полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall, Volume 1: Frontiersman, soldier, lawmaker, 1755-1788

The better class of settlers who took up the "farms" abandoned by the first shunners of civilization, while a decided improvement, were, nevertheless, also improvident and dissipated. In a poor and slip-shod fashion, they ploughed the clearings which had now grown to fields, never fertilizing them and gathering but beggarly crops. Of these a part was always rye or corn, from which whiskey was made. The favorite occupation of this type was drinking to excess, arguing politics, denouncing government, and contracting debts.854 Not until debts and taxes had forced onward this second line of pioneer advance did the third appear with better notions of industry and order and less hatred of government and its obligations.855

In New England the out-push of the needy to make homes in the forests differed from the class just described only in that the settler remained on his clearing until it grew to a farm. After a few years his ground would be entirely cleared and by the aid of distant neighbors, cheered to their work by plenty of rum, he would build a larger house.856 But meanwhile there was little time for reading, small opportunity for information, scanty means of getting it; and mouth-to-mouth rumor was the settler's chief informant of what was happening in the outside world. In the part of Massachusetts west of the Connecticut Valley, at the time the Constitution was adopted, a rough and primitive people were scattered in lonesome families along the thick woods.857

In Virginia the contrast between the well-to-do and the masses of the people was still greater.858 The social and economic distinctions of colonial Virginia persisted in spite of the vociferousness of democracy which the Revolution had released. The small group of Virginia gentry were, as has been said, well educated, some of them highly so, instructed in the ways of the world, and distinguished in manners.859 Their houses were large; their table service was of plate; they kept their studs of racing and carriage horses.860 Sometimes, however, they displayed a grotesque luxury. The windows of the mansions, when broken, were occasionally replaced with rags; servants sometimes appeared in livery with silk stockings thrust into boots;861 and again dinner would be served by naked negroes.862

The second class of Virginia people were not so well educated, and the observer found them "rude, ferocious, and haughty; much attached to gaming and dissipation, particularly horse-racing and cock-fighting"; and yet, "hospitable, generous, and friendly." These people, although by nature of excellent minds, mingled in their characters some of the finest qualities of the first estate, and some of the worst habits of the lower social stratum. They "possessed elegant accomplishments and savage brutality."863 The third class of Virginia people were lazy, hard-drinking, and savage; yet kind and generous.864 "Whenever these people come to blows," Weld testifies, "they fight just like wild beasts, biting, kicking, and endeavoring to tear each other's eyes out with their nails"; and he says that men with eyes thus gouged out were a common sight.865

The generation between the birth of Marshall and the adoption of the Constitution had not modified the several strata of Virginia society except as to apparel and manners, both of which had become worse than in colonial times.

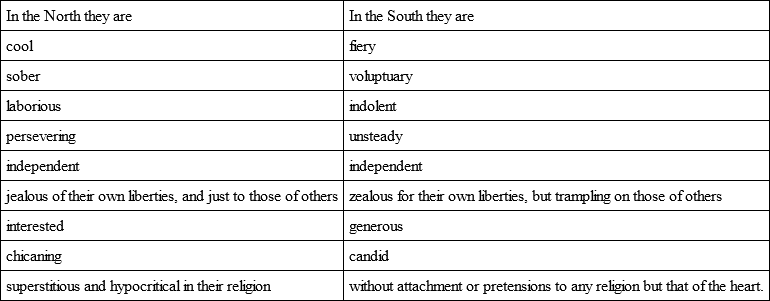

Schoepf found shiftlessness866 a common characteristic; and described the gentry as displaying the baronial qualities of haughtiness, vanity, and idleness.867 Jefferson divides the people into two sections as regards characteristics, which were not entirely creditable to either. But in his comparative estimate Jefferson is far harsher to the Southern population of that time than he is to the inhabitants of other States; and he emphasizes his discrimination by putting his summary in parallel columns.

"While I am on this subject," writes Jefferson to Chastellux, "I will give you my idea of the characters of the several States.

