquerque, last week I read one of your high-toned reviews. There was an article in it on a novel. The novel was a young lady's novel. When I was editing the Clearville Roarer I couldn't have laid it on in finer style for the rough back of a Ward Politician. And a young lady!"

"People like it, I suppose," said Jack.

"I dare say they do, sir. They used to like to see a woman flogged at the cart-tail. I am not much of a company man, Mr. Dunquerque, but I believe that when a young lady sings out of tune it is not considered good manners to get up and say so. And it isn't thought polite to snigger and grin. And in my country, if a man was to invite the company to make game of that young lady he would perhaps be requested to take a header through the window. Let things alone, and presently that young lady discovers that she is not likely to get cracked up as a vocaller. I shall conduct my paper on the same polite principles. If a man thinks he can sing and can't sing, let him be for a bit. Perhaps he will find out his mistake. If he doesn't, tell him gently. And if that won't do, get your liveliest writer to lay it on once for all. But to go sneakin' and pryin' around, pickin' out the poor trash, and cutting it up to make the people grin – it's mean, Mr. Dunquerque, it's mean. The cart-tail and the cat-o'-nine was no worse than this exhibition. I'm told it's done regularly, and paid for handsomely."

"Shall you be your own editor?"

"I don't know, sir. Perhaps if I stay long enough in this city to get to the core of things, I shall scatter my own observations around. But that's uncertain."

He rose slowly – it took him a long time to rise – and extended his long arms, bringing them together in a comprehensive way, as if he was embracing the universe.

"I shall have central offices in New York and London. But I shall drive the English team first. I shall have correspondents all over the world, and I shall have information of every dodge goin,' from an emperor's ambition to a tin-pot company bubble."

He brought his fingers together with a clasp. Jack noticed how strong and bony those fingers were, with hands whose muscles seemed of steel.

The countenance of the man was earnest and solemn. Suddenly it changed expression, and that curious smile of his, unlike the smile of any other man, crossed his face.

"Did I ever tell you my press experiences?" he asked. "Let us have some champagne, and you shall hear them."

The champagne having been brought he told his story, walking slowly up and down with his hands in his pockets, and jerking out the sentences as if he was feeling for the most telling way of putting them.

Mr. Gilead Beck had two distinct styles of conversation. Generally, but for his American tone, the length of his sentences, and a certain florid wealth of illustration, you might take him for an Englishman of eccentric habits of thought. When he went back to his old experiences he employed the vernacular – rich, metaphoric, and full – which belongs to the Western States in the rougher period of their development. And this he used now.

"I was in Chicago. Fifteen years ago. I wanted employment. Nobody wanted me. I spent most of the dollars, and thought I had better dig out for a new location, when I met one day an old schoolfellow named Rayner. He told me he was part proprietor of a morning paper. I asked him to take me on. He said he was only publisher, but he would take me to see the Editor, Mr. John B. Van Cott, and perhaps he would set me grinding at the locals. We found the Editor. He was a short active man of fifty, and he looked as cute as he was. Because, you see, Mr. Dunquerque, unless you are pretty sharp on a Western paper, you won't earn your mush. He was keeled back, I remember, in a strong chair, with his feet on the front of the table, and a clip full of paper on his knee. And in this position he used to write his leading articles. Squelchers, some of them; made gentlemen of opposite politics cry, and drove rival editors to polishing shooting-irons. The floor was covered with exchanges. And there was nothing else in the place but a cracked stove, half a dozen chairs standing around loose, and a spittoon.

"I mention these facts, Mr. Dunquerque, to show that there was good standing-room for a free fight of not more than two.

"Mr. Van Cott shook hands, and passed me the tobacco pouch, while Rayner chanted my praises. When he wound up and went away, the Editor began.

"'Wal, sir,' he said, 'you look as if you knew enough to go indoors when it rains, and Rayner seems powerful anxious to get you on the paper. A good fellow is Rayner; as white a man as I ever knew; and he has as many old friends as would make a good-sized city. He brings them all here, Mr. Beck, and wants to put every one on the paper. To hear him hold forth would make a camp-meeting exhorter feel small. But he's disinterested, is Rayner. It's all pure goodness.'

"I tried to feel as if I wasn't down-hearted. But I was.

