полная версия

полная версияJourneys in Persia and Kurdistan, Volume 2 (of 2)

1

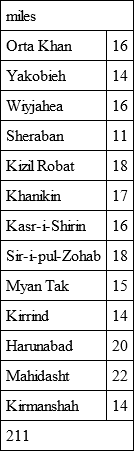

From Baghdad to Kirmanshah.

2

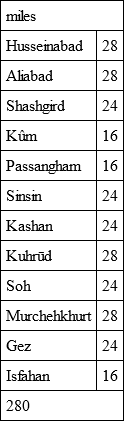

From Kirmanshah to Tihran.63

3

From Tihran to Isfahan.

5

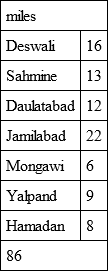

From Burujird to Hamadan.

6

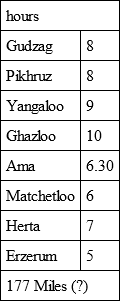

From Hamadan to Urmi.

7

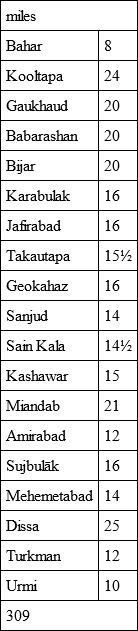

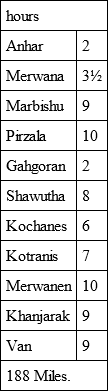

From Urmi to Van.

8

From Van to Bitlis.

9

From Bitlis to Erzerum.

10

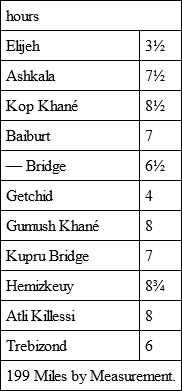

From Erzerum to Trebizond.

1

For the benefit of other travellers I add that the dose of salol was ten grains every three hours. I found it equally efficacious afterwards in several cases of acute rheumatism with fever. I hope that the general reader will excuse the medical and surgical notes given in these letters. I am anxious to show the great desire for European medical aid, and the wide sphere that is open to a medical missionary, at least for physical healing.

2

A few geographical paragraphs which follow here and on p. 35 are later additions to the letter.

3

Although the correct name of this river is undoubtedly Kurang, I have throughout adopted the ordinary spelling Karun, under which it is commercially and politically known.

4

Six Months in Persia.– Stack.

5

From Kalahoma for the rest of the route the predatory character of the tribes, the growing weakness of the Ilkhani's authority, the "blood feuds" and other inter-tribal quarrels, and the unsettled state of the Feili Lurs, produced a general insecurity and continual peril for travellers, which rendered constant vigilance and precautions necessary, as well as an alteration of arrangements.

6

A "Diz" is a natural fort believed to be impregnable.

7

To English people the Bakhtiaris profess great friendliness for England, and the opinion has been expressed by some well-informed writers that, in the event of an English occupation of the country, their light horse, drilled by English officers, would prove valuable auxiliaries. I am inclined, however, to believe that if a collision were to occur in south-west Persia between two powers which shall be nameless, the Bakhtiari horsemen would be sold to the highest bidder.

8

This untoward affair ended well, but had there been bloodshed on either side, had any one of us been killed, which easily might have been, the world would never have believed but that some offence had been given, and that some high-handed action had been the cause of the attack. I am in a position to say, not only that no offence was given, but that here and everywhere the utmost care was taken not to violate Bakhtiari etiquette, or wound religious or national susceptibilities; all supplies were paid for above their value; the servants, always under our own eyes, were friendly but reserved; and in all dealings with the people kindness and justice were the rule. I make these remarks in the hope of modifying any harsh judgments which may be passed upon any travellers who have died unwitnessed deaths at the hands of natives. There are, as in our case, absolutely unprovoked attacks.

9

See Appendix A.

10

I am inclined to estimate the Bakhtiari population at a higher figure than some travellers have given. I took forty-three men at random from the poorest class and from various tribes, and got from them the number of their families, wives and children only being included, and the average was eight to a household.

11

Book xvii. c. viii.

12

I have since heard that this youth was an accomplice of a Burujird man in this theft, and of an Armenian in a robbery of money which occurred in Berigun.

13

Throughout the part of Persia in which I have travelled I have observed a most remarkable discrepancy between the numbers of soldiers said to garrison any given place, and the number which on further investigation turned out to be actually there. It is safe to deduct from fifty to ninety per cent from the number in the original statement!

14

On this journey of 400 miles from Burujird to the Turkish frontier near Urmi, I never heard one complaint of the tribute which is paid to the Shah. All complaints, and they were many, were of the exactions and rapacity of the local governors.