"These characteristics," continues Jefferson, "grow weaker and weaker by graduation from North to South and South to North, insomuch that an observing traveller, without the aid of the quadrant may always know his latitude by the character of the people among whom he finds himself."

"It is in Pennsylvania," Jefferson proceeds in his careful analysis, "that the two characters seem to meet and blend, and form a people free from the extremes both of vice and virtue. Peculiar circumstances have given to New York the character which climate would have given had she been placed on the South instead of the north side of Pennsylvania. Perhaps too other circumstances may have occasioned in Virginia a transplantation of a particular vice foreign to its climate." Jefferson finally concludes: "I think it for their good that the vices of their character should be pointed out to them that they may amend them; for a malady of either body or mind once known is half cured."868

A plantation house northwest of Richmond grumblingly admitted a lost traveler, who found his sleeping-room with "filthy beds, swarming with bugs" and cracks in the walls through which the sun shone.869 The most bizarre contrasts startled the observer – mean cabins, broken windows, no bread, and yet women clad in silk with plumes in their hair.870 Eight years after our present National Government was established, the food of the people living in the Shenandoah Valley was salt fish, pork, and greens; and the wayfarer could not get fresh meat except at Staunton or Lynchburg,871 notwithstanding the surrounding forests filled with game or the domestic animals which fed on the fields where the forests had been cleared away.

Most of the houses in which the majority of Virginians then lived were wretched;872 Jefferson tells us, speaking of the better class of dwellings, that "it is impossible to devise things more ugly, uncomfortable, and happily more perishable." "The poorest people," continues Jefferson, "build huts of logs, laid horizontally in pens, stopping the interstices with mud… The wealthy are attentive to the raising of vegetables, but very little so to fruits… The poorer people attend to neither, living principally on … animal diet."873

In general the population subsisted on worse fare than that of the inhabitants of the Valley.874 Even in that favored region, where religion and morals were more vital than elsewhere in the Commonwealth, each house had a peach brandy still of its own; and it was a man of notable abstemiousness who did not consume daily a large quantity of this spirit. "It is scarcely possible," writes Weld, "to meet with a man who does not begin the day with taking one, two, or more drams as soon as he rises."875

Indeed, at this period, heavy drinking appears to have been universal and continuous among all classes throughout the whole country876 quite as much as in Virginia. It was a habit that had come down from their forefathers and was so conspicuous, ever-present and peculiar, that every traveler through America, whether native or foreign, mentions it time and again. "The most common vice of the inferior class of the American people is drunkenness," writes La Rochefoucauld in 1797.877 And Washington eight years earlier denounced "drink which is the source of all evil – and the ruin of half the workmen in this country."878 Talleyrand, at a farmer's house in the heart of Connecticut, found the daily food to consist of "smoked fish, ham, potatoes, strong beer and brandy."879

Court-houses built in the center of a county and often standing entirely alone, without other buildings near them, nevertheless always had attached to them a shanty where liquor was sold.880 At country taverns which, with a few exceptions, were poor and sometimes vile,881 whiskey mixed with water was the common drink.882 About Germantown, Pennsylvania, workingmen received from employers a pint of rum each day as a part of their fare;883 and in good society men drank an astonishing number of "full bumpers" after dinner, where, already, they had imbibed generously.884 The incredible quantity of liquor, wine, and beer consumed everywhere and by all classes is the most striking and conspicuous feature of early American life. In addition to the very heavy domestic productions of spirits,885 there were imported in 1787, according to De Warville, four million gallons of rum, brandy, and other spirits; one million gallons of wine; three million gallons of molasses (principally for the manufacture of rum); as against only one hundred and twenty-five thousand pounds of tea.886

Everybody, it appears, was more interested in sport and spending than in work and saving. As in colonial days, the popular amusements continued to be horse-racing and cock-fighting; the first the peculiar diversion of the quality; the second that of the baser sort, although men of all conditions of society attended and delighted in both.887 But the horse-racing and the cock-fighting served the good purpose of bringing the people together; for these and the court days were the only occasions on which they met and exchanged views. The holding of court was an event never neglected by the people; but they assembled then to learn what gossip said and to drink together rather than separately, far more than they came to listen to the oracles from the bench or even the oratory at the bar; and seldom did the care-free company break up without fights, sometimes with the most serious results.888

