полная версия

полная версияAmerican Football

He will also be likely to have the long place-kicking to do. In fact, it is proper to practise him at this, because, if he be the best punter among the men behind the line, he can be made the longest place-kicker, and few realize the great advantage of these long place-kicks to a team upon occasion of fair catches.

Tackling, when it does fall to the lot of a full-back, comes with an importance the like of which no other player is ever called upon to face. It usually means a touch-down if he misses. For practice of this kind it is well to play the 'varsity back once in a while upon the scrub side. This is likely to improve the speed of his kicking also.

SIGNALS

When Rugby football was first adopted in this country, it was against a strong feeling that it would never make progress against what had been known as the American game. This old-fashioned game was much more like the British Association in a rather demoralized state. Not only was there no such thing as off-side, but one of the chief features consisted in batting the ball with the fist, at which many became sufficiently expert to drive the ball almost as far as the ordinary punter now kicks it. There was very little division of players by name, although they strung out along the field, and one (known as the "peanutter" – why, no one knows) played in the enemies' goal. Coming to players accustomed to this heterogeneous mingling, it is no great wonder that the first days of Rugby were characterized by even less system than that displayed in the old game.

The first division of players was into rushers, half-backs, and a goal-tend. The rushers had but little regard for their relative positions in the line; and as for their duties, one can easily imagine how little they corresponded with those of the rusher of to-day when it is said that it was by no means unusual for one of them to pick up the ball and punt it.

The snap-back and quarter-back play soon defined these two positions, and shortly after the individual rush line positions became distinct, both as regards location and duties. All this was an era of development of general play with but few particular combinations or marks of strategy. If a man made a run, he made it for the most part wherever he saw the best chance after receiving the ball, and he made it unaided to any degree by his comrades. If the ball was kicked, it was at the option of the man receiving it, and the forwards did not know whether he would kick or run.

It was at this point that the demand for signals first showed itself. The rushers began to insist upon it that they must be told in some way whether the play was to be a kick or a run. They maintained quite stoutly and correctly that there was no reason in their chasing down the field when the half-backs did not kick. As a matter of fact, the forwards even went so far as to contend that the running-game should be entirely dropped in favor of one based upon long kicks well followed up. Failing to establish this opinion, they nevertheless brought it about that they should be told by some signal what the play was to be, and so be spared useless running. This was probably the first of the present complicated system of signals, although at about the same time some teams took up the play of making a rather unsatisfactory opening for a runner in the line, and made use of a signal to indicate the occasions when this was to be done. The signalling of the quarter to the centre-rush as to when the ball should be played antedated this somewhat, but can hardly be classed with signals for the direction of the play itself.

To-day the teams which meet to decide the championship are brought up to the execution of at least twenty-five different plays, each of which is called for by a certain distinct signal of its own.

The first signals given were "word signals;" that is, a word or a sentence called out so that the entire team might hear it and understand whether a kick or a run was to be made. Then, when signals became more general, "sign-signals" (that is, some motion of the hand or arm to indicate the play) were brought in and became for a time more popular than the word signals, particularly upon fields where the audience pressed close upon the lines, and their enthusiastic cheering at times interfered with hearing word signals. Of late years numerical combinations have become most popular, and as the crowd is kept at such a distance from the side lines as to make it possible for teams to hear those signals, they have proven highly satisfactory. The numerical system, while it can be readily understood by the side giving the signal, because they know the key, is far more difficult for the opponents to solve than either the old word signals or signs. Still, the ingenuity of captains is generally taxed to devise systems that shall so operate as never to confuse their own men and yet completely mystify the opponents throughout the game. Clever forwards almost always succeed in interpreting correctly one or two of the signals most frequently used, in spite of the difficulty apparent in the solution of such problems. The question as to who should give the signals is still a disputed one, although the general opinion is that the quarter-back should perform this duty. There is no question as to the propriety of the signals emanating from that point, but the discussion is as to whether the captain or the quarter should direct the play. Of course all is settled if the captain is himself a quarter-back, but even when he is not he ought to be able to so direct his quarter previous to the actual conflict as to make it perfectly satisfactory to have the signals come from the same place as the ball. It is in that direction that the eyes and attention of every player are more or less turned, and hence signals there given are far more certain to be observed. Moreover, it is sometimes, and by no means infrequently, necessary to change a play even after the signal has been given. This, if the quarter be giving the signals, is not at all difficult, but is decidedly confusing when coming from some other point in the line.