15

North of Daulatabad, the route of last winter from Nanej to Kûm, the winter route from Kangawar to Tihran, was crossed. Although it is a "beaten track" for caravans, so far as I know the only information concerning it consists in two reports, not accessible to the public, in the possession of the Indian authorities.

16

Hamadan is the fourth city in the Empire in commercial importance. She has a Prince Governor, 450 villages in the district, raises revenue to the amount of 60,000 tumans, of which only 11,000 are paid into the Imperial Treasury, and, as the ancient Ecbatana, the capital of the Median kings, she has a splendid history, but the few lines in which I recorded my first impressions are not an exaggeration of the meanness and unsavouriness of her present externals.

17

For a detailed and most interesting account of these remarkable representations the reader is referred to Mr. Benjamin's Persia and the Persians, chap. xiii.

18

Since I returned I have been asked more than once, "What are the results of missions in Hamadan?" Among those which appear on the surface are the spiritual enlightenment of a number of persons whose minds were blinded by the gross and childish superstitions and the inconceivable ignorance into which the ancient church of S. Gregory the Illuminator has fallen. The raising of a higher standard of morals among the Armenians, so that a decided stigma is coming to be attached to drunkenness and other vices. The bringing the whole of the rising generation of Armenians under influences which in all respects "make for righteousness." The elevation of a large number of women into being the companions and helps rather than the drudges of men. The bestowing upon boys an education which fits them for any positions to which they may aspire in Persia and elsewhere, and creates a taste for intellectual pursuits. The introduction of European medicine and surgery, and the bringing them within the reach of the poorest of the people. The breaking down of some Moslem prejudices against Christians. The gradually ameliorating influence exercised by the exhibition of the religion of Jesus Christ in purity of life, in ceaseless benevolence, in truthfulness and loyalty to engagements, in kind and just dealing, in temperance and self-denial, and the many virtues which make up Christian discipleship, and the dissemination in the city and neighbourhood of a higher teaching on the duties of common life, illustrated by example, not in fits and starts, but through years of loving and patient labour.

19

Apparently it was always thus, for on a tablet at Persepolis occurs a passage in which the vice of lying is mentioned as among the external dangers which threatened the mighty empire of the Medes and Persians. "Says Darius the king: May Ormuzd bring help to me, with the deities who guard my house; and may Ormuzd protect this province from slavery, from decrepitude, from lying; let not war, nor slavery, nor decrepitude, nor lies obtain power over this province."

20

I have very great pleasure in acknowledging a heavy debt of gratitude to Persian officials, high and low, for the courtesy with which I was uniformly treated. It is my practice in travelling to make my arrangements very carefully, to attend personally to every detail, and to give other people as little trouble as possible, but in Persia, when off the beaten track, the insecurity of some of the roads, the need of guards at night when one is living in camp, and the frequent insubordination and duplicity of charvadars render a reference to the local authorities occasionally imperative; and not only has the needed help been given, but it has been given courteously, and I have always been treated as respectfully as an English lady would expect to be in her own country.

21

The general verdict of travellers in Persia is, that misrule, heavy taxation, the rapacity and villainy of local governors, and successive famines have reduced its small stationary population to a condition of pitiable poverty and misery, and this is doubtless true of much of the country, and of parts of it which I have traversed myself. But I can only write of things as I found them, and on this journey of 300 miles from Hamadan to Urmi I heard comparatively little grumbling. Many of the villages are contented with their taxation and landlords, in others there are decided evidences of prosperity, and everywhere there is abundance of material comfort, not according to our ideas, but theirs. As to clothing and food, the condition of the cultivators of that part of western Persia compares favourably with that of the rayats in many parts of India. But just taxation and a complete reform in the administration of justice are needed equally by the prosperous and unprosperous parts of Persia.

22

The truth is that since Persia broke the power of the Kurds ten years ago, at the time of the so-called Kurdish invasion, she has kept a somewhat tight hand over them, and her success in coercing them indicates pretty plainly what Turkey, with her fine army, could do if she were actually in earnest in repressing the disorder and chronic insecurity in Turkish Kurdistan.

23

While I was sleeping in a buffalo stable in Turkey two buffaloes quarrelled and there was a terrible fight, in which the huge animals interlocked their horns and broke them short off, bellowing fearfully. It took twenty men with ropes, or rather cables, two and a half inches in diameter, which are kept for the purpose, to separate them; and their thin skins, sensitive to insect bites and all irritations, were bleeding in every direction before they could be forced apart.

24

Christian women and girls share the work of the fields with the men.

