полная версия

полная версияBacon and Shakespeare

So far as Shakespeare’s handwriting is concerned, I do not propose at the present moment to go beyond the opinion of Spedding. It would profit nothing to enter into a discussion on the subject until one has something tangible in the way of evidence to offer. Shakespeare’s Will, for instance, has always been regarded as a witness for the Baconian case, but if the result of the investigations I am prosecuting confirm my suspicions, it will become a piece of important evidence for Shakespeare. The bona-fides of this Will have always appeared to be more than questionable, and I am hopeful of being in a position shortly to connect it with the great fraud which I am satisfied has been perpetrated by Bacon.

The Bi-Literal Cipher

The most interesting feature of the Bacon-Shakespeare controversy at the present moment is the alleged discovery by Mrs. Elizabeth Wells Gallup, of Detroit, U.S.A., of a bi-literal cipher by Bacon, which appears in no fewer than forty-five books, published between 1591 and 1628. Mrs. Gallup was assisting Dr. Orville W. Owen (also of Detroit, U.S.A.), in the preparation of the later books of his Sir Francis Bacon’s Cipher Story, and in the study of the “great word cipher,” discovered by Dr. Owen, when she became convinced that the very full explanation found in De Augmentis Scientiarum of the bi-literal method of cipher-writing, was something more than a mere treatise on the subject. She applied the rules given to the peculiarly italicised words, and “letters in two forms,” as they appear in the photographic facsimile of the 1623 folio edition of the Shakespeare plays. The surprising disclosures that resulted from the experiment, sent her to the original editions of Bacon’s known works, and from those to all the authors whose books Bacon claimed as his own. The bi-literal cipher, according to Mrs. Gallup, held true in every instance, and she is fully entitled to have her discovery thoroughly investigated before it is condemned as a “pure invention.” Mrs. Gallup solemnly declares her translation to be “absolutely veracious,” and until it is authoritatively declared that the bi-literal cipher does not exist in the works in which she professes to have traced it, I am not prepared to question her bonâ fides. Her conclusions are absurd, but her premises may be proved to be impregnable. She is convinced of the soundness of her discoveries, and she forthwith leaps to the conclusion that “the proofs are overwhelming and irresistible, that Bacon was the author of the delightful lines attributed to Spenser – the fantastic conceits of Peele and Greene – the historical romances of Marlowe – the immortal plays and poems put forth in Shakespeare’s name – as well as the Anatomy of Melancholy of Burton.” Mrs. Gallup shows scant appreciation of the illimitable genius she claims for Bacon in this sentence.

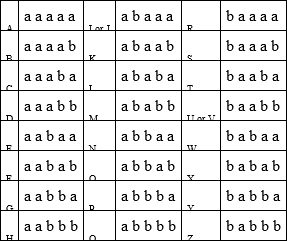

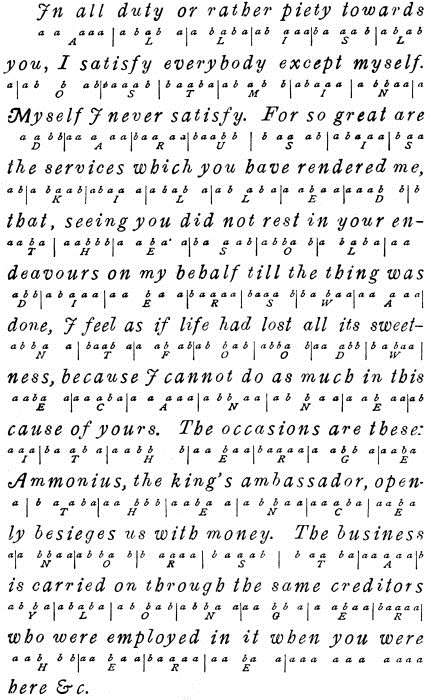

The inaccurately described bi-literal cipher, which Bacon, who claims to have invented it, explained with great elaboration in his De Augmentis Scientiarum, has nothing whatever to do with the composition or the wording of the works in which it is said to exist. It depends not on the author, but on the printer. It is altogether a matter of typography. One condition alone is necessary – control over the printing, so as to ensure its being done from specially marked manuscripts, or altered in proof. It shall, as Bacon says, be performed thus: – “First let all the letters of the alphabet, by transposition, be resolved into two letters only – hence bi-literal – for the transposition of two letters by five placings will be sufficient for 32 differences, much more than 24, which is the number of the alphabet. The example of such an alphabet is on this wise: —

