полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 1: Frontiersman, soldier, lawmaker, 1755-1788

"Such speeches within these walls, from a character so venerable and estimable," declared Lee, "easily progress into overt acts, among the less thinking and the vicious." Lee implored that the "God of heaven avert from my country the dreadful curse!" But, he thundered, "if the madness of some and the vice of others" should arouse popular resistance to the Constitution, the friends of that instrument "will meet the afflicting call"; and he plainly intimated that any uprising of the people against the proposed National Government would be met with arms.1328 The guns of Sumter were being forged.

On the night of June 23, the Constitutionalists decided to deliver their final assault. They knew that it must be a decisive one. The time had arrived for the meeting of the Legislature which was hostile to the Constitution;1329 and if the friends of the proposed new Government were to win at all, they must win quickly. A careful poll had shown them that straight-out ratification without amendment of some kind was impossible. So they followed the plan of the Massachusetts Constitutionalists and determined to offer amendments themselves – but amendments merely by way of recommendation and subsequent to ratification, instead of previous amendments as a condition of ratification. The venerable Wythe was chosen to carry out the programme. On Tuesday morning, June 24, Pendleton called to the chair Thomas Mathews, one of the best parliamentarians in the Convention, a stanch Constitutionalist, a veteran of the Revolution, and a popular man.

Instantly Mathews recognized Wythe; for Henry was ready with his amendments, and, had an Anti-Constitutionalist been in the chair, would have been able to offer them before Wythe could move for ratification. Wythe, pale and fatigued, was so agitated that at first he could not speak plainly.1330 After reviewing the whole subject, he said that to insist on previous amendments might dissolve the Union, whereas all necessary amendments could easily be had after ratification. Wythe then moved the Constitutionalists' resolution for ratification.

In a towering rage, Henry rose for what, outside of the courtroom, was the last great speech of his life.1331 He felt that he had been unjustly forestalled and that the battle against the Constitution was failing because of the stern and unfair tactics of his foes.1332 The Constitutionalists admitted, said Henry, that the Constitution was "capitally defective"; yet they proposed to ratify it without first remedying its conceded faults. This was so absurd that he was "sure the gentleman [Wythe] meant nothing but to amuse the committee. I know his candor," said Henry. "His proposal is an idea dreadful to me… The great body of yeomanry are in decided opposition" to the Constitution.

Henry declared that of his own personal knowledge "nine tenths of the people" in "nineteen counties adjacent to each other" were against the proposed new National Government. The Constitutionalists' plan of "subsequent amendments will not do for men of this cast." And how do the people feel even in the States that had ratified it? Look at Pennsylvania! Only ten thousand out of seventy thousand of her people were represented in the Pennsylvania Convention.

If the Constitution was ratified without previous amendments, Henry declared that he would "have nothing to do with it." He offered the Bill of Rights and amendments which he himself had drawn, proposing to refer them to the other States "for their consideration, previous to its [Constitution's] ratification."1333 Henry then turned upon the Constitutionalists their own point by declaring that it was their plan of ratification without previous amendments which would endanger the Union.1334 Randolph followed briefly and Dawson at great length. Madison for the Constitutionalists, and Grayson for the opposition, exerted themselves to the utmost. Nature aided Henry when he closed the day in an appeal such as only the supremely gifted can make.

"I see," cried Henry, in rapt exaltation, "the awful immensity of the dangers with which it [the Constitution] is pregnant. I see it. I feel it. I see beings of a higher order anxious concerning our decision. When I see beyond the horizon that bounds human eyes, and look at the final consummation of all human things, and see those intelligent beings which inhabit the ethereal mansions reviewing the political decisions and revolutions which, in the progress of time, will happen in America, and the consequent happiness or misery of mankind, I am led to believe that much of the account, on one side or the other, will depend on what we now decide. Our own happiness alone is not affected by the event. All nations are interested in the determination. We have it in our power to secure the happiness of one half of the human race. Its adoption may involve the misery of the other hemisphere."1335

In the midst of this trance-like spell which the master conjurer had thrown over his hearers, a terrible storm suddenly arose. Darkness fell upon the full light of day. Lightnings flashed and crashing thunders shook the Convention hall. With the inspiration of genius this unrivaled actor made the tempest seem a part of his own denunciation. The scene became insupportable. Members rushed from their seats.1336 As Henry closed, the tempest died away.