The important fact to be remembered in selecting a system of signals is that it is far more demoralizing to confuse your own team than to mystify your opponents. A captain must therefore choose such a set of signals as he can be sure of making his own team comprehend without difficulty and without mistake. When he is sure of that, he can think how far it is possible for him to disguise these from his opponents. Among the teams which contest for championship honors it is unusual to find any which are not prepared for emergencies by the possession either of two sets of signals, or of such changes in the manner of giving them as to make it amount to the same thing. Considering the way the game is played at the present time, this preparation is advisable, for one can hardly overestimate the demoralizing effect it would have upon any team to find their opponents in possession of a complete understanding of the signals which were directing the play against them.

While it is well for the captain or coach to arrange in his own mind early in the season such a basis for a code of signals as to render it adaptable to almost indefinite increase in the number of plays, it is by no means necessary to have the team at the outset understand this basis. In fact, it is just as well to start them off very modestly upon two or three signals which they should learn, and of which they should make use until the captain sees fit to advance them a peg.

If, for instance, the captain decides to make use of a numerical system, he cannot do better to accustom his men to listening and following instructions than to give them three signals, something like this: One-two-three, to indicate that the ball is to be passed to the right half-back, who will endeavor to run around the left end; four-five-six, that the left half will try to run around the right end; and seven-eight-nine, that the back will kick. The scrub side will probably "get on" to these signals in short order, and will make it pleasant at the ends for the half-backs; but this will be the best kind of practice in team work, and will do no harm. After a day or two of this it will be time to make changes in the combination of numbers, not only with an idea of deceiving the scrub side, but also to quicken the wits of the 'Varsity team. Taking the same signals as a basis, the first, or signal for the right half-back to try on the left end, was one-two-three – the sum of these numbers is six. Take that, then, as the key to this signal, and any numbers the sum of which equals six will be a signal for this play. For instance, three-three, or four-two, two-three-one – any of these would serve to designate this play. Similarly, as the signal for the left half at the right end was four-five-six, or a total of fifteen, any numbers which added make fifteen – as six-six-three, seven-eight, or five-four-six – would be interpreted in this way. Finally, the signal for a kick having been seven-eight-nine, or a sum of twenty-four, any numbers aggregating that total would answer equally well.

A few days of this practice will fit the men for any further developments upon the same lines, and accustom them to listening and thinking at the same time. The greatest difficulty experienced by both captains and coaches since the signals and plays became so complicated has been to teach green players not to stop playing while they listen to and think out a signal. By the end of the season players are so accustomed to the signals that all this hesitation disappears, and the signal is so familiar as to amount to a description of the play in so many words.

The other two methods of signalling by the use of words rather than numbers, and signs given by certain movements, although they have now given way in most teams to numbers, are still made use of, and have merit enough to deserve a line or two. The word-signal was usually given in the form of a sentence, the whole or any part of which would indicate the play. As, for instance, to indicate a kick, the sentence "Play up sharp, Charlie." If the quarter, or whoever gave the signals, should call out, "Play up," or "Play up sharp," or "Play," or "Charlie," he would in each instance be giving the signal for a kick. Sign-signals are more difficult to disguise, but are none the less very effective, especially where there is a great amount of noise close to the ropes. A good example of the sign-signal is the touching of some part of the body with the hand. For instance, half-back running would be denoted by placing the hand on the hip, the right hip for the left half, and the left hip for the right half. A kick would be indicated by placing the hand upon the neck. Particular care should be exercised when sign-signals are to be used that the ones selected, while similar to the acts performed naturally by the quarter in stooping over to receive the ball, are never exactly identical with these motions, else there will likely enough be confusion.