Thus, scattered from Maine to Florida and from the Atlantic to the Alleghanies, with a skirmish line thrown forward almost to the Mississippi, these three and a quarter millions of men, women, and children, did not, for the most part, take kindly to government of any kind. Indeed, only a fraction of them had anything to do with government, for there were no more than seven hundred thousand adult males among them,889 and of these, in most States, only property-holders had the ballot. The great majority of the people seldom saw a letter or even a newspaper; and the best informed did not know what was going on in a neighboring State, although anxious for the information.

"Of the affairs of Georgia, I know as little as of those of Kamskatska," wrote Madison to Jefferson in 1786.890 But everybody did know that government meant law and regulation, order and mutual obligation, the fulfillment of contracts and the payment of debts. Above all, everybody knew that government meant taxes. And none of these things aroused what one would call frantic enthusiasm when brought home to the individual. Bloated and monstrous individualism grew out of the dank soil of these conditions. The social ideal had hardly begun to sprout; and nourishment for its feeble and languishing seed was sucked by its overgrown rival.

Community consciousness showed itself only in the more thickly peopled districts, and even there it was feeble. Generally speaking and aside from statesmen, merchants, and the veterans of the Revolution, the idea of a National Government had not penetrated the minds of the people. They managed to tolerate State Governments, because they always had lived under some such thing; but a National Government was too far away and fearsome, too alien and forbidding for them to view it with friendliness or understanding. The common man saw little difference between such an enthroned central power and the Royal British Government which had been driven from American shores.

To be sure, not a large part of the half-million men able for the field891 had taken much of any militant part in expelling British tyranny; but these "chimney-corner patriots," as Washington stingingly described them, were the hottest foes of British despotism – after it had been overthrown. And they were the most savage opponents to setting up any strong government, even though it should be exclusively American.

Such were the economic, social, and educational conditions of the masses and such were their physical surroundings, conveniences, and opportunities between the close of the War for Independence and the setting-up of the present Government. All these facts profoundly affected the thought, conduct, and character of the people; and what the people thought, said, and did, decisively influenced John Marshall's opinion of them and of the government and laws which were best for the country.

During these critical years, Jefferson was in France witnessing government by a decaying, inefficient, and corrupt monarchy and nobility, and considering the state of a people who were without that political liberty enjoyed in America.892 But the vagaries, the changeableness, the turbulence, the envy toward those who had property, the tendency to repudiate debts, the readiness to credit the grossest slander or to respond to the most fantastic promises, which the newly liberated people in America were then displaying, did not come within Jefferson's vision or experience.

Thus, Marshall and Jefferson, at a time destined to be so important in determining the settled opinions of both, were looking upon opposite sides of the shield. It was a curious and fateful circumstance and it was repeated later under reversed conditions.

CHAPTER VIII

POPULAR ANTAGONISM TO GOVERNMENT

Mankind, when left to themselves, are unfit for their own government. (George Washington, 1786.)

There are subjects to which the capacities of the bulk of mankind are unequal and on which they must and will be governed by those with whom they happen to have acquaintance and confidence. (James Madison, 1788.)

I fear, and there is no opinion more degrading to the dignity of man, that these have truth on their side who say that man is incapable of governing himself. (John Marshall, 1787.)

"Government, even in its best state," said Mr. Thomas Paine during the Revolution, "is but a necessary evil."893 Little as the people in general had read books of any kind, there was one work which most had absorbed either by perusal or by listening to the reading of it; and those who had not, nevertheless, had learned of its contents with applause.