The spectators returned, the members recovered their composure, and the session was resumed.1337 Nicholas coldly moved that the question be put at nine o'clock on the following morning. Clay and Ronald opposed, the latter declaring that without such amendments "as will secure the happiness of the people" he would "though much against his inclination vote against this Constitution."

Anxious and prolonged were the conferences of the Constitutionalist managers that night. The Legislature had convened. It was now or never for the friends of the Constitution. The delay of a single day might lose them the contest. That night and the next morning they brought to bear every ounce of their strength. The Convention met for its final session on the historic 25th of June, with the Constitutionalists in gravest apprehension. They were not sure that Henry would not carry out his threat to leave the hall; and they pictured to themselves the dreaded spectacle of that popular leader walking out at the head of the enraged opposition.1338

Into the hands of the burly Nicholas the Constitutionalists wisely gave command. The moment the Convention was called to order, the chair recognized Nicholas, who acted instantly with his characteristically icy and merciless decision. "The friends of the Constitution," said Nicholas, "wish to take up no more time, the matter being now fully discussed. They are convinced that further time will answer no end but to serve the cause of those who wish to destroy the Constitution. We wish it to be ratified and such amendments as may be thought necessary to be subsequently considered by a committee in order to be recommended to Congress." Where, he defiantly asked, did the opposition get authority to say that the Constitutionalists would not insist upon amendments after they had secured ratification of the Constitution? They really wished for Wythe's amendments;1339 and would "agree to any others which" would "not destroy the spirit of the Constitution." Nicholas moved the reading of Wythe's resolution in order that a vote might be taken upon it.1340

Tyler moved the reading of Henry's proposed amendments and Bill of Bights. Benjamin Harrison protested against the Constitutionalists' plan. He was for previous amendment, and thought Wythe's "measure of adoption to be unwarrantable, precipitate, and dangerously impolitic." Madison reassured those who were fearful that the Constitutionalists, if they won on ratification, would not further urge the amendments Wythe had offered; the Constitutionalists then closed, as they had begun, with admirable strategy.

James Innes was Attorney-General. His duties had kept him frequently from the Convention. He was well educated, extremely popular, and had been one of the most gifted and gallant officers that Virginia had sent to the front during the Revolution. Physically he was a colossus, the largest man in that State of giants. Such was the popular and imposing champion which the Constitutionalists had so well chosen to utter their parting word.1341 And Innes did his utmost in the hardest of situations; for if he took too much time, he would endanger his own cause; if he did not make a deep impression, he would fail in the purpose for which he was put forward.1342

Men who heard Innes testify that "he spoke like one inspired."1343 For the opposition the learned and accomplished Tyler closed the general debate. It was time wasted on both sides. But that nothing might be left undone, the Constitutionalists now brought into action a rough, forthright member from the Valley. Zachariah Johnson spoke for "those who live in large, remote, back counties." He dwelt, he said, "among the poor people." The most that he could claim for himself was "to be of the middle rank." He had "a numerous offspring" and he was willing to trust their future to the Constitution.1344

Henry could not restrain himself; but he would better not have spoken, for he admitted defeat. The anxious Constitutionalists must have breathed a sigh of relief when Henry said that he would not leave the hall. Though "overpowered in a good cause, yet I will be a peaceable citizen." All he would try to do would be "to remove the defects of that system [the Constitution] in a constitutional way." And so, declared the scarred veteran as he yielded his sword to the victors, he would "patiently wait in expectation of seeing that government changed, so as to be compatible with the safety, liberty, and happiness, of the people."

Wythe's resolution of ratification now came to a vote. No more carefully worded paper for the purposes it was intended to accomplish ever was laid before a deliberative body. It reassured those who feared the Constitution, in language which went far to grant most of their demands; and while the resolve called for ratification, yet, "in order to relieve the apprehensions of those who may be solicitous for amendments," it provided that all necessary amendments be recommended to Congress. Thus did the Constitutionalists, who had exhausted all the resources of management, debate, and personal persuasion, now find it necessary to resort to the most delicate tact.

The opposition moved to substitute for the ratification resolution one of their own, which declared "that previous to the ratification … a declaration of rights … together with amendments … should be referred by this Convention to the other states … for their consideration." On this, the first test vote of the struggle, the Constitutionalists won by the slender majority of 8 out of a total of 168. On the main question which followed, the Anti-Constitutionalists lost but one vote and the Constitution escaped defeat by a majority of only 10.