No matter what method of signalling be used, there is one important feature to be regarded, and that is, some means of altering the play after a signal has been given. This is, of course, a very simple thing, and the usual plan is to have some word which means that the signal already given is to be considered void, and a new signal will be given in its place. There should also be some way of advising the team of a change from one set of signals to another, should such a move become necessary. It is very unwise not to be prepared for such an emergency, because if a captain is obliged to have time called and personally advise his team one by one of such a change, the opponents are quite sure to see it and to gain confidence from the fact that they have been clever enough to make such a move necessary.

TRAINING

At the present advanced athletic era there are very few who do not understand that a certain amount of preparation is absolutely essential to success in any physical effort requiring strength and endurance. The matter of detail is, however, not faced until one actually becomes a captain or a coach, and, as such, responsible for the condition, not of himself alone, but of a team of fifteen or twenty men.

Experience regarding his own needs will have taught him the value of care and work in this line; but, unless he differs greatly from the ordinary captain upon first assuming the duties of that position, his knowledge of training will be confined to an understanding of his own requirements, coupled with the handed-down traditions of the preceding captains and teams. When he finds himself in this position and considers what lines of training he shall lay down for his team, unless he be an inordinately conceited man he will wish he had made more of a study of this art of preparation, especially in the direction most suited to the requirements of his own particular sport.

Many inquiries from men about to undertake the training of a team have led me to believe that, even at the expense of going over old ground, it will be well in this book to map out a few of the important features of a course of training. It should go without saying that there are infinite variations in systems of this kind; but if a man will carry in mind the reasons rather than the rules, he has always a test to apply which will enable him to make the most of whatever system he adopts.

He should remember that training ought to be a preparation by means of which his men will at a certain time arrive at the best limits of their muscular strength and activity, at the same time preserving that equilibrium most conducive to normal health. Such a preparation can be accomplished by the judicious use of the ordinary agents of well-being – exercise, diet, sleep, and cleanliness.

One can follow out the reasons for or against any particular point in a system rather better if he cares to see why these agents act towards health and strength.

Exercise is a prime requisite, because the human mechanism, unlike the inanimate machine, gains strength from use. Muscular movement causes disintegration and death of substance, but at the same time there is an increased flow of blood to the part, and that means an increased supply of nourishment and increased activity in rebuilding. As MacLaren has expressed it, strength means newness of the muscle. The amount and quality of this exercise will be treated of later in this chapter.

In considering the matter of Diet, a captain or coach should think of this question not according to the tradition of his club, nor according to his own idiosyncrasies. He should regard the general principle of not depriving a man of anything to which he is accustomed and which agrees with him. Of course, it is advisable to do without such articles of food as would be injurious to the majority of the men, even though there might be one or two to whom they would do no harm. Men should enjoy their food, and it should be properly served. I remember once being asked my opinion regarding a certain team at the time in training, and I expressed the conviction that something was wrong with their diet. The team, as a whole, were not seriously affected, but some three or four were manifestly out of sorts. I heard the coach go over the bill of fare, and it sounded all right. I then decided to take dinner with them and see if I could discover the trouble. One meal was sufficient, for it was a meal! The beef – and an excellent roast it was, too – was literally served in junks, such as one might throw to a dog. The dishes were dirty, so was the cloth. Vegetables were dumped on to the plates in a mess, and each one grabbed for what he wanted. Some of the men might have been brought up to eat at such a table, still others were not sufficiently sensitive to have their appetites greatly impaired by anything, but the three or four who were "off" were boys whose home life had accustomed them to a different way of dining, and their natures revolted. So, too, did their appetites. As it was then too late to correct the manners of the mess, I simply advised sending these men elsewhere to board, and they speedily came into shape. I cannot too strongly advocate good service at a training table. The men should enjoy their dinners, should eat them slowly, and should be encouraged to be as long about it as they will. As food is to repair the waste, it should be generous in quantity and taken when the man will not, from being over-tired, have lost his appetite. Sometimes a team is not overworked, but worked too late in the day, so that the men rush to the table almost directly from the field, and fail to feel hungry, while within an hour they would have eaten with a zest. This course persevered in for several days will show its folly in a general falling-off in the strength as well as the weight of the men. To train a football team should be, in the matter of the diet at least, the simplest matter compared with training for other sports, because the season of the year is so favorable to good condition.