Thomas Paine's "Common Sense," which Washington and Franklin truly said did so much for the patriot cause,894 had sown dragon's teeth which the author possibly did not intend to conceal in his brilliant lines. Scores of thousands interpreted the meaning and philosophy of this immortal paper by the light of a few flashing sentences with which it began. Long after the British flag disappeared from American soil, this expatriated Englishman continued to be the voice of the people;895 and it is far within the truth to affirm that Thomas Paine prepared the ground and sowed the seed for the harvest which Thomas Jefferson gathered.

"Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise." And again, "Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness."896 So ran the flaming maxims of the great iconoclast; and these found combustible material.

Indeed, there was, even while the patriots were fighting for our independence, a considerable part of the people who considered "all government as dissolved, and themselves in a state of absolute liberty, where they wish always to remain"; and they were strong enough in many places "to prevent any courts being opened, and to render every attempt to administer justice abortive."897 Zealous bearers, these, of the torches of anarchy which Paine's burning words had lighted. Was it not the favored of the earth that government protected? What did the poor and needy get from government except oppression and the privilege of dying for the boon? Was not government a fortress built around property? What need, therefore, had the lowly for its embattled walls?

Here was excellent ammunition for the demagogue. A person of little ability and less character always could inflame a portion of the people when they could be assembled. It was not necessary for him to have property; indeed, that was a distinct disadvantage to the Jack Cades of the period.898 A lie traveled like a snake under the leaves and could not be overtaken;899 bad roads, scattered communities, long distances, and resultant isolation leadened and delayed the feet of truth. Nothing was too ridiculous for belief; nothing too absurd to be credited.

A Baptist preacher in North Carolina was a candidate for the State Convention to pass upon the new National Constitution, which he bitterly opposed. At a meeting of backwoodsmen in a log house used for a church, he told them in a lurid speech that the proposed "Federal City" (now the District of Columbia) would be the armed and fortified fortress of despotism. "'This, my friends,' said the preacher, 'will be walled in or fortified. Here an army of 50,000, or, perhaps 100,000 men, will be finally embodied and will sally forth, and enslave the people who will be gradually disarmed.'" A spectator, who attempted to dispute this statement, narrowly escaped being mobbed by the crowd. Everything possible was done to defeat this ecclesiastical politician; but the people believed what he said and he was elected.900

So bizarre an invention as the following was widely circulated and generally believed as late as 1800: John Adams, it was said, had arranged, by intermarriage, to unite his family with the Royal House of Great Britain, the bridegroom to be King of America. Washington, attired in white clothing as a sign of conciliation, called on Adams and objected; Adams rebuffed him. Washington returned, this time dressed in black, to indicate the solemnity of his protest. Adams was obdurate. Again the Father of his Country visited the stubborn seeker after monarchical relationship, this time arrayed in full regimentals to show his earnestness; Adams was deaf to his pleas. Thereupon the aged warrior drew his sword, avowing that he would never sheathe it until Adams gave up his treasonable purpose; Adams remained adamant and the two parted determined enemies.901

Such are examples of the strange tales fed to the voracious credulity of the multitude. The attacks on personal character, made by setting loose against public men slanders which flew and took root like thistle seed, were often too base and vile for repetition at the present day, even as a matter of history; and so monstrous and palpably untruthful that it is difficult to believe they ever could have been circulated much less credited by the most gossip-loving.

Things, praiseworthy in themselves, were magnified into stupendous and impending menaces. Revolutionary officers formed "The Society of the Cincinnati" in order to keep in touch with one another, preserve the memories of their battles and their campfires, and to support the principles for which they had fought.902 Yet this patriotic and fraternal order was, shouted the patriots of peace, a plain attempt to establish an hereditary nobility on which a new tyranny was to be builded. Jefferson, in Paris, declared that "the day … will certainly come, when a single fibre of this institution will produce an hereditary aristocracy which will change the form of our governments [Articles of Confederation] from the best to the worst in the world."903