To secure ratification, eight members of the Convention voted against the wishes of their constituents,1345 and two ignored their instructions.1346 Grayson openly but respectfully stated on the floor that the vote was the result of Washington's influence. "I think," said he, "that, were it not for one great character in America, so many men would not be for this government."1347 Followers of their old commander as the members from the Valley were, the fear of the Indians had quite as much to do with getting their support for a stronger National Government as had the weight of Washington's influence.1348

Randolph "humbly supplicated one parting word" before the last vote was taken. It was a word of excuse and self-justification. His vote, he said, would be "ascribed by malice to motives unknown to his breast." He would "ask the mercy of God for every other act of his life," but for this he requested only Heaven's justice. He still objected to the Constitution, but the ratification of it by eight States had now "reduced our deliberations to the single question of Union or no Union."1349 So closed the greatest debate ever held over the Constitution and one of the ablest parliamentary contests of history.

A committee was appointed to report "a form of ratification pursuant to the first resolution"; and another was selected "to prepare and report such amendments as by them shall be deemed necessary."1350 Marshall was chosen as a member of both these important committees.

The lengths to which the Constitutionalists were driven in order to secure ratification are measured by the amendments they were forced to bring in. These numbered twenty, in addition to a Bill of Rights, which also had twenty articles. The ten amendments afterwards made to the Constitution were hardly a shadow of those recommended by the Virginia Convention of 1788.

That body actually proposed that National excise or direct tax laws should not operate in any State, in case the State itself should collect its quota under State laws and through State officials; that two thirds of both houses of Congress, present, should be necessary to pass navigation laws or laws regulating commerce; that no army or regular troops should be "raised or kept up in time of peace" without the consent of two thirds of both houses, present; that the power of Congress over the seat of the National Government should be confined to police and administrative regulation. The Judiciary amendment would have imprisoned the Supreme Court within limits so narrow as to render that tribunal almost powerless and would have absolutely prevented the establishment of inferior National Courts, except those of Admiralty.1351 Yet only on such terms could ratification be secured even by the small and uncertain majority that finally voted for it.

On June 25, Clinton's suppressed letter to Randolph was laid before the House of Delegates which had just convened.1352 Mason was so furious that he drew up resolutions for an investigation of Randolph's conduct.1353 But the deed was done, anger was unavailing, and the resolutions never were offered.1354

So frail was the Constitutionalist strength that if the news of the New Hampshire ratification had not reached Virginia, it is more than probable that Jefferson's advice would have been followed and that the Old Dominion would have held back until all the amendments desired by the opposition had been made a part of the fundamental law;1355 and the Constitution would have been a far different and infinitely weaker instrument than it is.

Burning with wrath, the Anti-Constitutionalists held a meeting on the night of the day of the vote for ratification, to consider measures for resisting the new National Government. The character of Patrick Henry never shone with greater luster than when he took the chair at this determined gathering of furious men. He had done his best against the Constitution, said Henry, but he had done it in the "proper place"; the question was settled now and he advised his colleagues that "as true and faithful republicans, they had all better go home!"1356 Well might Washington write that only "conciliatory conduct" got the Constitution through;1357 well might he declare that "it is nearly impossible for anybody who has not been on the spot (from any description) to conceive what the delicacy and danger of our situation have been."1358

And Marshall had been on the spot. Marshall had seen it all. Marshall had been a part of it all. From the first careful election programme of the Constitutionalists, the young Richmond lawyer had been in every meeting where the plans of the managers were laid and the order of battle arranged. No man in all the country knew better than he, the hair's breadth by which the ordinance of our National Government escaped strangulation at its very birth. No one in America better understood how carefully and yet how boldly Nationalism must be advanced if it were to grow stronger or even to survive.

It was plain to Marshall that the formal adoption of the Constitution did not end the battle. That conflict, indeed, was only beginning. The fight over ratification had been but the first phase of the struggle. We are now to behold the next stages of that great contest, each as dramatic as it was vital; and we shall observe how Marshall bore himself on every field of this mighty civil strife, note his development and mark his progress toward that supreme station for which events prepared him. We are to witness his efforts to uphold the National Government, not only with argument and political activity, but also with a readiness to draw the sword and employ military force. We shall look upon the mad scenes resulting in America from the terrific and bloody convulsion in Europe and measure the lasting effect the French Revolution produced upon the statesmen and people of the United States. In short, we are to survey a strange swirl of forces, economic and emotional, throwing to the surface now one "issue" and now another, all of them centering in the sovereign question of Nationalism or States' Rights.