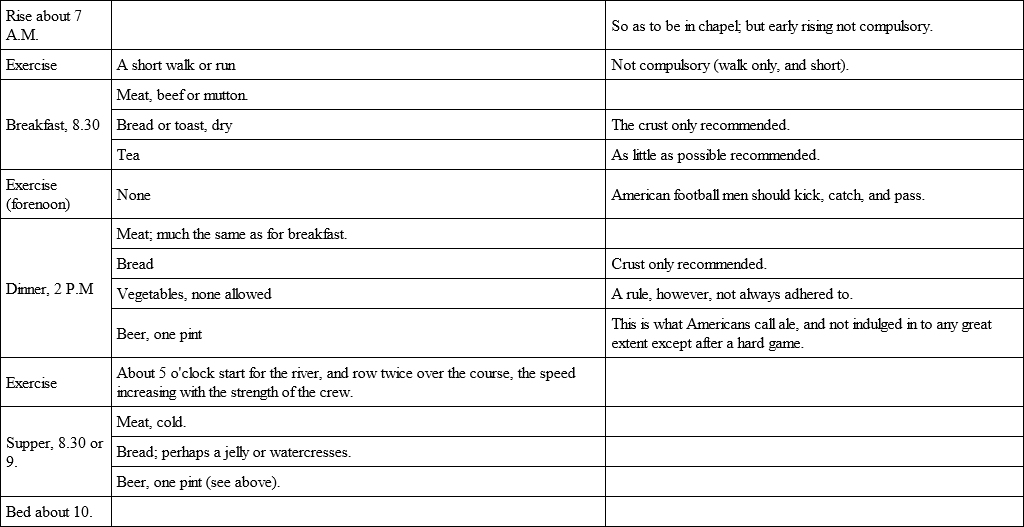

Crews and ball nines have oftentimes the trial of exceptionally hot and exhausting weather to face, while a football team, after the few warm days of September are passed, enjoy the very best of bracing weather – weather which will give almost any man who spends his time in out-door work a healthy, hearty appetite. In order that any captain or coach reading this book may feel that, while it offers several courses of diet, it would emphatically present the fact that there is no hard-and-fast system of diet that must be religiously followed, I submit a variety of tables, showing some old as well as new school diets. None of them are very bad, several are excellent; and I don't think that a captain or coach would be called upon to draw his pencil through very many of the items enumerated.

THE OXFORD SYSTEM. – (Summer Races.)