"'Any way,' I said, 'if I can't get on here, I must dig out for a place nearer sundown. Once let me get a fair chance on a paper, and I can keep my end of the stick.'

"The Editor went on to tell me what I knew already, that they wanted live men on the paper, fellows that would do a murder right up to the handle. Then he came to business; offered me a triple execution just to show my style; and got up to introduce me to the other boys.

"Just then there was a knock at the door.

"'That's Poulter, our local Editor,' he said. 'Come in, Poulter. He will take you down for me.'

"The door opened, but it wasn't Poulter. I knew that by instinct. It was a rough-looking customer, with a black-dyed moustache, a diamond pin in his shirt front, and a great gold chain across his vest; and he carried a heavy stick in his hand.

"'Which is the one of you two that runs this machine?' he asked, looking from one to the other.

"'I am the Editor,' said Mr. Van Cott, 'if you mean that.'

"'Then you air the Rooster I'm after,' he went on. 'I am John Halkett of Tenth Ward. I want to know what in thunder you mean by printing infernal lies about me and my party in your miserable one-hoss paper.'

"He drew a copy of the paper from his pocket, and held it before the Editor's eyes.

"'You know your remedy, sir,' said Mr. Van Cott, quietly edging in the direction of the table, where there was a drawer.

"'That's what I do know. That's what I'm here for. There's two remedies. One is that you retract all the lies you have printed, the other' —

"'You need not tell me what the other is, Mr. Halkett.' As he spoke he drew open the drawer; but he hadn't time to take the pistol from it when the ward politician sprang upon him, and in a flash of lightning they were rolling over each other among the exchanges on the floor.

"If they had been evenly matched, I should have stood around to see fair. But it wasn't equal. Van Cott, you could see at first snap, was grit all through, and as full of fight as a game-rooster. But it was bulldog and terrier. So I hitched on to the stranger, and pulled him off by main force.

"'You will allow me, Mr. Van Cott,' I said, 'to take this contract off your hands. Choose a back seat sir, and see fair.'

"'Sail in,' cried Mr. Halkett, as cheerful as a coot, 'and send for the coroner, because he'll be wanted. I don't care which it is.'

"That was the toughest job I ever had. The strength of ward politicians' opinions lies in their powers of bruising, and John Halkett, as I learned afterwards, could light his weight in wild cats. Fortunately I was no slouch in those days.

"He met my advances halfway. In ten minutes you couldn't tell Halkett from me, nor me from Halkett. The furniture moved around cheerfully, and there was a lovely racket. The sub-editors, printers, and reporters came running in. It was a new scene for them, poor fellows, and they enjoyed it accordingly. The Editor they had often watched in a fight before, but here were two strangers worrying each other on the floor, with Mr. Van Cott out of it himself, dodging around cheering us on. That gave novelty.

"The sharpest of the reporters had his flimsy up in a minute, and took notes of the proceedings.

"We fought that worry through. It lasted fifteen minutes. We fought out of the office; we fought down the stairs; and we fought on the pavement.

"When it was over, I found myself arrayed in the tattered remnants of my grey coat, and nothing else. John Halkett hadn't so much as that. He was bruised and bleeding, and he was deeply moved. Tears stood in his eyes as he grasped me by the hand.

"'Stranger,' he said, 'will you tell me where you hail from?'

"'Air you satisfied, Mr. Halkett,' I replied, 'with the editorial management of this newspaper?'

"'I am,' he answered. 'You bet. This is the very best edited paper that ever ran. Good morning, sir. You have took the starch out of John Halkett in a way that no starch ever was took out of that man before. And if ever you get into a tight place, you come to me.'

"They put him in a cab, and sent him home for repairs. I went back to the Editor's room. He was going on again with his usual occupation of manufacturing squelchers. The fragments of the chairs lay around him, but he wrote on unmoved.

"'Consider yourself permanently engaged,' he said. 'The firm will pay for a new suit of clothes. Why couldn't you say at once that you were fond of fighting? I never saw a visitor tackled in a more lovable style. Why, you must have been brought up to it. And just to think that one might never have discovered your points if it hadn't been for the fortunate accident of John Halkett's call!'

"I said I was too modest to mention my tastes.