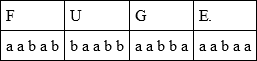

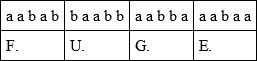

For the purpose of introducing this alphabet into the book which is to contain the secret message, certain letters are taken to stand for “a’s” and others for “b’s.” In Bacon’s illustration, he employed two different founts of italic type, using the letters of fount “a” to stand for “a’s,” and the letters of fount “b” to stand for “b’s.” Bacon takes the word “fuge” to exhibit the application of the alphabet, thus: —

The word is enfolded, as an illustration, in the sentence Manere te volo donec venero, as follows: —

Manere te volo donec venero

A more ample example of the cipher is given on the page which is here reproduced from Mrs. Gallup’s book. The work in which the “interiour” letter is enfolded is the first Epistle of Cicero, and the cipher letter it contains is as follows:

All is lost. Mindarus is killed. The soldiers want food.

We can neither get hence nor stay longer here.

Cicero’s First Epistle

(Note) – This Translation from Spedding, Ellis & Heath Ed.

Bacon had a three-fold motive for putting his cipher into every book of merit that was published in his day. In the first place, it allowed him to claim the authorship of the book. In the second, in Mrs. Gallup’s own words, “it was the means of conveying to a future time the truth which was being concealed from the world concerning himself – his right to be King of England – secrets of State regarding Queen Elizabeth – his mother – and other prominent characters of that day – the correction of English history in important particulars, the exposure of the wrongs that had been put upon him;” and, equally important, thirdly, of publishing his version of the wrongs he had done to others, and to Essex in particular. Concerning the amazing diversity of style displayed in the many works, he says in his cipher: “I varied my stile to suit men, since no two shew the same taste and like imagination…” “When I have assum’d men’s names, th’ next step is to create for each a stile naturall to the man that yet should let my owne bee seene, as a thrid of warpe in my entire fabricke.” His explanation of the diversity of merit that is displayed in the works of Robert Greene and of Shakespeare, is not less interesting and instructive. “It shall bee noted in truth that some (plays) greatly exceede their fellowes in worth, and it is easily explained. Th’ theame varied, yet was alwayes a subject well selected to convey the secret message. Also the plays being given out as tho’gh written by the actor, to whom each had bin consign’d, turne one’s genius suddainlie many times to suit th’ new man.”

“In this actour that wee now emploie (the cipher appears in the 1611 quarto edition of Hamlet), is a wittie veyne different from any formerly employ’d. [Bacon appears to have forgotten that he employed the ‘masque’ of Shakespeare in the quarto editions of Richard II. (1598), Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, The Merchant of Venice (1600), and of King Lear, Henry V. (1608), and Pericles (1609)]. In truth it suiteth well with a native spirrit, humourous and grave by turnes in ourself. Therefore, when wee create a part that hath him in minde, th’ play is correspondingly better therefor.”

In the cipher story which is found by Mrs. Gallup in Titus Andronicus, Bacon again recurs to the superior merit of the plays put forth in Shakespeare’s name, and he extols the merits of Shakespeare as an interpreter of these dramas: —

“We can win bayes, lawrell gyrlo’ds and renowne, and we can raise a shining monumente which shale not suffer the hardly wonne, supremest, crowning glory to fade. Nere shal the lofty and wide-reaching honor that such workes as these bro’t us bee lost whilst there may even a work bee found to afforde opportunity to actors – who may play those powerful parts which are now soe greeted with great acclayme – to winne such names and honours as Wil Shakespear, o’ The Glob’ so well did win, acting our dramas.

“That honour must to earth’s final morn yet follow him, but al fame won from th’ authorshippe (supposed) of our plays must in good time – after our owne worke, putting away its vayling disguises, standeth forth as you (the decipherer) only know it – bee yeelded to us.”

If Mr. Mallock reposes any confidence in his Bacon – according to Mrs. Gallup – he must at once withdraw his description of Shakespeare as a “notoriously ill-educated actor.” Bacon himself, in the foregoing, acknowledges that Will Shakespeare derived a well-won reputation and honours by acting in his dramas. At the same time Bacon is confident that the dramas will win for him, as author, “supremest, crowning, and unfading glory.”