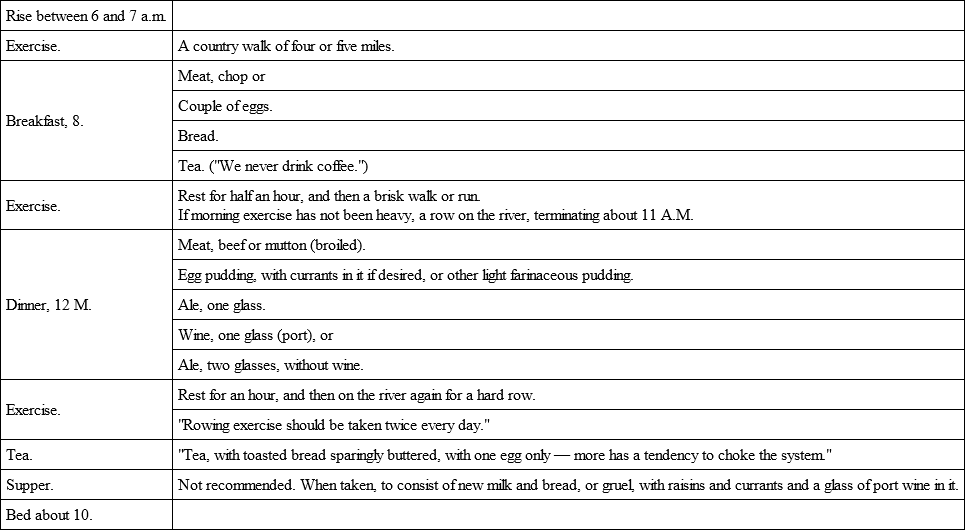

A DAY'S TRAINING. 1

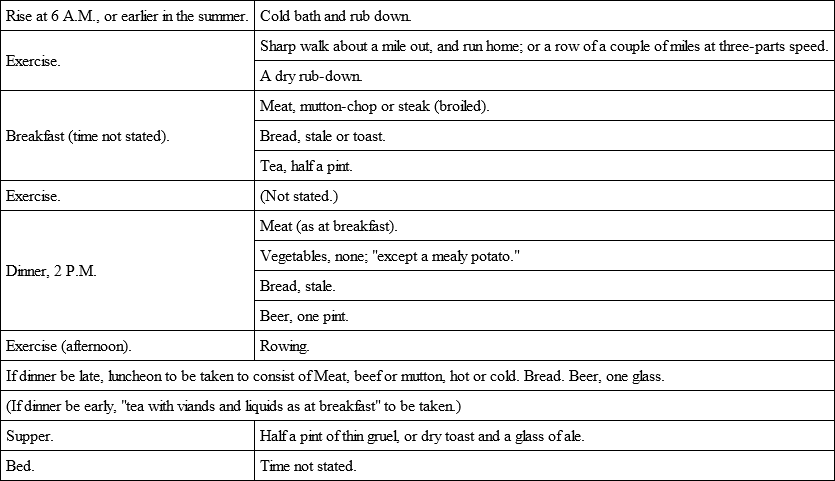

TORPID RACES.

A DAY'S TRAINING.