END OF VOLUME IAPPENDIX

I

WILL OF THOMAS MARSHALL, "CARPENTER"

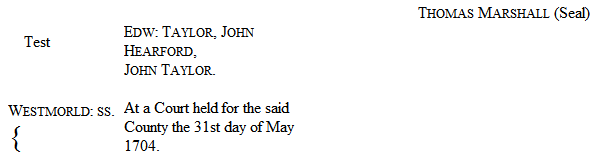

In the Name of God Amen! I, Thomas Marshall of the County of Westmoreland of Washington Parish, Carpenter, being very weak but of perfect memory thanks be to God for it doth ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form following, first I give and bequeath my soul into the hands of my blessed Creator & Redeemer hoping through meritts of my blessed Saviour to receive full pardon and remission of all my sins and my body to the Earth to be decently bur-yed according to the discretion of my Executrix which hereafter shall be named. Imps. I make and ordain my well beloved wife Martha Marshall to be my full and whole Executrix – Item, I will that my estate shall remain in the hands of my wife as long as she remain single but in case she marrys then she is to have her lawful part & the rest to be taken out of her hands equally to be divided among my children – Item, I will that if my wife marry, that David Brown Senr. and Jno. Brown to be guardians over my children and to take the estate in their hands bringing it to appraisement giving in good security to what it is valued and to pay my children their dues as they shall come to age. Item – I will that Elizabeth Rosser is to have a heifer delivered by my wife called White-Belly to be delivered as soon as I am deceast – Item, I will that my son William Marshall shall have my plantation as soon as he comes to age to him and his heirs forever, but in case that my son William die before he comes to age or die without issue then my plantation is to fall to the next heir apparent at law.

The last will and testament of Thomas Marshall within written was proved by the oaths of John Oxford and John Taylor two of the witnesses thereto subscribed and a Probat thereof granted to Martha Marshall his relict and Executrix therein named.

TestIa: Westcomb Cler. Com. Ped.Record aty: sexto die Juny:

1704. Pr.

Eundm Clerum.

A Copy. Teste:

Albert Stuart, Clerk.

By:

F. F. Chandler, Deputy Clerk.

[A Copy. Will of Thomas Marshall. Recorded in the Clerk's Office of the Circuit Court of Westmoreland County, in Deed and Will Book no. 3 at page 232 et seq.]

II

WILL OF JOHN MARSHALL "OF THE FOREST"

The last will and testament of John Marshall being very sick and weak but of perfect mind and memory is as followeth.

First of all I give and recommend my soul to God that gave it and my Body to the ground to be buried in a Christian like and Discent manner at the Discretion of my Executors hereafter mentioned? Item I give and bequeath unto my beloved daughter Sarah Lovell one negro girl named Rachel now in possession of Robert Lovell. Item I give and bequeath unto my beloved daughter Ann Smith one negro boy named Danniel now in possession of Augustine Smith. Item I give and bequeath unto my beloved daughter Lize Smith one negro boy named Will now in possession of John Smith. Item I give and bequeath unto my well beloved wife Elizabeth Marshall one negro fellow named Joe and one negro woman named Cate and one negro woman named pen after Delivering the first child next born of her Body unto my son John until which time she shall remain in the possession of my wife Likewise I leave my Corn and meat to remain unappraised for the use of my wife and children also I give and bequeath unto my wife one Gray mair named beauty and side saddle also six hogs also I leave her the use of my land During her widowhood, and afterwards to fall to my son Thomas Marshall and his heirs forever. Item I leave my Tobacco to pay my Debts and if any be over for the clothing of my small children. Item I give and bequeath unto my well Beloved son Thomas Marshall one negro woman named hanno and one negroe child named Jacob? Item I give and bequeathe unto my well beloved son John Marshall one negroe fellow named George and one negroe child named Nan. Item. I give and bequeathe unto my beloved son Wm. Marshall one negro woman named Sall and one negro boy named Hanable to remain in the possession of his mother until he come to the age of twenty years. Item I give and Bequeath unto my Beloved son Abraham Marshall one negro boy named Jim and one negroe girl named bett to remain in the possession of his mother until he come to the age of twenty years. Item I give and Bequeath unto my Beloved daughter Mary Marshall one negro girl named Cate and negro boy Gus to remain in possession of her mother until she come to the age of Eighteen years or until marriage. Item, I give and Bequeath unto my beloved Daughter Peggy Marshall one negro boy named Joshua and one negro girl named Liz to remain in possession of her mother until she come to the age of Eighteen or until marriage! Item. I leave my personal Estate Except the legacies abovementioned to be equally Divided Between my wife and six children last above mentioned. Item I constitute and appoint my wife and my two sons Thos. Marshall and John Marshall Executors of this my last will & testament In witness hereof I have hereunto set my hand and fixed my seal this first day of April One thousand seven hundred and fifty two. Interlined before assigned.