25

It is a pleasant duty to record here the undeserved and exceeding kindness that I have met with from the American, Presbyterian, and Congregational missionaries in Persia and Asia Minor. It is not only that they made a stranger, although a member of the Anglican Church, welcome in their refined and cultured homes, often putting themselves to considerable inconvenience in order to receive me, but that they ungrudgingly imparted to me the interests of their work and lives, helping me at the cost of much valuable time and trouble with the complicated and often difficult arrangements for my farther journeys, showing in every possible way that they "know the heart of a stranger," being themselves "strangers in a strange land." Specially, I feel bound to acknowledge the kindness and hospitality shown to me by the Presbyterian missionaries in Urmi, who were aware that one object of my journey through North-West Persia was to visit the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Missions, which work on different and, I may say, opposite lines from their own.

26

The name of the town and lake is spelt variously Urmi, Urumi, Urumiya, Ourmia, and Oroomiah. The Moslems call it Urumi, and the Christians Urmi, to which spelling I have adhered.

27

At the present time, when the persecution of the Stundists in Russia is attracting considerable attention, it may interest my readers to hear that one of the earliest promoters of the Stundist movement was Yacub Dilakoff, a Syrian, and a graduate of the Old American College. He went to Russia thirty years ago, and was so horrified at the ignorance and gross superstition of the peasantry that he studied Russian in the hope of enlightening them, and to aid his purpose became an itinerant hawker of Bibles. The "common people heard him gladly," and among both the Orthodox and the Lutherans prayer unions were formed, from which those who frequented them received the name by which they are known, from stunde, hour.

28

In twenty-eight years after its establishment a conference of bishops, presbyters, and deacons, all of whom had received ordination in the Old Church, with preachers, elders, and missionaries, met and deliberated. "This conference adopted its own confession, form of government, and discipline – at first very simple. Some things were taken from the canons and rituals of the Old Church, others from the usages of Protestant Churches. The traditions of the Old Church were respected to some extent; for example, no influence has induced the native brethren to remit the diaconate to a mere service in temporalities. The deacons are a preaching order."

Of the subsequent history of this church the same authority writes as follows: —

"The missionaries in 1835 were welcomed by the ecclesiastics and people, and for many years an honest effort was made to reform the old body" (the Syrian Church) "without destroying its organisation. This effort failed, and a new church was gradually formed for the following reasons —

"(1) Persecution. The patriarch did all in his power to destroy the Evangelical work. He threatened, beat, and imprisoned the teachers and converts, and made them leave his fold. (2) Lack of discipline. The converts could no longer accept unscriptural practices and rank abuses that prevailed, and it became evident that there was no method to reform them. At every effort the rent was made worse. (3) Lack of teaching. The converts asked for better care, and purer and better teaching and means of grace than they found in the dead language, rituals, and ordinances of the Old Church.

"The missionaries were slow in abandoning the hope that the Nestorian Church would become reformed and purified; but their hope was in vain, their efforts therefore have been not to proselytise, but to leaven the whole people with Christian truth. The separation was made in no spirit of hostility or controversy. There was no violent disruption. The missionaries have never published a word against the Old Church ecclesiastics or its polity.

"The ordination of the Old Church has always been accepted as valid. The missionaries and the evangelical bishops have sometimes joined in the ordination services, and it would be difficult to draw the line when the Episcopal ordination ceased and the Presbyterian began in the Reformed body.

"The relation of the Presbyterian mission work to the old ecclesiastics is thus something different from that found among any other Eastern Christians. The Patriarch in office fifty years ago was at first very friendly to the missionaries, and personally aided in superintending the building of mission houses. Subsequently he did all in his power to break up the mission. The Patriarch now in office has taken the attitude of neutrality, with frequent indications of fairness and friendliness toward our work.

"The next in ecclesiastical rank is the Mattran (Syriac for Metropolitan), the only one left of the twenty-five Metropolitans named in the thirteenth century. The present incumbent recently made distinct overtures to our Evangelical Church to come to an understanding by establishing the scriptural basis of things essential, and allowing liberty in things non-essential. He fails, perhaps, to understand all the scriptural issues between us, but he has a sincere desire to walk uprightly and to benefit his people.

"Of the bishops, three have been united with the Reform, and died in the Evangelical Church. The three bishops in Kurdistan are friendly, and give their influence in favour of our schools.

"A large majority of the priests or presbyters of the Old Church, in Persia at least, joined the Reform movement, and as large a proportion of the deacons. In all, nearly seventy of the priests have laboured with the mission as teachers, preachers, or pastors, and more than half of these continue, and are members of our Synod. In some places the Reform has gathered nearly all the population within its influence. In many places it is not unusual to find half the population in our winter services. On the other hand, there are many places where the ecclesiastics are immoral and opposed, and ignorance and vice abound, and the Reform moves very slowly."