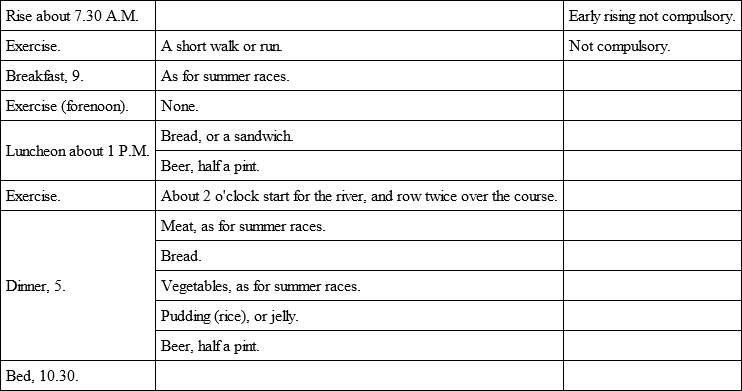

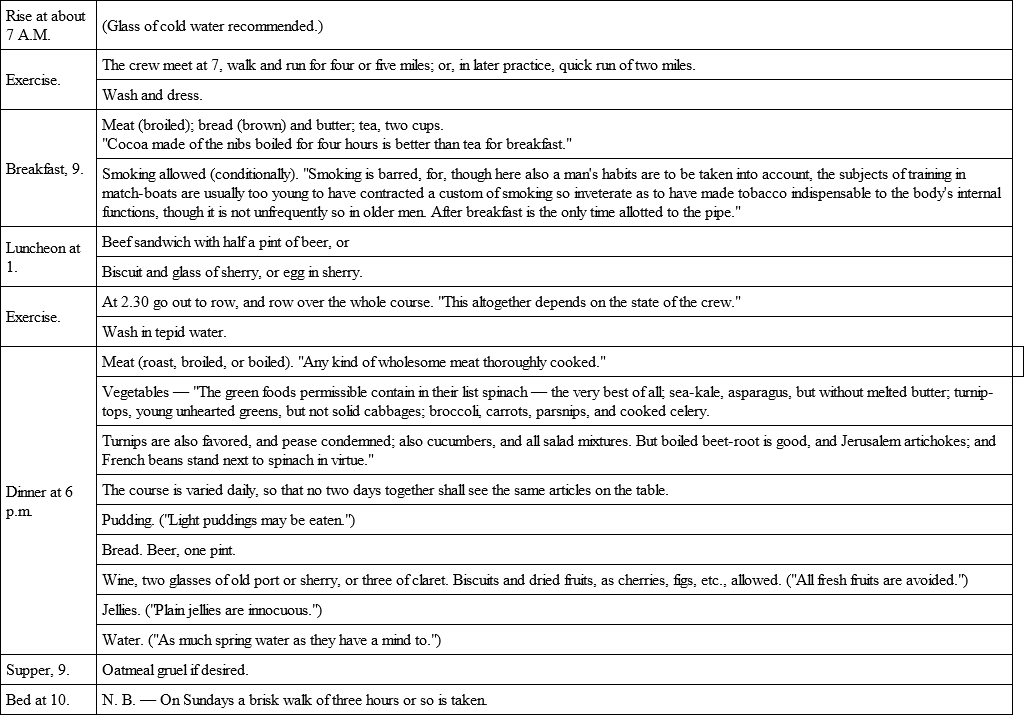

THE CAMBRIDGE SYSTEM. Summer Races (1866).

A DAY'S TRAINING.

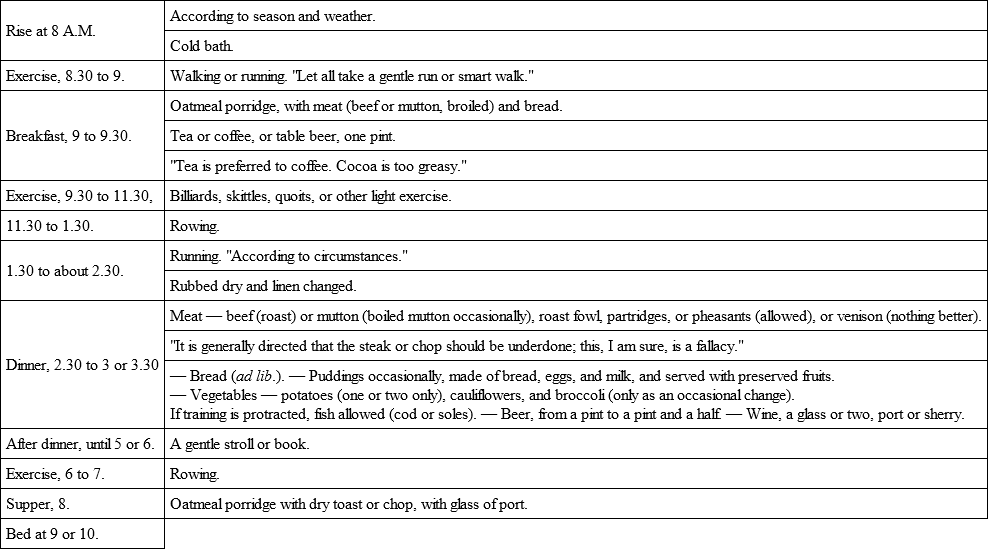

H. CLASPER'S SYSTEM.

A DAY'S TRAINING.

C. WESTHALL'S SYSTEM. For Amateurs.

A DAY'S TRAINING.

N.B. – It is added "that the above rules are of course open to alteration according to circumstances, and the diet varied successfully by the introduction of fowls, either roast or boiled – the latter preferred;" and "it must never be lost sight of that sharp work, regularity, and cleanliness are the chief if not the only rules to be followed to produce thorough good condition."

McLAREN'S SYSTEM.

A DAY'S TRAINING.

Summary.

Sleep, eight or nine hours. Exercise, about three hours. Diet, very varied.

STONEHENGE'S SYSTEM.

A DAY'S TRAINING.