Here, almost at the outset of these cipher revelations, we are met by a passage, plausible in itself, but which, read in the light of our knowledge of Bacon’s doubts upon the permanency of the English language, calls for careful consideration. Bacon rested his fame upon his Latin writings. He wrote always for the appreciation of posterity. As he advanced in years, he appears, says Abbott, to have been more and more impressed with the hopelessness of any expectations of lasting fame or usefulness based upon English books. He believed implicitly that posterity would not preserve works written in the modern languages – “for these modern languages will at one time or other play the bank-rowtes (bankrupts) with books.” Of his Latin translation of the Advancement of Learning, he said, “It is a book I think will live, and be a citizen of the world, as English books will not,” and he predicted that the Latin volume of his Essays would “last as long as books shall last.” So confident was he that his writings would achieve immortality, that he dedicated his Advancement of Learning to the King, in order that the virtues and mental qualities of his Majesty might be handed down to succeeding ages in “some solid work, fixed memorial, and immortal monument.” Bacon’s pride in his work was monumental, his “grasp on futurity” was conceived in a spirit of “magnificent audacity;” every scrap of his writings was jealously preserved and robed in the time-resisting garments of a dead language. Is it conceivable in this magnificent egoist that he should have displayed such gross carelessness, such wanton unconcern in his plays that, but for the labours of a couple of actors in collecting and arranging them, they would have been utterly lost? It is simply incredible that Bacon should have based his anticipation of immortality upon plays which for years were tossed about the world in pirated and mutilated editions, and in many instances, until the issue of the first folio in 1623, existed only in the form of the actor’s prompt books. The sixteen plays, in quarto, which were in print in 1616, were published without the co-operation of the author. They were to win for their author unfading glory, yet he was at no pains to collect them. The first folio was printed from the acting versions in use by the company with which Shakespeare had been associated, and the editorial duties were undertaken by two of Shakespeare’s friends and fellow actors, whose motives rather than their literary fitness for the task call for commendation. It was dedicated to two noblemen, with whom, so far as we know, Bacon had no social or political intercourse.

Mr. Theobald considers that Bacon’s “confident assurance of holding a lasting place in literature,” his anticipation of immortality, could only have been advanced by the man who voiced the same conviction in the Shakespeare Sonnets. The deduction is based on arbitrary conjecture, and a limited acquaintance with the literary conceits of the time. But Shakespeare claimed as his medium of immortality the language which Bacon predicted could not endure.

“So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see —So long lives this, and this gives life to Thee,”wrote Shakespeare. This was English, the purest and the sweetest that tongue ever uttered, and Bacon was dressing his thoughts in Latin that they might outlive the language which Shakespeare wrote. Ronsard and Desportes, in France, and in England, Drayton, Daniel, and, indeed, all the Elizabethan poets, had made the topic a commonplace. In his Apologie for Poetrie, Sir Philip Sidney wrote that it was the custom of poets “to tell you that they will make you immortal by their verses,” and both Shakespeare and Bacon adopted the current conceit when they referred to the “eternising” faculty of their literary effusions. It is not claimed by, or for, Bacon that he was the author of Drayton’s Idea or Daniel’s Delia, but if Mr. Theobald’s style of reasoning is to be taken at his own valuation, the master of Gorhambury, and none other, was responsible for the poetic output of both these singers.

Bacon’s “Sterne and Tragicle History.”

We are assured by another Baconian student that the Shakespeare plays were not an end, but merely a means to an end, the end being the revelation of Bacon’s history, and the composition of further plays and poems from the material which he had warehoused in the dramas attributed to Shakespeare and other authors. The initial, and most important fact which Mrs. Gallup’s deciphered story reveals, is, not that Francis Bacon was the author of Shakespeare’s plays, but that he was the legitimate son of Queen Elizabeth, by Robert Dudley, afterwards Earl of Leicester. The disclosure is so startling, so quaint, so incredible, and withal so interesting, that the revelation both appeals to and outrages our credulity. From our knowledge of Elizabeth and of Bacon, we can more readily believe that the Queen was the mother of Bacon, than that Bacon was the father of Shakespeare’s plays. At Gorhambury is to be seen a pair of oil paintings, by Hilliard, of Elizabeth and Leicester. The pictures are a match in size, style, and treatment. The doublet in which Leicester is portrayed is of the same material as that of the gown in which the Queen is represented. Moreover, they were a present from Elizabeth to Sir Nicholas Bacon, the foster father of Francis, who signs his cipher revelations, “Francis First of England,” “Francis Bacon (Rightful) R,” “F.B. or T.” or “Francis of E.”, as the humour seized him.

The deciphered secret story, the “sterne and tragicle” history of Bacon’s political wrongs commences in the first edition of Edmund Spenser’s Complaints (1590 and 1591); but it was not until the Faerie Queene was published (1596) that he appropriates the authorship of Spenser’s works. His first care is to establish his claim to the throne:

“Our name is Fr. Bacon, by adoption, yet it shall be different. Being of blood roial (for the Queen, our sov’raigne, who married by a private rite the Earle Leicester – and at a subseque’t time, also, as to make surer thereby, without pompe, but i’ th’ presence o’ a suitable number of witnesses, bound herselfe by those hymeneall bands againe – is our mother, and wee were not base-born, or base-begot), we be Tudor, and our stile shall be Francis First, in all proper cours of time, th’ King of our realme.