29

"By God's help: (1) To raise up and restore a fallen Eastern Church to take her place again amongst the Churches of Christendom. (2) To infuse spiritual life into a church which the oppression of centuries has reduced to a state of weakness and ignorance. (3) To give the Chaldæan or Assyrian Christians (a) a religious education on the broad principles of the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church; (b) a secular education calculated to fit them for their state of life, the common mistakes and dangers of over-education and of Europeanising education being most carefully guarded against. (4) To train up the native clergy, by means of schools and seminaries, to be worthy to serve before God in their high vocation, and to rise to their responsibilities as leaders and teachers of the people in their villages. (5) To build schools, of which at present there are none, owing to the extreme poverty and misery of the people. (6) To aid the Patriarch and Bishops by counsel, by encouragement, and by active support. (7) To reorganise the Chaldæan Church upon her ancient lines, to set in motion the ecclesiastical machinery now rusty through disuse, and to revive religious discipline amongst clergy and laity. (8) To print the ancient Chaldæan service-books. They are now only in MS., and the number of copies is totally insufficient for the supply of the parish churches."

30

"Old Syriac as a lesson means reading portions of Holy Scripture, and translating them into modern Syriac."

31

The absolute fact, however, is that Christian nations have not shown any zeal in communicating the blessings of Christianity to Persia and Southern Turkey. England has sent two missions – one to Baghdad, the other to Julfa. America has five mission stations in Northern and Western Persia, but not one in Southern Turkey or Arabia.

The populous shores of the Persian Gulf, the great tribes of the plains of the Tigris and Euphrates, the Ilyats of Persia, the important cities of Shiraz, Yezd, Meshed, Kashan, Kûm, Kirmanshah, and all Southern, Eastern, and Western Persia (excepting Hamadan and Urmi), are untouched by Christian effort! Propagandism on a scale so contemptible impresses intelligent Moslems as a sham, and is an injury to the Christianity which it professes to represent.

32

A name usually applied to the Roman Uniats at Mosul.

33

The mode of building mud houses was described in Letter VI. vol. i. p. 149.

34

Dr. Labaree, whose experience stretches back for thirty years, writes of the races under Persian rule in the Province of Azerbijan in the following terms: "The Nestorians and Armenians of Persia in common with their Mohammedan neighbours suffer from the evil forms of society and government which have been bequeathed to them from the earliest dawnings of history. Landlordism in its worst forms bears sway. The poor rayat or tenant must pay his landlord one-half or two-thirds of all the produce of his farm. Aside from his poll tax he must pay a tax on his house, his hayfields, and his fruit trees, and on all his stock with the exception of the oxen with which he tills the soil. But this is not all. He is virtually at the mercy of his Agha, which translated literally means master, a word which most correctly describes the relation of the landlord to his peasants. By law he may require from each of his rayats three days of labour without pay. In reality he makes them work for him as much as he sees fit. He helps himself to what he pleases whenever he makes them a visit. He sells them grain and flour above the market price. He ties them up and beats them for slight offences. And to all this and much else must the poor peasant submit for fear of worse persecutions if he complains. In these respects Moslem, Christian, and Jew suffer alike."

35

Later, I heard the same accusation brought against the Persian Kurds by a high official in Constantinople.

36

The national customs of the Syrians are endless, and in many ways very interesting. They are treated very fully in a scarce volume called Residence in Persia among the Nestorians, by Dr. Justin Perkins.

37

On this subject there can be no better authority than the Hon. George N. Curzon, M.P., who after careful study has estimated the total population of Persia at over nine millions.

38

In The Caliphate, its Rise, Decline, and Fall, a valuable recent work, its author, Sir W. Muir, K.C.S.I., dwells very strongly on the narrowing influence of Islam on national life, and concludes his review of it in the following words: "As regards the spiritual, social, and dogmatic aspect of Islam, there has been neither progress nor material change. Such as we found it in the days of the Caliphate, such is it also at the present day. Christian nations may advance in civilisation, freedom, and morality, in philosophy, science, and the arts, but Islam stands still. And thus stationary, so far as the lessons of its history avail, it will remain." In a chapter at the end of his book he deals with polygamy, servile concubinage, temporary marriages, and the law of divorce, as cankering the domestic life of Mohammedan countries, and infallibly neutralising all civilising influences.

39

I have since heard that these Kurds, a short time afterwards, betrayed some Christian travellers into the hands of some of their own people, by whom they were robbed and brutally maltreated.

40

I give the story as it was repeatedly told to me. It was a very shady and complicated transaction throughout.

41

Dr. Cutts, in his interesting volume, Christians Under the Crescent in Asia, gives the following translation of one of the morning praises, which forms part of the daily prayer. The earlier portion is chanted antiphonally in semi-choirs —

"Semi-choir – 1st. At the dawn of day we praise Thee, O Lord: Thou art the Redeemer of all creatures, give us by Thy mercy a peaceful day, and give us remission of our sins.