Breakfast. – Stale or whole-meal bread, or toast, a little butter, plenty of marmalade if you like, but not jam. Bacon and eggs, or chops or steaks, with watercress if obtainable. To those who like it, a basin of oatmeal porridge, properly made, taken with pure milk about an hour before breakfast, is an excellent thing, and has a very beneficial effect upon the stomach, but it should not be taken every day. It is better to miss it every third day, or to take it regularly for a fortnight and then omit it from the next week's diet, as the too frequent use of it is rather injurious to the skin of some persons. Tea – not too strong – is better than coffee. Good ripe fruit is a capital adjunct to the breakfast-table, and is an excellent article of food.

Dinner. – Lamb, mutton, beef, fowl (tender and boiled), varied by fish, of which haddock, whiting, and soles are the best, with potatoes (well boiled, and not much of them), and well-cooked vegetables, followed by a small allowance of light farinaceous pudding or stewed fruit, will be a good, wholesome diet. If you want bread, have it stale. Never eat new bread. Avoid all sauces, or made dishes, and adhere to plain food only. One thing we would particularly impress upon the reader, and that is never to take his exercise immediately before or after meals, nothing is more injurious, or likely to produce indigestion, and its concomitant evils. Some authorities abjure the use of sugar, but taken in moderation it is not injurious. A well-known champion of our acquaintance, when in the pink of condition, was wont to amuse himself by eating the contents of a sugar basin, if one were inadvertently left near him, and without feeling any ill effects from so doing. Our readers need not follow his example, for although it might suit him, it probably would not agree with them. We have said, take sugar in moderation. Now, in this last word lies all the lectures one can give on this subject. Be moderate in all things, one might say, but above all things be moderate in the use of all edibles not actually necessary to support the increased exertion which a man in training is called upon to perform. No liquid should be taken except with, or just after meals, but we would not advise stinting the quantity too much. In summer three or four pints, and in winter two or three pints per diem would be about the quantity. Never drink just before exercise, and it is better not to drink just before going to bed. In fact, the less one has to digest when retiring for sleep the better, and be sure not to drink tea late at night.

Tea, or supper, should be taken at least two hours before bedtime, and we would allow a small chop, or some light fish, bread, and very little butter, with some ripe fruit. The best meal to take before a race, and which should be taken about two hours before starting-time, is the lean of mutton-chops and a little dry toast. We have said that no liquids should be taken except at meal-times; but we do not intend to state that if a man be very thirsty he may not touch them. If he does so, it must be a very small quantity. Thirst can often be assuaged by rinsing the mouth out with cold water, and this is by far the better plan if it is efficacious.

A COMMON-SENSE SYSTEMOne author says: "Rise at six; bathe; take about two ounces (a small cup) of coffee with milk: this is really a stimulating soup. Then light exercise, chiefly devoted to lungs; a little rest; the breakfast of meat, bread, or oatmeal, vegetables, with no coffee; an hour's rest. Then the heaviest exercise of the day. This is contrary to rule; but I believe the heaviest exercise should be taken before the heaviest meal; a rest before dinner. This meal, if breakfast be taken at seven or eight, should be at one or two, not leaving a longer interval than five hours between the meals. At dinner, again meat, vegetables, bread, perhaps a half-pint of malt liquor, no sweets. Then a longer rest; exercise till five. Supper light – bread, milk, perhaps with an egg. Half an hour later a cup of tea, and bed at nine."

J. B. O'REILLYSeven o'clock is a good time for an athlete in training to rise. He ought to get a good dry-rubbing, and then sponge his body with cold water, or have a shower-bath, with a thorough rubbing afterwards. He will then go out to exercise before breakfast, not to run hard, as is commonly taught, but to walk briskly for an hour, while exercising his lungs in deep-breathing. Before this walk, an egg in a cup of tea, or something of the kind, should be taken.

The breakfast need not always consist of a broiled mutton-chop or cutlet; a broiled steak, broiled chicken, or broiled fish, or some of each, may be taken with tea or coffee.

Dinner may be far more varied than is usually allowed by the trainer's "system." Any kind of butcher's meat, plainly cooked, with a variety of fresh vegetables, may be taken, with ordinary light puddings, stewed fruit, but no pastry. A good time for dinner is one o'clock.