“Early in our life, othe (oath) – or threat as binding in effect as othe, we greatly doubt – was made by our wilful parent concerning succession, and if this cannot bee chang’d, or be not in time withdrawn, we know not how the kingdome shall be obtain’d. But ’tis thus seene or shewn that it can bee noe other’s by true desce’t, then is set down. To Francis First doth th’ crowne, th’ honor of our land belong…”

Thus Bacon states his case, and through the succeeding 368 pages of Mrs. Gallup’s book he repeats the assertion ad nauseam. He makes no attempt to prove his claim – he early allows it to be understood that he is unable to verify his asseverations, nor does he explain how or why his name should be Tuder, or Tidder. As the son of Lord Robert Dudley, he would be a Dudley. The circumstantial evidence with which he supports his case is interesting, but valueless; his conclusions are unproven, his facts are something more than shaky. But let us pursue the story:

“We, by men call’d Bacon, are sonne of the Sov’raigne, Queene Elizabeth, who confin’d i’ th’ Tow’r, married Ro. D.”

Elizabeth, it appears, was once “so mad daring” as to dub Bacon, “as a sonne of Follie,” to “th’ courageous men of our broadland.” But —

“No man hath claime to such pow’r as some shal se in mighty England, after th’ decease of Virgin Queene E – by dull, slow mortalls, farre or near, loved, wooed like some gen’rously affected youth-loving mayden, whylst she is both wife to th’ noble lord that was so sodainly cut off in his full tide and vigour of life and mothe’ – in such way as th’ women of the world have groaninglie bro’t foorth, and must whilst Nature doth raigne – of two noble sonnes, Earle of Essex, trained up by Devereux, and he who doth speake to you, th’ foster sonne of two wel fam’d frie’ds o’ th’ Que., Sir Nichola’ Bacon, her wo’thie adviser and counsellor, and that partne’ of loving labor and dutie, my most loved Lady Anne Bacon…”

“… My mother Elizabeth … join’d herselfe in a union with Robert Dudley whilst th’ oath sworne to one as belov’d yet bound him. I have bene told hee aided in th’ removall of this obstructio’, when turni’g on that narrowe treach’rous step, as is naturall, shee lightly leaned upon th’ raile, fell on th’ bricks – th’ paving of a court – and so died.”

“In such a sonne,” Bacon proceeds, “th’ wisest our age thus farr hath shewen – pardon, prithee, so u’seemly a phrase, I must speake it heere – th’ mother should lose selfish vanitie, and be actuated only by a desire for his advancement.”

Bacon is confident that the Queen would have acknowledged his claims but for the advice of a “fox seen at our court in th’ form and outward appearance of a man named Robbert Cecill, the hunchback,” who poisoned Elizabeth’s mind against her “sonne of Follie.” Both “Francis Tudor” (or Tidder), and his brother Essex, the “wrong’d enfan’s of a Queene,” learned that their “royall aspirations” were to receive “a dampening, a checke soe great, it co’vinc’d both, wee were hoping for advanceme’t we might never attaine.”

The “royall aspirations” of the Earl of Essex were cut short by the sentence of death that was passed upon him by “that mère and my owne counsel. Yet this truth must at some time be knowne; had not I allow’d myselfe to give some countenance to th’ arraingement, a subsequent triall, as wel as th’ sentence, I must have lost th’ life that I held so pricelesse.” And Bacon, or Francis Tidder, solaces himself, and condones his part in the deed with the reflection that, “Life to a schola’ is but a pawne for mankind.”

Queen Elizabeth, Bacon tells us, though already wedded “secretly to th’ Earle, my father, at th’ Tower of London, was afterwards married at the house of Lord P – …”

Briefly, then, we have it, on the authority of the cipher translation, that “Bacon was the son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, who were married in the Tower between 1554 and 1558. Leicester’s wife did not meet with her fatal accident until 1560. Bacon was born in January, 1561. His parents were subsequently re-married, at a date not stated, at the house of Lord P – .”