"'Most fortunate it is. Blevins, who used to do our fighting – a whole team he was at it – was killed three months ago on this very floor; there's the mark of his fluid still on the wall. We gave Blevins a first-class funeral, and ordered a two-hundred-dollar monument to commemorate his virtues. We were not ungrateful to Blevins.

"'Birkett came next,' he went on, making corrections with a pencil stump. 'But he was licked like a cur three times in a fortnight. People used to step in on purpose to wallop Birkett, it was such an easy amusement. The paper was falling into disgrace, so we shunted him. He drives a cab now, which suits him better, because he was always gentlemanly in his ways.

"'Carter, who followed, was very good in some respects, but he wanted judgment. He's in hospital with a bullet in the shoulder, which comes of his own carelessness. We can't take him on again any more, even if he was our style, which he never was.'

"'And who does the work now?' I ventured to ask.

"'We have had no regular man since Carter was carried off on a shutter. Each one does a little, just as it happens to turn up. But I don't like the irregular system. It's quite unprofessional.'

"I asked if there was much of that sort of thing.

"'Depends on the time of year. It is the dull season just now, but we are lively enough when the fall elections come on. We sometimes have a couple a day then. You won't find yourself rusting. And if you want work, we can stir up a few editors by judicious writing. I'm powerful glad we made your acquaintance, Mr. Beck.'

"That, Mr. Dunquerque, is how I became connected with the press."

"And did you like the position?"

"It had its good points. It was a situation of great responsibility. People were continually turning up who disliked our method of depicting character, and so the credit of the paper mainly rested on my shoulders. No, sir; I got to like it, except when I had to go into hospital for repairs. And even that had its charms, for I went there so often that it became a sort of home, and the surgeons and nurses were like brothers and sisters."

"But you gave up the post?" said Jack.

"Well, sir, I did. The occupation, after all, wasn't healthy, and was a little too lively. The staff took a pride in me too, and delighted to promote freedom of discussion. If things grew dull for a week or two, they would scarify some ward ruffian just to bring on a fight. They would hang around there to see that ward ruffian approach the office, and they would struggle who should be the man to point me out as the gentleman he wished to interview. They were fond of me to such an extent that they could not bear to see a week pass without a fight. And I will say this of them, that they were as level a lot of boys as ever destroyed a man's character.

"Most of the business was easy. They came to see Mr. Van Cott, and they were shown up to me. What there is of me, takes up a good deal of the room. And when they'd put their case I used to open the door and point. 'Git,' I would say. 'You bet,' was the general reply; and they would go away quite satisfied with the Editorial reception. But one a week or so there would be a put-up thing, and I knew by the look of my men which would take their persuasion fighting.

"It gradually became clear to me that if I remained much longer there would be a first class funeral, with me taking a prominent part in the procesh; and I began to think of digging out while I still had my hair on.

"One morning I read an advertisement of a paper to be sold. It was in the city of Clearville, Illinois, and it seemed to suit. I resolved to go and look at it, and apprised Mr. Van Cott of my intention.

"'I'm powerful sorry,' he said; 'but of course we can't keep you if you will go. You've hoed your row like a square man ever since you came, and I had hoped to have your valuable services till the end.'

"I attempted to thank him, but he held up his hand, and went on thoughtfully.

"'There's room in our plat at Rose Hill Cemetery for one or two more; and I had made up my mind to let you have one side of the monument all to yourself. The sunny side, too – quite the nicest nest in the plat. And we'd have given you eight lines of poetry – Blevins only got four, and none of the other fellows any. I assure you, Beck, though you may not think it, I have often turned this over in my mind when you have been in hospital, and I got to look on it as a settled thing. And now this is how it ends. Life is made up of disappointments.'

"I said it was very good of him to take such an interest in my funeral, but that I had no yearning at present for Rose Hill Cemetery, and I thought it would be a pity to disturb Blevins. As I had never known him and the other boys, they mightn't be pleased if a total stranger were sent to join their little circle.

"Mr. Van Cott was good enough to say that they wouldn't mind it for the sake of the paper: but I had my prejudices, and I resigned.

"I don't know whether you visited Illinois when you were in America, Mr. Dunquerque; but if you did, perhaps you went to Clearville. It is in that part of the State which goes by the name of Egypt, and is so named on account of the benighted condition of the natives. It wasn't a lively place to go to, but still —