Ædanus Burke,904 one of the Justices of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, wrote that the Society of the Cincinnati was "deeply planned"; it was "an hereditary peerage"; it was "planted in a fiery hot ambition, and thirst for power"; "its branches will end in Tyranny … the country will be composed only of two ranks of men, the patricians, or nobles, and the rabble."905 In France, Mirabeau was so aroused by Burke's pamphlet that the French orator wrote one of his own. Mirabeau called the Cincinnati "that nobility of barbarians, the price of blood, the off-spring of the sword, the fruit of conquest." "The distinction of Celts and Ostrogoths," exclaimed the extravagant Frenchman, "are what they claim for their inheritance."906

The "Independent Chronicle" of Boston was so excited that it called on "legislators, Governors, and magistrates and their ELECTORS" to suppress the Cincinnati because it "is concerted to establish a complete and perpetual personal discrimination between" its members "and the whole remaining body of the people who will be styled Plebeians."907

John Marshall was a member of this absurdly traduced patriotic fraternity. So were his father and fellow officers of our War for Independence. Washington was its commander. Were the grotesque charges against these men the laurels with which democracy crowned those who had drawn the sword for freedom? Was this the justice of liberty? Was this the intelligence of the masses? Such must have been the queries that sprang up in the minds of men like Marshall. And, indeed, there was sound reason for doubt and misgiving. For the nightmares of men like Burke and Mirabeau were pleasant dreams compared with the horrid visions that the people conjured.

Nor did this popular tendency to credit the most extraordinary tale, believe the most impossible and outrageous scandal, or accept the most impracticable and misshapen theory, end only in wholesome hatred of rank and distinction. Among large numbers there was the feeling that equality should be made real by a general division of property. Three years after peace had been established, Madison said he "strongly suspected" that many of the people contemplated "an abolition of debts public & private, and a new division of property."908 And Jay thought that "a reluctance to taxes, an impatience of government, a rage for property, and little regard to the means of acquiring it, together with a desire for equality in all things, seem to actuate the mass of those who are uneasy in their circumstances."909 The greed and covetousness of the people is also noted by all travelers.910

Very considerable were the obligations "public and private" which Madison wrote his father that he "strongly suspected" a part of the country intended to repudiate. The public debt, foreign and domestic, of the Confederation and the States, at the close of the Revolutionary War, appeared to the people to be a staggering sum.911 The private debt aggregated a large amount.912 The financial situation was chaos. Paper money had played such havoc with specie that, in Virginia in 1786, as we have seen, there was not enough gold and silver to pay current taxes.913 The country had had bitter experience with a fictitious medium of exchange. In Virginia by 1781 the notes issued by Congress "fell to 1000 for 1," records Jefferson, "and then expired, as it had done in other States, without a single groan."914

Later on, foreigners bought five thousand dollars of this Continental scrip for a single dollar of gold or silver.915 In Philadelphia, toward the end of the Revolution, the people paraded the streets wearing this make-believe currency in their hats, with a dog tarred and covered with paper dollars instead of feathers.916 For land sold by Jefferson before paper currency was issued he "did not receive the money till it was not worth Oak leaves."917

Most of the States had uttered this fiat medium, which not only depreciated and fluctuated within the State issuing it, but made trade between citizens of neighboring States almost impossible. Livingston found it a "loss to shop it in New York with [New] Jersey Money at the unconscionable discount which your [New York] brokers and merchants exact; and it is as damnifying to deal with our merchants here [New Jersey] in that currency, since they proportionably advance the price of their commodities."918 Fithian in Virginia records that: "In the evening I borrowed of Ben Carter 15/ – I have plenty of money with me but it is in Bills of Philadelphia Currency and will not pass at all here."919

Virginia had gone through her trial of financial fiction-for-fact, ending in a law fixing the scale of depreciation at forty to one, and in other unique and bizarre devices;920 and finally took a determined stand against paper currency.921 Although Virginia had burned her fingers, so great was the scarcity of money that there was a formidable agitation to try inflation again.922 Throughout the country there once more was a "general rage for paper money."923 Bad as this currency was, it was counterfeited freely.924 Such coin as existed was cut and clipped until Washington feared that "a man must travel with a pair of money scales in his pocket, or run the risk of receiving gold of one fourth less by weight than it counts."925