In 1611 (Shepheard’s Calendar) Bacon declares “Ended is now my great desire to sit in British throne. Larger worke doth invite my hand than majestie doth offer; to wield th’ penne dothe ever require a greater minde then to sway the royall scepter. Ay, I cry to th’ Heavenly Ayde, ruling ore all, ever to keepe my soule thus humbled and contente.” But in 1613 (Faerie Queene), he says, that “in th’ secrecy o’ my owne bosome, I do still hold to th’ faith that my heart has never wholly surrendered, that truth shall come out of error, and my head be crowned ere my line o’ life be sever’d. How many times this bright dreeme hath found lodgement in my braine!.. It were impossible, I am assurr’d, since witnesses to th’ marriage, and to my birth (after a proper length of time) are dead, and the papers certifying their presence being destroyed, yet is it a wrong that will rise, and crye that none can hush.” In 1620 (Novum Organum) he has lost his “feare, lest my secret bee s’ented forth by some hound o’ Queen Elizabeth;” but “the jealousy of the King is to be feared, and that more in dread of effecte on the hearts of the people, then any feare of th’ presentation of my claime, knowing as he doth, that all witnesses are dead, and the requir’d documents destroy’d.”

Bacon, according to the cipher, was sixteen years of age when he learned the truth of his parentage through the indiscretion of one “th’ ladies o’ her (the Queen’s) train, who foolish to rashnesse did babble such gossip to him as she heard at the Court.” Bacon, it seems, taxed the Queen forthwith with her motherhood of him, and Elizabeth, with “much malicious hatred” and “in hastie indignation,” said:

“You are my own borne sonne, but you, though truly royall, of a fresh, a masterlie spirit, shall rule not England, or your mother, nor reigne on subjects yet t’ bee. I bar from succession forevermore my best beloved first borne that bless’d my unio’ with – no, I’ll not name him, nor need I yet disclose the sweete story conceal’d thus farre so well, men only guesse it, nor know o’ a truth o’ th’ secret marriages, as rightfull to guard the name o’ a Queene, as of a maid o’ this realm. It would well beseeme you to make such tales sulk out of sight, but this suiteth not t’ your kin’ly spirit. A sonne like mine lifteth hand nere in aide to her who brought him foorth; hee’d rather uplift craven maides who tattle thus whenere my face (aigre enow ev’r, they say) turneth from them. What will this brave boy do? Tell a, b, c’s?”

“Weeping and sobbing sore,” Bacon hurries to Mistres Bacon’s chamber and entreats her to assure him that he is “the sonne of herselfe and her honored husband… When, therefore, my sweet mother did, weeping and lamenting, owne to me that I was in very truth th’ sonne o’ th’ Queene, I burst into maledictio’s ’gainst th’ Queene, my fate, life, and all it yieldeth… I besought her to speak my father’s name… She said, ‘He is the Earle of Leicester… I tooke a solemne oath not to reveale your storie to you, but you may hear my unfinish’d tale to th’ end and if you will, go to th’ midwife. Th’ doctor would be ready also to give proofes of your just right to be named th’ Prince of this realm, and heire-apparent to the throne. Nevertheless, Queen Bess did likewise give her solemn oath of bald-faced deniall of her marriage to Lord Leicester, as well as to her motherhood. Her oath, so broken, robs me of a sonne. O Francis, Francis, breake not your mother’s hearte. I cannot let you go forth after all the years you have beene the sonne o’ my heart. But night is falling. To-day I cannot speak to you of so weighty a matter. This hath mov’d you deeply, and though you now drie your eyes, you have yet many teare marks upon your little cheeks. Go now; do not give it place i’ thought or word; a brain-sick woman, though she be a Queene, can take my sonne from me.’” So Bacon leaves her, not to search for the midwife, or cross-question the doctor, but to “dreame of golden scepters, prou’ courts, and by-and-bye a crowne on mine innocent brow.”

All Bacon’s confessions, if true, prove him to have been a bastard, but this logical and inevitable conclusion he repeatedly denies. He claims his mother’s name, and for his father, a nobleman whose wife was living at the time of his bigamous marriage with Elizabeth. If the marriage was valid, why were Leicester and the Queen re-married at the house of Lord P., and in what year did the second ceremony take place? But although anti-Baconians maintain that Bacon was not a fool, and therefore could not have seriously advanced such claims; that if he had done so he would have made a more plausible story of his wrongs; that he was not a dunce, and therefore could not have written the “maudlin and illiterate drivel” attributed to him by Mrs. Gallup, it is still inconceivable that this cipher story is a gigantic fraud. Mr. Andrew Lang, who makes no doubt that Mrs. Gallup has honourably carried out her immense task of deciphering, has arrived at the conclusion that Bacon was obviously mad.

Bacon, the Author of all Elizabethan-Jacobean Literature