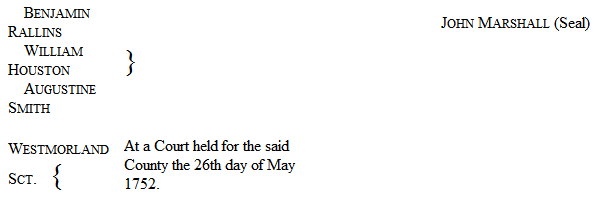

This Last will and testament of John Marshall decd. was presented into Court by Eliza. his relict and Thomas Marshall two of his Executors therein named who made oath thereto and being proved by the oaths of Benja. Rallings and Augustine Smith two of the witnesses thereto is admitted to record, and upon the motion of the said Eliza. & Thos. and their performing what the Law in such cases require Certificate is granted them for obtaining a probate thereof in due form.

TestGeorge Lee C. C. C. W.Recorded the 22d. day of June 1752.

Per

G. L. C. C. W. C.

A Copy. Teste:

Frank Stuart, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Westmoreland County, State of Virginia.

[A copy. John Marshall's Will. Recorded in the Clerk's Office of Westmoreland County, State of Virginia, in Deeds and Wills, no. 11, at page 419 et seq.]

III

DEED OF WILLIAM MARSHALL TO JOHN MARSHALL "OF THE FOREST"

This indenture made the 23d day of October in ye first year of ye reign of our sovereign Lord George ye 2d. by ye. grace of God of Great Brittain France & Ireland King defendr. of ye faith &c. and in ye year of our Lord God one thousand seven hundred & twenty seven, between William Marshall of ye. County of King & Queen in ye. Colony of Virginia planter of the one part & John Marshall of ye. County of Westmoreland Virginia of the other part: WITNESSETH that ye sd. William Marshall for and in consideration of ye. sum of five shillings sterling money of England to him in hand paid before ye sealing & delivery hereof ye. receipt whereof he doth hereby acknowledge & thereof & of every part thereof doth hereby acquit & discharge ye. sd John Marshall his heirs Exectrs & administrators by these presents, hath granted bargained & sold & doth hereby grant bargain & sell John Marshall his heirs Exectrs administrs & assigns all that tract or parsel of land (except ye parsel of land wch was sold out of it to Michael Hulburt) scitute lying & being in Westmoreland County in Washington parish on or near Appamattox Creek & being part of a tract of land containing 1200 acres formerly granted to Jno: Washington & Tho: Pope gents by Patent dated the 4th Septbr. 1661 & by them lost for want of seating & since granted to Collo. Nicholas Spencer by Ordr. Genll. Court dated Septbr. ye 21st 1668 & by ye said Spencer assign'd to ye. sd. Jno: Washington ye 9th of Octobr. 1669 which sd. two hundred acres was conveyed & sold to Thomas Marshall by Francis Wright & afterwards acknowledged in Court by John Wright ye. 28th day of May 1707 which sd two hundred acres of land be ye. same more or less and bounded as follows beginning at a black Oak standing in ye. southermost line of ye sd. 1200 acres & being a corner tree of a line that divideth this two hundred acres from One hundred acres of Michael Halbarts extending along ye. sd southermost lines west two hundred poles to a marked red Oak, thence north 160 poles to another marked red Oak thence east 200 poles to a black Oak of ye sd. Halberts to ye place it began, with all houses outhouses Orchards water water courses woods under woods timbers & all other things thereunto belonging with the revertion & revertions remainder & remainders rents issues & yearly profits & every part & parcell thereof. To have and to hold ye. sd. land & premises unto ye. sd John Marshall his heirs Executors Administrs & assignes from ye. day of ye date thereof for & during & untill the full end & term of six months from thence next ensuing fully to be compleat & ended to ye. end that by virtue thereof & of the statutes for transferring uses into possessions ye. sd John Marshall might be in actual possession of ye premises & might be enabled to take and accept of a grant release of the same to him ye. sd John Marshall his heires & assignes forever. In Witness whereof the parties to these present Indentures interchangeably have set – hands & seals ye. day & year first above written.